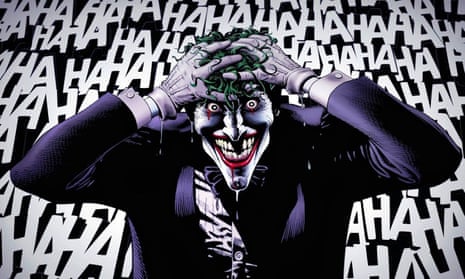

When The Killing Joke was published, 30 years ago today, it was instantly hailed by critics as the greatest Batman story ever told. Written by Alan Moore, the comic won an Eisner award in 1989, hit the New York Times bestseller list a decade after it first came out, and was adapted into a R-rated film. The ripples have been felt across superhero comics ever since.

It is an important comic book for many reasons, not all of them worth celebrating. The 46-page psychological slug-fest posits the ultimate standoff between Batman and his oldest foe, the Joker; the green-tressed villain wants to prove that all it takes to make a sane, ordered person slip into madness is “one bad day”. His bad day being when his wife and unborn child died in a tragic accident, the Joker suspects that Batman has had his own formative, shocker of a day at some point – which readers know is right, since he saw his parents gunned down in front of him as a child.

But it is not the Batman who the Joker wishes to drive mad – they’re both already there, in their own, very different ways. The subject of the experiment is Commissioner Jim Gordon, who the Joker kidnaps, strips naked and exposes to a nightmarish, de-humanising experience in an abandoned funfair.

It is here that the tipping point occurs; if not for Gordon, certainly for the reader. When kidnapping Gordon, the Joker and his thugs shoot his daughter Barbara, injuring her spine and paralysing her. The young woman, who is also Batgirl, is then stripped naked and subjected to a humiliating photoshoot, with the photos later blown up to monstrous proportions in an attempt to nudge her father over the edge.

The story goes that Moore asked DC if they were OK with how he treated Barbara Gordon; editor Len Wein reportedly responded, “Yeah, OK, cripple the bitch.” As Moore doesn’t speak about The Killing Joke (or any of his DC work) any more, and Wein died last year, it’s perhaps a piece of comics apocrypha we can analyse however we want.

What we do know is that Moore disowned the comic, and not just because of contractual sparring with his former publisher. A couple of years ago, answering a question about The Killing Joke in a Goodreads Q&A session, he said, “I thought it was far too violent and sexualised a treatment for a simplistic comic book character like Batman and a regrettable misstep on my part.”

Since the 1980s, comic studios have frequently released stories that sit outside their main storylines, self-contained works existing in their own bubble. But Barbara Gordon and her wheelchair persisted beyond The Killing Joke; she took on a new persona, Oracle, and fought crime from behind a computer. Barbara was an original member of the Birds of Prey superteam, eventually written by Gail Simone, who was also one of the founders of Women in Refrigerators. Named after an infamous act of violence in Green Lantern (involving a woman and a fridge), the campaign drew attention to the trope of female characters being injured, killed or abused merely to give men motivation for revenge – and Barbara Gordon’s ordeal at the hands of the Joker was one of the most famous.

In a way, a lot of good came out of The Killing Joke. In 2011, Simone began writing new Batgirl comics for DC, starring a physically rehabilitated Barbara who still endures post-traumatic stress disorder – an issue that might not have been aired otherwise. Barbara Gordon showed that it was possible to survive, and to fight back. And, with 30 years of hindsight, male writers should think twice about how they portray women in their books – and expect to be called out on it when they get it wrong.

Quick GuideThe five Alan Moore comics you must read

Show

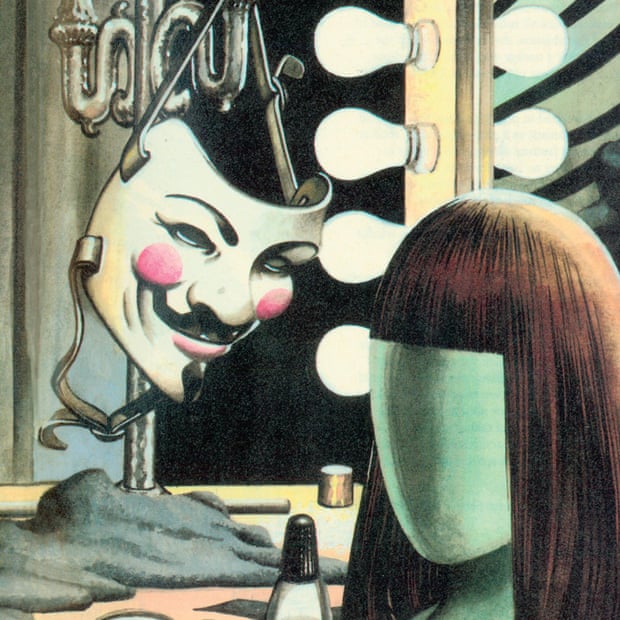

V for Vendetta (1982 - 1989)

This dystopian graphic novel continues to be relevant even 30 years after it ended. With its warnings against fascism, white supremacy and the horrors of a police state, V for Vendetta follows one woman and a revolutionary anarchist on a campaign to challenge and change the world.

Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow (1986)

Moore's quintessential Superman story. Though it has not aged as well as some of his work, this comic is still one of the best Man of Steel stories ever written, and one of the most memorable comics in DC's canon.

A Small Killing (1991)

This introspective, stream-of-consciousness comic follows a successful ad man who begins to have a midlife crisis after realising the moral failings of his life and work.

Tom Strong (1999 - 2006)

A love letter to the silver age of comics that nods to Buck Rogers and other classics of pulp fiction. Tom Strong embodies all of the ideals Moore holds for what a superhero should be.

The League of Extraordinary Gentleman (1999-2019)

One of Moore's best known comic series, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is the ultimate in crossover works, drawing on characters from all across the literary world who are on a mission to save it.

Leaving aside Barbara Gordon, The Killing Joke remains technically superb in terms of its writing and art. Alongside Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen, Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Sandman and Hellblazer, The Killing Joke was part of a 1980s movement that changed the attitude of comics being something just for kids. They became darker, richer, more sophisticated.

Three decades on, The Killing Joke’s legacy could be regarded as balancing between two polarised positions – not dissimilar to the Joker’s own “one bad day” hypothesis. Could a comic that Moore himself felt was too violent, too sexualised and “a regrettable misstep” push the medium over the edge into something reprehensible, where anything is permissible in the name of entertainment? Or would comics, just like Barbara Gordon, ultimately prove too resilient? I hope it is the latter.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion