At 84, Sir Trevor Nunn is making his first attempt at Uncle Vanya, Anton Chekhov’s 1899 tragicomedy of turgid work and hopeless love on a failing rural Russian estate. Familiar with the largest stages – having run both the National Theatre and the RSC – Nunn is working in one of the smallest, Richmond’s Orange Tree, although it would be an injustice if this version ends there.

The minimalist space brings one immediate gain. Frequent references to the characters living suffocatingly together often seem fanciful in vast auditoria. Chekhov’s reputation can command, but here theatregoers nervously tuck their feet in as the eight actors drink, dance, duel and kiss within touching distance. So rawly authentic are the lines and looks that it feels as if we have somehow tuned into a late 19th-century Russian TV documentary.

A tangibly oppressive atmosphere, with lighting by Johanna Town and sound by Max Pappenheim, is defined by liquids craved (tea, vodka) and unwanted (tears, sweat, rain). Always alert to physical and historical detail, Nunn here makes hair, in an era and region short of salons, almost a subplot. Only a bald man – William Chubb as the desiccated academic Professor Serebryakov – looks neat, more hirsute fellows sporting wild spirals that appear self-hacked while they were half-cut. The women have long locks either flowing, braided, bunned, netted or scarved.

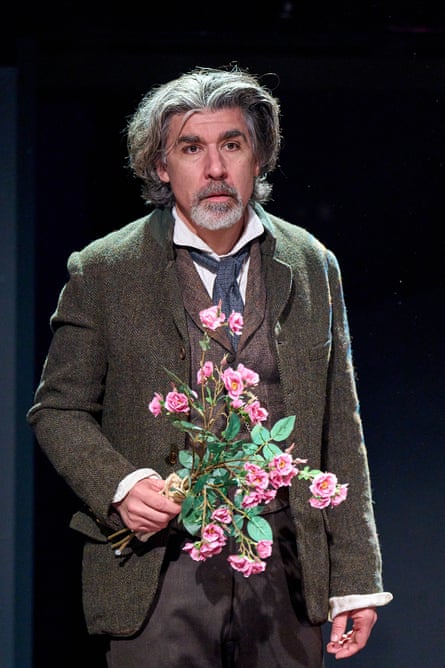

Other productions have been starrier in individual roles, but Nunn has drawn an immaculate ensemble. James Lance’s scathing, near-deranged Vanya still hints at the underlying spirit and intelligence that boredom and booze erode daily. Madeleine Gray makes Sonya’s naive and cheery demeanour a mask that heartbreakingly fractures. In this play, Chekhov most draws on his experience as a doctor, with plot twists involving gout, depression, alcoholism and morphine. Coutured and costumed to resemble the playwright, the Dr Astrov of Andrew Richardson, who made a dazzling professional stage debut as Sky Masterson in the Bridge’s Guys and Dolls, impresses as a physician destroying his body while inflaming women’s.

Trained at drama critic school to avoid open emotion, I was at first embarrassed – then vindicated by the reaction around – at my frequency of eye-wiping during the astonishing third act, in which Sonya, who secretly loves Astrov, unwisely commissions Lily Sacofsky’s equally besotted, married Elena to probe the doctor’s emotions. This is Chekhov at his most Shakespearean and Nunn combines his deep knowledge of both writers in a late career triumph.

At the Orange tree theatre, London, until 13 April. Available on demand, 16-19 April.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion