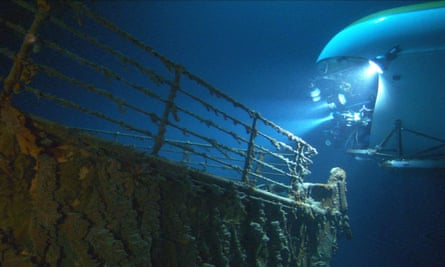

An immense railing, gnawed at by metal-eating bacteria for more than a century, emerged amid the pitch black waters. For more than two hours, the submersible had plunged through the water column to reach the depths of the Atlantic; now its lights bobbed over the prow of a ship dripping in red and orange icicle-like formations.

“My heart just started beating,” says Bill Price. “It was just like ‘Oh my God, this is amazing. This is the actual Titanic.’”

The 2021 expedition catapulted the 70-year-old retiree on to a shortlist – believed to number fewer than 300 people – who have visited the wreckage of the tragedy since the site was discovered 2.5 miles underwater, more than three decades ago.

The hours-long visit came at a steep cost, with Price, the former travel company president, digging into his life savings to fork out the $250,000 (£212,000) fee. “It was a worthwhile investment for me,” says Price.

More than a century after the luxury liner collided with an iceberg – its sinking in 1912 claimed the lives of at least 1,500 people and gave rise to a wave of books, films and songs – today, the scattered debris, 400 nautical miles off the coast of Canada, is at the centre of an ambitious push to foster deep-sea tourism.

Since 2021, the Bahamas-based OceanGate Expeditions has ferried about 60 paying customers and 15-20 researchers to the site in a deep-diving submersible, aiming to bring them within inches of one of the world’s best-known shipwrecks.

“We started the business and it was this idea of researchers and wealthy people,” says Stockton Rush, the company’s president. “Is there a way to match those people who wanted to have an adventure travel experience with researchers who need funding and a sub?”

Q&AWhat is the Shipwrecked series?

Show

There are 3m lost vessels under the waves, and with new technology finally enabling us to explore them, Guardian Seascape is dedicating a series to what is being found: the secret histories, hidden treasures and the lessons they teach. From glimpses into storied wrecks such as the Titanic and Ernest Shackleton’s doomed Endurance, to slave vessels such as the Clotilda or Spanish galleons lined with plundered South American gold that confront us with our troubled history, shipwrecks are time capsules, holding clues to who we are.

But they are also ocean actors in their own right, home to huge colonies of marine life. They are victims, too, of the same threats faced by the ocean: invasive species eating away at their hulls, acidification slowly causing them to disintegrate. Shipwrecks are mirrors showing us not just who we’ve been, but what our future holds on a fast-heating globe.

The pull of these wrecks has been a boon for science, shedding light on a part of the planet that has been shrouded in mystery. “If shipwrecks are the sirens that lure us into the depths, they encourage exploration into what truly is the last frontier of the planet,” says James Delgado of shipwreck company Search Inc. “A frontier that we don’t really know much about.”

Chris Michael and Laura Paddison, Seascape editors

The initiative hints at the outsized role that shipwrecks – whether ill-fated behemoths like the Titanic or Tudor warships – continue to play in our collective psyche. More than 3m vessels are believed to be scattered across the ocean floor, collectively offering a tale of triumphs and disasters that stretch back millennia.

Scores of these sunken vessels continue to shape our present. Some, such as the gold-laden Spanish galleon San José, found off the coast of Colombia, have forced a reckoning with colonialism, as several parties lay claim to a cargo that could be worth as much as $17bn. Others, like the near-perfectly preserved Endurance, found this year in the Antarctic, add a thrilling instalment to Sir Ernest Shackleton’s odyssey to save his crew after his ship was swallowed by the icy landscape.

The existence of these wrecks sits somewhere between life and death; their decaying structures often bearing witness to the tragic loss of human life, even as corals, fish and anemones flock to them, transforming them into sites teeming with marine animals.

This duality has been key to unlocking the story of these wrecks, says Jay Haigler, a board member and one of the lead instructors for Diving With a Purpose, a US-based volunteer group that focuses on locating and documenting shipwrecks connected to the global slave trade.

“One of the signatures of the slave ship is what we call a ballast pile, which are rocks or some kind of weighted material that offset the weight of human cargo,” says Haigler.

If a ship sinks, the nooks and crannies of these piles often end up becoming hotspots for marine life. “So if you see a coral mound, it could actually be a ballast pile, which could be connected to an actual ship that was involved in human trafficking and the global slave trade.”

His group aims to reclaim the painful legacy of these ships, to honour their ancestors by telling the stories of the people forced on to them. But the transformative power of these waterlogged wrecks hit home for Haigler in May, after he was among those invited to explore the Clotilda, the last known ship to have transported enslaved Africans to the US.

More than 160 years after the schooner was deliberately sunk in an Alabama river, Haigler slowly dived through its cargo hold, forced by zero visibility conditions to feel his way through an enclosure that once held 110 men, women and children.

It was a glimpse of what the journey may have been like for the captives onboard. “Because it was designed specifically for these captured Africans, it was completely dark,” he says. “Imagine 110 people in a space that is less than 500 sq ft, who travelled for over two and a half months in this cargo hold.”

Shortly after emerging from the wreck, Haigler met some of the descendants of the ship’s captives, offering his experience as tangible evidence of their long-silenced stories of resilience and identity, as well as the pervasiveness of the slave trade. “It was a very surreal experience,” he says. “I came out of that cargo hold a different person than when I went into it.”

The story of the Clotilda has been kept alive through the oral histories of the descendants of captives who were freed, though it was ignored by those in power because of the uncomfortable link to a wealthy, influential family. The tale has since given rise to documentaries, books and works of art.

It’s little wonder, says James Delgado, the senior vice-president of SEARCH, Inc, the company involved in the search for the wreck. “In many ways, the shipwreck has become a muse because it has a powerful story to tell,” he says. “Shipwrecks are a mirror that we can look into, that tell us more about ourselves as people.”

after newsletter promotion

The pull of these wrecks has been a boon for science, as the often deep-sea locations help shed light on a part of the planet that has been shrouded in mystery. “If shipwrecks are the sirens that lure us into the depths, they encourage exploration into what truly is the last frontier of the planet,” says Delgado. “A frontier that we don’t really know much about.”

In recent years, researchers have begun to understand how shipwrecks interact with the environment, scrambling to glean as much information as possible from sites before wrecks are reclaimed by the sea. Even in the case of big vessels such as the Titanic, researchers have documented the steady deterioration of the wreckage, with one expedition speculating that nothing would be left by 2030.

At times, researchers have found themselves on the losing end of this battle, watching in exasperation as history takes a backseat to the explosion of marine life at these sites.

“We would hope that the shipwreck is a bit of a time capsule that has lain undisturbed for thousands of years,” says Lisa Briggs, a research fellow in underwater archeology at Cranfield University in the UK. “But when you get a cheeky little octopus bringing important artefacts inside a piece of pottery or inside another artefact, it really starts to skew our impression of what was contained in those pots.”

Their race against time is exacerbated by the climate crisis. Stronger storms have left wrecks facing off against fiercer swells and currents, while the increasingly acidic nature of the ocean has prompted concerns that the erosion of their structures could be accelerated.

Briggs has watched as rising water temperatures have transformed the sites where she works. In Turkey, populations of invasive, venomous lionfish have flourished, making the work of cataloguing shipwrecks far more dangerous, while a worm-like marine mollusc that ravages wood has moved northwards into the Baltic Sea. “I’m terrified to think that some of these incredible shipwrecks might disappear due to these really annoying little worms that target wood underwater,” says Briggs.

As the climate crisis tightens its grip, exposed shipwrecks have become an unexpected symbol of an ailing planet; in 2016, melting ice in the Arctic led to the discovery of two whaling ships that had sunk in 1871, while Italy’s worst drought in 70 years revealed a 50-metre cargo barge sunk during the second world war.

In the case of the Titanic, the doomed liner has become a potent metaphor amid humanity’s steadfast refusal to heed more than six decades of climate warnings. “Part of the Titanic parable is of arrogance, of hubris, of the sense that we’re too big to fail,” James Cameron, the director of 1997’s Titanic movie, told National Geographic in 2012.

“We can see that iceberg ahead of us right now, but we can’t turn,” he added. “We can’t turn because of the momentum of the system, the political momentum, the business momentum. There are too many people making money out of the system, the way the system works … and those people frankly have their hands on the levers of power and aren’t ready to let them go.”

For the Titanic, this inertia resulted in a staggering loss of life; of the more than 2,200 on board, just 706 survived. The magnitude of the tragedy was not lost on Price, the retired former travel executive, as he eyed the wreckage strewn across the floor of the Atlantic.

“On the internet you read things like, ‘Don’t go there, it’s a graveyard, or you shouldn’t be visiting the area,’” says Price. “But we had moments of silence and things of that nature to be respectful of people who did lose their lives in that tragedy.”

It was a nod to the myriad roles the luxury liner plays in our collective consciousness – a repertoire that the company behind the expeditions is hoping to build on.

Ultimately, OceanGate Expeditions envisions a frontline role for the shipwreck – and all that it represents – in demystifying how one of the planet’s least-understood environments is changing. More than 80% of the ocean remains unexplored, even as humans expand their reach into it through activities such as deep-sea mining and overfishing.

“We spend 1,000 times as much exploring space as we do exploring the ocean in the US,” says Rush, the company’s president. “How the ocean responds to climate change is going to dictate everything. We need to understand it.”