Last winter, the Paul Klee Centre in Berne had a brilliant idea for an exhibition. They partnered a large selection of works by Klee with a broad sampling of the work of Klee's contemporary, Johannes Itten. When I saw it at the Martin-Gropius-Bau museum in Berlin, it was quietly devastating. Itten is one of those figures always referred to as "very interesting" by art historians, meaning almost the opposite. He was a contemporary of Klee's, and, briefly, a colleague when they both taught at the Bauhaus in its Weimar years from 1919. Itten was a curious person: he led a mystical religious movement at the Bauhaus called Mazdaznan, whose followers wore purple robes and ate nothing but garlic (Alma Mahler said that you could tell when you had walked past a Bauhaus student in those early years). Both Klee and he were somewhat mystically inclined, and thought deeply about the significance of colour. Both were restless creators, and their work changes dramatically every two or three years. They ought to be very good companions in a gallery survey.

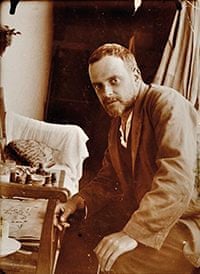

Instead, you felt intensely sorry for Itten. Every shift in style in Itten's work was expertly achieved, closely argued-for and deathly dull. His grid-pattern abstracts are so tedious they give the impression of boring even their creator. Strikingly, every time Itten moves from one pictorial manner to another, he seems to leave everything behind. There is nothing that would convince you that one of his 1960s abstracts, such as Adieu (1965) was painted by the same artist that reduced a leaning woman to a pattern of lines in Woman with Birds (1945) or a still life of vases in 1922. There is no character there at the core. But Klee has an irreducible centre, and though he changed his style and approach many times in the 40 years of his mature career, there is always something there that makes you say "Klee" without hesitation. When Klee appears in a photograph, I've observed that even people who don't recognise him are drawn to his extraordinary, warm, humorous face – there is an unforgettable one of him with his Great War regiment, his expression turning the spiked Pickelhaube he wears into a moment of pure comedy. His work is much the same. At the calm centre of his enormous fantasy, there is an ego-denying self, looking outwards into the world.

It is a colossal body of work, catalogued in the first instance by Klee himself. The Tate's survey focuses on the key exhibitions that marked the development of Klee's career, and shows the public face of the development of his art. His relationship with his public is a gripping subject, and includes such unwilling representations as the Nazis' Degenerate Art exhibitions. To penetrate into the deeper, private movements of Klee's thought and imagery, some consultation of his own catalogue, and the recent, still more extensive, catalogue raisonné, is indispensable. From 1911, he began to inventory every item of his work, going back to drawings he had made when he was three or four years old. From then until his death in 1940, he catalogued almost everything he produced, numbering it and ascribing it to a year. The huge and magnificent catalogue raisonné produced in Berne by the Paul Klee Foundation consists of nine volumes, accounting for 9,800 drawings, prints, paintings and illustrations: the backbone of it is Klee's orderly cataloguing habit. I have them, and they are thrilling volumes to read through, watching Klee burst out into something entirely new, developing from painting to painting. You can follow every step.

Take a moment in 1922. Klee was a first-rate musician, and music quite often surfaces in his art. Roughly in the middle of his year's production – number 142 of 260 numbered works – he goes back to music. We can see the order in which he created things, the direction that his mind went in, by following the works he created over a few days, in numbered succession. First, there is a colour-gradation exercise between a capital A and an O, called Overture – Klee had been teaching at the Bauhaus for about 18 months, and it seems to start from one of his colour exercises. Then a tiny piece of grotesquery, a drawing called Brewing Witches; a grotesque piece of musical comedy called The Heroic Tenor as a Concert Singer, and then three watercolours that seem to be part of a different pattern of thought, closely resembling each other. The mechanised tenor and his piano, a tiny mechanical box, set something off now, and we have an Old Steamboat, an oil-transfer drawing of impressively clanking appearance. Klee apparently wanders off into something quite different; two enchanting, weightless horticultural watercolours, Plants in the Moonlight and Project for a Garden. The work of these few days seems quite exploratory, quite undirected. But then the three strands of investigation unite in the magnificent Twittering Machine. The garden; the clanking machinery; the vision of music all come together in this vision of four birds at dawn, poised on a branch as their crank is turned and they burst into song.

To pluck moments from Klee's work at random is to be astonished by his variety of subject and approach. The fantastical oil-transfer drawings of the early Bauhaus years are what his name calls up – it was a process he invented, and the messy, joyously splodgy line is, indelibly, his own. But then Klee himself thought the translucent, miniature watercolours of Tunisia from 1914 were at the heart of his work. In his journal, whether written at the time or with subsequent reflection, he wrote of this moment "Colour and I are one. I am a painter." Or there are the grand, massive games of the very last years, where strong, thick lines are refused permission to cross or touch, as in Insula Dulcamara of 1938, or moments when the spray-paint techniques of the early 1920s shift into the centre of investigation.

There is a sudden interest in divisionist techniques in the Düsseldorf period of the early 1930s. Where does it come from? From Seurat, or from a memory of North African architecture? A key work is Portal to a Mosque in a Berlin collection, a graph-paper fantasy summoning up memories of Mamluk glasswork. The units grow smaller; the works ripple out into visions of landscape, like the 1932 Lowlands in a now-unknown location. For a couple of years, the divisionist fantasy is what a Klee looks like. Then it abruptly stops; he starts making geometrical figures out of unbroken lines and paintings and drawings out of short, feathery brush and pencil strokes. To be honest, I don't much like the feathery period, and Klee was glad to be out of it – it was his most fraught and least productive period, coinciding with the triumph of the Nazis. It doesn't matter. The beautiful divisionist period and the unsatisfying feathery period are over just as quickly as each other, and Klee hardly ever returns to either.

I have come to think of Klee as an exemplary artistic figure, facing outwards into the world and not painfully contemplative of the self, drawing mastery not just from his command of the medium, but from the struggles to control his tools. He doesn't necessarily intend to make a big statement; he often simply observes something in front of him, tenderly and exactly. (I never see a dog sleeping on a cushion without thinking of Klee.) In his career, he explores the possibilities of a particular mode or style, does what he can with it and then moves on to something quite different. Klee, you feel, could have carried on for ever. At the core of his work, however, there is something solid and irreducible that never changes, however alluringly different the surface of his work. He reminds one in a way of Stravinsky, who moved from Russian nationalist to cubist to neoclassicist to serialist without ever writing a bar of music that could be mistaken for anyone else's.

Was he, in Isaiah Berlin's famous definition, a fox or a hedgehog? Did the man who created the minimalist landscape Park near Lu in 1938 and the extravagant, grotesque and masterly Aged Phoenix in 1905 possess multiple personalities? Or can we look at the vivid satire of the early engravings and that of the 1930 Conqueror and say that here is someone whose values, at bottom, never changed? What is that central, unmistakable core that Klee possessed and that Itten went without?

The core of Klee, I think, is his comedy. One of the underestimated sources of modern art is commercial, comic art, and the exchange between the newspaper "funnies" and the most advanced art was easier than one might suppose. Artists of the time sought inspiration outside the long tradition of academic training: some in indigenous African or South American art; some (like Klee) in the art of children; others in commercial, advertising and even comic art. The line that goes from Toulouse-Lautrec to Beardsley to the Fauvistes is quite clear. Another line comes from the tradition of expressive distortion in caricature and satire into more expressionist styles – the physical distortions in Egon Schiele's portraits have precedents in Daumier's cartoons.

An extreme example here is the German-American artist Lyonel Feininger. After years of considerable commercial success as a comic artist for the Chicago Sunday Tribune, Feininger took the battery of distortion and simplification he had developed as the creator of Wee Willie Winkie's World into life as an expressionist painter and teacher at the Bauhaus. Klee never had a career as a comic artist in the rich satiric traditions of southern Germany and Switzerland. However, his early exercises in comic distortion and satire never went away. The early Munich images of disgruntled fish eyeing up a hook and line resurface years later, in a 1925 Fish Image, or in Fish Gaze from 1940 – unmistakably very stupid fish, those two – and in other treasured images of animals in their own society, such as a marvellously funny and tender Kingdom of Birds (1918).

Underlying all of this is a dream sensibility of distortion and misogynist grotesquery. The physical presence of humans, especially in the early images, is often shockingly obscene. The disturbing 1906 Puppet on Violet Ribbons has prehensile feet with long fingers, and a closely delineated anus where her vagina would conventionally be. In other works of this period, animals sniff at the pudenda of women; it is not always clear whether it is the animal's mouth or the woman's genitalia that is dripping fluid. Klee was determined to explore his fantasies and deep-rooted beliefs, however bizarre. In the so-called Diaries – not daily records, but examinations of recalled experience – he sets down a startling series of vignettes from early childhood. The traditions of the grotesque image, the dream-fantasy, the rapturous contemplation of the possible and the satiric humour are wedded from Klee's earliest days. "In a dream I saw the maid's sexual organs," he writes. "They consisted of four male (infantile) parts and looked something like a cow's udder (two to three years)."

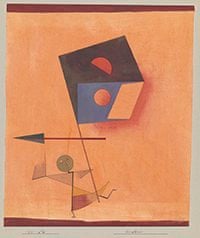

The satirical grotesquery and his willingness to distort material places Klee in a comic tradition. The well-known engraving Two Men Meet, Each Believing the Other to be of Higher Rank depicts two emperors, Franz Joseph of Austria-Hungary and Wilhelm II of Germany, naked, bowing low. A small anthology could be put together of Klee's satirical jibes at power, emperors, soldiers and dictators. They include such self-explanatory pieces as Pride of the Gatekeeper from 1929 and the evil-looking Sea Snail King from 1933. Satire stretches into beautiful design in the 1930 Conqueror. A small, geometrical figure, alone and running, bears a flag clearly too heavy for him to support. He seems to be running in one direction; a spear or a giant arrow, perhaps, is pointing in quite the other direction. He is going to fall over. Or, still more abstract, later in the 1930s, when the terror of the dictators had become completely clear, he painted the great 1939 Destroyed Labyrinth. Klee had long been drawn to fragments, half-signifying a lost civilisation; there are many images associated with Egyptian themes from earlier in his career. In Destroyed Labyrinth we see the remains of a tyrant; the walls were built to herd and harry and control people. Now they are in fragments; the builder's purpose is lost; across these small fragments, a child could find his way. Like all of Klee's later work, it is, on some level, a beautiful and noble statement against the tyrannies of his time. Like all of Klee's work, it does not itself dictate or control; it allows the eye to find its own way through its patterns and structures.

He is the artist I love best in the world: I love his modesty and his resourcefulness, and his willingness to combat oppression and violence with laughter. His work reflects the idea of Milan Kundera, that the machinery of power works by imposing forgetfulness; that the way the individual can fight back is through laughter. At the time, nothing could have seemed more fragile and pointless a gesture against the armies of Hitler than a painting of fish, gawping at each other, by a Dessau art professor. But nothing remains of Hitler's power, and the structures he built are mostly dust. What certainly does remain are is a little, tender picture of a garden; a sheet of luminous colours; music transformed into an image.

Klee died in great pain in 1940, waiting for the Swiss state to acknowledge that he was a citizen of the country in which he was born. It must have seemed to him that he had died in failure, in a world that he could do nothing about. As the exhibition of his incomparable, funny, inexhaustible work opens at Tate Modern, we can say that here is an artist who got more right than most.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion