A Whole Century Later, The Marcel Duchamp Fountain is Still Shaking up the Art World

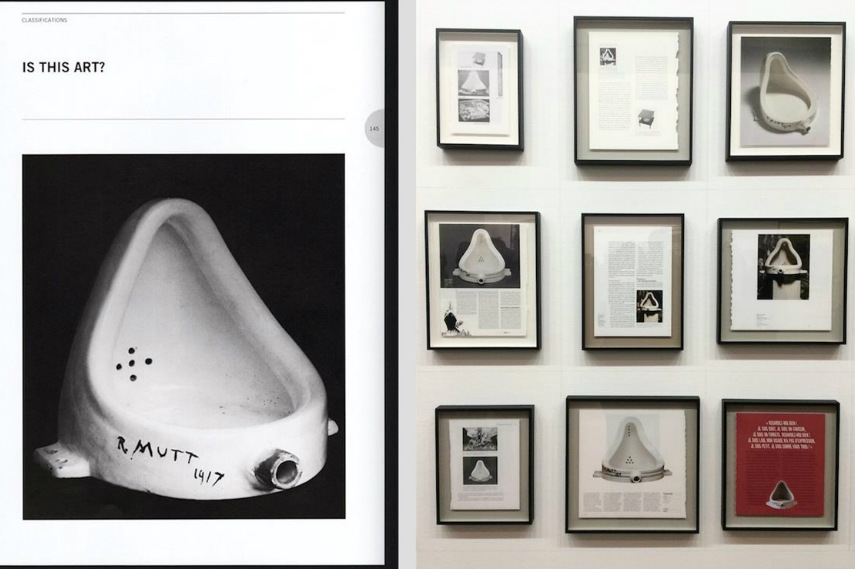

Exactly one hundred years ago, in 1917, the course of art history has been completely changed by a submission of a urinal signed "R. Mutt" for the exhibition of The Society of Independent Artists in New York – a work which we today know as The Duchamp Fountain.

Even though the idea of the exhibition was that every work submitted should be exhibited, and even though Marcel Duchamp himself was a part of the committee, The Fountain remained to be the only work, out of 2,125 others, that wasn't accepted for the exhibition.

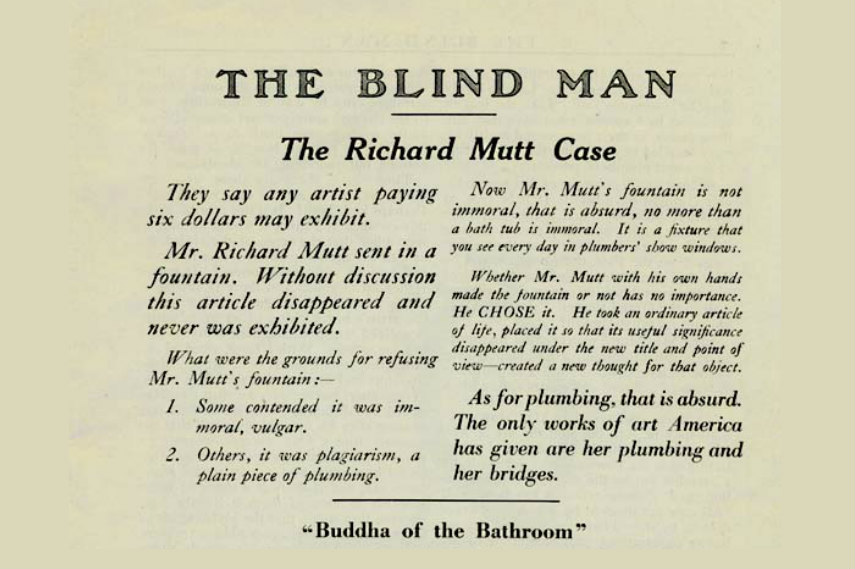

Duchamp's proxy, Beatrice Wood, published a defense of the work titled The Richard Mutt Case in the May edition of their Dada Journal, entitled The Blind Man.

Can One Make Modern Works That Are Not "Works" of Art?

This was a question asked by Duchamp in his notes from 1913, and it remains an essential one while considering the Richard Mutt Case.

As we can see, the work was not accepted because some members of the committee thought it was immoral and vulgar, and others did not even consider it to be art, but "a plain piece of plumbing" - since it did not involve any artistic work or production in its creation, and since it was just an ordinary mass-produced object.

This was a key moment for the development of the entire future of art, the moment in which art and life became completely intertwined, the moment in which the aesthetic questions about the value of paintings and sculptures stopped being central for art – but opened up space for new questions that are rather ontological ("What is Art?"), epistemological ("How can we know it?") and institutional ("Who determines it?")[1].

The Readymade Urinal of Marcel Duchamp - Art is Conceptual

The first Readymade was chosen by Duchamp in 1913, when a bicycle wheel and a kitchen stool become art just by the act of his nomination. This concept was important for him, since he criticized the retinal art that has been flourishing until that moment; art that, by his words, possesses only visual aesthetic value[2], and doesn't interest him at all.

This is why he decided to choose objects that he is completely indifferent about, that he finds no aesthetic value in, that he doesn't either like or dislike; objects that are not art, but ones that provoke you to think about something invisible as a value – the new Idea of them, when they are taken out of an everyday life context and placed into a new one.

This was a completely new concept at that moment, since he didn't want these innovations to be viewed as sculptures, he just wanted them to be what they are – readymades, utilitarian objects which lose their function and become art, just by the act of artistic nomination. He made only 13 readymades in his life to avoid the trap of falling into repetition. As he says in the art film about his life and ideas from 1963, Jeu d'echec avec Marcel Duchamp, "Repetition is the opposite of renewal. So it's a form of death."

It is also important that the readymades never become objects of like or dislike, and that the viewer manages to keep the ultimate distance from their aesthetic value as retinal art objects. The idea was that they remain being Objects, distanced from the viewer empirically, making sure that the eye never becomes the main organ for judgment.

The point was to create a relation towards the objects in a transcendental way, through thinking about the idea of them, of what they are when they are not a part of the consumerist culture, of what they mean when they stop being utilitarian.

Marcel Duchamp interview on Art and Dada (1956)

Duchamp's Autonomy of Art

Since the period of Enlightement, the idea of art autonomy has been present in philosophical works, especially in "The Critique of Judgment" by Immanuel Kant, who proclaimed that art has its own purposiveness without purpose, that art is useless if we want to consume it as a utilitarian product of our everyday life, but that its own purpose is in the fact that it gets created, a fact which guarantees its autonomy.

Following this idea, and radicalizing it in terms of turning art into something that doesn't even have to get created by an artist, but just nominated, Duchamp finally took a step that liberated art from having to be a craft, or an aesthetic pleasure for our eyes, or something that holds moral value, or something that looks different from our everyday life.[3]

Everyday life and art now became aesthetically identical, but the thought about them is what made the most important distinction; the thought which, in everyday life, ends with the ideas that we want to use an item for fulfilling a certain task, and the thought which can fly freely and associate new ideas to the given item when we present it as an artwork, it's ideas which actually become its artistic value.

This is exactly what gave birth to conceptual art which developed further in the 20th century.

Since Duchamp was working on the readymades during the Dada period, they also became one of the most representative jokes of this movement which disregarded all authority, value and ideas about the reality and art that existed before, a movement which started as a protest against the World War I and became the most liberating movement of the 20th century.[4]

It only seemed to be destructive in its core, but its destruction of previous ideas and values only created the potential of liberation for all artists who came afterward to think about art differently, and most importantly, to create their art freely.

An Influence on Conceptual Art

The most obvious influence of Duchamp's Fountain has been on the development of conceptual art, one in which ideas are more valued than the aesthetic quality of the works, art that often exposes items from everyday life and re-questions their meaning, as well as the meaning of the art as a medium itself.

One of the most representative early conceptual works, next to the Rauchenberg's Erased De Kooning Drawing from 1953 is definitely the installation One and Three Chairs by Joseph Kosuth, from 1965. The installation is composed out of a manufactured chair, its photograph, and its description as found in the dictionary.

Therefore, it raises the question of what is the most accurate representation of the chair, what gives it its meaning, and what is art, since none of the objects were produced by the artist himself. Again, we witness raising completely new issues about such a known everyday item, like a chair.

The 1917 Fountain Urinal - An Influence on Pop Art

We cannot mention the influence of Duchamp on the works of later artists without mentioning Pop art and Andy Warhol, who used the idea of readymades to make his sculptures, where he didn't take the objects themselves and name them as art, but made replicas of the consumerist products such as soap, juice or ketchup packages. In 1963 Warhol also took the famous intervention by Duchamp, Mona Lisa, and reinterpreted it by overexposing and multiplying it till the point where it loses significance and becomes just a repetitive, mass-produced object.

Based on Duchamp's idea that repetition is a form of death, this was a direct and bold criticism of the lifestyle brought in by capitalism and mass-production. Other pop-artists like Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake also created works inspired by Duchamp, and works that even involved his character as a core part of their expression.[5]

An Influence on Visual, Sound and Performance Art

Besides the obvious impact on the visual arts and the movements like Conceptual art, Pop art, Op art, Fluxus or Neo-dada, in 2013 The Barbican Art Gallery in London held an exhibition that questioned the impact of Duchamp on the development of the entire art history of the 20th century, which also included music, sound and dance.

It explored the work of Duchamp and its influence on four key modern avant-garde artists; composer John Cage, choreographer Merce Cunningham, and visual artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. They were all brought to presence, in this very anti-art-historical exhibition, by contemporary artist Philippe Parreno who connected their work within a mise en scène installation. The exhibition was about witnessing the inner connection between the concepts of these artists, the connection that was brought to life by a performance, instead of being examined trough a typical chronological setup.

This connection initially was about life; the means in which Duchamp took everyday objects and turned them into art by actually having a typical artwork absent and just the idea present and the approach of John Cage who made silence, the absence of sound, and everyday noises become art, followed by that action of Cunningham where he incorporated everyday movement of pedestrians into his choreography and used the effect of chance, such as throwing dice as means of determining the number of dancers he wants to use in a performance.

The curator's idea that brings together all of them trough performance, both to each other and to Duchamp who opened up space for it – might also be considered as a Fluxus idea, the one by Kaprow, where there has to be an end to the distinction between different types of art, where all art is one, and has to be interconnected both to different art techniques and to the approach to living our life, every day. Even Duchamp, in his interview for BBC from 1968. mentions how he enjoys Fluxus happenings, and how the audience accepted the idea of going somewhere to witness everyday life as art, and become "willingly bored" instead of amused.

Happenings were the predecessors to performance art which started flourishing in the 1960s art and is one of the key movements in contemporary arts today, with leading artists such as Marina Abramović who are still working on constantly pushing its boundaries.

The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns, Barbican Art Gallery, London

Celebrating One Hundred Years of The Marcel Duchamp Fountain 1917 - 2017

Using the words from Joseph Kosuth's influential text in 1969, Art After Philosophy, we can conclude that Duchamp has "given art its own identity, and with the unassisted Readymade art has changed its focus from the form of language to what is being said."

Artists and curators all over the planet are celebrating 100th anniversary of the Fountain by creating exhibitions that question the impact of this idea on the whole art scene, and by creating artworks that respond to the ontological questions about art which were raised by Duchamp. And even though it would be impossible to actually write everything about Duchamp's references and influences on a whole century of art in a single article, there are curators and galleries which are actually trying to collect all of the evidence in a single exhibition.

One of the most interesting responses to the anniversary is in Centre Pompidou in Paris, which opened on Monday, January 30, 2017., and aims to trace the diffusion of the "Fountain" over a century. The French conceptual artist Saâdane Afif aims to collect 1001 reproductions of Duchamp's Fountain by the end of 2017, which he has been collecting since 2008. Because his collection grew so popular and attracted the attention of publishers, he also started collecting print references to his own project, called Augmented.[6] This collection doesn't only try to find as many of the reproductions of the Fountain, but also questions its impact on different art movements, as well as the approach to the concept of reference which has been changing over a period of a century.

Is The Popularity of The Fountain Readymade Actually Opposed to The Initial Idea Of It?

If we don’t just pay attention to the influences this work had on the development of art, but trace its market value, popularization, publication in magazines where it’s being admired as if it was a sculpture, and the mass reproduction of it raised as a question by the mentioned artist Saâdane Afif, could we say that the piece was actually not properly understood by the public? And how can any kind of Dada art, which wanted to abolish the museums and get back to the streets and life, be properly exhibited inside a museum or a gallery, or admired by the audience?

Was this joke, hoax, work if art; however we call it, taken as a catalyst of change in a certain moment in time, which just opened up space for new styles of art to emerge, but didn't change much in terms of glorification of art and the artist, in the connection between art and life even in this case, where the object itself did belong to life, but moved far away from it because of its mass admiration and reproduction, which stands as the opposite of renewal and is "anti-life", by Duchamp's words?

Is there space for something truly Dada in art today, is there space for a shock, for abolishing the art-consumerist tradition we have been so deeply involved with, for a true autonomy where art is both free to be whatever it wants to be, for its own purpose, and not for the purpose of profit? Maybe this time DADA will not be just about freedom in art, and its ontology, but about freedom in the ontology of the ways we relate to art, consume art and life itself.

Editors’ Tip: Some Aesthetic Decisions: A Centenary Celebration of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain

Some Aesthetic Decisions is an exhibition featuring works by artists that explore issues of beauty, value, and judgment. One hundred years ago, Dada artist Marcel Duchamp forever changed the nature of art by anonymously submitting Fountain in 1917, a porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt” as an artwork to the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The show organizers’ rejection of Fountain ignited a controversy that persists today about the definition of art and who gets to pass judgment.

Editors’ Tip: Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain: One Hundred Years Later

This book marks the centenary of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain by critically re-examining the established interpretation of the work. It introduces a new methodological approach to art-historical practice rooted in a revised understanding of Lacan, Freud and Slavoj Žižek. In weaving an alternative narrative, Kilroy shows us that not only has Fountain been fundamentally misunderstood but that this very misunderstanding is central to the work’s significance. The author brings together Duchamp’s own statements to argue Fountain’s verdict was strategically stage-managed by the artist in order to expose the underlying logic of its reception, what he terms ‘The Creative Act.’ This book will be of interest to a broad range of readers, including art historians, psychoanalysts, scholars and art enthusiasts interested in visual culture and ideological critique.

References:

- Charles Harrison, Paul J. Wood, Art in Theory 1900 - 2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Blackwell Publishing, 2002

- Michel Sanouillet, Elmer Peterson, The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp, Thames and Hudson London, MIT Press, 1975

- Joseph Kosuth, Art After Philosophy and After: Collected Writings , MIT Press, 1991

- Joan Bakewell, Interview with Marcel Duchamp, BBC, 1968

- Jean-Marie Drot, Jeu d'echec avec Marcel Duchamp, Doriane Films, 1963

- Jackie Wullschlager, The Bride and the Bachelors: Duchamp with Cage, Cunningham, Rauschenberg and Johns, Barbican Art Gallery, Financial Times [February 23, 2017]

Featured Image: Marcel Duchamp - Fountain, 1917, Britannica. All images used for illustrative purposes only.

Can We Help?

Have a question or a technical issue? Want to learn more about our services to art dealers? Let us know and you'll hear from us within the next 24 hours.