Remembering Tutankhamun

His most recent 100 years

Gilded wood statuette; my photo, taken at the Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh exhibition, London, November 2019

It’s a small, almost nondescript tomb, containing only four rooms, nothing like its colourful, labyrinthine neighbours. But it’s the one most people know about, because of the ‘wonderful things’ found in it.

Egyptology is celebrating 100 years since the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings, found almost intact and therefore still crammed with thousands of items (5,000 to 6,000, according to Christina Riggs’ Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century; 51 minutes into the audiobook).

Why does this tomb out of so many in Egypt capture the imagination? Why is this the one that gets all the fame?

Well, partly because of those artefacts, of course. The vast majority of tombs were opened and at least partially emptied before modern exploration (many in antiquity). Of the royal burials, even fewer remained. Tutankhamun’s had not entirely escaped – it had been opened and its contents disturbed (and presumably robbed) at least once before 1922. But it contained far more than most.

Moreover, thanks to the dry Luxor environment, in addition to the famous ‘treasures’ we have textiles and even sandals, which pique our emotions and seem more ‘human’ than the gold, whereas the much later royal tombs in the damp delta up north in Tanis contained exquisite metalwork but nothing perishable.

Fortunately, Egyptology had mostly moved beyond ‘treasure hunting’ by 1922 and Tutankhamun’s tomb was carefully documented as it was emptied over 10 years. Thanks to the British team’s arrangements with the London Times, images of the find were seen across the world, giving birth to ‘Tutmania’.

So, most people remember Tutankhamun partly because he (unwittingly) brought ancient Egyptian history alive for a modern audience. And Egyptology pays attention because of the sheer quantity of information that the find made available to us and the fact that such well-preserved royal burials are rare – Tutankhamun’s burial, although it was obviously not ‘typical’ for a king, provides a rare glimpse of what other royal burials may have looked like.

(Even 100 years later, we are still studying and learning from the objects found in the tomb.)

Who was Tutankhamun and why was his burial not like other kings’?

He became king in the aftermath of two decades of religious turmoil. One of his predecessors (who may or may not have been related to him, depending on who you believe) had moved away from the traditional deities and elevated the Aten, the sun disk. This reform seems not to have been widely supported – it lasted only about 15 to 20 years.

Under Tutankhamun’s reign, the traditional deities were restored. We see this transition in the objects from the tomb – decoration reflecting both religious systems, and items that have been changed from one to the other. Even Tutankhamun’s name changed, by the way – he started life as Tutankhaten, named for the Aten (‘the living image of the Aten’); when the traditional religion was restored, and Amun again became the dominant god, this change was reflected in the king’s name.

You can find out more in this 45-minute talk online: Garry Shaw, The Story of Tutankhamun, Egypt Exploration Society, October 2022.

Pharaohs’ tombs in the Valley of the Kings tended to be vast and extensively decorated (I’m generalising about several hundred years here), so Tutankhamun’s is notable (though not unique) for its size and relative lack of decoration. There are various theories about why, but what matters for our purposes here is that the tomb itself is not typical of those immediately preceding and following the religious upheaval. And although we can’t be sure how ‘typical’ the tomb’s contents were, they give us a hint of what might have been in other burials.

Who found the tomb?

The Englishmen Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon get the credit and public glory. But who actually found the tomb?

Carter's (in)famous diary entry for 4 November 1922: ‘First steps of tomb found’; my photo, Excavating the Archive, Weston Library, Oxford, October 2022

Carter’s published account reads: ‘Hardly had I arrived on the work next morning (November 4th) than the unusual silence, due to the stoppage of work, made me realize that something out of the ordinary had happened, and I was greeted by the announcement that a step cut in the rock had been discovered’ (The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen, Howard Carter and AC Mace, 1923).

Egyptology is grappling with its colonialist roots so, while we celebrate all that we’ve learned from Tutankhamun and his tomb, let’s also pause a moment to acknowledge that we’re able to do so thanks to the hard work of very many Egyptian workers.

Although those members of the team never had their names recorded, you can get a glimpse of them, and just how important their role was, in some of the official photos, such as these:

You can read more about the problems of our colonial past in Christina Riggs’ blog, and this picture in the Illustrated London Times of 1923 tells its own story.

Find out more

The excavation records are available online. And if you’re in Oxford (UK) before 5 February 2023, you can see some of the archive in a small free exhibition.

Excavating the Archive, Weston Library, Oxford, October 2022

Entrance to Tutankhamun's tomb and Carter's diary entry, Excavating the Archive, October 2022

The artefacts from the tomb will be on display in the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, which is due to open some time soon. (Many of them used to be displayed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, which is still open and will remain in addition to the Grand Egyptian Museum; one is in Tahrir Square in central Cairo and one is in Giza near the pyramids, on the outskirts of Cairo.)

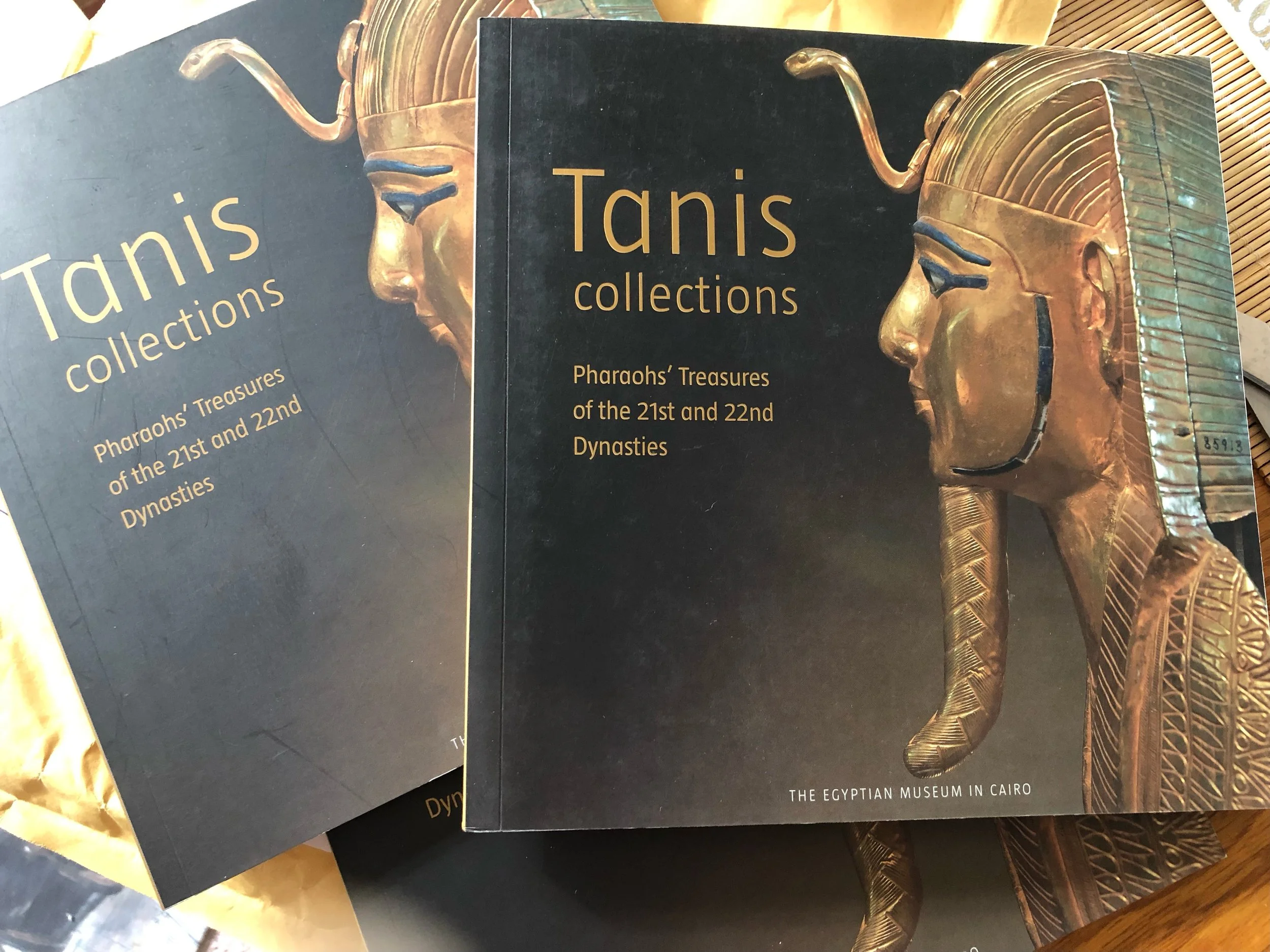

This booklet (which I worked on) is currently available in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo to accompany its Tanis exhibition

Objects from the Tanis royal burials, which date to about 350 years after Tutankhamun, are also on display in Cairo.

PS: Carter famously wrote in his 1923 account that when he first peered into the tomb, Carnarvon asked if he could see anything and he replied, ‘Yes, wonderful things.’ However, it seems that he may not actually have said those words at that moment; they seem to be a bit of poetic licence for the book. There are several accounts of that time, which differ in the detail. Carter’s own journal, written at the time, says, ‘I replied to him Yes, it is wonderful.’

Rest in peace

About 15 years after my first visit, I returned to Tutankhamun’s tomb. As I emerged from the steps into the first chamber, I saw Tutankhamun himself. A shocked tear came to my eye.

He looks so small and fragile. So very young.

Yes, we know him as ‘the boy-king’. Yes, we know he was around 19 when he died.

But I hadn’t realised (or hadn’t remembered?) that, since I’d last been there, Tutankhamun’s mummy had been moved and was now in a glass display case in his tomb. Coming unexpectedly face to face with him drew me up short and made the moment much more emotional than I’d expected.

He was no longer the golden mask of the photos, or the abstract long-past pharaoh who’d been buried with heaps of treasure. Instead, I was forced to acknowledge that he was a human being – and a very young one.

Suddenly, I saw things differently.

This is why I especially appreciated the Garry Shaw Story of Tutankhamun presentation that I mentioned earlier – because Shaw speaks about the boy as a youngster who reigned during a religious revival and had to participate in rituals that he’d never witnessed, for a set of beliefs that he’d never before experienced.

Another of Egyptology’s great debates is around whether human remains should be displayed as museum curiosities. You can read more about the arguments in these articles (which do contain photos of mummies):

https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2010/oct/25/museums-human-remains-display

https://www.honour.org.uk/respect-for-ancient-human-remains-manchester

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/egypt-mummy-museum-ethics

I was glad, however, that I had that unexpected moment because it startled me into a new form of empathy and led me to look and think differently. I stood there for quite a while, gazing entranced into his face, feeling sad for him in so many ways. He wasn’t exactly resting in peace, in that busy room full of chatty tourists.

London, 2019 – statue surrounded by visitors to the exhibition

London 2019

Jo Marchant’s The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut’s Mummy is a moving read, which not only discusses the study of Tutankhamun’s mummy up to 2013 (when the book was published), but also highlights the sad truth that Tutankhamun hasn’t always been treated with the respect we might have expected.