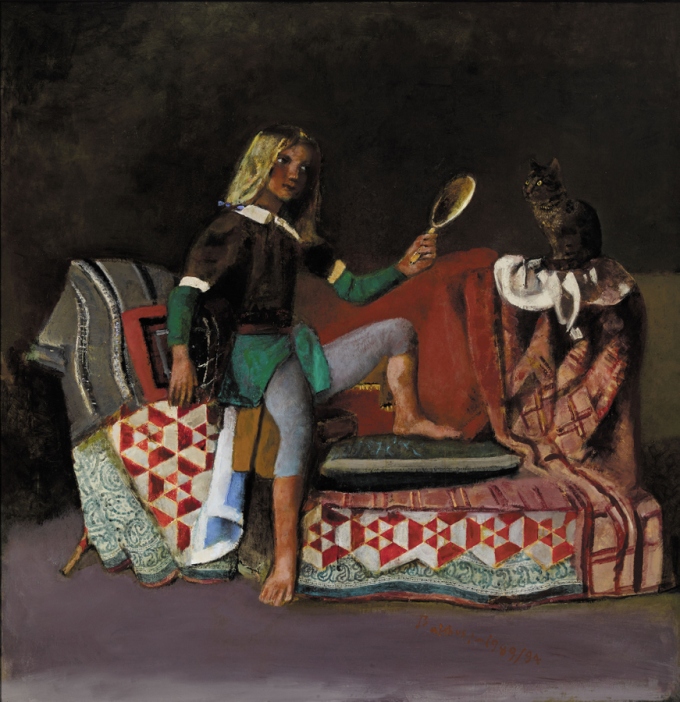

[Image: Balthus, Les Enfants Blanchard (1937), oil on canvas, 125 x 130 cm

Musée national Picasso-Paris, Donation by the heirs of Picasso, 1973/1978

© Balthus. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau]

The art of Balthus (1908-2001) is hard to place. It is not Surrealist, although it was linked to Surrealism. It is not realism, though it is derived from life. It is allied to tradition but is not traditional. It is not Modernist but could not have existed without Modernism. It is erotic but it is not erotica. To class it as Post-Modern would be completely erroneous. What is its lineage? It is European but – like its chameleon creator – it cannot be placed. The artist was born in France of Polish descent, growing up in France, Germany and Switzerland, later spending many years in Italy before moving to Switzerland with his Japanese wife. To think accurately about this European painter you need to know Japanese art and Persian miniatures; to discuss this friend and associate of Artaud, Giacometti, Picasso and Derain you will need to remember Chardin, Piero della Francesca, Georges de la Tour and Courbet. Through extended study you will come to recognise his models yet they are transformed through art into images distinctly different from life and artificial. If you expect anything to be straightforward about Balthus then you are misapprehending the art. No matter how complex, allusive and humorous the artist becomes, he is never less than absolutely serious.

Welcome to the world of Balthus.

The current exhibition Balthus (2 September 2018-1 January 2019, Fondation Beyeler, Basel; touring to Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid) forms a lean retrospective. (Reviewed here from the catalogue.) The exhibition consists of 40 oil paintings from all periods, starting when the artist was aged 20 and ending with his last completed painting, made when the artist was in his eighties. Considering the relatively small number of paintings, it is perhaps wise that drawings and watercolours have been excluded. The aim is establish a clear view of Balthus main subjects in a selection of representative paintings from the full span of his career.

All of Balthus’s subjects are included: portraits, conversation pieces, street scenes, landscapes and nudes. There is a hybrid work where a still-life is presented with a figure in the form of an incidental profile, not dissimilar to pictures by Bonnard of set tables. Paintings have been brought from around the world for this two venue tour.

Balthus’s first paintings were views of Paris, his home city. Place de l’Odéon, Quai Malaquais and Jardin de Luxembourg appear as they did in the 1920s. The youthful pictures are peopled by stock figures among sturdy trees and roughly painted architecture. They display a sure sense of colour and establish some of the staples of his later street scenes, though the skill and complexity are yet to manifest themselves fully.

The 1934 solo exhibition at Pierre Loeb’s Paris gallery established Balthus’s reputation as a singular – even wayward – painter of figures and assaulter of public morals. His most provocative early nudes – Alice dans le miroir (1933) and La leçon de guitare (1934), the latter of which was considered so sensational it was hidden behind a curtain at the Loeb gallery – have not travelled to Basel. However a number of works from that exhibition are here, including a scene from Wuthering Heights showing Cathy at her toilette.

[Image: Balthus, La Rue (1933), oil on canvas, 195 x 240 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Bequeathed by James Thrall Soby. © Balthus. Photo: © 2018. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence]

La Rue (1933) the large showstopper of the Paris exhibition has travelled to Switzerland from MoMA. The Parisian street is animated by figures who seem nearly wholly allegorical, lifted from book illustrations or old paintings, disconnected from each other. These atomised personages seem oblivious of each other and immersed in their own dreams, with the exception of the youth groping the girl. Whether or not is understands that she is being assaulted is unclear. Her face is impassive and her body language is stilted, not in motion (fighting or fleeing); it is hard to read her response. The youth was originally groping her crotch. The first owner demanded that Balthus alter La Rue to make it less indecorous, which he did. Balthus wavered on the subject of sexual provocativeness. He repainted a number of pictures to make them less overtly erotic. How much of that was genuinely held regret and how much was social positioning is unclear. In early years he shocked to gain attention and notoriety; in later years he curbed his earlier provocations in a bid for acceptance. That said, he did continue to paint nudes in his late years. It may be that he was simply swayed by the requests of his sitters and collectors to make their pictures more genteel. The famous narcissist and headstrong loner may have been less indomitable than he is sometimes presented.

In the late 1930s Balthus painted portraits. Sadly, the imposing and psychologically astute portraits of Derain and Miró have not travelled to Basel but the La Jupe blanche (1937) has. This full length portrait of Antoinette, Balthus’s first wife, shows the model in white clothing, rumpled creamy drapery clinging to the flesh and mimicking the pallor of her skin. The subject is a sensual and languorous object of desire while remaining detached and melancholic, sulky and bored; the subject is ultimately unreachably distant. That, of course, only makes the subject more alluring and memorable.

The late 1930s were Balthus’s Thérèse period, when Thérèse Blanchard modelled for 11 paintings, including a double-portrait with her brother. That painting was bought by Picasso and is loaned by Musée Picasso, Paris. Girls at the point of puberty or in adolescence henceforward became a constant subject. Girls at the threshold of becoming women present potent and changeable subjects because of the daily fluctuation and overlap between childhood and maturity, innocence and knowledge, timidity and adventurousness. In today’s society older girls are subjects bounded by taboos that go unspoken and sometimes unrecognised until they are transgressed.

Compare Balthus’s girls with depictions of girls of the same age by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805).

[Images: (left) Balthus, Thérèse (1938), oil on cardboard on wood, 100.3 x 81.3 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequeathed by Mr. and Mrs. Allan D. Emil, in honor of William S. Lieberman, 1987. © Balthus, Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence; (right) Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Broken Pitcher (1770)]

In Greuze’s tableaux the subjects are deflowered waifs and violated innocents. Although the purpose of Greuze was ostensibly moral and didactic, the subjects are salacious confections of wretchedness. The paintings are not so much moral warnings of the dangers of abuse as sadistic lingering upon the impact of that abuse. In contrast, Balthus’s subjects are mysterious beings, distant, playful and autonomous. Balthus’s paintings are as ambiguous and rich as people are, whereas Greuze’s paintings are shallow, one-note and fundamentally dishonest: ostensibly moral yet actually prurient. In Balthus’s paintings of adolescents we find an innovation in portraiture of the young that had not been seen since the portraits of children by Géricault in the 1810s.

In 1940, demobilised from the French army and living in the countryside, Balthus turned seriously to the subject of landscape. Two landscapes from the 1940s are included. Clarity and solidity are two of the primary attributes of Balthus’s landscapes. Balthus’s work became more mannered and artificial. When he was appointed director of the French Academy in Rome in 1961, Balthus became ever more engaged in ancient and non-Western art. He paid careful attention to every detail of the restoration of the academy’s home, the Renaissance Villa Medici. Balthus took pleasure in building surfaces in his paintings that evoke the thick encrusting of pigment on old plaster. References to Greek and Roman art abound. A visit to Japan is seen in several paintings and the relationship with his future second wife, Setsuko. The Basel exhibition includes the fragile and laboriously worked La Chambre turque (1965-6), which combines Persian and Japanese art in a painting of Setsuko. Experimentation with casein and tempera allowed Balthus to accentuate flatness and matte surfaces but at the expense of pliability. The increased rigidity led to thick and brittle paint surfaces which are fragile, especially on flexible canvas.

[Image: Balthus, Le Chat au miroir III (1989-94), Oil on canvas, 220 x 195 cm. Private collection, Asia. © Balthus]

Le Chat au miroir III (1989-94) shows a seated girl looking into a mirror, accompanied by a cat (a familiar motif for the artist). It is the artist’s last complete work. It is a summation of what came before but it is undercut by weaknesses in handling and conception. The extended gestation of the painting and frequent revisions are not so much evidence of a meditative patience but of a reluctance to finish, perhaps even of uncertainty. The artist may have felt the work was his last and was fearful of finishing and thereby cutting a cord to his working life and legacy. Too much rested on the painting and the desire to imbue it with a lifetime of knowledge and insight may have held the artist back. It might have been better to have worked on a number of minor pictures instead. It is some distance from his best work.

The catalogue is large format and profusely illustrated. The decision to place some illustrations as double-page spreads is regrettable. Illustrations should never be treated this way because it distorts the image by introducing a band of shadow and compression. Otherwise the production is good. Using strong (though not overpowering) colours for the margins of illustrations is effective. Brilliant white margins can clash with images, especially with richly coloured and tonally muted paintings such as Balthus’s.

Catalogue texts discuss works in the exhibition and illustrate others not included, including key works such as La leçon de guitare and the Miró portrait. One particularly useful text by Juan Ángel López-Manzanares deals with Balthus’s relationship with Antonin Artaud. The pair met in 1932 or 1933 and Balthus designed the sets for Les Cencis, the 1935 staging Artaud’s adaptation of Shelley’s verse drama. Balthus painted some portraits of actresses, including two of Iya Abdy. There are passing references to Balthus’s art as an expression Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty. The Theatre of Cruelty was the idea that naturalism and character had robbed Western theatre of the power of spectacle and mystery and that in order to restore the role of the sacred in theatre the dramatist and actors had to connect to the audience through transformational action and powerful emotion. The idea of Balthus’s early art running parallel to the Theatre of Cruelty – especially in the still-lifes of destroyed objects and the more aggressively erotic nudes – is a feasible thesis.

Raphaël Bouvier & Fondation Beyeler (eds.), Balthus, Fondation Beyeler/Hatje Cantz, 2018, paperback, 176pp, 120 illus., CHF62.50/€58.00, ISBN 978 3 7757 4445 4 (German and hardback versions available)

©2018 Alexander Adams

View my art and books at www.alexanderadams.art