Antony Gormley has hurt his knee, which is a pain in more ways than one. He’s due in Italy in a few days’ time, to install the second of two new shows, and time is too short to be hopping around on crutches. His office is up a flight of external stairs, which are made of metal and get slippery in the rain, so he won’t be coming down again today. Though his assistant apologises that the huge warehouse studio complex downstairs is empty, it doesn’t appear so. Large metal figures, wrapped in plastic, hang from the beams like giant, conceptual bats. In a side room, specialist packers are constructing crates round other pieces, which are about to be shipped off here, there and everywhere. Outside, a couple of cast-iron figures stand in the drizzle, gathering the rust that will be part of their personality when they are sent out into the world. Isn’t there a risk they’ll get stolen? Gormley laughs, and points out that thieves would have to come with some serious heavy-lifting equipment.

The two shows, in Venice and in the Tuscan hill town of San Gimignano, will display the little and large of one of the UK’s most industrious sculptors, a knight of the realm, who is beloved for such towering public works as the Angel of the North at Gateshead and Another Place, the 100 figures that have stood on Crosby beach in Merseyside since 2005. But those who feel they know him, because they have been seeing works based on casts of his own lean body for so many decades, may find themselves perplexed by a new body of work that is altogether more theoretical.

“This is sort of Rodin’s Thinker on the toilet,” he says, of a cubist construction that will be presented in miniature in Venice and in giant form in San Gimignano. It’s called Stem, he says, as we peer at it on his computer. “You can think of Stem as stemming the flow. Or you can also think of it as a thing that gives support.” Titles are important to him, he adds. He likes singular words that are both definitive nouns and transitive verbs. “I don’t want my titles to be a closing; I want them to create an opening.”

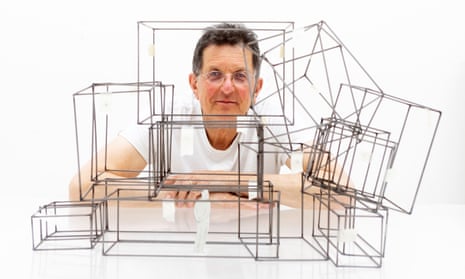

As he speaks, he struggles to his feet and hops over to his work table, where a model of another piece has pride of place. It’s called Frame, and is a maze of wires, with a small cutout of a human placed inside to give a sense of its scale, which will be huge. It will occupy the auditorium of an old theatre in San Gimignano. “I want people to look down on it from the boxes as people walk through it, bowing their heads to get in: here the auditorium becomes the place of a performance where art and life interact.”

I’m unable to make head nor tail of it until, in one of those extraordinary moments of prestidigitation that sometimes happen in conversations with artists, he explains it into perfect focus. “It’s based on the third position in a Muslim sequence of prayer, where the body is occupying the least possible space: you’re on your knees, your feet flat to the floor, but you haven’t yet touched your forehead to the floor.” Ah yes, suddenly I can see a person at prayer, the human in the apparently abstract.

When I tell him I feel anxious about looking at art in miniature and on screen, without seeing the work itself, he reassures me that it’s in keeping with his latest thinking, which is all about the relationship between the human body and architecture and the cyberspace in which we spend so much of our time. “I’m shocked myself when I look at my phone and it tells me my online time has gone from three to seven hours in the last 24. How is that possible?” he frets. “We treat our bodies almost like a dog that we have to take out and exercise and keep under very careful dietary control, rather than living a life of doing and making and engaging. I know that all sounds a bit luddite, but I think it’s just terribly important.”

This thought brings him back to Frame. “You have to say: ‘What the hell is this?’ Well, this is me saying: ‘Can we treat the space of the body as a sequence of rooms, as a concatenation of cells?’ But rather than making them solid, I’m going to use the language of space. So it’s a house-sized body. It’s the first time I’m no longer using the dead weight of blocks as the principle of them coming together, but linking them like a chain. And they can all be loose. The head, the arms, the forearms, the back of the legs and the feet are all completely independent, even though they are all connected to each other.”

It’s the culmination of half a century of thinking for the 71-year-old artist, who was the youngest of seven children born into the wealthy Catholic family of a pharmaceuticals magnate. He was educated by monks at a Benedictine boarding school, and has said that his parents chose his initials – “AMDG” – to offer their infant son up ad maiorem Dei gloriam (to the greater glory of God). Islam, he says, is so refreshingly uncluttered after the paraphernalia of icons and images that choked up the churches of his childhood.

His concern with the mysteries of space and form is evident in early work from his time as a postgraduate at the Slade in the late 1970s. He’s particularly proud of a nest of black bowls (pictured below), an attempt to capture infinity in a droplet of water, which could also be seen as an offertory – or prayer – bowl, a product of his lifelong interest in religion. Before art school, after graduating from Cambridge with a degree in archaeology, anthropology and the history of art, he took himself off to India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to immerse himself in Buddhism. It has remained a touchstone in his life, though, he says, “Having escaped from Catholicism, I’m reluctant to sign up to anything else.”

At the Slade he met Vicken Parsons, now his wife, who is up in the studio, eating lunch with him, but slips quietly out when I arrive. She became his assistant, then his collaborator, and is an artist in her own right. She was responsible for making his body casts, as well as raising their three children. In one early work, involving 600 loaves of bread – Mother’s Pride “because it was a food furthest from the field, part of a distribution network more akin to gas or electricity … it had nothing to do with mothers and very little to do with pride” – Parsons drew outlines of his body on two piles totalling more than 8,000 slices, which he hollowed out by eating the bread. The piece, titled Bed, was shown at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 1981, the year after the couple got married. “Bed was great for our relationship,” wrote Parsons, “it was exciting building this mad thing together.”

The first 20 years of his career were concerned with making lead-covered moulds of his body that, he says, “materialised the inner darkness. Not everyone will see it this way, but this is the truth. And you could say that the ability of them to be interpreted as rather bad statues was the risk I took. And the fact is that they are bad statues if you want them to be statues.”

Times change, and he has been criticised for, as one reviewer put it, “leaving representations of this privileged white guy around a world dominated by privileged white guys”. He bats away the charge, insisting that they have nothing to do with idealisation, or the sexualisation of the body. “Nothing to do with portraits, or all of the things to which the statute has to answer. For me they are reflexive instruments: they are saying: ‘Here is something that has captured the lived moment of human time, taking it out of human time and putting it in geological time.’”

He loves the damage that weather inflicts – hence the figures standing outside his studio – but he’s also mindful of his legacy, an interest that fortuitously coincides with environmental concerns about waste. Last year, he mounted a heroic rescue effort to restore the Crosby beach figures, some of which had fallen over and were being swept out to sea. “They were put there temporarily. And I think, had they been a permanent installation originally, we would have done it differently. When the people of Merseyside decided they wanted them to stay, I had a responsibility to make sure that they would last longer and we’ve done it now in such a way as they are guaranteed for the next 50 years. And, yes, they are purposefully oxidising, and the forms that are at the mid-point between high and low tide are spectacularly spalling, but the accidents of appearance are not of my concern.”

A more human-made threat faced the Angel of the North, when planners decided on a road-widening project that it was feared might obscure the view of what has arguably become the country’s best-loved modern landmark. An application for listed status was turned down on the grounds that it was less than 30 years old. In fact, says Gormley, it has so far worked out rather well for the Angel, removing some of the trees planted at the time of its installation in 1998, which had grown up to obscure the view. “I said to them at the time: ‘The whole point of the Angel is that it sits on a mound that it shares with visitors, which was made from the destroyed pithead buildings of the Lower Tyne colliery.’ The mound says: ‘You know, the Thatcher years annihilated all the collective memory of a 200-year dialogue between coal, iron and engineering.’ I wanted it to be a tribute to that history of pretty hellish working underground.”

He is still a regular visitor to Gateshead, where his works are cast. When the foundry he used got into trouble a few years ago, instead of finding another, he bought it up. “We’re nostalgic about the extraordinary sense of community that arises between people when they’re oppressed,” he says. “I don’t know what that says about human nature, but I do know that when I go up to Northumberland, I find people with positive attitudes and the ability to care for each other in a way that just isn’t common.” The affection is mutual. After a year of lockdown, nearly 7,000 people booked timed tickets to Sunderland’s Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art’s reopening show last summer to see Field for the British Isles, an installation of 40,000 tiny clay figures – affectionately known as Gorms – which won him the Turner prize in 1994.

But Gormley’s ambitions are far from parochial. Within a year of Field’s first UK outing, he was also exhibiting it in the former Yugoslavian states of Slovenia and Croatia, though an attempt to install it in a burnt-out Holiday Inn in the besieged Bosnian city of Sarajevo was turned down by the Foreign Office. “They said it was immoral to take art when what was needed was food. That’s a very limited view of what is necessary for the spirit,” he said at the time.

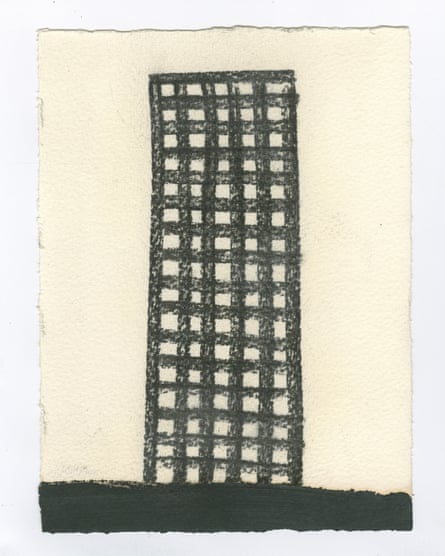

The rampant nationalism that those early Field trips aimed to counteract, by migrating art across borders and gesturing at a shared world, is sadly on the march again, its destructiveness evident in the silhouettes of ruined tower blocks in Ukraine. “These are now the images we’re receiving from Mariupol,” he says, “our high-density city-dwelling structure revealed to us as a skeleton.” Nor is this hellish scenario the sole preserve of countries at war. The spectacle of Grenfell Tower after the 2017 fire posed similar questions about a way of living that increasingly preoccupies him. Its bleakness is captured in a simple charcoal drawing: “Is this a beehive? Somewhere where our species can live in harmony, and a way of making honey,” he asks.“Or is it a prison that actually becomes the condition of alienation and despair?”

Though drawings and sketchbooks are part of what he now exhibits, he remains primarily a sculptor, on a mission to interrogate the whole purpose of sculpture. “People are still obsessed with images and finding things they can recognise,” he says. “And what am I doing? Well, I’m inviting people to explore the conditions of their own living. It’s a big risk, and it may or may not work. But I guess everything in my exhibitions is a test site for asking three questions: what can sculpture do? Can we make it in a different way? And what is an exhibition anyway?” The title of the San Gimignano show is Body Space Time. “Three short words which I think say it all.”

The shape of things: Antony Gormley on choice cuts from his 50-year career

Small Stem Model (2019)

“This is Rodin’s Thinker on the toilet, with its head dropped on to its folded arms. It was a huge evolution for me. I’ve never made something so absolute. In the Venice show it’s a small graphite model; in San Gimignano it’s lifesize, and it had to be accurate to 200ths of a millimetre. This is me trying to materialise the internal space of the body in the language of architecture. This is where I am now in the work – but that idea of mapping the inner space of the body has been in the work for a long time.”

Grenfell II (2017)

“I felt that what happened to Grenfell Tower was such a tragic story of human greed and laziness and wishful thinking. But it was also about the absolute opposite: an extraordinary community, with its artists, social workers, nurses and teachers. When you saw it from the Westway after the fire it was a black outline, not dissimilar from my charcoal drawing, asking the same questions my sculptures ask: is this the condition in which we live? Is this now our habitat?”

Full Bowl (1977-78)

“This is a hand-sized bowl I made at art school, which still makes me think. It’s filled with smaller bowls and seems to ripple out, like water. It’s a conceptual work, but the thing that excites me is that in the middle is a void: an empty bowl, surrounded, as it were, by space at large. It’s exploring the unreliability of edges. In other words, where something begins and ends is maybe delusionary.”

Subject III (2021)

“Now that over 50% of our species lives within the urban grid, we are implicit in and dependent upon our context. So this is a body in a position of supplication, though it isn’t actually praying. I think it is saying that we are now supplicants within an organisation of the world that is in our computers, our digital technology, as well as in the axial grid of our cities, and the horizontal and vertical planes of our architecture.”

Frame II (2022)

This model consists of a maze of wires, with a small cutout of a human placed inside to give a sense of its scale. The full-size version will occupy the auditorium of an old theatre in San Gimignano. “I want people to look down on it from the boxes as people walk through it, bowing their heads to get in,” says Gormley. “Here the auditorium becomes the place of a performance where art and life interact.”

Body Space Time is at Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, until 5 September. Lucio Fontana/Antony Gormley is at Negozio Olivetti, Venice, until 27 November.