Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, the seminal 1966 book by Robert Venturi, who has died aged 93, has always stuck out of my bookshelf. Like its author, it is an awkward thing, refusing to bow to the conventions of what shape a book should be. A recently published facsimile edition of Learning from Las Vegas, the radical manifesto he wrote with his wife, Denise Scott Brown, and colleague, Steven Izenour, in 1972, does the same thing today. It pokes out of the teetering piles of books gathered around my desk, a monumental tome that is impossible to ignore. Like the Vegas billboards it celebrates, it screams for attention.

Disrupting more than just bookshelves across the world, Venturi was one of the most influential figures in 20th-century architecture, taking an erudite sledgehammer to the dogmas of modernism and arguing for a world that embraced history, diversity and humour. His was a catholic big tent that rejected the “either/or” attitude of purity and order, arguing for the plural richness of “both/and”. It was a pop sensibility that placed as much value in the burger stand as the cathedral, an inclusive folk art approach to architecture that found joy in the everyday. “Less is more,” was the po-faced maxim of modernist maestro Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, to which Venturi gleefully retorted: “Less is a bore.”

I met Venturi and Scott Brown for the first time at 18, when I was working as an intern at the National Building Museum in Washington DC. They came to lecture on the occasion of being awarded the Vincent Scully prize in 2002, and performed a quick-fire slideshow of things that they loved, under the banner A Disorderly Ode to Architecture That Engages. It was a fun-filled ride, from Michelangelos and bungalows to ketchup bottles and cartoons, but presented with poker-faced gravity by this besuited pair of pensioners. They took their fun seriously. As Scott Brown would later write: “Be deadpan, don’t upstage your subject and (in the way Bob wears Brooks Brothers suits) present outrageous content in a conventional format.”

I eagerly queued to have my book signed (even Venturi’s signature was larger than life, incorporating the facade of the house he designed for his mother in a lively scribble), and on learning that I was from Yorkshire, his eyes lit up. “Vanbrugh! Castle Howard! It’s one of our favourite buildings!” I had been expecting him to wax lyrical about pop culture, but instead he began enthusing on the wonders of the English baroque. In an instant he transformed what had always been a tedious stately home in my mind, from a childhood of being unwillingly dragged around such places, into a magical-world of architectural games and theatrical tricks, a great house conceived as a series of stage sets. I hadn’t realised these old stone hulks were so full of mischief and wit.

Unexpectedly, the influence of Venturi would persist. A year later, the first essay I was set when I arrived at university was on his mother’s house, which he built in Philadelphia in 1964. It was the first time I learned how to read a plan and section, what to look for in a facade, how architecture could be representational: that meanings could be translated into physical space.

“It is both complex and simple, open and closed, big and little,” wrote Venturi. “Some of its elements are good on one level and bad on another.” I remember staring at the plan for hours, trying to work out why the staircase kinks awkwardly around the back of a chimney breast, as if each element was competing to occupy the centre of the room. In typically perverse fashion, Venturi wrote that the staircase considered on its own, tucked into a residual space, is bad. But, considered as part of the complex and contradictory whole, it is good. It performs a curious dance with the chimney, and splays at the bottom to provide a place to sit. The facade, meanwhile, acts like a Vegas sign, a thin screen that shouts “house”, through which the building’s inner complexities occasionally protrude, setting the symmetrical form off-balance.

It had a flatness, like layered stage scenery, that would continue to be a theme throughout Venturi and Scott Brown’s work. “Baroque architecture needed a depth of one yard to do its decoration,” they wrote. “Renaissance architecture perhaps a foot, rococo one centimetre, and art deco could suggest seven or eight overlaid surfaces in one bas-relief, one centimetre deep. We loved the richness within the deco low-relief, but when we came to think about what this meant for us today, we realised that our decorative surfaces should be two-dimensional – for many reasons, including cost.”

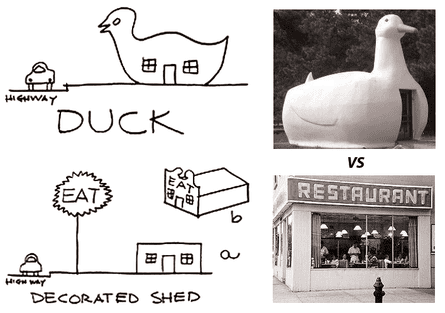

It was a kind of architecture they classified as the “decorated shed”, a functional box with ornament applied independently of what’s going on inside, which they set in opposition to the “duck”, where the architecture itself is a sculptural, symbolic object – named in honour of a duck-shaped egg-stand on Long Island. It is a useful classification that remains relevant, with the contorted ducks garnering media attention, while the decorated sheds sprawl across the landscape. They told me that wherever they went, they always played the game of “I bet I can like something worse than you can like”. It was an urge that Scott Brown described as “hate-love exhilaration,” an attraction to the weird, ugly or banal, that forced them to reflect on that attraction, and unpick the signs and symbols behind the world around them.

Venturi is often referred to as the father of postmodernism, but he was so much more than that. As the historian Robert Miller wrote, it is “a charge comparable to calling Thomas Edison the father of disco”. Like Edison, Venturi shone a bright light into the often gloomy world of architectural discourse, illuminating a colourful spectrum of possibility, embracing the messy vitality of the “ugly ordinary”, and expanding the very idea of what architecture could be.