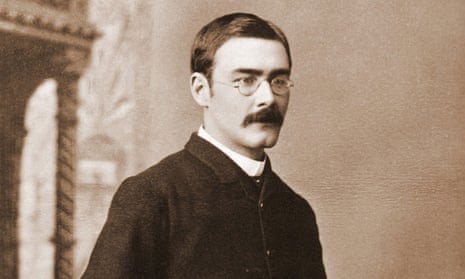

His stories have delighted generations of children and adults, while also being criticised for extolling the virtues of empire. Now, previously unknown tales by Rudyard Kipling are to be revealed in a major collection of his short fiction.

Eighty-six stories and fragments dating primarily from the 1880s, when Kipling was a young journalist in India, feature in The Cause of Humanity and Other Stories, to be published next month.

Some of the stories have never been published before and others appeared in publications “so rare that practically no one has had the opportunity to read them”, the book’s editor, Thomas Pinney, told the Observer. “They’re not all written to the same level but there’s a terrific variety.”

Most of the new material dates from Kipling’s seven years working for India-based newspapers the Civil and Military Gazette and the Pioneer. Kipling was born in the city then known as Bombay in 1865, and many of his most famous stories were inspired by life in India under British rule, including The Jungle Book and his final novel, Kim.

Unpublished stories in the collection include At the Pit’s Mouth, not to be confused with a tale with the same title published in 1888. Set in India in 1884, it’s the unfinished story of the love between a married woman and an unmarried man. “They’re planning to flee India and go to America,” said Pinney. “Before they do, he has a dream in which they both fall to their deaths, and their disembodied spirits observe what’s happening… It’s very complicated, very vivid.”

Pinney said. “It’s a 12-page manuscript. On the right-hand side is the story and on the left is a set of commentaries, some in Kipling’s own voice, some in the voice of the characters, some technical suggestions, some more reflections... It’s Kipling talking to himself as he works.”

The opening passage reads: “I, Duncan Parrenness, having fallen in love, on my way out to India last time, with Mrs George Festin, wife of a red-nosed, fat, bloated major of that ilk at Kassauli. Intimacy began in the usual light-hearted way on board ship, helped out with usual scenic accessories: moonlight, phosphorescent sea and long tête-a-têtes…”

Unpublished fragments in the book, from Cambridge University Press, include Sons of Belial, thought to have been inspired by a meeting with a “monstrosity” of an American boy. Set on a steamer, the story sees the boy tossing a major-general’s hat into the sea. Kipling wrote: “The elder Schwammaker, aged ten, ran yelping with laughter to the shelter of the galley. He had crept behind the major-general and twisted the old gentleman’s hat into the sea. Pursuit was impossible.”

Another story is The Cause of Humanity, running to almost 7,000 words, in its first publication since a privately printed edition of 100 copies. Pinney, emeritus professor of English at Pomona College, California, who edited the Cambridge edition of the Poems of Rudyard Kipling, calls it a “bizarre” story about transporting bodies from the Balkans to Britain for medical research because a shortage of “corpses to dissect” is “holding up the advance of science”.

Pinney writes in the introduction that Kipling was testing his skill by trying every possible literary form and mode – “narrative, anecdotal, farcical, tragic, historical, fantastic, confessional, parodic, dramatic”.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion