Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics - AToL Decapoda - Natural ...

Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics - AToL Decapoda - Natural ...

Decapod Crustacean Phylogenetics - AToL Decapoda - Natural ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

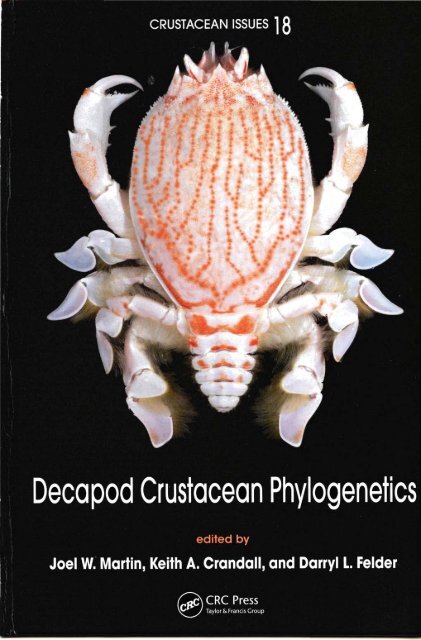

CRUSTACEAN ISSUES ] 3<br />

%. m<br />

II<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong> <strong>Phylogenetics</strong><br />

edited by<br />

Joel W. Martin, Keith A. Crandall, and Darryl L. Felder<br />

£\ CRC Press<br />

J Taylor & Francis Group

<strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong> <strong>Phylogenetics</strong><br />

Edited by<br />

Joel W. Martin<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> History Museum of L. A. County<br />

Los Angeles, California, U.S.A.<br />

KeithA.Crandall<br />

Brigham Young University<br />

Provo,Utah,U.S.A.<br />

Darryl L. Felder<br />

University of Louisiana<br />

Lafayette, Louisiana, U. S. A.<br />

CRC Press is an imprint of the<br />

Taylor & Francis Croup, an informa business

CRC Press<br />

Taylor & Francis Group<br />

6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300<br />

Boca Raton, Fl. 33487 2742<br />

Contents<br />

Preface<br />

JOEL W. MARTIN, KEITH A. CRANDALL & DARRYL L. FELDER<br />

I Overviews of <strong>Decapod</strong> Phylogeny<br />

On the Origin of <strong>Decapod</strong>a<br />

FREDERICK R. SCHRAM<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Phylogenetics</strong> and Molecular Evolution 15<br />

ALICIA TOON. MAEGAN FINLEY. JEFFREY STAPLES & KEITH A. CRANDALL<br />

Development, Genes, and <strong>Decapod</strong> Evolution 31<br />

GERHARD SCHOLTZ. ARKHAT ABZHANOV. FREDERIKR ALWES. CATERINA<br />

BIEFIS & JULIA PINT<br />

Mitochondrial DNA and <strong>Decapod</strong> Phylogenies: The Importance of 47<br />

Pseudogenes and Primer Optimization<br />

CHRISTOPH D. SCHUBART<br />

Phylogenetic Inference Using Molecular Data 67<br />

FERRAN PALERO & KEITH A. CRANDALL<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong> Phylogeny: What Can Protein-Coding Genes Tell Us? 89<br />

K.H. CHU, L.M. TSANG. K.Y. MA. T.Y. CHAN & P.K.L. NG<br />

Spermatozoal Morphology and Its Bearing on <strong>Decapod</strong> Phylogeny 101<br />

CHRISTOPHER TUDGE<br />

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 121<br />

AKIRA ASAKURA<br />

A Shrimp's Eye View of Evolution: How Useful Are Visual Characters in 183<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Phylogenetics</strong>?<br />

MEGAN L. PORTER & THOMAS W. CRONIN<br />

<strong>Crustacean</strong> Parasites as Phylogenetic Indicators in <strong>Decapod</strong> Evolution 197<br />

CHRISTOPHER B. BOYKO & JASON D. WILLIAMS<br />

The Bearing of Larval Morphology on Brachyuran Phylogeny 221<br />

PAUL F. CLARK

vi Contents<br />

II Advances in Our Knowledge of Shrimp-Like <strong>Decapod</strong>s<br />

Evolution and Radiation of Shrimp-Like <strong>Decapod</strong>s: An Overview 245<br />

CHARLES H..I.M. ERANSEN & SAMMY DE GRAVE<br />

A Preliminary Phylogenelic Analysis of the Dendrobranchiata Based on 261<br />

Morphological Characters<br />

CAROLINA TAVARES. CRISTIANA SERE.IO & JOEL W. MARTIN<br />

Phvlogeny of the Infraorder Caridea Based on Mitochondrial and Nuclear 281<br />

Genes (Crustacea: <strong>Decapod</strong>a)<br />

HEATHER D. BRACKEN. SAMMY DE GRAVE & DARRYL L. FEEDER<br />

III Advances in Our Knowledge of the Thalassinidean<br />

and Lobster-Like Groups<br />

Molecular Phylogeny of the Thalassinidea Based on Nuclear and 309<br />

Mitochondrial Genes<br />

RAFAEL ROBLES. CHRISTOPHER C. TUDGE, PETER C. DWORSCHAK, GARY C.B.<br />

POORE & DARRYL L. FBLDER<br />

Molecular Phylogeny of the Family Callianassidae Based on Preliminary 327<br />

Analyses of Two Mitochondrial Genes<br />

DARRYL L. FELDER & RAFAEL ROBLES<br />

The Timing of the Diversification of the Freshwater Crayfishes 343<br />

JESSE BREINHOLT. MARCOS PEREZ-LOSADA & KEITH A. CRANDALL<br />

Phylogeny of Marine Clawed Lobster Families Nephropidae Dana. 1852. 357<br />

and Thaumastochelidae Bate. 1888, Based on Mitochondrial Genes<br />

DALE TSHUDY. RAFAEL ROBLES. TIN-YAM CHAN, KA CHAI HO. KA HOU CHU,<br />

SHANE T. AHYONG & DARRYL L. FELDER<br />

The Polychelidan Lobsters: Phylogeny and Systematics (Polychelida: 369<br />

Polychelidae)<br />

SHANE T. AHYONG<br />

IV Advances in Our Knowledge of the Anomttra<br />

Anomuran Phylogeny: New Insights from Molecular Data 399<br />

SHANE T. AHYONG, KAREEN E. SCHNABHL & ELIZABETH W. MAAS<br />

V Advances in Our Knowledge of the Brachyura<br />

Is the Brachyura Podotremata a Monophyletic Group? 417<br />

GERHARD SCHOLTZ & COLIN L. MCLAY

Contents vii<br />

Assessing the Contribution of Molecular and Larval Morphological 437<br />

Characters in a Combined Phylogenetic Analysis of the Supcrfamily<br />

Majoidea<br />

KRISTIN M. HUI.TGREN, GUILLERMO GUHRAO, HERNANDO RL. MARQUES &<br />

EHRRAN P. PALERO<br />

Molecular Genetic Re-Examination of Subfamilies and Polyphyly in the 457<br />

Family Pinnotheridae (Crustacea: <strong>Decapod</strong>a)<br />

EMMA PALACIOS-THEIL. JOSE A. CUESTA. ERNESTO CAMPOS & DARRYL L.<br />

FELDER<br />

Evolutionary Origin of the Gall Crabs (Family Cryptochiridae) Based on 475<br />

16S rDNA Sequence Data<br />

REGINA WETZER. JOEL W. MARTIN & SARAH L. BOYCE<br />

Systematics, Evolution, and Biogeography of Freshwater Crabs 491<br />

NEIL CUMBERLIDGE & PETER K.L. NG<br />

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Asian Freshwater Crabs of the Family 509<br />

Gecarcinucidae (Brachyura: Potamoidea)<br />

SEBASTIAN KLAUS. DIRK BRANDIS. PETER K.L. NG. DARREN C.J. YEO<br />

& CHRISTOPH D. SCHUBART<br />

A Proposal for a New Classification of Porlunoidea and Cancroidea 533<br />

(Brachyura: Heterotremata) Based on Two Independent Molecular<br />

Phylogenies<br />

CHRISTOPH D. SCHUBART & SILKE RRUSCHRL<br />

Molecular Phylogeny of Western Atlantic Representatives of the Genus 551<br />

Hexapanopeus (<strong>Decapod</strong>a: Brachyura: Panopeidae)<br />

BRENT P. THOMA. CHRISTOPH D. SCHUBART & DARRYL L. FELDER<br />

Molecular Phylogeny of the Genus Cronius Stimpson, I860, with 567<br />

Reassignment of C. tumidulus and Several American Species ol' Port un us<br />

to the Genus Achelous De Haan, 1833 (Brachyura: Portunidae)<br />

FERNANDO L. MANTELATTO. RAFAEL ROBLES. CHRISTOPH D. SCHUBART<br />

& DARRYL L. FELDER<br />

Index 581<br />

Color Insert

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s<br />

AKIRAASAKURA<br />

<strong>Natural</strong> History Museum & Institute, Chiba, Japan<br />

ABSTRACT<br />

The mating systems of decapod crustaceans are reviewed and classified according to general patterns<br />

of lifestyles and male-female relations. The scheme employs criteria that focus on ecological, life<br />

history, and social determinants of both male and female behavior, and by these criteria nine types of<br />

mating systems are distinguished: (1) Short courtship: Both males and females are free-living (= not<br />

symbiotic with other organisms), and copulation occurs after brief behavioral interactions between a<br />

male and a female. (2) Precopulatory guarding: A male guards a mature female one to several days<br />

before copulation; both males and females are generally free-living. (3) Podding: In some largesize<br />

decapods, aggregations consisting of an extremely large number of individuals are formed, and<br />

mating occurs inside those aggregations. (4) Pair-bonding: In many symbiotic and some free-living<br />

species, males and females are found in a heterosexual pair and are regarded as having a monogamous<br />

mating system. They may live on or inside other organisms such as sponges, corals, molluscs,<br />

polychaetes, sea urchins, ascidians, and algal tubes. (5) Eusocial: In some sponge-dwelling snapping<br />

shrimps, a colony of shrimps contains a single reproductive female and many small individuals<br />

that apparently never breed. (6) Waving display: In many intertidal and semi-terrestrial crabs inhabiting<br />

mudflats or sandy beaches, males conduct visual displays that include species-specific dances<br />

to attract females. (7) Visiting: In some hapalocarcinid crabs, females are sealed inside a coral gall,<br />

and the male crab normally residing outside the gall is assumed to visit the gall for mating. (8)<br />

Reproductive swarm: In some pinnotherid crabs, mating occurs when a female is a free-swimming<br />

instar before she enters her definitive host. (9) Dwarf male mating: In some anomuran sand crabs,<br />

an extremely small male attaches near the gonopore of a free-living female.<br />

1 INTRODUCTION<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong> crustaceans are a large and diverse assemblage of animals. In most decapods, the sexes<br />

live separately and pair briefly as adults. Pairs are formed after a brief display, the sexes remain<br />

together for a relatively short period, the sexes separate after copulation, and the females assume<br />

all further parental duties such as selecting suitable habitat for egg incubation, aeration, and cleaning<br />

(Salmon 1983). However, recent discoveries of often-conspicuous behavior and male-female<br />

relations among decapods have shown that their mating system is highly diverse and is sometimes<br />

quite similar to mating systems of other animals such as birds, mammals, reptiles, and insects (see<br />

Shuster & Wade 2003; Duffy & Thiel 2007 for a review).<br />

As claimed by Emlen & Oring (1977) in their classic work on the relationships among ecological<br />

factors, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating system, sexual selection is the driving force that<br />

underlies the evolution of male-male competition and female choice. However, ecological factors<br />

apparently contribute to the evolution of mating systems as well as to behavioral and morphological<br />

differences between the sexes. From this point of view, much study has been conducted recently on<br />

the evolution of the mating system of decapods (see section 2 below).

122 Asakura<br />

In this paper, I describe the diversity of mating systems of decapods in an attempt to recognize<br />

and classify their general patterns from the viewpoints of the ecological, life history, and social determinants<br />

of both male and female behavior. Historically, there are two ways of describing mating<br />

systems (Shuster & Wade 2003). The first is in behavioral ecology, where mating systems are usually<br />

described in terms of the number of mates per male or female, such as monogamy, polygyny, and<br />

polyandry. The second is in terms of the genetic relationships between mating males and females,<br />

such as random mating, negative assortative mating (outbreeding), and positive assortative mating<br />

(inbreeding). My approach to describing mating systems of decapods is a "recognition of general<br />

pattern" approach, a kind of a combination of these two approaches that captures variation in the<br />

relationship between male and female, from promiscuity to monogamy, as well as the relationship<br />

between male guarding and the female tendency to settle down in certain places or to aggregate, and<br />

the complex nature of eusociality.<br />

Terminology generally follows Duffy & Thiel (2007). Additionally, some basic terms are redefined<br />

here, because these terms are sometimes used in more or less different ways according to taxa,<br />

including birds, mammals, and fish:<br />

• Monogamy (= pair bonding): One male and one female have an exclusive mating relationship.<br />

• Polygamy: One or more males have an exclusive relationship with one or more females. Three<br />

types are recognized: polygyny, where one male has an exclusive relationship with two or more<br />

females; polyandry, where one female has an exclusive relationship with two or more males;<br />

and polygynandry, where two or more males have an exclusive relationship with two or more<br />

females (the numbers of males and females need not be equal, and, in vertebrate species studied<br />

so far, the number of males is usually fewer).<br />

• Promiscuity: Any male within the group mates with any female.<br />

• Eusociality: Multigenerational (cohabitation of different generations), cooperative colonies with<br />

strong reproductive skew (reproductive division of labor, usually a single breeding female) and<br />

cooperative defense of the colony (after Duffy 2003).<br />

• Symbiosis: Here defined simply as dissimilar organisms living together.<br />

2 HISTORY OF STUDY<br />

The first important review of decapod mating systems was Hartnoll's (1969) publication on brachyuran<br />

crabs. He distinguished two types of mating systems. "Soft-female mating" was defined as copulation<br />

occurring immediately after molting of the female, usually preceded by a lengthy pre-molt<br />

courtship behavior including precopulatory guarding by the male. "Hard-female mating" was defined<br />

as mating in which the female copulates during the intermolt stage after a relatively brief<br />

courtship behavior.<br />

Through their intensive study of the harlequin shrimp Hymenocera picta, Wickler & Seibt (see<br />

Reference 16 in Appendix I, Table 10) found that these shrimp form stable heterosexual pairs based<br />

on individual recognition by chemical cues at a distance. Wickler & Seibt discussed several similar<br />

hypotheses, independently developed in research on crustaceans and humans, for the evolution of<br />

monogamy and other mating systems. Individual recognition in the monogamous mating system<br />

was intensively studied in the banded shrimp Stenopus hispidus by Johnson (1969, 1977).<br />

The report by Emlen & Oring (1977) was influential for studies on crustacean mating systems.<br />

They classified the mating system into the following categories:<br />

1. Monogamy<br />

2. Polygyny (subdivided into 2a, resource defense polygyny; 2b, female (or harem) defense<br />

polygyny; and 2c, male dominance polygyny (further subdivided into 2c-1, explosive breeding<br />

assemblages, and 2c-2, leks))

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 123<br />

3. Rapid multiple clutch polygamy<br />

4. Polyandry (subdivided into 4a, resource defense polyandry; and 4b, female access polyandry)<br />

Ridley (1983) intensively reviewed the precopulatory mate guarding behavior in various groups<br />

of animals including tardigrades, crustaceans, arachnids, and anurans, and discussed its evolution.<br />

Work on the behavior of the fiddler crabs (genus Uca) has contributed greatly to our understanding<br />

of the mating systems of brachyuran crabs. These studies include the works of H.O. von Hagen<br />

(e.g., von Hagen 1970), J. Crane (e.g., Crane 1975), J. Christy and his coworkers (e.g., Christy<br />

et al. 2003a, b), M. Salmon and his coworkers (e.g., Salmon & Hyatt 1979), R R. Y. Backwell and<br />

her coworkers (e.g., Backwell et al. 2000), M. Murai and his coworkers (e.g., Murai et al. 2002),<br />

and T. Yamaguchi (e.g., Yamaguchi 2001a, b). Based on the studies of Uca and other brachyurans,<br />

as well as other decapods, Salmon (1983) reported the diversity of behavioral interactions<br />

preceding mating in decapods, and he defined some of the consequences of these interactions in<br />

terms of sexual selection, courtship behavior, and mating systems. The book edited by Reback &<br />

Dunham (1983), which included Salmon's (1983) work, was a landmark in the study of decapod<br />

behavior.<br />

Christy (1987) reviewed the mating systems of brachyuran crabs and classified them, according<br />

to modes of competition among males for females, into three major categories and eight subcategories,<br />

as follows.<br />

1. Female-centered competition, including: la, defense of mobile females following free search;<br />

lb, defense of sedentary females following a restricted search; lc, capture, carrying, and<br />

defense of females at protected mating sites; and Id, attraction and defense of females at<br />

protected mating sites<br />

2. Resource-centered competition, including: 2a, defense of breeding sites; and 2b, defense of<br />

refuges<br />

3. Encounter rate competition, including: 3a, neighborhoods of dominance; and 3b, pure search<br />

and interception<br />

In their book on crustacean sexual biology, Bauer & Martin (1991) introduced developments in<br />

various fields and taxa of crustacean research, including studies on sex attraction, sex recognition,<br />

mating behavior, mating system, and structure and function associated with insemination. Bauer and<br />

his coworkers have extensively studied the mating behavior, mating system, and hermaphroditism<br />

of shrimps (e.g., see Bauer 2004 for a review).<br />

Through their intensive studies on the mating system of the spider crab Inachus and of the extended<br />

maternal care of semi-terrestrial grapsid crabs of Jamaica, Diesel and his coworker revealed<br />

examples of highly specialized mating and social systems in these crabs (see Diesel 1991; Diesel &<br />

Schubart 2D07 for reviews).<br />

Thiel and his students have conducted intensive research on the mating system of rock shrimps<br />

(see Reference 6 in Appendix I, Table 4) and symbiotic anomuran crabs (e.g., Baeza & Thiel 2003).<br />

Based on these studies, Thiel & Baeza (2001) and Baeza & Thiel (2007) reviewed factors affecting<br />

the social behavior of marine crustaceans living symbolically with other invertebrates. Similarly,<br />

Correa & Thiel (2003) reviewed mating systems in caridean shrimp and their evolutionary consequences<br />

for sexual dimorphism and reproductive biology. The book by Duffy & Thiel (2007) on the<br />

evolutionary ecology of social and sexual systems of crustaceans is a monumental landmark that<br />

synthesizes the state of the field in crustacean behavior and sociobiology and places it in a conceptually<br />

based, comparative framework. The relatively recent discovery of eusociality in snapping<br />

shrimp by Duffy has opened the door to a new field in social and mating systems of decapods (see<br />

Duffy 2007 for a review; see also sections 3.5 Eusocial type and 4.5 Evolution of the eusocial type<br />

below for further explanation).

124 Asakura<br />

Asakura (1987, 1990, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998a, 1998b, 1999, 2001a, b, c), Imazu & Asakura<br />

(1994, 2006), and Nomura & Asakura (1998) reported mating systems and various aspects of sexual<br />

differences in the ecology and behavior of hermit crabs and other decapods.<br />

3 TYPES OF MATING SYSTEMS<br />

3.1 Short courtship type<br />

This type is generally seen in species whose males and females are free living, that is, not symbiotic<br />

with other organisms (Appendix 1, Tables 1, 2). Copulation occurs after a short courtship behavior<br />

by the male, or copulation occurs just after brief behavioral interactions between a male and a<br />

female. This type of courtship includes very different groups of decapods, from the most primitive<br />

group (dendrobranchiate shrimps) to groups specialized for certain habitats such as freshwater crayfishes,<br />

intertidal hermit crabs, and semi-terrestrial and terrestrial brachyuran crabs. It is perhaps the<br />

most widely seen mating system in decapods.<br />

No intensive aggressive behavior between males (for a female) has been reported in species of<br />

dendrobranchiate shrimps of the families Penaeidae and Sicyoniidae, caridean shrimps of the families<br />

Palaemonidae, Hyppolytidae, and Pandalidae, or anomuran sand crabs of the family Hippidae.<br />

In these species, females are generally similar in size to, or larger than, males. On the other hand,<br />

strong aggressive interaction is seen between males in freshwater crayfish species of all three families<br />

(Astacidae, Parastasidae and Cambaridae) as well as in brachyuran crabs of the Grapsoidea and<br />

Gecarcinidae. In these species, the male body and weaponry (chelipeds) are generally larger than<br />

the female.<br />

Among decapods exhibiting this mating system are species whose females molt before copulation<br />

(Appendix 1, Table 1) and those whose females do not molt before copulation (Appendix 1,<br />

Table 2). In species inhabiting terrestrial and semi-terrestrial habitats, females generally copulate<br />

in the hard shell condition; these species include land hermit crabs of the genus Coenobita and<br />

brachyuran crabs of the Grapsoidea and Gecarcinidae.<br />

In penaeid shrimp, the molting condition of copulating females is determined according to the<br />

type of thelycum. The thelycum is the female genital area, i.e., modifications of female thoracic<br />

sternites 7 and 8 (sometimes including thoracic sternite 6) that are related to sperm transfer and<br />

storage. A female with externally deposited spermatophores is said to have an "open thelycum,"<br />

which is formed by modifications of the posterior coxae and sternites to which the spermatophores<br />

attach. Primitive dendrobranchiate shrimps, including species of the families Aristeidae, Solenoceridae,<br />

Benthesicymidae, and the penaeid genus Litopenaeus, have open thelyca. In these species,<br />

females copulate in the hard shell condition. On the other hand, a "closed thelycum" refers to sternal<br />

plates that may (1) enclose a noninvaginated seminal or sperm receptacle, (2) cover a space that<br />

leads to spermathecal opening, or (3) form an external shield guarding the spermathecal openings.<br />

In the most advanced groups, including the penaeoid genera Fenneropenaeus, Penaeus, Farfantepenaeus,<br />

Melicertus, Marsupenaeus, Trachypenaeus, and Xiphopenaeus, females have closed thelyca.<br />

In these species, females molt just before copulation. Since no significant difference is seen in mating<br />

behavior between the open thelycum species and the closed thelycum species, Hartnoll's (1969)<br />

rule, which predicts a lengthy pre-molt courtship behavior associated with soft-female mating and a<br />

relatively brief courtship behavior with hard-female mating, does not hold in the case of the penaeid<br />

shrimps.<br />

A sperm plug, which is believed to preclude subsequent insemination by other males, is known<br />

in some species of Farfantepenaeus, Marsupenaeus, Metapenaeus, and Rimapenaeus (Appendix 1,<br />

Table 3).<br />

In all the above-mentioned taxa, copulation generally continues only for several minutes. After<br />

mating, the male separates from the female and presumably goes on to search for other females.

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 125<br />

The habitat of species that exhibit this mating system varies, ranging from terrestrial through intertidal<br />

to deep water.<br />

3.2 Precopulatory guarding type<br />

This mating system also is generally seen in species whose males and females are free living<br />

(Appendix 1, Table 4). A male guards a mature female for one to several days before copulation.<br />

Generally, males aggressively fight for a female using their cheliped(s) and sometimes also the ambulatory<br />

pereopods. In some species, females always molt prior to mating and copulation; in other<br />

species, females may or may not molt prior to copulation. There are two types of guarding: (1) contact<br />

guarding of hermit crabs and brachyuran crabs, in which a male grasps part of the appendages,<br />

the body, or the shell (in the case of hermit crabs) of a mature female, and (2) non-contact guarding,<br />

as exhibited in Macrobrachium shrimps and Homarus lobsters, in which a male keeps a female<br />

without grasping her. After mating, postcopulatory guarding by a male for a female is sometimes<br />

observed (Appendix 1, Table 5). However, after postcopulatory guarding, or just after copulation,<br />

the male and female separate so that both may later mate with other individuals. Generally, in this<br />

mating system, the body size of males is larger than that of females, or weaponry (chelipeds) is<br />

more developed in males than in females.<br />

Species of the river prawn genus Macrobrachium are well known for the extremely long chelipeds<br />

in males. A male guards a female for one to several days before copulation and fights with<br />

other males using these chelipeds. In some species, such as M. australiense, a male has a nest (a<br />

saucer-shaped depression on the bottom), beckons a female to the nest, and guards and copulates<br />

with her in the nest. In the American lobster Homarus americanus, a male guards a female in his<br />

shelter, which is dug under rocks, boulders, or eelgrass, and the cohabitation of a male and a female<br />

lasts from one to three weeks.<br />

In hermit crabs of the genus Diogenes (Diogenidae) and in many species of the family Paguridae,<br />

al of which have unequal chelipeds in terms of both size and morphology, a male grasps the rim<br />

of the shell inhabited by a mature female by the minor cheliped, guards her for one to several<br />

days before copulation, and fights with other males approaching him using the major cheliped.<br />

In crab-shaped anomurans, the male Paralithodes brevipes conducts both pre-copulatory and postcopulatory<br />

guarding. The male claims a female by grasping her chelae or legs with his chelae, or<br />

he covers the female with his body. Similarly, the male Hapalogaster dentata grasps a female with<br />

his left chela and covers the female with his body; these guarding behaviors occur one to three days<br />

before copulation.<br />

In the brachyuran crab Corystes cassivelaunus (Corystidae), the male carries the female in his<br />

chelae, and, while stationary, holds one or both of the female's chelae in his own and holds her<br />

carapace close to his sternum. Such behavior continues up to several days before copulation. In<br />

species of the Cancridae and Portunidae, males carry the pre-molt female with her carapace or sternum<br />

held against the sternum of the male for a period of days; after this period the male releases<br />

the female so that she molts, and copulation occurs shortly after the molting. In many species in<br />

these two families, the male continues to carry the female after copulation in the pre-molt position<br />

until her integument has partially hardened. Sperm plugs, which are regarded as being produced<br />

by the males to block the females' genital duct to preclude subsequent insemination by other males<br />

(Diesel 1991), also are often reported for species of these families (Appendix 1, Table 6). In Menippe<br />

mercenaria (Xanthidae), the male guards the entrance to the burrow occupied by the pre-molt female,<br />

and they copulate as soon as the female molts. In species of the Majidae and Cheiragonidae,<br />

the male guards the female before copulation in a manner similar to what is seen in the Cancridae<br />

and Portunidae, where the male grasps the ambulatory pereopods, chelipeds, or body of the<br />

female.<br />

Species that exhibit this mating system are from the intertidal through shallow water to deep<br />

waters, but they are not found in terrestrial or semi-terrestrial environments.

126 Asakura<br />

3.3 Podding<br />

In large decapods inhabiting shallow waters, an aggregation consisting of an extremely large number<br />

of individuals in certain places is called a "pod." Podding is regarded as a type of behavior that is<br />

optional and that is associated with different stages in the species' life history, such as molting, mating,<br />

and the incubation period (Appendix 1, Table 7). The pod is also called a "heap" or "mound,"<br />

according to the locality and/or the species.<br />

The function of the pod may vary depending on the condition of the specimens within it (such as<br />

level of maturity, sex, intermolt stage) and possibly on changes in habitat condition, such as water<br />

temperature and presence of predators (Sampedro & Gonzalez-Gurriaran 2004). However, as listed<br />

in Appendix 1, Table 7, pods in some species have the function of facilitating mating, so I will treat<br />

this as a special kind of mass mating in some species.<br />

Stevens (2003) and Stevens et al. (1994), reporting more than 200 pods with a total of 100,000<br />

crabs of the majid Chionoecetes bairdi in an area of only 2 ha off Kodiak Island in Alaska in 1991,<br />

observed that the formation of the pods and mating synchronized with the spring tide. Similar observations<br />

were made for another majid, Hyas lyratus, by Stevens et al. (1992), who reported large<br />

aggregations during the mating season from off Kodiak Island. They found 200 mating pairs (males<br />

grasping females) among 2000 individuals in one pod. The majid crab Loxorhynchus grandis, distributed<br />

along the east coast of North America, often forms large aggregations numbering hundreds.<br />

of animals. The aggregation is composed of crabs of both sexes, and the function is thought to be<br />

the attraction of males for mating (Hobday & Rumsey 1999). DeGoursey & Auster (1992) reported<br />

large mating aggregations in another majid crab, Libinia emarginata, in April and May 1989. Many<br />

mating pairs were found in the aggregations, and the percentage of ovigerous females among all<br />

females increased from 26% on 1 May to 100% on 14 May. Males paired with females were significantly<br />

larger than unpaired males, while the paired and unpaired females were not significantly<br />

different in size. Carlisle (1957) monitored a pod consisting of 60-80 individuals of the majid crab<br />

Maja squinado in shallow waters in the English Channel; 20 were adult males and the rest were<br />

juvenile males and females in equal amounts. He observed crabs molting inside the pod and mating<br />

between intermolt males and postmolt females, which led him to conclude that the main purpose<br />

of podding is to provide protection for newly molted soft crabs against predators and to facilitate<br />

mating. However, later behavioral observations by Hartnoll (1969) indicated that copulation occurs<br />

between a male and a female in the intermolt stage. Furthermore, Sampedro & Gonzalez-Gurriaran<br />

(2004) found that the gonads of females in the pods were in an early stage of development (= not<br />

fully matured) and that the spermathecae were empty, suggesting to them that mating of this species<br />

occurs in deeper waters.<br />

In crab-shaped anomurans, large pods of the red king crab Paralithodes camtschaticus are well<br />

known in the northern Pacific Ocean, with each pod consisting of thousands of crabs in the 2-4<br />

year class (juveniles). Aggregations of adult red king crabs (ovigerous females) also were reported<br />

and are thought to be related to mating (Stone et al. 1993), but detailed surveys have not been<br />

conducted. Dense aggregations of the southern king crab Lithodes santolla have been reported from<br />

Chile (South America); however, the crabs forming these aggregations are juveniles, so this behavior<br />

is not thought be related to mating (Cardenas et al. 2007).<br />

In summary, podding is known only in large species distributed in temperate or boreal waters in<br />

both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.<br />

3.4 Pair-bonding type<br />

Many species of decapods, in particular those that are symbiotic with other animals, have been<br />

reported as "found in a heterosexual pair" (Appendix 1, Tables 8-12). Most of these are considered

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 111<br />

to have a monogamous mating system, which is well known in birds and mammals. In species whose<br />

males engage in mate-guarding, temporal heterosexual pairing occurs, where the pair is formed<br />

when the female is close to molting or spawning a new batch of unfertilized eggs, and the mateguarding<br />

males abandon the females soon after the eggs are fertilized. However, in pair-bonding<br />

species, males cohabit with females, independent of their reproductive status or of the stage of<br />

development of the brooded embryos. Nevertheless, the observations for the monogamous nature<br />

of these pair-bonding species are often only anecdotal, and how long the pair remains together, and<br />

with whom they mate, is rarely recorded. Some well-documented studies include the formation of<br />

stable pairing and individual recognition (individuals in a pair can recognize each other as mates),<br />

as in the case of the banded shrimp Stenopus hispidus (Reference 8 in Appendix 1, Table 10), the<br />

scarlet cleaner shrimp Lysmata debelius (Reference 12 in Appendix 1, Table 10), and the harlequin<br />

shrimp Hymenocera picta (Reference 16 in Appendix 1, Table 10).<br />

Detailed observations of the monogamous nature of pairing have been made for several species<br />

of snapping shrimps, for example, Alpheus angulatus (Reference 97 in Appendix 1, Table 9),<br />

Alpheus heterochaelis (Reference 99 in Appendix 1, Table 9), Alpheus armatus (Reference 28 in<br />

Appendix 1, Table 9), and Alpheus roquensis (Reference 31 in Appendix 1, Table 9), as well as for<br />

the pontoniid shrimp Pontonia margarita (Reference 45 in Appendix 1, Table 8), the deep-water<br />

sponge-dwelling shrimp Spongicola japonica (Reference 1 in Appendix 1, Table 10), a porcelain<br />

crab Poly onyx gibbesi (Reference 11 in Appendix 1, Table 11), and several species of coral crabs<br />

of the genus Trapezia (References 2-14 in Appendix 1, Table 12). Many pair-bonding species are<br />

known in caridean shrimps of the subfamily Pontoniinae and family Alpheidae, "cleaner" shrimps<br />

of the families Stenopodidae and Spongicolidae, crab-shaped anomurans (family Porcellanidae),<br />

and brachyuran crabs of the family Trapeziidae.<br />

Most of these species are symbiotic with other animals or live in special habitats. Host animals<br />

for these species include sponges, sea anemones, black corals, reef-building corals, gastropods,<br />

opistobranch molluscs, bivalves, polychaetes, crinoid feather stars, sea stars, sea urchins, sea cucumbers,<br />

and ascidians. The special habitats include gastropod shells used by large hermit crabs; tubes<br />

of polychaetes such as Chaetopterus; soft, web-like tubes consisting of filamentous algae, sponges,<br />

and other debris built by shrimp themselves; burrows excavated in hard dead corals; burrows of gobiid<br />

fish; and burrows of the thalassinidean shrimp genus Upogebia. However, free-living species are<br />

also known, such as stenopodid shrimps inhabiting rocky subtidal zones and many alpheid shrimp<br />

species inhabiting rock crevices or found under rubble, around large algae, or in burrows of their<br />

own in mudflats and other soft bottoms.<br />

The following generalizations can be made for almost all of these species. They are territorial,<br />

and they cooperatively defend their habitats (hosts, special habitats, and burrows) against other conspecific<br />

or non-conspecific animals. Thus, the mating system of these species is termed "resourcedefense<br />

monogamy." The pairs are size-matched (— size-assortative pairing); there is strict preference<br />

exerted by either sex for mates of a particular size relative to themselves. Baeza (2008) proposed<br />

two possible explanations for this phenomenon in his study on pontoniid shrimps symbiotic<br />

with bivalves:<br />

1. The two sexes might choose large individuals of the opposite sex as sexual partners and host<br />

companions. In males, a preference for large females should be adaptive, as female size is<br />

positively correlated with fecundity in shrimps. In females, sharing a host with a large male<br />

might result in indirect benefits (i.e., good genes) or direct benefits (increased protection<br />

against predators or competitors).<br />

2. Choice of a certain-size partner could also be a consequence of constraints in the growth rates<br />

of shrimps dictated by host individuals. Space limitations for shrimps in hosts are suggested<br />

by the tight relationship between shrimp and host size, and by the fact that hosts harboring<br />

solitary or no shrimps were among the small hosts.

128 Asakura<br />

These species tend to display low sexual dimorphism in weaponry in terms of cheliped size and morphology<br />

and often in body size. This is in contrast to the large sexual differences in mate-guarding<br />

species in which the weaponry is much more developed and where body size is often much larger<br />

in males than in females. Regarding body size, there is a tendency in pair-bonding shrimp for the<br />

male to be slightly smaller, in terms of body length, and much more slender than its mate female;<br />

in trapeziid crabs the male is often slightly larger than his female mate.<br />

The bathymetric distribution of species with this mating system is generally from intertidal to<br />

shallow water, but a few groups of species, such as those of the Spongicolidae, inhabit deep water.<br />

3.5 Eusociality type<br />

Until the discovery of the eusocial shrimp Zuzalpheus regalis (as Synalpheus regalis) (Duffy 1996),<br />

eusociality was recognized only among social insects, including ants, bees, and wasps (Hymenoptera)<br />

and termites (Isoptera); in gall-making aphids (Hemiptera); in thrips (Thysanoptera); and in<br />

two mammal species, the naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) and the damaraland mole rat<br />

(Cryptomys damarensis). Zuzalpheus regalis lives inside large sponges in colonies of up to >300<br />

individuals, with each colony containing a single reproductive female. Direct-developing juveniles<br />

remain in the natal sponge, and allozyme data indicate that most colony members are full siblings.<br />

Larger members of the colony, most of whom apparently never breed, defend the colony against<br />

heterospecific intruders (Duffy 1996).<br />

Following this initial discovery, Duffy and his coworkers have found several other species<br />

of Zuzalpheus exhibiting monogynous, eusocial colony organization in the western Atlantic<br />

(Appendix 1, Table 13). In the Indo-west Pacific region, Didderen et al. (2006) found a colony<br />

of a sponge-dwelling alpheid shrimp, Synalpheus neptunus neptunus, with one large ovigerous female<br />

or "queen" together with many small individuals, indicating a eusocial colony organization<br />

(Appendix 1, Table 13).<br />

Some 20 species of symbiotic decapod species have been reported as found in a group<br />

(Appendix 1, Tables 14-15). Among them, examples of Synalpheus and Zuzalpheus exhibited more<br />

than 100 individuals in one aggregation, and, in particular in the case of Zuzalpheus brooksi, more<br />

than 1000 individuals were recorded from one sponge. These aggregations are regarded either as<br />

having a non-social structure (Thiel & Baeza 2001) or with the social structure totally unknown.<br />

3.6 Waving display type<br />

In many species of the crab families Ocypodidae, Dotillidae, and Macrophthalmidae, and in species<br />

of the genus Metaplax of the family Varunidae (formerly subfamily Varuninae in the Grapsidae<br />

sensu lato), males perform waving displays using the chelipeds. As in many other territory advertisement<br />

signals in animals, this behavior is commonly thought to have the dual function of simultaneously,<br />

repelling males and attracting females (e.g., Salmon 1987; Crane 1975). These species<br />

typically live in mudflats, tidal creeks, sandbars, and mangrove forests, and each individual has its<br />

own burrow with a small territory around it. They often occur in huge numbers, with thousands of<br />

individuals living in small, adjacent territories, and with males and females living intermixed. The<br />

burrow serves various functions, including a refuge during high tide, an escape from predators, and<br />

the site of mating, oviposition, and incubation.<br />

The behavior and mating systems of fiddler crabs (genus Uca, Ocypodidae) have been intensively<br />

studied (see references in History of Study, above). There are species whose males defend<br />

burrows from which they court females and species whose males wander from their burrows and<br />

court females on the surface (Christy 1987). For the former group of species, the following generalization<br />

is possible (based mainly on P. Backwell and coworkers; see references in History of Study,<br />

above). Males wave their enlarged claw, and, when a female is ready to mate (i.e., she matures),<br />

she leaves her own burrow and wanders through the population of waving males. The female visits

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 129<br />

several males before selecting a mate, and a visit consists of a direct approach to the male. Before<br />

copulation^ both individuals enter the male's burrow, and two behavioral patterns are known: the<br />

male enters his burrow first and the female follows him in, or it happens in the reverse order, i.e.,<br />

the female enters first. The male then gathers up sand or mud to plug the burrow entrance. Mating<br />

occurs in the burrow. On the following day, the male emerges, reseals the burrow entrance with the<br />

female still underground, and leaves the area. The female remains underground for the following<br />

few weeks while she incubates her eggs.<br />

In addition to waving displays, males of some fiddler crab species employ acoustic signals to<br />

attract females. In these species, males attract females during the day first by waving and then by<br />

producing sounds just within their burrows. At night, the males produce sounds at low rates, but<br />

when touched by a female they increase their rate of sound production (Salmon & Atsaides 1968).<br />

Many species of ocypodid crabs build sand structures next to their burrows, some of which function<br />

to attract females for mating, such as pillars (Uca: Christy 1988a, b), hoods (Uca: Zucker 1974,<br />

1981; Christy et al. 2002, 2003a, b), mudballs (Uca: Oliveira et al. 1998), and pyramids (Ocypode:<br />

Linsenmair 1967; Hughes 1973).<br />

3.7 Visiting type<br />

An interesting mating system has been suggested for coral gall crabs (family Cryptochiridae), which<br />

inhabit cavities in scleractinian corals in (usually) shallow water. However, the information is still<br />

anecdotal, based on ecological observations on Hapalocarcinus marsupialis, Troglocarcinus corallicola,<br />

and Opecarcinus hypostegus (Potts 1915; Fize 1956; Kropp & Manning 1987; Takeda &<br />

Tamura 1981; Hiro 1937; Kotb & Hartnoll 2002; Carricart-Ganivet et al. 2004). In H. marsupialis<br />

and T. corallicola, the male crab normally resides outside the gall, which was constructed by the<br />

female, and is thought to visit the gall of the female for mating. The males and females apparently<br />

show promiscuity, and male-male aggressive behavior for a female has not been reported. The female<br />

is much larger than the male and in some species has a soft body with a very large abdomen. On<br />

thfe other hand, the male is usually hard, with a small abdomen. Geographical distribution includes<br />

mostly the tropics (see Wetzer et al. this volume).<br />

In Opecarcinus hypostegus, couples were found sharing cavities; ovigerous females and males<br />

are recorded inhabiting adjoining cavities on colonies of Siderastrea stellata corals (Carricart-<br />

Ganivet et al. 2004). This species may have a mating system different from the above.<br />

3.8 Reproductive swarm type<br />

This mating system is reported only in pinnotherid crabs that are considered parasitic or co-inhabiting<br />

with other animals, including bivalves, gastropods, sea slugs, chitons, polychaetes, echinoderms,<br />

burrowing crustaceans, and sea squirts (Cheng 1967; Gotto 1969). In several species of these crabs,<br />

mating occurs, or is thought to occur, when the female is in the free-swimming stage before she<br />

enters into her definitive host (Appendix 1, Table 16).<br />

The following generalization is possible for these species. Adult females have a soft, membranous<br />

carapace, and generally each one lives by itself within its host animal. These females produce<br />

broods of planktonic larvae. After development, the larvae metamorphose into the "invasive stage"<br />

crab, which is morphologically similar to the later swimming stage in having a flattened shape and<br />

ambulatory legs with dense setae adapted for swimming. Following this stage is a stage designated<br />

as "prehard"; these crabs invade, and live in, the host invertebrate animals. The crab at this stage<br />

is soft, resembling the later posthard stage. These crabs grow and mature into small adults of both<br />

sexes and leave their host to join mating swarms in open water. This stage is called the "hard stage,"<br />

swimming stage, or copulation stage, and it is characterized by a hard body, swimming legs densely<br />

fringed with setae, and a thick fringe of setae along the front of the carapace. They copulate at<br />

this stage, and, in all reported species (see Appendix 1, Table 16), females copulate in the hard

130 Asakura<br />

shell condition. After copulation, each female enters the host animal, but the male dies. The female<br />

becomes soft and grows much larger in the host, and later the female produces eggs fertilized by<br />

sperm from her single mating.<br />

This is a kind of mass mating, with males and females showing promiscuity. In the copulation<br />

stage, no intensive aggressive behavior between males for females has been reported. The males<br />

in this stage are slightly larger than the females, and the morphology is similar between the sexes.<br />

After the female enters the host animal, the female becomes soft and grows much larger and stouter.<br />

The species with this mating system are found generally from intertidal to shallow water where their<br />

host invertebrates occur. In some pinnotherid species, adult crabs are found in a heterosexual pair in<br />

the host animal, although life history and mating systems of these species are mostly unknown.<br />

3.9 Neotenous male type<br />

Extremely small, neotenous males exist in some species of anomuran sand crabs (genus Emerita)<br />

inhabiting wave-exposed sandy beaches in tropical and temperate waters (Appendix 1, Table 17). In<br />

these species, the males become sexually mature soon after their arrival on the beach as a megalopa.<br />

When copulating, a male attaches near one of the female's gonopores, which are located on the<br />

coxae of the third pereopods. Surprisingly, the size of the neotenous males is similar to, or smaller<br />

than, those coxae.<br />

Protandric hermaphroditism is described in detail in Emerita asiatica as it relates to neotenous<br />

males (Subramoniam 1981). The neotenous males occur at 3.5 mm carapace length (CL) and above,<br />

whereas females acquire sexual maturity at 19 mm CL. The neotenous males, as they continue<br />

to grow, gradually lose male functions and reverse sex at about 19 mm CL. In the CL range of<br />

19-22 mm, the male's gonad consists of inactive testicular and active ovarian portions. Androgenic<br />

glands, active in the neotenous males, show signs of degeneration in the larger males and disappear<br />

in the intersexuals.<br />

The male separates from the female after copulation. Aggressive behavior between males is not<br />

reported. As opposed to the female, the neotenous male shows a general simplicity of appendages<br />

associated with its small size. Among decapods, this phenomenon is known only in species of<br />

Emerita.<br />

4 EVOLUTION OF MATING SYSTEMS IN DECAPODA<br />

4.1 Introduction<br />

It is apparent from the above that similar mating systems have evolved independently in different<br />

taxa at different times; i.e., convergent evolution is widespread. Species in ecologically similar<br />

habitats often display patterns that are strikingly comparable. Here I discuss the possible origin and<br />

evolutionary pathway of each mating system and compare them with those of other animals.<br />

4.2 Evolution of the short courtship type and the precopulatory type<br />

These two mating systems are most dominant among decapods. The mode of life is often quite<br />

similar; both males and females are free living (not symbiotic with other organisms), and after<br />

mating the male soon separates from the female. However, the habitat is sometimes different; in<br />

terrestrial and freshwater species, only the short courtship type has been reported. Therefore, a<br />

question arises as to why some groups of species have evolved the prolonged precopulatory mate<br />

guarding, whereas others have not.<br />

Precopulatory mate guarding is known in a very broad range of taxa such as tardigrades, crustaceans,<br />

arachnids, and anurans (Parker 1974; Ridley 1983; Conlan 1991). It is thought to evolve<br />

when male-male competition for females is strong enough and female receptivity is restricted in

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 131<br />

time (Parker 1974; Jormalainen 1998), or even if receptivity is not time-limited but the guarding<br />

costs are low enough (Yamamura 1987). Guarding should be beneficial to the male, if the expected<br />

fitness gain achieved by guarding is greater than that expected by continuing to search for other<br />

females (Parker 1974). Thus, the optimal guarding duration for the male is determined by the encounter<br />

rate of females and the costs of guarding relative to those of searching (Yamamura 1987).<br />

The cost of guarding for males includes decreased mobility and feeding (Adams et al. 1985, 1991;<br />

Robinson & Doyle 1985), an increase in predation risk while guarding (Verrel 1985; Ward 1986), increased<br />

energetic costs associated with carrying females (Sparkes et al. 1996; Plaistow et al. 2003),<br />

and an increase in fighting costs through male-male conflict (Benesh et al. 2007; Yamamura &<br />

Jormalainen 1996). Additionally, a long guarding time decreases future opportunities to mate with<br />

other females (Benesh et al. 2007).<br />

Pelagic dendrobranchiate and caridean shrimps are primarily swimmers, and possibly for that<br />

reason they have not evolved prolonged, elaborate behavioral interactions before copulation. However,<br />

the above-mentioned energetic cost hypothesis (Sparkes et al. 1996; Plaistow et al. 2003) may<br />

be applicable; for males of these species, carrying a swimming female for a long duration requires<br />

much more energy than in benthic species. In fact, all species exhibiting a prolonged precoulatory<br />

guarding period are benthic species.<br />

In all freshwater crayfish studied, the mating system includes a short courtship without a lengthy<br />

precopulatory guarding, even though they have a benthic lifestyle and male-male aggression is<br />

often common. They may live in their burrows separately, or underneath boulders or heaps of fallen<br />

leaves, and these habitats are quite similar to, or virtually the same as, those of shrimps of the genus<br />

Macrobrachium. Why males of Macrobrachium adopt a precopulatory guarding strategy whereas<br />

male crayfish do not is not known.<br />

A similar question arises in intertidal and shallow water decapods. For example, intertidal hermit<br />

crab species exhibiting precopulatory guarding have a tendency toward vastly unequal chelipeds,<br />

with a well-developed major cheliped particularly in males, who use it for fighting with<br />

olher males during guarding. Such species include those of the genera Pagurus (Paguridae) and<br />

Dmgenes (Diogenidae). On the other hand, species of Paguristes have small and similar right and<br />

left chelipeds and execute short courtship mating; males do not aggressively fight with other males.<br />

Species of Calcinus, which conduct short courtship type mating, often have vastly unequal chelipeds,<br />

with the well-developed major cheliped similar to those species that display precopulatory<br />

guarding. However, males of Calcinus species do not aggressively fight with each other during mating.<br />

Further study is needed to clarify the relationship between mating behavior and morphology.<br />

In land hermits and land brachyurans, the above-mentioned predation risk hypothesis (Verrel<br />

1985; Ward 1986) may be applicable to those species where mating system is the short-courtship<br />

type with hard-female mating. Male-male aggression is common in these taxa, but they have never<br />

evolved precopulatory guarding. Prolonged guarding may carry the risk of attack by visual predators<br />

such as birds in a terrestrial environment. In these taxa, a strong connection exists between a<br />

prolonged precopulatory guarding and soft-female mating as well as between a short courtship and<br />

hard-female mating. When marine species adapted to land, the former mating system might have<br />

been lost and changed to the latter, i.e., from soft-female to hard-female, to avoid desiccation and<br />

to deal with the large and often unpredicted fluctuations in availabilities of females in a terrestrial<br />

environment.<br />

The evolution of sperm plugs in species of short-courtship type (penaeid shrimps) and precopulatory<br />

type (brachyuran crabs) is interesting. The sperm plug has virtually the same function as<br />

the copulation plug (= copulatory plug, mating plug) in mammals (rodents, bats, monkeys, koala),<br />

reptiles (snakes and lizards), insects (butterflies, ants, dragonflies, and stinkbugs), spiders, and acanthocephalan<br />

worms (Smith 1984). These plugs, secreted by the male after mating, serve to block the<br />

female tract for some time to prevent further mating by other males.

132 Asakura<br />

4.3 Evolution of the podding type<br />

Why many animal species (e.g., insects, fish, birds, and herbivorous mammals) group together is<br />

one of the most fundamental questions in evolutionary ecology. It is believed that strong selective<br />

pressures lead to aggregation rather than to a solitary existence in most of these groups. These pressures<br />

include protection against predators, increased foraging efficiency, increased ease of assessing<br />

potential mates, and increased information exchange about the location of food (Barta & Giraldeau<br />

2001). Similarly, various ecological reasons for the formation of pods have been proposed, including<br />

protection during molting, location of mates, aiding in food capture, and protection from predation<br />

(see References in Appendix 1, Table 7). Why some species evolved aggregating behavior and others<br />

did not is unknown.<br />

4.4 Evolution of the pair-bonding type<br />

Heterosexual pairing behavior ("social monogamy," Gowaty 1996; Bull et al. 1998; Gillette et al.<br />

2000; Wickler & Seibt 1981) has evolved many times in a broad range of animal taxa, including<br />

mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects, and crustaceans. For example, a colony of<br />

scleractinian coral sometimes yields a pair of goby fish, alpheid shrimps, and trapeziid crabs. Researchers<br />

interested in social system evolution must look for ecological and physiological factors<br />

(beyond basic sexual differences) that may make social monogamy selectively advantageous to individual<br />

males and/or females. Of particular interest are factors that may consistently correlate with<br />

such behavior across taxonomic groups. Several hypotheses for the evolution of social monogamy<br />

have been developed [see also Mathews (2002b), Baeza (2008), Baeza & Thiel (2007) for a review],<br />

as follows.<br />

Biparental care hypothesis: Kleiman (1977) argued that the advantages of monogamy in mammals<br />

can lead to social monogamy. The hypothesis also implies that both males and females would<br />

suffer significantly reduced or zero fitness if they did not cooperate in caring for the offspring. However,<br />

this is not the case for marine decapods, where only the females care for the fertilized eggs<br />

and where neither parent cares for the larvae.<br />

Extended mate guarding hypothesis: If males are under selection to guard females for some<br />

time before, during, and/or after courtship and mating, they may be forced into partner-exclusive<br />

behavior by some other factor, such as female dispersion (Kleiman 1977; Wickler & Seibt 1981)<br />

or female-female aggression (Wittenberger & Tilson 1980). In other words, monogamy can result<br />

from males guarding females over one or multiple reproductive cycles, because the female's synchronous<br />

receptivity, density, or abundance relative to males renders other male mating strategies<br />

(pure searching) less successful (Parker 1970; Grafen & Ridley 1983).<br />

Territorial cooperation hypothesis: The fact that most monogamous species are territorial leads<br />

to this hypothesis. Territoriality correlates in various ways with social system evolution (Emlen &<br />

Oring 1977; Hixon 1987), and cooperation in territorial defense can lead to individual advantages<br />

in social groups or pairs (Brown 1982; Davies & Houston 1984; Fricke 1986; Clifton 1989, 1990;<br />

Farabaugh et al. 1992). In other words, males and females benefit by sharing a refuge (a territory)<br />

as heterosexual pairs because, for example, the risk of being evicted from the territory by intruders<br />

decreases (Wickler & Seibt 1981).<br />

Recent intensive behavioral studies in various species shrimps have supported the predictions of<br />

the mate-guarding and/or territorial cooperation hypotheses (e.g., in Hymenocera picta, Wickler &<br />

Seibt 1981; Alpheus angulatus, Mathews 2002a, b, 2003; and Alpheus heterochelis, Rahman et al.<br />

2002,2003).<br />

Another hypothesis about social monogamy (Baeza & Thiel 2007) concerns species symbiotic<br />

to other organisms (= host). Baeza & Thiel predicted that monogamy evolved when hosts are<br />

small enough to support few individuals and are relatively rare, and when predation risk away<br />

from the hosts is high. Under these circumstances, movements among hosts are constrained, and

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 133<br />

monopolization of hosts is favored in males and females due to their scarcity and because of the<br />

host's value in offering protection against predators. Because spatial constraints allow only a few<br />

adult symbiotic individuals to cohabit in/on the same host, both adult males and females would<br />

maximize their reproductive success by sharing "their" dwelling with a member of the opposite sex.<br />

This hypothesis was supported by Baeza's (2008) intensive study on a heterosexual pair of Pontonia<br />

margarita, a species symbiotic to the pearl oyster.<br />

However, as mentioned before, most of observations for this mating system are anecdotal,<br />

and further detailed study is needed to clarify actual conditions of monogamous features of those<br />

species.<br />

4.5 Evolution of the eusocial type<br />

Hypotheses explaining how eusociality has evolved include Trophallaxis Theory (Roubaud 1916),<br />

Parental Manipulation Theory (Michener & Brothers 1974), Superorganism Theory (Reeve &<br />

Holldobler 2007), and Inclusive Fitness Theory (Hamilton 1964a, b), of which the last one is most<br />

widely accepted. According to the Inclusive Fitness Theory, eusociality may evolve more easily in<br />

species exhibiting haplodiploidy, which facilitates the operation of kin selection. Although eusocial<br />

mole rats and termites exhibit diploidy, they display high levels of inbreeding by living as a family<br />

in a single burrow, such that colony members share more than 50% of their genes, and therefore<br />

the same model is considered to apply to these species and also to eusocial Zuzalpheus shrimps, in<br />

which all members of a colony share a single sponge.<br />

4.6 Evolution of the waving display type<br />

As compared to terrestrial species, courtship in aquatic species may be short and may not involve<br />

elaborate visual signaling (display) by the males; in aquatic species, chemical or visual cues are<br />

more important stimuli. In species of several genera of semi-terrestrial (-upper intertidal) decapods<br />

including Uca and other ocypodid crabs, visual signalling for prolonged periods is common, and<br />

sounds are often emitted by males to "call" females from their burrows to the surface for mating.<br />

Salmon •& Atsaides (1968) presented ecological arguments to account for these differences in terms<br />

of optimal strategy of distance communications in the terrestrial and aquatic environments. Most<br />

aquatic decapods are nocturnally active and cryptic and live in an acoustically noisy environment,<br />

and this situation virtually eliminates all but the chemical channel for effective distance communication.<br />

On the other hand, visual and acoustic signals are effective in terrestrial species and are well<br />

developed in most terrestrial animals such as insects, birds, mammals, and also ocypodid and other<br />

terrestrial and semi-terrestrial decapods, probably because of the greater visibility in the terrestrial<br />

environment.<br />

Waving displays seen in a variety of semi-terrestrial crabs is a case of convergent evolution<br />

(Kitaura et al. 2002). Grapsid crabs of the genus Metaplax conduct waving displays like species<br />

of the ocypodid crab genera Uca, Macrophthalmus, Scopimera, and Dottila (Kitaura et al. 2002).<br />

Species of Metaplax, unlike other grapsid crabs, which generally live along rocky shores, live in<br />

mud flats and burrow into the mud like many ocypodids. Salmon & Atsaides (1968) proposed the<br />

following factors as advantageous for the evolution of visual signaling in semi-terrestrial crabs: the<br />

substrate, which is flat and relatively free from the vegetational obstructions and other discontinuities;<br />

diurnal activity of the crabs; and the feeding proximity to their shelters, which leads crabs<br />

to live in aggregations so that social contacts are frequent. Therefore, it is assumed that habitat<br />

similarity between Metaplax and ocypodid crabs resulted in convergent evolution of these displays.<br />

A recent molecular phylogenetic analysis suggested that even the waving display in Uca has<br />

multiple origins (Sturmbauer et al. 1996). Indo-west Pacific Uca species have simpler reproductive<br />

social behaviors, are more marine, and were thought to be ancestral to the behaviorally more complex<br />

and more terrestrial American species. It was also thought that the evolution of more complex

134 Asakura<br />

social and reproductive behavior was associated with the colonization of the higher intertidal zones.<br />

However, Sturmbauer et al. (1996) demonstrated that species bearing the set of "derived traits" are<br />

phylogenetically ancestral, suggesting an alternative evolutionary scenario: the evolution of reproductive<br />

behavioral complexity in fiddler crabs may have arisen multiple times during their evolution,<br />

possibly by co-opting of a series of other adaptations for high intertidal living and antipredator<br />

escape.<br />

This mating system is quite similar to male-territory-visiting polygamy (Kuwamura 1996) in<br />

fish, in which many examples are known in intertidal or shallow species; males have a burrow or a<br />

territory, and, when a mature female approaches a male, the male changes the color of part of his<br />

body and/or conducts species-specific courtship displays, after which the female enters the burrow<br />

or territory of the male and spawns (e.g., Miyano et al. 2006). In these fish species, males are brilliantly<br />

colored, as are male Uca species.<br />

4.7 Evolution of the visiting type<br />

A widely recognized tendency among various kinds of animals is that females live in a particular<br />

place and have a narrow home range, whereas males have a comparatively wider home range<br />

(Clutton-Brock et al. 1982). This "visiting type" mating system (seen in cryptochirid crabs) probably<br />

has evolved as one extremity of this tendency, with females living in a very specialized habitat<br />

(inside coral galls).<br />

4.8 Evolution of the reproductive swarm type<br />

Surprisingly, the function of the reproductive swarm in pinnotherid crabs is very similar to that of<br />

the nuptial flight (mating swarm) in ants (Insecta, Formicidae), and indeed their life history is quite<br />

similar. In most species of ants, breeding females and males that mature in their mothers' nest have<br />

wings and, during the breeding season, fly away from their nests and form swarms. Mating occurs<br />

during this period, and the males die shortly afterward. The surviving females land, and each female<br />

digs a burrow for the new nest. As eggs are laid in the burrow, stored sperm, obtained during their<br />

single nuptial flight, is used to fertilize all future eggs produced.<br />

In the pinnotherids, crabs first grow in their host animals (vs. ants in their initial burrow). Then<br />

the crabs with swimming setae leave the hosts and swarm (vs. ants with wings fly away from their<br />

nests and conduct the nuptial flight). Mating occurs during this period (in ants, too), after which the<br />

female crabs enter the hosts, whereas the males die just after the mating (vs. the female ants make<br />

burrows of their own, with males dying just after the mating). As in the case of the ants, the female<br />

crabs reproduce by fertilizing their eggs with sperm from a single mating.<br />

4.9 Evolution of the neotenous male type<br />

The miniaturization of male mole crabs in the anomuran genus Emerita coupled with neoteny is<br />

similar to "dwarf males" (parasitic males, complemental males, miniature males), which are tiny<br />

males often attached to females. This condition has evolved in various groups of animals, including<br />

thoracican barnacles (Yamaguchi et al. 2007), acrothoracican barnacles (Kolbasov 2002), the oyster<br />

Ostreapuelchanas (Castro & Lucas 1987; Pascual 1997), epicaridean isopods (Mizoguchi et al.<br />

2002), an echiuran Bonellia (Berec et al. 2005), anglerfish (Lophiiformes) (Pietsch 2005), blanket<br />

octopus (Tremoctopodidae), argonauts (Argonautidae), football octopus (Ocythoidae), and a deeper<br />

water octopus Haliphron atlanticus (Alloposidae) (Norman et al. 2002). The evolutionary cause for<br />

these phenomena has not been fully studied. The neoteny of male Emerita is considered to be one<br />

rather radical evolutionary solution to the problem of keeping the male and female together in the<br />

harsh and turbulent surf zone environment (Salmon 1983; Subramoniam & Gunamalai 2003).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS<br />

The Evolution of Mating Systems in <strong>Decapod</strong> <strong>Crustacean</strong>s 135<br />

I am deeply grateful to Joel W. Martin (<strong>Natural</strong> History Museum of Los Angeles County, U.S.A.)<br />

for giving me the opportunity to present my work at the symposium on decapod phylogenetics at<br />

the TCS Winter Meeting in San Antonio, Texas. Thanks are also due to the following persons who<br />

provided me with important literature or aided me in my bibliographical survey: Keiichi Nomura<br />

(Kushimoto Marine Park, Japan), Tomomi Saito (Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium), Annie Mercier<br />

(Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada), Juan P. Carricart-Ganivet (El Colegio de la Frontera<br />

Sur, Unidad Chetumal, Mexico), Jorge Contreras Gardufio (Entomologia Aplicada, Instituto<br />

de Ecologfa, Mexico), Ana Maria S. Pires-Vanin (Instituto Oceanografico, Universidade de Sao<br />

Paulo, Brazil), J. Antonio Baeza (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Republic of Panama),<br />

Martha Nizinski (NOAA/NMFS Systematics Laboratory, Smithsonian Institution, U.S.A.), Panwen<br />

Hsueh (National Chung Hsing University, Taiwan), Estela Anahi Delgado (Undecimar, Facultad<br />

de Ciencias, Uruguay), Michiya Kamio (Georgia State University, U.S.A.), Satoshi Wada<br />

(Hokkaido University, Japan), Yoichi Yusa (Nara Women's University, Japan), Tomoki Sunobe<br />

(Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology), Charles H. J. M. Fransen (Nationaal Natuurhistorisch<br />

Museum <strong>Natural</strong>is, The Netherlands), E. Gaten (University of Leicester, U.K.), Gil<br />

G. Rosenthal (Texas A&M University, U.S.A.), and Hiromi Watanabe (JAMSTEC, Japan). Special<br />

thanks are due to Raymond Bauer (University of Louisiana Lafayette) and Joel W. Martin for the<br />

careful review of an earlier draft of the manuscript.<br />

REFERENCES<br />

Adams, J., Edwards, A.J. & Emberton, H. 1985. Sexual size dimorphism and assortative mating<br />

in the obligate coral commensal Trapezia ferruginea Latreille (<strong>Decapod</strong>a, Xanthidae). <strong>Crustacean</strong>aAK:<br />

188-194.<br />

Adams, J., Greenwood, P., Pollitt, R. & Yonow, T. 1991. Loading constraints and sexual size dimor-<br />

, phism in Asellus aquaticus. Behaviour-92: 277'-287.<br />

Asakura, A. 1987. Population ecology of the sand-dwelling hermit crab, Diogenes nitidimanus<br />

Terao. 3. Mating system. Bull Mar. Sci. 41: 226-233.<br />

Asakura, A. 1990. Evolution of mating system in decapod crustaceans, with particular emphasis on<br />

recent advances in study on precopulatory guarding. Biol. Sci., Tokyo 42: 192-200.<br />

Asakura, A. 1993. Recent advances in study on aggressive and agonistic behavior of hermit crabs.<br />

I. General introduction and aggressive behavior. Biol. Sci., Tokyo 45: 143-160.<br />

Asakura, A. 1994. Recent advances in study on aggressive and agonistic behavior of hermit crabs.<br />

II. Shell fighting and evolution of ritualization. Biol. Sci, Tokyo 46: 102-112.<br />

Asakura, A. 1995. Sexual differences in life history and patterns of resource utilization by the hermit<br />

crab. Ecology 76: 2295-2313.<br />

Asakura, A. 1998a. Sociality in decapod crustaceans. I. Relationship between males and females in<br />

species found in pair. Biol. Sci., Tokyo 49: 228-242.<br />

Asakura, A. 1998b. Sociality in decapod crustaceans. II. Relationship between individuals in species<br />

found in group, symbiotic to other organisms. Biol Sci., Tokyo 50: 37-43.<br />

Asakura, A. 1999. Preliminary notes on classification of mating systems in decapod crustaceans.<br />

Aquabiol, Tokyo 125: 516-521.<br />

Asakura, A. 2001a. Sexual difference and intraspecific competition in hermit crabs (Crustacea:<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong>a: Anomura). I. Morphological aspects. Aquabiol, Tokyo 135: 398-403.<br />

Asakura, A. 2001b. Sexual difference and intraspecific competition in hermit crabs (Crustacea:<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong>a: Anomura). II. Difference in growth and survivorship patterns between the sexes.<br />

Aquabiol, Tokyo 135: 404-410.<br />

Asakura, A. 2001c. Sexual difference and intraspecific competition in hermit crabs (Crustacea:<br />

<strong>Decapod</strong>a: Anomura). II. Behavioral aspects. Aquabiol, Tokyo 137: 589-593.

136 Asakura<br />

Backwell, RR.Y, Christy, J.H., Telford S.R., Jennions, M.D. & Passmore, N.I. 2000. Dishonest<br />

signalling in a fiddler crab. Proc. Royal Soc. Ser. B 261: 719-724.<br />

Baeza, J.A. 2008. Social monogamy in the shrimp Pontonia margarita, & symbiont of Pinctada<br />

mazatlanica, off the Pacific coast of Panama. Mar. Biol. 153: 387-395.<br />

Baeza, J.A. & Thiel, M. 2003. Predicting territorial behavior in symbiotic crabs using host characteristics:<br />

a comparative study and proposal of a model. Mar. Biol. 142: 93-100.<br />

Baeza, J.A. & Thiel, M. 2007. The mating system of symbiotic crustaceans. A conceptual model<br />

based on optimality and ecological constraints. In: Duffy, J.E. & Thiel, M. (eds.), Evolutionary<br />

Ecology of Social and Sexual Systems: <strong>Crustacean</strong>s as Model Organisms'. 249-267. Texas:<br />

Oxford Univ. Press.<br />

Barta, Z. & Giraldeau, L.A. 2001. Breeding colonies as information centers: a reappraisal of<br />

information-based hypotheses using the producer-scrounger game. Behav. Ecol. 12: 121-127.<br />

Bauer, R.T. 2004. Remarkable shrimps: natural history and adaptations of the carideans. Norman:<br />

Univ. Oklahoma Press.<br />

Bauer, R.T. & Martin, J.W. (eds.) 1991. <strong>Crustacean</strong> Sexual Biology. New York: Columbia Univ.<br />

Press.<br />

Benesh, D., Valtonen, T. & Jormalainen, V. 2007. Reduced survival associated with precopulatory<br />

mate guarding in male Asellus aquaticus (Isopoda). Ann. Zool. Fennici 44: 425-434.<br />

Berec, L., Schembri, P.J. & Boukal, D.S. 2005. Sex determination in Bonellia viridis (Echiura:<br />

Bonelliidae): population dynamics and evolution. Oikos 108: 473-484.<br />

Brown, J.L. 1982. Optimal group size in territorial animals. J. Theor. Biol. 95: 793-810.<br />

Bull, CM., Cooper, S.J.B. & Baghurst, B.C. 1998. Social monogamy and extra-pair fertilization in<br />

an Australian lizard, Tiliqua rugosa. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 44: 63-72.<br />

Cardenas, C.A., Canete, J., Oyarzun, S. & Mansilla, A. 2007. Agregaciones de juveniles de centolla<br />

Lithodes santolla (Molina, 1782) (Crustacea) en asociacion con discos de fijacion de Macrocystispyrifera<br />

(Linnaeus) C. Agardh, 1980. Investig. Mar., Mayo. 35: 105-110.<br />

Carlisle, D.B. 1957. On the hormonal inhibition of moulting in decapod Crustacea. II. The terminal<br />

anecdysis in crabs. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. U.K. 36: 291-307.<br />

Carricart-Ganivet, J.P., Carrera-Parra, L.F., Quan-Young, L.I. & Garcia-Madrigal, M.S. 2004. Ecological<br />

note on Troglocarcinus corallicola (Brachyura: Cryptochiridae) living in symbiosis with<br />

Manicina areolata (Cnidaria: Scleractinia) in the Mexican Caribbean. Coral Reefs 23: 215-217.<br />

Castro, N.F. & Lucas, A. 1987. Variability of the frequency of male neoteny in Ostrea puelchana<br />

(Mollusca: Bivalvia). Mar. Biol. 96: 359-365.<br />