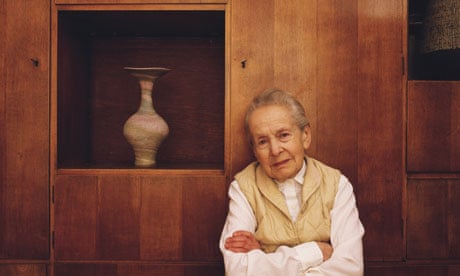

Even in old age the potter Lucie Rie, slight, immaculate in white, could be dauntingly rude. I wanted to write "direct", but this doesn't capture her ability to speak in a way stripped back from social niceties. Years later I realise that it was a habit, shared by other Viennese émigrés, of getting to the point. She answers a writer's request: "I do not want to be in your book. I like to make pots – but I do not like to talk about them. I would answer your questions today but they would be wrong tomorrow." She tells students at Camberwell College that their work is hopeless and to try teapots "for discipline". There was a divide between émigrés, those who never mentioned Vienna and those who couldn't stop, artists who explain their lives and those who are silent. She fell into the latter category with some force.

Reading the new wonderful biography of Rie (1902-95) by the late Emmanuel Cooper, I kept thinking of getting to the point as the subtext of the trajectory of her life. Born in an apartment off the Ringstrasse into affluent, assimilated Jewish culture, her life was one strong iteration after another of independent thinking. Through her training as a potter in Vienna to her exile in London, and to her creation of a style of making that had no counterpoint in the earthy functionalism of British pottery, she projected a force-field of separation from the expectations of those around her.

Vienna could be toxic for a young woman in the arts. There were comments by Adolf Loos about "Frauleins who regard handicrafts as something one can earn pin money or while away one's spare time until one can walk up the aisle". They were "daughters of senior civil servants". The Wiener Werkstätte was renamed the "Wiener Weiberkunstgewerbe", the Viennese Vixen Crafts Association. In Joseph Roth's The Emperor's Tomb, a novel set between the wars, the hero returns to discover news of his estranged wife. He guesses from the demeanour of his mother that his wife has become something dreadful, like a "dancer": "My mother shook her head gravely and said, almost mournfully, 'No a craftswomen. Do you know what that is? She designs, or rather carves, in fact – crazy necklaces and rings, modern things, you know, all corners, and clasps of fir.'"

Rie learnt to make pots in Vienna in the 1920s. She studied at the Arts and Design School with the great designer Josef Hoffmann, a man who had a strong sense of how handmade objects could work in settings of luxurious simplicity. Hoffmann's vision of all the arts and crafts working together depended on wealthy and informed patronage, something that Rie benefited from in her early career. Her austere pots – mainly dishes and bowls – were glazed to give a rugged and pitted surface, the perfect kinds of pot to sit on a sideboard in a light-filled Modernist apartment. You can imagine them, a trio of vessels perhaps, with an abstract painting behind them and some good Bauhaus furniture in the foreground.

These early pots, modern things, were made with an extremely limited palette of colours: beige, white, grey and black on a few variants of beaker or bowl. It is possible to read them as parallel to the use Hoffmann, her mentor, made of the square throughout his work as an architect and designer – as a syntactical device, a way of allowing disparate elements to sit alongside each other. It allowed Rie to make coherent groups of work in a way that the baroque, effusively garlanded effusions of her peers could not.

Cooper brings alive Rie's tribulations of trying to separate her life from that of her mother, who lived in the neighbouring street. These were almost comically played out. You marry: you are given a room in the apartment. You are given a family apartment nearby, but instructed to keep a family maid. The maid leaves. You begin your working life as a potter: your mother handles the orders, another maid picks up pots from the workshop. But Rie, a fiercely determined woman, was successful from the start, winning gold medals in exhibitions and biennales across Europe.

She commissioned an elegant apartment from a young Viennese architect, Ernst Plischke, in which to live in Vienna and – crucially – in which to show her work. The flat had walnut cupboards and versatile shelves that could be rearranged and dismantled. Most poignantly, Rie brought her apartment into exile with her in 1938, re-erecting the shelves and tables and cupboards in the mews house in Bayswater in which she was to spend the rest of her life. Her workshop with its potters wheels, electric kilns, buckets of glaze, and the endless plaster moulds for the ceramic buttons which she made to keep herself going during the war, were downstairs. It was in this high-ceilinged studio that she employed other émigré artists as assistants, including the young Hans Coper, who she took on in 1946. Upstairs was a bit of moderne Vienna: careful arrangements of her pots to show to collectors over coffee and cake.

Rie's London was full of architects, writers and artists, many of them from similar urbane, middle-European backgrounds. This meant that her pots belonged to a distinctly contemporary world where pots took their place alongside other arts and within a modern lifestyle. There was no sense of pottery being a lesser art. You can see this self-confidence, this lack of grandstanding, when you look at the pots that she and Coper jointly made in the 1950s.

Unlike the potter Bernard Leach, whose studio in St Ives produced a huge range of green and brown Standard Ware, pots to fill every possible domestic need from casserole, soup bowl, honey pot to egg-baker, the pots from Rie's Bayswater studio were carefully chosen for a modern life. Rie and Coper didn't try to make everything. Their coffeepots and cups, with their dense matt black and white glazes, reveal an undemonstrative and controlled tension. Each pot is careful. Pick up a teacup and look underneath. There is the fine white line of the unglazed porcelain, the glaze stopping in a perfectly controlled way. And then there is a radiating series of very fine lines scratched through one glaze to another below, framing the joint seals LR and HC. All this work for the base of a cup. You could buy these beautifully considered sets in Heals in London or Bonniers in New York. They were perfect for wedding presents for a design-conscious young couple. They were reassuringly expensive.

This sense of objects being part of a much larger world is what makes Rie and Coper stand out as urban potters, rather than potters alone. They both seemed to make their own accommodation with modernity. There was an affection for the city as a place to make, which sets them apart from the deep, English emotional investment in crafts in the country. They were both Jewish European exiles who made their homes in London, Coper from Germany and Rie from Vienna. By looking at their work, how they showed it and who they sold it to, we can pick up a feeling of a completely different sensibility from that of English ruralist craftsmen. We can begin to see the start of the urban maker, someone who was at home in a contemporary world and not in flight from it.

Lucie Rie's pots reveal an instinct for powerful concision, for the paring back of forms, textures, functions to the essential. Her life reveals someone who was able to get to the point

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion