The Logical Gymnastics of Shakespeare Biography

The lack of information about the playwright’s private life makes it hard to dispute or even describe his identity. But people keep trying anyway.

It’s a hard life for biographers of Shakespeare, softened only by their royalties. Very little is known about the man himself, and what is known has been in the public domain for a long time. The most recent discovery with any significant relation to his private life (a deposition in a lawsuit contained in the so-called Belott-Mountjoy papers) dates back to 1909. Given that no letters survive and very few documents of a nonofficial nature do either, it is perhaps not surprising that speculation about the bard runs wild. What does at first seem puzzling is why this should so often extend to questioning not so much the verifiable facts of his life (such as his origins in Stratford-upon-Avon and his membership in a leading London theater company) but the authorship of his work. The plays modern readers know as Shakespeare’s were regularly attributed to him not only after his death, but also by a large number of his contemporaries. Since some of these contemporaries—including the cantankerous Ben Jonson—had close connections with the theater, the “anti-Stratfordians,” as those who dispute Shakespeare’s true identity are called, have to imagine some kind of conspiracy of silence for which the motives are not at all clear.

One reason speculation has taken this turn is that people have difficulty reconciling Shakespeare’s relatively modest social background, and the fact that he did not go to university, with the sophistication of his writing. This seems to be part of the stimulus for proposing Christopher Marlowe, who was a Cambridge graduate, or the 17th Earl of Oxford, whose claims to refinement are in his title, as the plays’ real author. While Emilia Bassano, the subject of Elizabeth Winkler’s recent article, “Was Shakespeare a Woman?” is a late entrant in this race, her candidacy appears to have been prompted by similar feelings of wonderment at what one discovers in Shakespeare’s writings, in particular the rare insight into a woman’s feelings. This argument hardly puts Bassano in pole position, but she has at least one obvious advantage over her two male contenders: She lived on for many years after Shakespeare’s death in 1616. That Marlowe was murdered in 1593, and the Earl of Oxford died in 1604, requires their supporters to perform feats of intellectual ingenuity that Winkler is spared.

One of my objections to those who claim that Shakespeare did not write the works attributed to him is that they are obliged to indulge in even more logical gymnastics than the biographers who set out to discover what he was “really like.” The nature of such gymnastics was brilliantly exposed by Samuel Schoenbaum in his 1970 book, Shakespeare’s Lives. In 2012, because Schoenbaum’s lessons did not seem to have been taken on board, I wrote what I hoped would be a small addendum to his work in The Truth About William Shakespeare. I attempted to provide an inventory of some of the devices biographers since Schoenbaum have employed to obscure the fact that they were having to make bricks without straw.

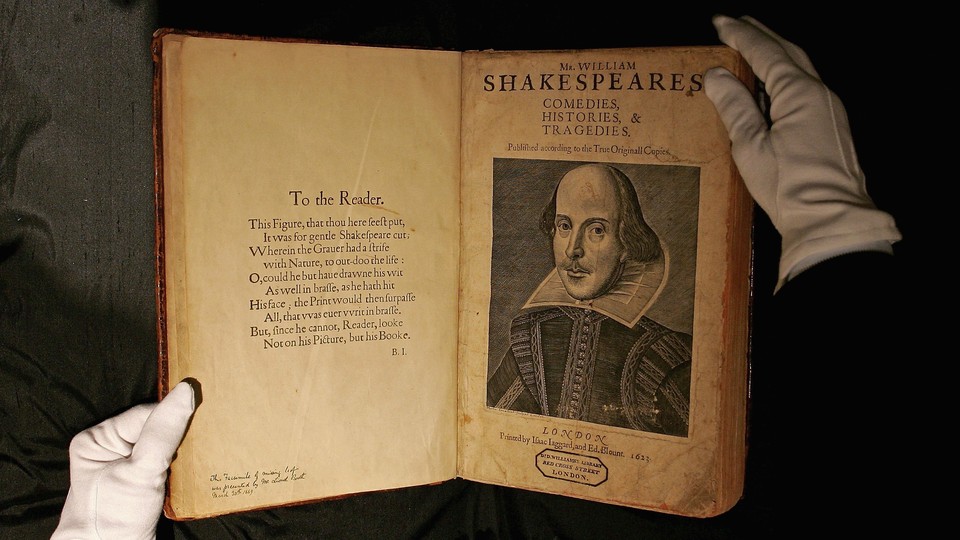

My personal favorite among these strategies, although it is by no means the most prominent, is the argument from absence. For example, a couple of Shakespeare biographers, including the writer Anthony Burgess, have argued that he must have died of syphilis because, in addition to the fact that the signature on his will is spidery and his writings contain numerous allusions to venereal disease, no references to him exist in his doctor son-in-law’s surviving notebooks—a clear indication, according to Burgess, that “decency prevailed over clinical candour.” There are faint echoes of this style of reasoning in Winkler’s enthusiasm for the absence of records showing that Shakespeare was paid for anything he wrote, though the devices she employs, or borrows from her sources, are usually more familiar (and less fun). She says, for instance, that Jonson’s poem “On Poet-Ape,” which satirizes some unidentified and unknown plagiarist, “was likely taking aim at Shakespeare.” But as she goes on to the difficult task of explaining away the contribution Jonson made to the First Folio in 1623, she assumes what was previously only “likely” as an undoubted fact.

Attempting to dispute Winkler’s case at every turn would be wearisome for all concerned. I can only say that reading through Winkler’s description of the arguments the scholar and theater director John Hudson has put forward for Emilia Bassano as the power behind Shakespeare’s pen makes me remember a dream I used to have when I was more directly involved in these matters a few years ago. In it, I had been accused of some unspecified crime, of which any fair-minded review of the evidence showed I was innocent. But as I entered the courtroom, and saw that the jury was composed half of Shakespeare biographers and half of anti-Stratfordians, I knew at once that my goose was cooked.

Why should it matter, many sensible readers will complain, who wrote Shakespeare’s works, as long as we have them? What difference does it make? In his later life, Sigmund Freud, whom Winkler correctly identifies as an anti-Stratfordian, gave an account of how he discovered psychoanalysis, which was adopted by his biographer Ernest Jones and has since convincingly been shown to be wildly inaccurate, if not positively mendacious. In Jacques Lacan & Co., her influential history of psychoanalysis in France, Élisabeth Roudinesco argued that Freud’s invention couldn’t necessarily be opposed to the mere reality of facts; the genuine truth of this story, she concluded, lay in the way the psychoanalytic movement tells itself the initial fantasies of its birth. One or two recent biographers of Shakespeare have flirted with this postmodern notion of origins, but their scholarly instincts are usually too strong for them not to want to tell the truth about the past, if they were only able to discover it.

How a discovery confirming Shakespeare’s identity would change our reading of the plays and poems is impossible to say, but it is hard not to sympathize with D. H. Lawrence when he was introducing a collection of his own poetry and explaining why he felt it necessary to provide a little biographical background. “If we knew a little more of Shakespeare’s self and circumstance,” he wrote, “how much more complete the Sonnets would be to us, how their strange, torn edges would be softened and merged into the whole body!” This seems to me true whether we regard the sonnets as in fact the work of Stratford’s Shakespeare, or of Emilia Bassano.