Nothing readied me for the visual thunder, physical profundity, and oceanic joy of Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs at MoMA. In The Cut-Outs, Matisse found the artistic estuary he’d always been looking for, a way to concretize and make physical the painted flat space of his own early 20th-century invention, Fauvism — color used to describe form, its fatness, fullness, and where it’s located in space, while being almost abstract, voluptuously colored, radically simplified, or elaborated. With The Cut-Outs, Matisse crosses a mystical bridge. One of the true inventors of Modernism, he stands at the precipice and points to a way beyond it, to a pre-digitalized space, where pixels and separate segments of color and line form images, where painting seems to exist even where there is no paint and no canvas. With The Cut-Outs, Matisse goes beyond the romantic notion of the self-mythologizing agonized male genius. With The Cut-Outs, all we see is the work; only process is present; process and something as close to pure beauty in all of Western art.

Matisse made these works in a prolonged fever-dream that lasted from the early 1940s to the week he died in 1953, at the age of 84. Combining drawing, painted paper cut with scissors and shears, and pinning and pasting this tactile pliant material to flat surfaces, Matisse collapsed boundaries between painting, sculpture, drawing, architecture, bas-relief, pattern, decoration, and art. This is Matisse locked in tight. The Cut-Outs are a new form of poetry that come at us like a flotilla of visionary barges on an imaginary Nile.

Two giant, mural-like works in the show’s third gallery from 1946, Oceania, the Sky and Oceania, the Sea (both on loan from Paris for the first time ever), are just white paper on a wide expanse of raw canvas. Huge, minimal, monochromatic, and reduced to essentials, the works are so sensual, it’s like we’re looking at them with our kundalini. Flying fish fill empty skies, birds dive under invisible waters, surf splashes, seaweed and shells float along some primordial tide. Vantage points toggle from above the waters to below to inside this mystic sea. Continual perceptual shifts between micro and macro scales occur; pinholes and minute surface changes loom large; a pucker on paper takes on the presence of a sun spot; immense forms like the ocean feel intimate. I began to see winged sharks, protozoa, creatures from Pleistocene seas, things that move like eels. Skip The Cut-Outs at the peril of your deepest viewing pleasures and expanded capacities for appreciating great art. Book your timed tickets today; they’re already selling out.

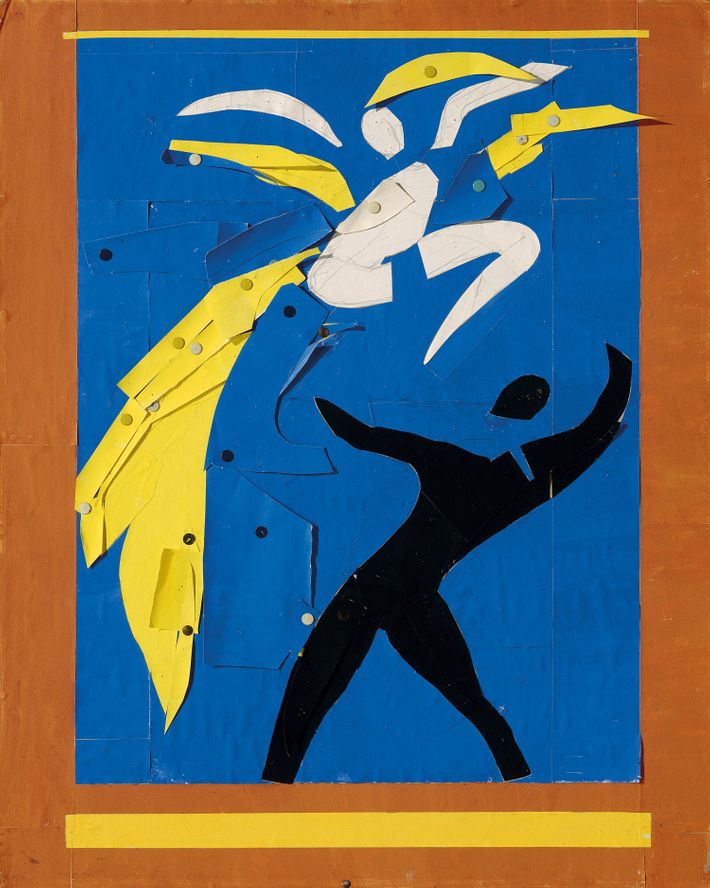

The first work in the first gallery, Two Dancers, rattled the walls of my perception. Two Dancers is a medium-size design for a stage curtain from 1937–8 — I hadn’t quite known Matisse was this far along in the process this early. Nearby images confirm that he was already experimenting with cutting and pasting paper as early as 1933. By 1937, he had already developed an intensely meticulous, canny practice — a process so simple, it’s shocking no one had gone all-out with it in this way before. Look closely at Dancers. See the gouache-covered paper cut and pasted and mounted on board. Notice the inconsistencies in the color coating, brushstrokes, and barer spots. Multiple pinholes and tacks evince how each piece of paper was shifted in space until it fell into compositional place. An aesthetic photosynthesis is revealed. Paper ripples, indents, bends; cuts overlap, are smooth, jagged. Everything is abstract, yet palpable. There’s no illusion at all; every move is revealed; no tracks are covered or smoothed over. In just one work, we’re immersed in a different notion of touch — cutting into paper as drawing, tacking as sculpture, surface and color as blocks of paint. Already present in Dancer are the phosphorescent colors, multiplying shapes, kaleidoscopic composition, incantational beauty, and camouflaged forms that will mutate into unforeseen objects that mark almost everything else here. Even though it’s titled Two Dancers, I see a fabulous firebird rupture in the upper ultramarine waters of the picture.

Few artists reward prolonged scrutiny more than Matisse, and in scrutinizing him, a beautiful paradox arises: The Cut-Outs are some of the easiest great works to love in the history of Western art. Yet they contain some of the most complex spatial architectonics in all of art. Without any kind of shading, rendering, or cross-hatching, Matisse is layering space without illusionism; the eye is always savoring surface and different internal juxtapositions. In addition to the physicality of the surface, Matisse gets different-colored paper to conjure tiny changes in spatial depth. Shades of color on similar shapes might be reversed to make one shape come forward and the other go back. He gets lighter colors and larger forms to go back into space and darker colors and smaller shapes to come forward. This should not work according to our laws of perspective and color theories. New visual ordinances form. Whole careers have sprung in some part from The Cut-Outs, notably those of Robert Motherwell, Ellsworth Kelly, and Richard Tuttle. The Egyptian levels of optical clarity, blocky shapes, and opaque color have helped form contemporary artists as varied as Gary Hume, Wangechi Mutu, Huma Bhabha, and Joe Bradley. And I surmise this show, too, will exert a pull on artists everywhere, now and in the future.

Yet despite all this visual firepower and radical experimentation, many persist in dismissing Matisse as a painter interested only in prettiness and making art “a comfortable armchair.” The unspoken charge is that “He’s not as powerful as Picasso.” Or macho. Just last month, an Artforum writer decried The Cut-Outs as “sensuous distraction.” This has been a party line since 1908, when Gertrude Stein recorded that “the feeling between the Picasso-ites and the Matisse-ites became bitter.” In 1925, “Picassoite” Jean Cocteau wrote that Matisse painting in the sun-drenched South of France had “turned into one of Bonnard’s kittens.” This prejudice goes beyond the need for heroes and powerful male figures; it comes from the fear of art being too beautiful, girly, gay-looking, ornamental, or decorative, and can be traced back to the proscriptions against pleasure, sensuality, and sex in Judeo-Christian tradition. Similar arguments were used against geniuses like Boucher and Fragonard and all of the Rococo, which was seen as too feminine and frilly to be taken seriously. Interestingly, these proscriptions never existed in Asia, Oceania, or Africa. It has never been explained why pure beauty, form, color, comfort, or even kittens are any less visceral than a picture of a bull with a naked lady being raped in the background. Part of what makes The Cut-Outs feel especially electric today is that few artists buy the old bogus arguments.

Plus, there is pain in them. Lots of pain. In fact, the kitty-cat Matisse said that before working, he wanted “to strangle someone,” and that making art was like “slitting an abscess with a penknife.” Nearly everything you’re seeing was made while Matisse was confined to bed or in a wheelchair. Unable to walk, he chose colors for assistants to paint on paper, directed them to place shapes, and pointed at or drew on surfaces with a long stick. He’d already suffered a colostomy and pulmonary embolism. Knowing the end was near, suffering all day, he was unable to sleep for more than a few hours, sometimes waking up in cries of physical agony that could be heard a quarter-mile down the road.

The Cut-Outs are Matisse’s long good-bye to painting — but not a bitter one. He never painted again after 1948, saying “Painting seems to be finished for me now.” He saw that the four sides and semi-rigid surface of painting was holding him back; the processes of painting itself could not create the tangible real surface he longed for. In paintings, he said, “I can only go back over the same ground,” while The Cut-Outs allowed him to “cross into a different dimension.” The Cut-Outs, he noted, were “beyond me, beyond any subject or motif, beyond the studio … a cosmic space.” Which brings us back to Picasso. After looking over their shoulders at one another’s work for decades, Matisse just went his own way. But Picasso knew a new “cosmic space” was in the offing. Accompanied by Francois Gilot, he visited the ailing Frenchman often. Gilot recorded seeing The Cut-Outs: “We were spellbound, in a state of suspended breathing.” After one visit, Matisse wrote of Picasso, “He saw what he wanted to see. He will put it all to good use in time.”

As for what we can see — our eyes can only stand so much, but gather your forces for the mind-bending extended crescendo to come. In the last four or five galleries are what I think of as the masterpieces in this show. The huge gaga dreamboats that alternatively have the majesty of Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, the marbleized flying power of Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel frescos, the shimmering lightness of being of the Blue Mosque, blues as blissful as those in Fra Angelico. Chinese fish mutate into heraldic underwater beings, a beautiful bathing nude is looked at from deep within a candy-colored canopy of palm fronds by a parakeet that must be the dying Matisse. A wraparound frieze of splashing bathers is part swimming pool, part Greek temple, and part Zen garden of delight. The enormous abstract Snail turns history painting into prehistory painting. Seeing all these visual facts beyond facts, we witness a mighty tree falling in art’s forest. And we beguiled are transformed into things that move forward like eels, mouths forever agape in this Sea of Love.

The Museum of Modern Art, 11 W. 53rd St.; through Feb. 8, 2015.