Stimulating investment in pearl farming in ... - World Fish Center

Stimulating investment in pearl farming in ... - World Fish Center

Stimulating investment in pearl farming in ... - World Fish Center

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

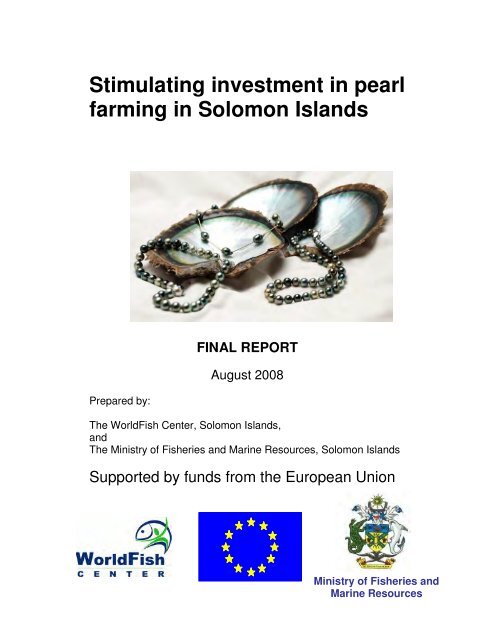

<strong>Stimulat<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>pearl</strong>farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon IslandsPrepared by:FINAL REPORTAugust 2008The <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong>, Solomon Islands,andThe M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Fish</strong>eries and Mar<strong>in</strong>e Resources, Solomon IslandsSupported by funds from the European UnionM<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Fish</strong>eries andMar<strong>in</strong>e Resources

CONTENTS1 THE PROJECT...............................................................................................12 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................22.1 Pearl farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Pacific.............................................................................22.2 Previous <strong>pearl</strong> oyster exploitation <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands...................................43 THE PEARL OYSTERS ................................................................................53.1 Suitability of coastal habitat <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands............................................53.2 Spat collection and growout............................................................................63.3 Water Temperature .........................................................................................83.4 White-lipped <strong>pearl</strong> oyster availability.............................................................83.5 The national white-lip survey .........................................................................83.6 Water quality.................................................................................................133.7 Natural disasters............................................................................................144 DOING BUSINESS IN SOLOMON ISLANDS..........................................154.1 Security of <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> ..................................................................................164.1.1 Governance and law......................................................................................164.1.2 Land and land lease issues ............................................................................174.1.3 Physical Security...........................................................................................184.1.4 Security of profits .........................................................................................184.2 Taxation and <strong>in</strong>centives ................................................................................194.2.1 Tax structure .................................................................................................194.2.2 Incentives ......................................................................................................194.3 Labour ...........................................................................................................204.4 Environmental impact assessment. ...............................................................215 POLICY, REGULATION AND MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES............215.1 Policy ...........................................................................................................225.2 Legislation.....................................................................................................235.3 Licenc<strong>in</strong>g.......................................................................................................256 INVESTOR VISITS .....................................................................................266.1 Investor Feedback .........................................................................................276.2 Commercialisation and F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g ................................................................286.3 Investor’s recommendations for next steps...................................................307 CONCLUSION.............................................................................................31

Appendix IAppendix IIAppendix IIIAppendix IVAppendix VAppendix VIPast research and development on black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters <strong>in</strong>Solomon Islands.Suitability of habitats <strong>in</strong> the Solomon Islands and other regions ofthe Pacific for growth of black-lip and silver-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters.Water temperature and cyclone frequency <strong>in</strong> the Solomon Islandsand other key regions of the Pacific: implications for <strong>pearl</strong>farm<strong>in</strong>g.Abundance, size structure and quality of silver-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters <strong>in</strong>Solomon Islands.Solomon Islands: the <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> climate for <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g.Pearl farm<strong>in</strong>g policy and management guidel<strong>in</strong>es.

1 The ProjectThe overall objective of the project is the reduction of poverty <strong>in</strong> rural areas of SolomonIslands through creation of livelihoods based on susta<strong>in</strong>able aquaculture. This fits with<strong>in</strong>the over-arch<strong>in</strong>g goals of the <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong> <strong>in</strong> the Pacific to reduce poverty andhunger <strong>in</strong> rural communities, and with the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Fish</strong>eries and Mar<strong>in</strong>e Resources(MFMR) to stimulate rural development and to develop aquaculture. It has beenrecognised that the nature of the <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry means that a high chance ofsuccess requires a long term <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> from an established <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g organisation.This project has been specifically designed to compile the elements of a pre-feasibilitystudy to provide offshore <strong>pearl</strong> companies with sufficient <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>in</strong>vestigate thepotential for long-term <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands.The overall output of the Project was <strong>in</strong>tended to be decisions by <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>gcompanies <strong>in</strong> the region to <strong>in</strong>vest, or not to <strong>in</strong>vest as the case may be, <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands,though these decisions are beyond the ability of project staff to <strong>in</strong>fluence. Throughout,staff have been admonished to provide unbiased, factual <strong>in</strong>formation free of weight<strong>in</strong>geither for or aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>. The direct outputs lead<strong>in</strong>g to the decisions concern<strong>in</strong>g<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> are:1. Documentation of past research and development on black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters <strong>in</strong>Solomon Islands likely to be of <strong>in</strong>terest to <strong>in</strong>vestors.2. A national survey of the location, abundance and quality of white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters<strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands.3. Analysis of climatic and habitat comparative advantages of Solomon Islands for<strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g.4. A summary of the <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> climate <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands.5. Policy guidel<strong>in</strong>es for susta<strong>in</strong>able <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> aquaculture and <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>gsupport<strong>in</strong>g small-holder community <strong>in</strong>volvement.6. High-level contacts with<strong>in</strong> the offshore <strong>pearl</strong> companies most likely to consider<strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands.7. Presentations to potential <strong>in</strong>vestors on the <strong>pearl</strong> oyster resources of SolomonIslands, results of research on culture methods and the advantages and risks of<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>, and policies for development of aquaculture and <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>Solomon Islands.8. Recommendations to government concern<strong>in</strong>g the licens<strong>in</strong>g conditions for <strong>pearl</strong>farm<strong>in</strong>g to provide opportunities for small-holders to supply large farms, and toensure that the <strong>in</strong>dustry operates <strong>in</strong> an environmentally susta<strong>in</strong>able way.9. A synthetic report cover<strong>in</strong>g all project activities.Each of these elements has been completed and this report represents the n<strong>in</strong>th of them.Rather than repeat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dividual consultants’ reports, itwill provide a broad narrative report synthesis<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation obta<strong>in</strong>ed from the1

various project elements to describe current conditions <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands with respect to<strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g. For ease of reference, the <strong>in</strong>dividual reports accompany thisdraft report as appendices. It is encourag<strong>in</strong>g to note that <strong>in</strong>terest from <strong>pearl</strong> farmers waspositive, with half of those contacted request<strong>in</strong>g more <strong>in</strong>formation. Ultimate success lies<strong>in</strong> land<strong>in</strong>g one <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong>vestor however, and it has emerged that there are otheractivities that might assist this process. At the end of this report we highlight the areas ofongo<strong>in</strong>g research that the <strong>in</strong>vestors consider will overcome the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g barriers to<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> Solomon Island <strong>pearl</strong>s.2 IntroductionSolomon Islands is a tropical, maritime country. Compris<strong>in</strong>g more than 900 islands andcover<strong>in</strong>g an area more than 900 x 250 km, the two parallel archipelagos that make up thegeographical sp<strong>in</strong>e of the country run from 6.5 o to 11 o S. Outly<strong>in</strong>g islands <strong>in</strong>crease thearea of the country still more. There are a myriad of undeveloped and unspoiled bays andsemi-enclosed lagoons rang<strong>in</strong>g from very small to the world’s largest double-reef lagoonsystem at Marovo Lagoon. One of the planet’s largest atolls, Ontong Java, is also found<strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands. For generations, Solomon Islanders have based their lives around thesea; today seafood still provides the bulk of dietary prote<strong>in</strong>, fish<strong>in</strong>g is part of a way of lifefor most rural Solomon Islanders and liv<strong>in</strong>g away from the coast is a rarity.As islanders’ lifestyles have undergone steady monetisation, the sea has cont<strong>in</strong>ued toprovide, with trochus shell, beche-de-mer, shark f<strong>in</strong> and fish constitut<strong>in</strong>g important cashcommodities. Mother of <strong>pearl</strong> (MOP), from black-, white- and brown-lipped <strong>pearl</strong>oysters has historically been an important cash commodity, although severe stockdepletion led to the imposition of an export ban s<strong>in</strong>ce 1994. With the hope that the banhas allowed stocks of <strong>pearl</strong> oysters to replenish and anecdotal evidence that this has beenthe case the Solomon Islands Government (SIG) has raised the question as to whether<strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g, which contributes to the economies of some other Pacific countries, couldbe effective <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands. This is a poor time to be enter<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>gcommunity, especially black <strong>pearl</strong>s. Pearls have become <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly competitive <strong>in</strong>recent years and scope for a new player <strong>in</strong> the market may be limited. However,competition has caused some operators to move offshore to cut labour and overheadcosts, to work with new stocks that may have marketable differences to traditional areasand escape the strict regulatory environment <strong>in</strong> some jurisdictions. Solomon Islandscerta<strong>in</strong>ly has the right conditions for growth of <strong>pearl</strong> oysters and plenty of space for farmestablishment, but crucially it may offer advantages <strong>in</strong> these economically importantareas.2.1 Pearl farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the PacificSeveral species of <strong>pearl</strong> oyster (family Pteriidae) occur <strong>in</strong> the Pacific Islands region,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Solomon Islands. Two, the black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster, P. margaritifera, and the2

white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster 1 , P<strong>in</strong>ctada maxima, are widely used <strong>in</strong> commercial production offarmed <strong>pearl</strong>s, and both of these occur naturally <strong>in</strong> Solmon Islands. P margaritifera is thesmaller of the two species, and is found throughout the Pacific Islands region, as well as<strong>in</strong> the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. P maxima has a more limited distribution, and is onlyfound naturally <strong>in</strong> the western Pacific <strong>in</strong> high-island countries west of Fiji, althoughattempts have been made to <strong>in</strong>troduce it to Palau, Kiribati, Tonga and other countries.Commercial farm<strong>in</strong>g of white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> shell orig<strong>in</strong>ally developed on the northern andwestern coasts of Australia. In recent years some Australian operators have movedoffshore, as a result of which new farm<strong>in</strong>g operations have spread to Indonesia Vietnam,Cambodia, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es and Myanmar. Indonesia has now overtaken Australia as theworld’s largest producer of P. maxima <strong>pearl</strong>s <strong>in</strong> terms of volume, although not yet <strong>in</strong>terms of value. A s<strong>in</strong>gle white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> farm has been operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Papua New Gu<strong>in</strong>eas<strong>in</strong>ce about 1995, but there are no others <strong>in</strong> the Pacific Islands region. Pearls from whitelip<strong>pearl</strong> oysters are generally more valuable than those from black-lip because of theirgold-to-white coloration and larger sizes.Pearl farm<strong>in</strong>g us<strong>in</strong>g the black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> shell has been the doma<strong>in</strong> of the Pacific Islandsregion <strong>in</strong> the central Pacific. It has developed primarily <strong>in</strong> French Polynesia and CookIslands, of which French Polynesia is by far the most prom<strong>in</strong>ent. In recent years black-lip<strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g has spread to Melanesia and Micronesia, particularly to Fiji, wherespectacular and unusually coloured <strong>pearl</strong>s are be<strong>in</strong>g produced. Pearl farm<strong>in</strong>g wentthrough a 25-year development phase <strong>in</strong> French Polynesia, and cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be thebiggest employer and export earner for the country. However the <strong>in</strong>dustry has decl<strong>in</strong>edsignificantly <strong>in</strong> recent years, ma<strong>in</strong>ly due to problems of overproduction and poor <strong>pearl</strong>quality (discussed more later). In 1998 French Polynesia produced around 5 tonnes of<strong>pearl</strong>s worth over US$ 150 million; <strong>in</strong> 2002, it exported over 11 tonnes, worth about thesame amount. Average <strong>pearl</strong> prices have fallen from around US$ 35/ gramme to aboutUS$ 14/ gramme <strong>in</strong> the past ten years.Pearl farm<strong>in</strong>g has contributed enormously to the French Polynesian economy, both due tothe revenues it generates, and because it can be carried out <strong>in</strong> remote areas and thuscontribute to rural earn<strong>in</strong>gs and livelihoods. In its heyday the development of the <strong>pearl</strong><strong>in</strong>dustry was accompanied by a reversal of the trend towards urban drift, with manyresidents of the capital, Tahiti, return<strong>in</strong>g to their orig<strong>in</strong>al homes <strong>in</strong> the outer islands totake up <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g. As a result of fall<strong>in</strong>g <strong>pearl</strong> values, however, the social benefitsbe<strong>in</strong>g derived from the <strong>in</strong>dustry are also <strong>in</strong> decl<strong>in</strong>e. Between 1990 and 2008 the numberof <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g concessions fell from 2,700 to around 700, with larger producers buy<strong>in</strong>gout many of the smaller family farms dur<strong>in</strong>g that period. Around 7,000 people are nowthought to be employed <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>dustry, down from more than three times that figure 15years ago. There are new signs of population drift from outer islands to the capital andother urban centres, and concerns over the social problems this may engender.1 P. maxima is commonly referred to as white-lip, gold-lip and silver-lip. It is not known for certa<strong>in</strong>whether only one or both these varieties occurs <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands. The term white-lip is used here to<strong>in</strong>clude both varieties.3

PNGSolomon IsPNGCook IsVanuatuFijiFr. PolynFigure 1. Google Earth image of the South Pacific show<strong>in</strong>g <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g regionsreferred to <strong>in</strong> this document. Australian sites from the NW coast, through Torres Straightto southern Queensland are approximated.2.2 Previous <strong>pearl</strong> oyster exploitation <strong>in</strong> Solomon IslandsPearl farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands is not a new idea (see Appendix I). Co<strong>in</strong>cident withthe first modern pulse of MOP harvest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> 1968-1972, attempts were made to establisha <strong>pearl</strong> culture <strong>in</strong>dustry, but this was not successful and closed with the commercial MOPfishery when stocks were so depleted that fish<strong>in</strong>g became uneconomic. A second pulseof MOP harvest<strong>in</strong>g occurred between 1987 and 1994, when an export ban came on <strong>in</strong>response to stock depletion. Shortly after the ban, an experimental black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> farmwas set up near Gizo <strong>in</strong> Western Prov<strong>in</strong>ce. By 2000 <strong>pearl</strong>s were produced and sold, butthe experimental farm did not attract commercial <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> and ceased to produce <strong>pearl</strong>s<strong>in</strong> 2003 when research funds ran out.4

Pearl<strong>in</strong>g is not new to Solomon Is. In 2000-2003 black <strong>pearl</strong>s were successfully producedat an experimental farm <strong>in</strong> Western Prov<strong>in</strong>ce.The period 2000-2003 was a poor time to be seek<strong>in</strong>g <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands.The country was wracked by civil strife from 1999 to 2003, when an Australian-led<strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>in</strong>tervention force, the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands(RAMSI) arrived. With order restored and the economy grow<strong>in</strong>g, the government isattempt<strong>in</strong>g to promote overseas <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>, particularly <strong>in</strong> the rural areas. As part of thisprocess, it has been assisted by the European Union’s STABEX fund to produce acomprehensive portfolio of <strong>in</strong>formation to dissem<strong>in</strong>ate to companies and <strong>in</strong>vestorspotentially <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands.3 The <strong>pearl</strong> oysters3.1 Suitability of coastal habitat <strong>in</strong> Solomon IslandsBoth species of <strong>pearl</strong> oyster that are currently used <strong>in</strong> the Pacific for cultivation of <strong>pearl</strong>s,P<strong>in</strong>ctada margaritifera (the black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster) and P. maxima (the white or gold-lip<strong>pearl</strong> oyster) are native to Solomon Islands (see appendices II and IV). Both have nationwidedistributions, although the preferred habitat for adult white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters is morepatchy than that of black-lip. Reef structure <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands is ak<strong>in</strong> to that <strong>in</strong> otherMelanesian countries (Papua New Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, Fiji, Vanuatu) with reefs fr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g islands,where they can form complex lagoon structures, but with atolls rare (e.g. Figure 2).Black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters are usually associated with hard substrata <strong>in</strong> the shallower parts ofsuch reefs, while adult white-lips tend to occur more <strong>in</strong> fast flow<strong>in</strong>g channels amongstislands and reefs than on the reefs themselves.5

Figure 2. Typical coastal habitat for much of Solomon Islands. Fr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g reefs, a mix ofhigh and low-ly<strong>in</strong>g islands and freely exchang<strong>in</strong>g lagoon structures prevail. Closed orsemi-closed atolls are rare.The prevalence of fr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g reefs rather than atolls contrasts with the situation <strong>in</strong> the CookIslands and French Polynesia, where black <strong>pearl</strong> farms are typically based <strong>in</strong> atolls whereblack-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster reach their maximum abundance. Growth rates of oysters with<strong>in</strong>these nutrient-poor lagoons are, however, less rapid than outside of the lagoons. Goodresults of grow-out of black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster <strong>in</strong> Fiji and Solomon Islands confirm that,provided the requirement for high-quality water is met, fr<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g reef lagoons andembayments can be suitable sites for cultivat<strong>in</strong>g black <strong>pearl</strong>s. We note that SolomonIslands has one of the world’s largest atolls, Ontong Java, at 5 o S latitude, but there is no<strong>in</strong>formation on the status of <strong>pearl</strong> oysters there; it may be too far north and too warm forblack-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster culture.3.2 Spat collection and growoutPrevious research programmes target<strong>in</strong>g <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g have yielded a good deal of<strong>in</strong>formation on the black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands. As this research wastargeted at modify<strong>in</strong>g techniques <strong>in</strong> use <strong>in</strong> French Polynesia for Solomon Islands, thedifferences between the countries were <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>in</strong> detail. A feature of the atolllagoons where <strong>pearl</strong> cultivation has been developed <strong>in</strong> Polynesia is that they facilitatecollection of spat by trapp<strong>in</strong>g eggs produced with<strong>in</strong> the lagoon. Spat is a key element ofblack-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster cultivation and spat collection <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands is more difficultthan <strong>in</strong> these Polynesian farms due to the more open reef structures and greatermovement of water. However, research by the <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong> has shown that spat can6

e successfully harvested from close to Solomon Island reefs throughout the country.Experimental spat collections have been made from Guadalcanal to Shortland Islands andmost regions had broadly similar spatfalls. Of the areas where high collections are mostfrequent, Western Prov<strong>in</strong>ce (see Figure 3 for locations) stands out, though even here theyield per spat collector can be low (an average of 1-12 per collector deployment) and isvariable between locations and years.ChoiseulMann<strong>in</strong>g StraightShortlandIslandsKiaWagh<strong>in</strong>aWesternSanta IsabelGizoNoroMarovoLagoonRussellIsalndslHoniaraGuadalcanalMalaita100 kmMakiraFigure 3. Map of Solomon Islands marked with prov<strong>in</strong>ces and ma<strong>in</strong> locations referred to<strong>in</strong> the text. The scale bar represents 100 km.A significant issue <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands has proved to be the high predation on young spat,which led the experimental <strong>pearl</strong> farm to amend the traditional protocols for spatcollection and grow-out. Rather than leav<strong>in</strong>g spat on collectors until they reach a sizelarge enough for hang<strong>in</strong>g from grow-out l<strong>in</strong>e, as d<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> French Polynesia, spat wereharvested from collectors at a small size (~10 mm) and an <strong>in</strong>termediate grow-out phasewas <strong>in</strong>troduced until they reached the size for transfer to hang<strong>in</strong>g culture. The labour costof this extra operation may be offset by the low labour costs <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands (US$ 5-7per day for semi-skilled workers compared to US$ 50 per day <strong>in</strong> Tahiti – see latersections). Once established, however, grow-out of oysters can be rapid at SolomonIslands, with spat able to reach 100-120 mm <strong>in</strong> one year. This is six months faster than istypical of atoll farms <strong>in</strong> Cook Islands. Prepar<strong>in</strong>g the report summaris<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formationon black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters allowed Patrick Mesia from the Aquaculture section of MFMR7

to work alongside <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> science staff and ga<strong>in</strong> experience and confidence withcontribut<strong>in</strong>g to written reports.3.3 Water TemperatureSolomon Islands’ proximity to the equator and consistently high seawater temperatures(Appendix III) may <strong>in</strong> part be the cause of the rapid growth of black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster.Figure 4 shows that Solomon Islands is the most northerly site <strong>in</strong> the region to growblack-lip <strong>pearl</strong>s, and that temperatures tend to be slightly higher than other black <strong>pearl</strong>areas (Fiji, Cook Islands and French Polynesia). The white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster, which tendsto prefer warmer water than the black-lip, may also be an appropriate species choice forthis location.Temperature ranges for Solomon Islands and established <strong>pearl</strong><strong>in</strong>g countries are shown <strong>in</strong>Table 1. The warm, stable temperatures of Solomon Islands are similar to white-lipfarm<strong>in</strong>g regions at Northern Queensland/Torres Straight and PNG, and only slightlywarmer than black-lip farms at Cook Islands. Environmentally, Solomon Islands shouldbe suited to the culture of both black and white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters.Table 1. Approximate temperatures of Solomon Island waters and for <strong>pearl</strong>-produc<strong>in</strong>gregions. Where a range of values is given data are available across a latitud<strong>in</strong>al range.Location M<strong>in</strong>imum Maximum RangeSolomon Is 27-28 29-30 2Northern Cook Is 27 29 2Fiji 24-27 28-29 2-4PNG 26-28 30 2-4French Polynesia 24-27 27-29 2-3NW Australia 24-25 28-30 4-5Torres Straight 26 29 3Vanuatu 24-27 28-30 3-43.4 White-lipped <strong>pearl</strong> oyster availabilityUnlike black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster, white-lip is not commercially taken as spat. Instead amixture of harvested young adult shell and hatchery stock are used. Anecdotal reports ofhealthy populations of gold-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters at sites around Solomon Islands needed to beassessed and as part of this project a comprehensive survey was planned to assess stocks.3.5 The national white-lip surveyThe national white-lip survey was undertaken jo<strong>in</strong>tly by <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong> and MFMR(see Appendix IV) and had four elements:8

1. a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary survey of villages previously engaged <strong>in</strong> the MOP trade to obta<strong>in</strong>from local fishers <strong>in</strong>formation on the current distribution of gold-lip and to obta<strong>in</strong>permission to work <strong>in</strong> customary waters2. a tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g phase for local staff <strong>in</strong> advanced div<strong>in</strong>g techniques, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g use ofHookah gear and <strong>in</strong> Survey techniques3. the survey itself4. analysis and report<strong>in</strong>g of the survey data, which <strong>in</strong>cluded a tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g element forMFMR staffFigure 4. Locations of black- and white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> farms <strong>in</strong> the South Pacificsuperimposed on summer and w<strong>in</strong>ter temperatures derived from satellite imagery.Solomon Islands is <strong>in</strong>dicated by the blue circle.The prelim<strong>in</strong>ary survey was an essential part of the study. Locations (Figure 5) wereselected on the basis of areas spread across the country but each with a record ofsubstantial harvests of MOP <strong>in</strong> the data held by the MFMR. All locations were visited at9

least two weeks before the ma<strong>in</strong> survey took place. At each, village meet<strong>in</strong>gs were heldto <strong>in</strong>form people of the study, to ask permission to work <strong>in</strong> customary waters and toconduct <strong>in</strong>terviews regard<strong>in</strong>g historical distribution of <strong>pearl</strong> oysters, likely currentdistribution (and, hence prospective sampl<strong>in</strong>g sites) and occurrence of any recent orongo<strong>in</strong>g exploitation. Dur<strong>in</strong>g each <strong>in</strong>terview, the study team sought to have at least oneperson present who could speak/translate between Pidg<strong>in</strong> and the local dialect and onescientist from the survey team who was fluent <strong>in</strong> Pidg<strong>in</strong> and English. A questionnairewas used to structure the <strong>in</strong>terviews and a m<strong>in</strong>imum of five local people who expressedpersonal experience of <strong>pearl</strong> oyster fish<strong>in</strong>g were <strong>in</strong>terviewed. At each location, threesites were identified on the basis of fisher feedback that were most likely to yield highnumbers of shell.Wagh<strong>in</strong>aKiaTel<strong>in</strong>aMboliSandlfyMbiliMaramaskeMarauFigure 5. Sites selected for white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster survey.Communities at all eight locations were easily able to identify three or more sites wheremany oysters should be found. As will be seen later when we report results, not allcommunities were accurate <strong>in</strong> this regard. The replies to questionnaires, however, showedthat even at the height of the mother-of-<strong>pearl</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry, the <strong>pearl</strong> oyster was a substantialcontribution to community <strong>in</strong>come only at Kia and Wagh<strong>in</strong>a. These two locations10

consistently emerged as the centres for this species, a f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that confirms previousreports on the MOP <strong>in</strong>dustry.The tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g element of the survey <strong>in</strong>volved formal advanced SCUBA div<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g,result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> awards of recognised <strong>in</strong>dustry (PADI) qualifications, <strong>in</strong>formal tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> theuse of Hookah (surface supplied) div<strong>in</strong>g equipment and <strong>in</strong>formal tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the surveytechniques to be applied. Table 1 lists the national staff <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> underwater surveyand <strong>in</strong>dicates the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g given, and copies of certificates are available from <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong><strong>Center</strong>, Solomon Islands.The survey itself was <strong>in</strong> two phases. The first phase used the live-aboard charter vesselMarl<strong>in</strong> I, chartered from Papua New Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, and covered the eastern sites, fromMaramsike on Malaita through to Tel<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> New Georgia. The western sites, Kia andWagh<strong>in</strong>a, were undertaken by small boat from the <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> field station at Nusa Tupe,near Gizo. Initially it was <strong>in</strong>tended to use the Marl<strong>in</strong> I for all sites, but this plan had to bemodified as the survey was <strong>in</strong>terrupted by the tsunami that hit Western Prov<strong>in</strong>ce on 2 ndApril. The tsunami hit just as the first tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was be<strong>in</strong>g undertaken <strong>in</strong> Marovo Lagoonand, because many participants lived <strong>in</strong> Gizo, this had to be abandoned. Instead, after aperiod of assist<strong>in</strong>g with the aid effort follow<strong>in</strong>g the tsunami, the survey was resumed, butavoided the most affects areas. The charter period ran out before all sites could becompleted, and f<strong>in</strong>ish<strong>in</strong>g the survey by small open boat had to await the relatively calmweather of October.Table 1. National staff receiv<strong>in</strong>g dive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g through the projectName Organisation Dive tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Survey tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gFrancis Kera MFMR Advanced Open Water April 2007Jon Leqata MFMR Advanced Open Water April 2007Alex Meloty MFMR Advanced Open Water April 2007Patrick Mesia MFMR Advanced Open Water April 2007Ronnie Posada WFC Advanced Open Water April 2007Peter Rex MFMR Advanced Open Water April 2007Stephen Sibiti WFC Rescue diver October 2007Mason Tauku WFC Rescue diver April 2007Ambo Tewaki WFC Rescue diver October 2007Regon Warren WFC Rescue diver April 2007The survey protocol that the national staff learned <strong>in</strong>volved towed dives at each of thethree sites at each of the eight locations. Apparatus was constructed locally to tow twodivers beh<strong>in</strong>d weights lowered from the ends of a boom rigged across a 6 m alum<strong>in</strong>iumboat, ensur<strong>in</strong>g that they were able to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> close contact with the sea bed (essentialfor spott<strong>in</strong>g the cryptic oysters). At each site, the divers collected all the <strong>pearl</strong> oystersthey observed along four randomly-positioned 4 m wide transects. All were measured,and up to ten at each site were sacrificed to determ<strong>in</strong>e the nacre colour. Also recordedwere the latitude and longitude at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and end of each transect, time and11

duration of the dive, maximum bottom depth and the type of substrata found along eachtransect. Position and depth were taken from a Humm<strong>in</strong>gbird 737 comb<strong>in</strong>ationGPS/Echo sounder and transect lengths were derived from straight l<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong>terpolationsbetween start and f<strong>in</strong>ish po<strong>in</strong>ts. All national staff were tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> all aspects of the surveytechnique and all had an opportunity to experience each role <strong>in</strong> the team. For many, thiswas their first opportunity to work with GPS and echo sound<strong>in</strong>g equipment as well as thediv<strong>in</strong>g methods <strong>in</strong>volved.Divers were not able to access safely depths beyond 35 m. For observations down to 60m a towed underwater camera was used, which recorded onto a Sony DVD recorder.Video surveys were made at four of the sites, where substrate and conditions permitted.Image quality of the camera was less than ideal, but while exact counts of organismswere difficult it was possible to ascerta<strong>in</strong> whether or not dense populations of <strong>pearl</strong> oysterwere present beyond div<strong>in</strong>g depth.Once the surveys were completed, report<strong>in</strong>g began. Two tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g elements were<strong>in</strong>cluded. Jon Leqata was <strong>in</strong>volved with external consultants <strong>in</strong> preparation of the reporton the stock assessment and a draft manuscript for submission to the <strong>in</strong>ternational journalBiological Conservation. Copies of that manuscript are available from <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong><strong>Center</strong>, Solomon Islands. In addition Dr Hawes from <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong> led a 2-dayworkshop for all staff from the Research and Aquaculture sections of MFMR on dataanalysis, us<strong>in</strong>g the survey data as an example.The results of the survey were disappo<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g. A total of 117 P. maxima were found, butonly 33 of the 96 transects yielded any oysters. The mean (± standard error.) density ofoysters per 400m 2 transect ranged from 1.23 ± 0.38 at Wagh<strong>in</strong>a, 1.03 ± 0.27 at Kia and0.66 ± 0.27 at Mboli Passage to

The conclusion of the stock assessment was that the population was <strong>in</strong>sufficient to allowany quota to be allocated for <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g at the present time, and that any <strong>in</strong>dustryestablish<strong>in</strong>g here would need to be based around hatchery reared stock. We note that anyfollow-up work to this project might address the question of whether such a hatcherycould reasonably be established <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands, and look <strong>in</strong> more detail at the areasaround Kia and Wagh<strong>in</strong>a to obta<strong>in</strong> a more robust estimate of stock status; we believe thatthis would greatly enhance the possibility of the current research yield<strong>in</strong>g success for therural peoples of Solomon Islands. This f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g does not prevent establishment of a <strong>pearl</strong><strong>in</strong>dustry. Hatchery reared shell are <strong>in</strong> use <strong>in</strong> several other areas where wild stocks aresmall, and two of the <strong>in</strong>vestors to visit Solomon Islands make extensive use of hatcheryshell <strong>in</strong> their other operations.Figure 6. Examples of white (left), gold (centre) and off-white (right) shell taken fromKia and Wagh<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> the Mann<strong>in</strong>g Straight region.3.6 Water qualityWater quality requirements differ between black- and white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster. Black-lip<strong>pearl</strong> oyster are usually grown <strong>in</strong> clear, oceanic water with no effect from land run-off.White-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster appear more tolerant of moderate turbidity and sal<strong>in</strong>ity fluctuationsthan black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster. In Western Australia some farms are <strong>in</strong> bays with substantialfreshwater runoff, others <strong>in</strong> bays with little and experimental comparisons between turbidand clear embayments. Experimental comparisons have shown no significant difference<strong>in</strong> growth rate. The steep topography of some Solomon Island islands and the frequentheavy ra<strong>in</strong>fall that these attract means that some coastal lagoons (especially thoseimpacted by poorly managed forestry developments) are affected by turbidity andfreshwater runoff. Such systems may be better suited to culture of white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysterthan black. However, many other island-lagoon systems are smaller and low-ly<strong>in</strong>g and donot suffer from run-off.13

3.7 Natural disastersEnvironmental risks come <strong>in</strong> many forms, from earthquake, tsumani, cyclone, through todisease and long-term sea level rise. Most of these are poorly predictable or equallylikely (or unlikely) over wide geographic scales. Of the few “extreme event”-relatedenvironmental risks that are frequent enough to be quantifiable, cyclones and their relatedphenomena can be devastat<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>pearl</strong> farms (see Appendix III). Analysis of theprevalence of cyclones at Solomon Islands (Figure 7) suggests that its risk profile issimilar to Tahiti and places it between PNG, where cyclones are extremely unlikely andNorthern Cook Islands, where one cyclone has passed with<strong>in</strong> 50 km <strong>in</strong> the period1969/70 to 2004/05. One cyclone has passed a similar distance from Honiara over thatperiod, though none has passed though or affected the Western Prov<strong>in</strong>ce. Cyclones aremuch more likely to pass close to Fiji, Vanuatu and Australia. Cyclones can be seen as am<strong>in</strong>or risk for <strong>pearl</strong> farms <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands, particularly if placed <strong>in</strong> they are located <strong>in</strong>the northern part of the country.Average Annual number of tropical cyclonesFigure 7. Approximate positions of exist<strong>in</strong>g black and white <strong>pearl</strong> farms and SolomonIslands (blue circle) superimposed on the average tropical cyclone frequency for thesouthwest Pacific.14

4 Do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> Solomon IslandsEnvironmental and ecological factors are a small part of the decision mak<strong>in</strong>g that needsto accompany <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands. Perceived problems over security,stability, corruption and government <strong>in</strong>tervention may sometimes deter foreign<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> but, if due caution is exercised, <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands is as secure as<strong>in</strong> any Pacific islands country (see Appendix V). This is a particularly acute area for <strong>pearl</strong>farm<strong>in</strong>g, as <strong>in</strong> most cases little return is made for at least six years and net profit may taketen years or more to achieve. Long term stability is essential. An important prelim<strong>in</strong>aryto assess<strong>in</strong>g what <strong>in</strong>formation needs to be given to potential <strong>in</strong>vestors was to attempt todeterm<strong>in</strong>e which issues would be <strong>in</strong> their m<strong>in</strong>ds when consider<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> SolomonIslands. A workshop was held for MFMR staff and technical assistants which addressedthis question circuitously by consider<strong>in</strong>g the advantages and disadvantages of SolomonIslands – and how disadvantages can be mitigated. Outcomes of this workshop weregrouped under two questions, many of which have been covered already <strong>in</strong> this report,but others of which have not. The author’s selection of key issues to address <strong>in</strong> therema<strong>in</strong>der of this report, which deals with economic, cultural and structural issues areitalicised.Why grow <strong>pearl</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands?• Both black-lip and white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters are native to Solomon Islands• A national ban on harvest<strong>in</strong>g both species exists with no <strong>in</strong>tention to resc<strong>in</strong>d theban• There is a 10 year history of collection of spat of black-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oyster andproduction of <strong>pearl</strong>s has been demonstrated• Pearl oysters grow fast <strong>in</strong> the warm, well-flushed coastal lagoons of SolomonIslands• The environment <strong>in</strong>cludes very many more-or-less sheltered coastal lagoonswhere suitable growth conditions may be found for either or both species• Cyclones are very rare• Labour is cheap, <strong>in</strong>come opportunities <strong>in</strong> rural areas are rare and many ruralcommunities are eager to negotiate use of land and waters• Alternatively there is government land where leaseholds are secure• The government is will<strong>in</strong>g to negotiate <strong>in</strong>centives to committed <strong>in</strong>vestors• There are no other <strong>pearl</strong> operations <strong>in</strong> the country and a unique brand<strong>in</strong>g ispossible• Solomon Islands are less than three hours by air from Brisbane, has an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gexpatriate community and tourism is expected to <strong>in</strong>crease• The M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Fish</strong>eries and Mar<strong>in</strong>e Resources is eager to facilitate such an<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> and has committed to assist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vestors through the early phases ofany such project• Options exist for a phased entry, with jo<strong>in</strong>t public-private research towardscommercialisation of Solomon Island <strong>pearl</strong>s possible us<strong>in</strong>g exist<strong>in</strong>g hatchery andfield facilities15

• Legislative review is underway to provide a sound basis for commercialaquaculture.Why not grow <strong>pearl</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands?• Pearls are a competitive product and the pay-back time on <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> is likely tobe many years• Black-lip spat settlement is variable between years and sites and not alwaysstrong. Extensive spat collection sites and/or hatchery backup may be required• Populations of white-lip <strong>pearl</strong> oysters are currently <strong>in</strong>sufficient to allowcommercially viable quotas of wild stock. A hatchery may be required• Land tenure <strong>in</strong> some parts of the Solomon Islands is confused and unreliable.Careful site selection and negotiation, with the support of the M<strong>in</strong>istry will berequired• Investors will need to set up and ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> harmonious relationships with localcommunities• In-country markets are currently weak but grow<strong>in</strong>g• The country has a record of political <strong>in</strong>stability, although s<strong>in</strong>ce the arrival ofRAMSI <strong>in</strong> July 2003 this has not been evident• National and (especially) prov<strong>in</strong>cial authorities have limited capacity to developand enforce regulations and agreements. Careful negotiation and support of theM<strong>in</strong>istry will be required• There is no strong history of aquaculture with<strong>in</strong> the country; the only currentaquaculture be<strong>in</strong>g small scale culture of seaweed, giant clams and corals.These issues have been grouped and addressed under three subhead<strong>in</strong>gs: Security of <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> (government stability, security of tenure, physical security) Taxation and <strong>in</strong>centives Labour4.1 Security of <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>4.1.1 Governance and lawBoth National and Prov<strong>in</strong>cial Governments <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands prioritise decentralised<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>, creation of rural jobs and <strong>in</strong>come opportunities and <strong>in</strong>creased exportearn<strong>in</strong>gs; <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g scores well all round and government <strong>in</strong>terference <strong>in</strong> the<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> process is unlikely. Solomon Islands government is not based around politicalparties, but around loose and dynamic group<strong>in</strong>gs of <strong>in</strong>dependent politicians. While thereis much news of “political <strong>in</strong>stability” <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands, this largely concerns whoshould be Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister and thus <strong>in</strong> charge of patronage, while external relations withCh<strong>in</strong>a/Taiwan and Australia are also a matter of debate. There are few discernibledifferences <strong>in</strong> policy among the various group<strong>in</strong>gs and major shifts relat<strong>in</strong>g to foreign<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> seem unlikely with chang<strong>in</strong>g governments.Establish<strong>in</strong>g <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands has become simpler <strong>in</strong> recent years. Undercurrent regulations, a company to be set up to farm <strong>pearl</strong>s would need first to apply under16

the Foreign Investment Act. As <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g is not listed as a restricted or prohibitedactivity, a certificate of registration should be issued with<strong>in</strong> five days. More detailedissues may then be addressed. This process is under judicial review of matters of law andthe constitutional <strong>in</strong>dependence of the judiciary generally renders it free of political<strong>in</strong>terference. The legal system is considered slow but fair and recently a change ofgovernment was precipitated by a Prime M<strong>in</strong>ister’s fill<strong>in</strong>g of the Attorney General’sposition with a close personal friend.Unlike the judiciary, the Public Service has suffered from direct political <strong>in</strong>terference andhas been weakened by corruption <strong>in</strong> many departments. The departments with which an<strong>in</strong>vestor would ma<strong>in</strong>ly be deal<strong>in</strong>g (<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> registration, taxation, employment,immigration, lands, fisheries, prov<strong>in</strong>cial government) are all ostensibly aim<strong>in</strong>g topromote and assist legitimate <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>, but they vary <strong>in</strong> experience, effectiveness andspeed of do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Investors should ensure that documents are carefully preparedand presented, and sufficient time allowed for process<strong>in</strong>g and discussion of anydifficulties with relevant officials. Any suggestion that additional unofficial paymentswould facilitate process<strong>in</strong>g should be rejected.4.1.2 Land and land lease issuesA key issue for <strong>in</strong>vestors will be secur<strong>in</strong>g long-term leasehold of suitable premises. Likemuch of Melanesia, land (and associated reefs and coastal waters) <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands isheld either under customary tenure (90%) or under a system of registration of land (10%).Registered land has gone through a process of title and rights <strong>in</strong>vestigation before be<strong>in</strong>gregistered, and the <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> registered land recorded on the Land Register are thesubject of <strong>in</strong>demnity by the government. Leases on such lands are secure. Customaryland is more problematic. Def<strong>in</strong>itions of customary land rights and boundaries arecomplex and often disputed, more so as customary authority and leadership have brokendown <strong>in</strong> many areas under pressure from monetisation, education and the physical andf<strong>in</strong>ancial stresses of commercial logg<strong>in</strong>g. The barriers that customary tenure erect aga<strong>in</strong>st<strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> are appreciated and mach<strong>in</strong>ery does exist to convert customary tenure toregistered land, though this requires extensive <strong>in</strong>vestigations of traditional use rights andcommunity history. If attempt<strong>in</strong>g to acquire a registered <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> customary land, an<strong>in</strong>vestor would need to be assured of local acceptance of the proposed <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> throughextensive <strong>in</strong>teractions with local leaders and communities before <strong>in</strong>itiat<strong>in</strong>g theregistration process.In short, commercial <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> on unregistered land by a foreign company would berisky and is not recommended. Conversion of customary land to registered status iscomplex and slow. Lease or purchase of an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> land that is already registered, andhas been or is now <strong>in</strong> use <strong>in</strong> some form of economic activity, is advised as the bestsolution to acquir<strong>in</strong>g premises. Such lands exist <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g locations, with thoseperhaps most suitable to <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g (based on habitat quality) <strong>in</strong> italics:− Shortlands (Ballalae airstrip), Gilbertese resettlement, close to Bouga<strong>in</strong>ville− Wagh<strong>in</strong>a, Gilbertese resettlement, Kagau (airstrip)17

− Mann<strong>in</strong>g Strait islands− Suavanao (airstrip)− NW Isabel coastl<strong>in</strong>e, Allardyce Harbour− Reef islands southeast of Gizo, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Nusa Ttupe (Gizo airport,<strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> hatchery), tourist resorts and Gilbertese resettlement− South Vona Vona lagoon (Munda airport)− NW Marovo lagoon reef islands (Ramata) (airstrip)− SW Marovo lagoon (Uepi, Seghe) (Seghe airstrip)− Russell Islands (Yand<strong>in</strong>a airstrip)− Sandfly Island and passage (Maravari)− Marau Sound, East Guadalcanal (airstrip) (shell jewellery, coral culture)(Tavanipupu resort)− East MakiraRegistered leasehold <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> land, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g land below the highwater mark, that isadjacent areas of lagoon, shore and coral reef, will be legally secure provided theappropriate procedures under the Land and Titles Act have been followed. However, it isalways the case that good relations with local communities are crucial to successfuloperations <strong>in</strong> rural areas. It would be impracticable to make and operate any agriculturalor maricultural <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> a rural sett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a hostile social environment. It will benecessary to make sure that local communities know and understand what is proposed,that the operation is designed to provide as much participation for local people as isreasonable and practicable, bus<strong>in</strong>ess transactions with them are transparent, on fair termsas to prices and quality and are properly recorded.4.1.3 Physical SecurityIn rural locations <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands physical security depends on a comb<strong>in</strong>ation offactors. Regular patroll<strong>in</strong>g by the police is simply not available. An <strong>in</strong>vestor with portableassets and stock to protect needs to take clear and non-provocative precautions aga<strong>in</strong>sttheft that are understood and accepted by neighbour<strong>in</strong>g communities. As stressed earlier,a successful rural bus<strong>in</strong>ess must enjoy the support of the local community and efforts to<strong>in</strong>clude these people <strong>in</strong> the enterprise must be made.There is no history <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands (or the Pacific islands generally) of expropriationof commercial <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>. Governments have shown a clear understand<strong>in</strong>g of thedamage such action would do the country’s chances of attract<strong>in</strong>g further <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>.Solomon Islands subscribes to the APEC pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on non-expropriation and is amember of the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency, part of the <strong>World</strong> Bank Groupof <strong>in</strong>stitutions, which provides f<strong>in</strong>ancial guarantees aga<strong>in</strong>st expropriation of foreigncommercial <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>s by host governments. There is no significant expropriation riskto an <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> that is conducted <strong>in</strong> a commercially and legally conventional manner.4.1.4 Security of profitsThe Central Bank operates exchange control regulations under which authority toapprove and process rout<strong>in</strong>e trade transactions is delegated to commercial banks.18

Authorised exporters are allowed to reta<strong>in</strong> funds offshore to pay for imports to m<strong>in</strong>imise<strong>in</strong>ward and outward transaction costs.Capital movements require Central Bank approval, which is readily given on proof oflegal status and availability of funds, e.g. repatriation of declared dividends or of capitalon sale of an <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>. Anti-money-launder<strong>in</strong>g legislation requires banks to reportsuspicious transactions, and customers may be required to provide proof of their identityand nature of transactions.4.2 Taxation and <strong>in</strong>centives4.2.1 Tax structureThe profits of resident corporations are taxed at 30%, non-residents at 35%. Incalculat<strong>in</strong>g profit, deductions from <strong>in</strong>come are allowed only for costs <strong>in</strong>curred <strong>in</strong>produc<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong>come and capital expenditure is not normally a deductible expense, butdepreciation is deductible at prescribed rates. 100% deduction of capital expenditure isallowed for certa<strong>in</strong> agricultural, livestock and scientific purposes, and it should bepossible to make a good case for the same treatment to apply to development of <strong>pearl</strong>farm<strong>in</strong>g. Tax losses can be carried forward for up to five years provided there is nochange of shareholder control.Employers are required to deduct personal <strong>in</strong>come tax (PAYE) from their employees’wages and remit the proceeds to Inland Revenue. Individuals are taxed on an <strong>in</strong>crementalscale. (In this section $ means SBD) Above a personal allowance of $7800 per year,<strong>in</strong>come is taxed at 11% for the next $1-$15,000, 23% for the next $15,001-$30,000, 35%for the next $30,001-$60,000, and <strong>in</strong>come above this is taxed at 40%. An additionalrequired deduction is for the national superannuation fund to which employers contribute7.5% and employees 5%.Goods tax is charged though there are a number of categories of imported goods exemptfrom goods tax, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g scientific and research equipment. Exemption from goods taxfor any such equipment and other specialised imports required for <strong>pearl</strong> oysterdevelopment may be possible.Import duties have been greatly reduced over the last ten years as part of tradeliberalisation policy. When a schedule of technical and scientific equipment and otherspecialised imports is available, an <strong>in</strong>vestor should request exemption from import dutyon the <strong>in</strong>itial importation as a valuable form of assistance to undertake the <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>.4.2.2 IncentivesAn Exemptions Committee of the Inland Revenue Division considers requests for taxbreaks and makes recommendations to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue. Pearlfarm<strong>in</strong>g’s <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> cost and benefit profile is unusual and will require carefulexplanation to the tax authorities, but it should be possible to make a good case for tax19

<strong>in</strong>centive treatment that fits the likely profile. The most likely and useful bus<strong>in</strong>ess tax<strong>in</strong>centive available to a <strong>pearl</strong> farm <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> appears to be a tax holiday (exemptionfrom bus<strong>in</strong>ess profits tax) for a period of up to 10 years, the actual period to be decidedon basis of the projected performance of the bus<strong>in</strong>ess. A well argued case should obta<strong>in</strong>the maximum exemption. Many other countries offer such concessions for pioneer andrural <strong>in</strong>dustries, and for Solomon Island not to do so would reduce the relativeattractiveness of the country to foreign <strong>in</strong>vestors.As noted earlier, any <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dustry that develops <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands will dependon the services of foreign seed<strong>in</strong>g technicians, the majority of whom are Japanese. Inother countries regulations requir<strong>in</strong>g localisation of this work has led to a variety ofproblems for the <strong>in</strong>dustry. A clear statement by the Solomon Islands Government thatlicensed <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g operators will be entitled to receive work permits for foreignseed<strong>in</strong>g technicians will be an encouragement to <strong>in</strong>vestors with long-term <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong>horizons.One drawcard for a <strong>pearl</strong> farmer consider<strong>in</strong>g an <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands is theexist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> aquaculture facility at Nusa Tupe, <strong>in</strong> Western Prov<strong>in</strong>ce. Any <strong>in</strong>vestorwho could ga<strong>in</strong> access to this facility would immediately short-circuit the process ofidentify<strong>in</strong>g a suitable culture site and negotiat<strong>in</strong>g a lease agreement, and construct<strong>in</strong>gbasic operat<strong>in</strong>g facilities, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g a hatchery. If the stock of 2-3,000 adult black-lipshell currently be<strong>in</strong>g ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed at the facility were made available it could be implantedwith nuclei immediately, so that the farm would commence generat<strong>in</strong>g revenue <strong>in</strong> twoyears rather than the usual 4-5. Spat collection and/ or hatchery production arrangementswould still need to be developed so that the size of the farm could be progressively<strong>in</strong>creased, but the exist<strong>in</strong>g stock would accelerate the process of achiev<strong>in</strong>g positive cashflow and profitability.A cooperative venture with the <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong> should thus be a significant attractionto any <strong>in</strong>vestor <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> explor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands. This shouldmake it possible to leverage a cooperative venture which allows <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> and theSolomon Islands Government to cont<strong>in</strong>ue research on aspects of <strong>pearl</strong> oyster biology andlife history (growth rates, spat collection success, etc) or to access research <strong>in</strong>formationobta<strong>in</strong>ed by the commercial partner. Ultimately, if <strong>in</strong>itial success was achieved at the<strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> site, the company would need to negotiate its own site and facilities.4.3 LabourWork permits under the Employment Act and residence permits under the ImmigrationAct are required for foreign employees, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>vestor himself/herself. Theexpectation will be that Solomon Islanders are used where they can already undertake therequired work or when they can easily be tra<strong>in</strong>ed to do so. For <strong>pearl</strong> farms, policy willadvocate that local staff fill general labour<strong>in</strong>g, ma<strong>in</strong>tenance, boat driv<strong>in</strong>g and SCUBAdiv<strong>in</strong>g roles, though seed<strong>in</strong>g technicians need not be local and provision have beenproposed to ensure that they are freely able to obta<strong>in</strong> necessary work permits.20

Wages <strong>in</strong> formal jobs <strong>in</strong> rural areas range from SB$30-50 per day for semi-skilled toSB$100-$150 per day for skilled workers. The legal m<strong>in</strong>imum wage <strong>in</strong> agriculture, which<strong>in</strong>cludes mariculture, is SB$3.80 per hour or about SB$30 per day.An oyster farm could expect to recruit all its unskilled and semi-skilled workers locally –this would greatly assist with ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g harmonious relationships with localcommunities - and not be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> transport<strong>in</strong>g them to and from annual leave.Workers housed on site would receive free basic hous<strong>in</strong>g, water, sanitation and light<strong>in</strong>g.Supervisory and junior management pay <strong>in</strong> rural-based formal employment is <strong>in</strong> therange SB$30,000-$100,000 a year, plus free hous<strong>in</strong>g, water and electricity.4.4 Environmental impact assessment.Farm<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>pearl</strong> oysters will require an application for development consent under theEnvironment Act, 1998. The Director of Environment may require the preparation of apublic environmental report or an environmental impact assessment, which would bepublished. After periods for public reaction to such report or assessment have elapsed theDirector may issue the development consent with or without conditions, or may refuseconsent. Given the need for environmental care <strong>in</strong> the rear<strong>in</strong>g of oysters and the relativelysmall scale of the shoreside <strong>in</strong>stallations required, it is unlikely that environmentalobjections would arise <strong>in</strong> this case.Pearl farmers operat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands will also be encouraged to submit anenvironmental management plan (EMP) or code of practice (COP) as part of their licenceapplication. The purpose of the EMP or COP is to reassure the <strong>Fish</strong>eries M<strong>in</strong>istry that theoperator is cognisant of the environmental risks of <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g, will m<strong>in</strong>imise theenvironmental impacts of the operation, and has considered measures that may need to betaken <strong>in</strong> response to factors such as mass mortalities or disease outbreaks. It is expectedthat the presentation of an EMP or COP as part of the licence application will largelyobviate the need for a separate EIA by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Environment.5 Policy, Regulation and Management guidel<strong>in</strong>esDevelopment of sound policy and regulation is essential to the successful and long termestablishment of <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands (see Appendix VI). In other countries,poor control of the <strong>in</strong>dustry has eventually led to problems and low-quality <strong>pearl</strong>senter<strong>in</strong>g the market cha<strong>in</strong> have lowered the overall reputation of the <strong>in</strong>dustry. The FrenchPolynesian authorities have attempted to put <strong>in</strong> place an <strong>in</strong>dustry code of practice, anactive <strong>pearl</strong> market<strong>in</strong>g campaign that serves the <strong>in</strong>dustry as a whole, and a comprehensivesystem of quality control and certification, <strong>in</strong> which each <strong>pearl</strong> is sold along with an X-ray demonstrat<strong>in</strong>g the nacre thickness, as well as a government certificate of authenticity.These measures may have helped slow down the fall<strong>in</strong>g image and value of FrenchPolynesian <strong>pearl</strong>s, but have not completely arrested it, and the <strong>in</strong>dustry cont<strong>in</strong>ues todecl<strong>in</strong>e. There is still a great deal of leakage, with large volumes of poor quality <strong>pearl</strong>s21

cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g to enter the market. This underm<strong>in</strong>es attempts by both government and largescaleproducers to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> the rarity value and exclusive image of their product.The second most important producer <strong>in</strong> the Pacific Islands region is Cook Islands, wherethe <strong>in</strong>dustry was catalysed largely by developers from neighbour<strong>in</strong>g French Polynesiawho brought technical skills and <strong><strong>in</strong>vestment</strong> funds to the country. The Cook Islands<strong>in</strong>dustry produced about US$18 million worth of <strong>pearl</strong>s at its peak <strong>in</strong> 2000, but hasdecl<strong>in</strong>ed s<strong>in</strong>ce that time, with production of only about US$2 million <strong>in</strong> 2005. A majordisease outbreak at the end of 2000, attributed ma<strong>in</strong>ly to overstock<strong>in</strong>g and poor farm<strong>in</strong>gpractices, decimated the <strong>in</strong>dustry, and it has still not fully recovered. Cook Islands hassuffered more development problems than French Polynesia, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong> addition todisease, conflicts among farmers and persistent market<strong>in</strong>g of low-grade <strong>pearl</strong>s, which hasunderm<strong>in</strong>ed prices <strong>in</strong> general and given Cook Islands a widespread reputation as aproducer of a low-grade product. These examples highlight the importance of sett<strong>in</strong>gstrict controls at the outset of any new <strong>pearl</strong> venture.5.1 PolicyThe current government’s stated policy goal for the fisheries sector is ‘the developmentand susta<strong>in</strong>able utilisation of sea and mar<strong>in</strong>e resources to benefit and contribute to thewell be<strong>in</strong>g of Solomon Islanders’. The policy is accompanied by eight expected outcomesand a series of associated strategies, most of which relate to manag<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>geconomic benefits from capture fisheries, especially tunas. None of the outcomes orstrategies make any reference to aquaculture.MFMR’s Aquaculture Development Plan (here<strong>in</strong>after referred to as the Plan) conta<strong>in</strong>s anumber of statements of policy <strong>in</strong> regard to aquaculture <strong>in</strong> general and <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>particular. The Plan recognises that the M<strong>in</strong>istry lacks knowledge and experience ofaquaculture, and that <strong>in</strong>stitutional strengthen<strong>in</strong>g and human resource development arerequired. It also acknowledges the absence of appropriate policies and regulations foraquaculture, and urges the development of these. Not<strong>in</strong>g that the <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> <strong>Center</strong>operates the only aquaculture hatchery <strong>in</strong> Solomon Islands, the Plan recommends aga<strong>in</strong>stthe development of further hatcheries by government, although it encourages governmentsupport to the private sector <strong>in</strong> regard to hatchery development. Section 9 of the Planstates that MFMR will provide <strong>in</strong>formation to prospective aquaculture <strong>in</strong>vestors <strong>in</strong> regardto land and sea tenure, licens<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>frastructure and transportation, among other th<strong>in</strong>gs. Inregard to <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g, proposed actions by MFMR are: Collaborate with <strong>World</strong><strong>Fish</strong> and EU to attract private <strong>in</strong>vestors <strong>in</strong> SolomonIslands; Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> the ban on the wild shell trade; Implement the policies and licens<strong>in</strong>g conditions developed by the EU-fundedproject; Provide extension services for the participation of local communities throughProv<strong>in</strong>cial <strong>Fish</strong>eries Officer, after the establishment of private farms; Promote value added <strong>pearl</strong> oyster products particularly for rural communities <strong>in</strong>opportunities such as shell carv<strong>in</strong>gs or <strong>pearl</strong> mabe handicrafts.22

At present there is no policy or management framework specifically <strong>in</strong>tended for the<strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g sector. The development of such a framework for an as-yet non-existent<strong>in</strong>dustry may be regarded by some as somewhat premature and liable to discourage<strong>in</strong>vestors. However <strong>in</strong> other Pacific Island countries where the <strong>pearl</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry hasdeveloped the absence of any regulatory framework has led to major problems whichhave had to be addressed once the <strong>in</strong>dustry was already <strong>in</strong> a crisis. As with fisheriesmanagement, it is far better to learn from experience, anticipate problem areas and set the‘rules of the game’ beforehand, rather than wait until the problems occur.Properly formulated management guidel<strong>in</strong>es should also be a source of reassurance tolegitimate <strong>in</strong>vestors with a long time horizon. Bona fide <strong>in</strong>vestors will prefer to operatewith<strong>in</strong> a framework <strong>in</strong> which ‘the rules of the game’ are already <strong>in</strong> place and clearlyspelled out, rather than <strong>in</strong> an uncerta<strong>in</strong> environment where policy and regulations areignored until there is a crisis, or are developed accord<strong>in</strong>g to the whims of governmentm<strong>in</strong>isters or public servants.5.2 LegislationSeveral government documents perta<strong>in</strong> to the management of fisheries aquaculture <strong>in</strong>Solomon Islands. Chief amongst these are the <strong>Fish</strong>eries Act (1998), <strong>Fish</strong>eries Regulations(2002) and the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Fish</strong>eries and Mar<strong>in</strong>e Resources’ Aquaculture DevelopmentPlan.Responsibility for the management and development of Solomon Islands’ mar<strong>in</strong>eresources lies with the M<strong>in</strong>istry of <strong>Fish</strong>eries and Mar<strong>in</strong>e Resources (MFMR). The<strong>Fish</strong>eries Act (1998) (here<strong>in</strong>after referred to as the Act), is the major piece of legislationgovern<strong>in</strong>g fisheries and fisheries-related activities. The Act is currently (August 2008)under review, but until new legislation is fully adopted will cont<strong>in</strong>ue to apply to anyprospective <strong>pearl</strong> farm<strong>in</strong>g activities. The Act provides the basic legal framework fromwhich other subsidiary controls can be derived but <strong>in</strong> itself has m<strong>in</strong>imal direct applicationto the overall control of aquaculture. The Act does not dist<strong>in</strong>guish aquaculture from otherfish<strong>in</strong>g methods or fisheries, and the applicability of some provisions to aquaculturecontrol is unclear. The Act does however have certa<strong>in</strong> relevant provisions, as follows:Section 31, Aquaculture Operations, requires the written permission of the Director of<strong>Fish</strong>eries, with or without conditions, for the sett<strong>in</strong>g up and operation of an aquacultureactivity. Conditions that may be specified with a written approval deal with issues such as‘the location of the aquaculture facilities and its operation, the prevention of the spread ofcommunicable fish diseases, the <strong>in</strong>spection of aquaculture sites and the provision ofstatistical <strong>in</strong>formation’. Contravention of the provisions of this section <strong>in</strong>vokes a penaltyof up to SI$ 100,000 on conviction.Section 32, Import and Export of Live <strong>Fish</strong>, prevents the import or export of live fishwithout the Director’s permission. The section imposes an assessment on the possibleimpacts of imported live fish be<strong>in</strong>g released <strong>in</strong>to the wild. Contravention of theprovisions of this section <strong>in</strong>vokes a penalty of up to SI$ 500,000 on conviction.23