Neil Young’s Boring, Prophetic Message to Readers

The musician wrote his new book, To Feel the Music, the same way he makes records—according to a highly evolved aesthetic of half-assedness.

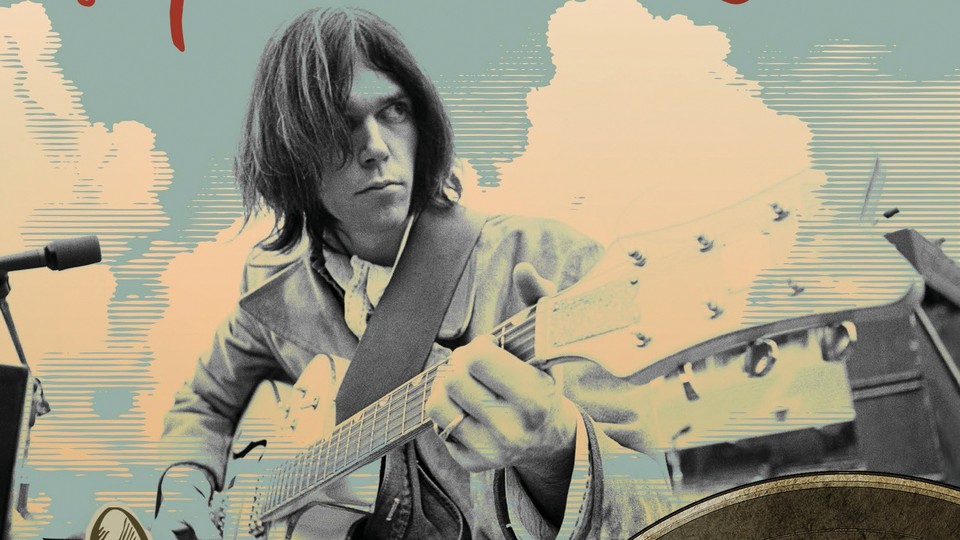

Let’s get the throat-clearing out of the way. Neil Young is a musical colossus, a modern father of the American imagination, and—at 73—still an unbelievable guitar player. Electricity pours through him, coming out of his instrument in sheared-off melodies and gerontic thrusts of noise. His great songs are life-altering. There’s no coming back, for example, from a full exposure to “Don’t Let It Bring You Down.” A sector of my nervous system is owned, forever, by Neil Young.

But he writes weird books, and this is another one. Deliriously boring in parts. Hard to market too, I would imagine, because where do you put it? Not with the rock-star memoirs—To Feel the Music is quite devoid of revelations and rockin’ anecdotes. Also, it has two authors, one of whom is not Neil Young. It’s sort of a business book, or a tech book. And yet it doesn’t really fit into those sections either—too woolly, too gonzo. An entirely new genre perhaps: the rock-star business-tech memoir by two authors.

To Feel the Music is the story of Pono, which was Young’s quixotic attempt to create and sell a new kind of portable music player and download service. Something that didn’t crush recorded sound into nasty little MP3s. If you’ve read either of his previous books, Waging Heavy Peace and Special Deluxe, you’ll be familiar with his preoccupation—his obsession, his foreboding—in this area. Young has long contended that with digitization, the conversion of music into data, has come a terrible shriveling of our sonic universe. You’ll also be familiar with his distinctively dazed, American Primitive prose style: “You have to give your body a chance to absorb [music] and recognize how good it feels to hear it. The human body is incredible. It’s great! It’s made by God/nature, depending on your beliefs.”

MP3s, and I’ll try to be as scientific as I can here, are evil. They go against God/nature by chopping music into numbers. I’m with Young 100 percent on this. Beautiful flowing music, sliced to bits! And what is the devil’s price for having the entire Tangerine Dream back catalog at your fingertips? Why, shitty sound quality. The sound coming out of my Bluetooth speaker is no longer a dimension; it’s a narrow pulse, a serrated wave. Bass-blurts, ragged spikes of treble, a terrible crowdedness or crammedness in the mid-range. My old-fart ears are squeaking in discomfort. The acoustic environment, like every other environment, is being degraded.

But it doesn’t have to be, is Young’s point. We’ve all settled for this, because Steve Jobs said so. (Jobs “appreciated high-res music and listened to vinyl himself,” Young writes. “When we spoke together, he told me his customers were perfectly satisfied with MP3 quality. He had one standard for himself and another for his customers.”) And so: Pono. We might think of it as a kind of organic iTunes. Higher-resolution audio, healthier music. Young spearheaded its development; he got in with heavy business people, heavy tech people. His warlord of a manager, Elliot Roberts, in what seems to me a startling act of managerial magnanimity, was right behind him. The Pono project failed, inevitably (who can beat Apple?), but somehow that is beside the point.

Phil Baker, Pono’s chief developer, is the co-author of To Feel the Music. The book has “Neil” chapters and “Phil” chapters. Baker, on the one hand, writes clear and unexciting prose. “I’ve usually found that working with a small, smart development team is much more effective than working with a large product design organization, particularly when you can build that team with engineers matched to the exact needs of the product being developed.” Indeed. Young, on the other hand, writes books like he makes records with his on-off band Crazy Horse—which is to say, according to a highly evolved and very disciplined aesthetic of half-assedness. Whatever comes out comes out. The drums may sag, the jams may wander, but a zone of bristling and broadly energized possibility is created. Stylistically, To Feel the Music is a more reined-in performance than his previous books, but the old wild sloppiness pops up here and there. “You know, I may end up going to my grave and be banging my head against my gravestone trying to get somebody to understand about what’s happening to music!”

“It is the summit of idleness to deplore the present,” Martin Amis once wrote, “to deplore actuality.” But what if actuality is deplorable? Young is right about our current listening conditions—more than right, he’s prophetically correct—and his mission to improve them, to improve us, has the nobility of true crankdom. He’s certainly not making any money off it.

To Feel the Music is a very odd book. The chapter titled “Our Kickstarter Adventure” (there was a fundraising campaign for Pono in 2014) features a chart that breaks down the number of backers by country: four in Peru, two in Estonia, and so on. But there’s a heart in there somewhere—a big, shaggy, contrarian Neil Young heart, thumping away. We should pay attention. At his website, neilyoungarchives.com, he’s streaming high-res audio right now. Check it out. Compare and contrast. Don’t leave him to bang his head on his own gravestone.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.