ABC’s Chief National Correspondent Matt Gutman has been in some of the most terrifying and perilous situations a human can experience. As a journalist, he’s been on the ground covering major conflicts everywhere from Israel and Iraq to Syria and Lebanon. In 2016, he was even detained by police and intelligence services while reporting on the health care system in Venezuela. He’s been to the deepest, darkest depths of the ocean in one of the most decorated submersible vehicles in the world. And yet, Gutman’s most trying moment didn’t arrive while he was surrounded by rubble or hunkering down in a war-torn landscape. Instead, it came when he was doing what he does nearly every day: a live read during a television news broadcast.

While reporting on the tragic helicopter crash that claimed the life of the legendary Kobe Bryant, his 13-year-old daughter Gianna, and seven others on January 26, 2020, Gutman made a mistake that would earn him a lengthy suspension from ABC airwaves: He incorrectly reported that all four of Bryant’s children had passed in the accident. Gutman apologized and served his suspension, but his reputation, of course, certainly suffered as a result of his reporting. What most people don’t know, however, is that Gutman’s errant reporting was (at least in part) a result of the fact that he had been suffering a panic attack live on air while delivering his story. In fact, he had been having them quite frequently during his live shots, so it was only a matter of time until something like this happened.

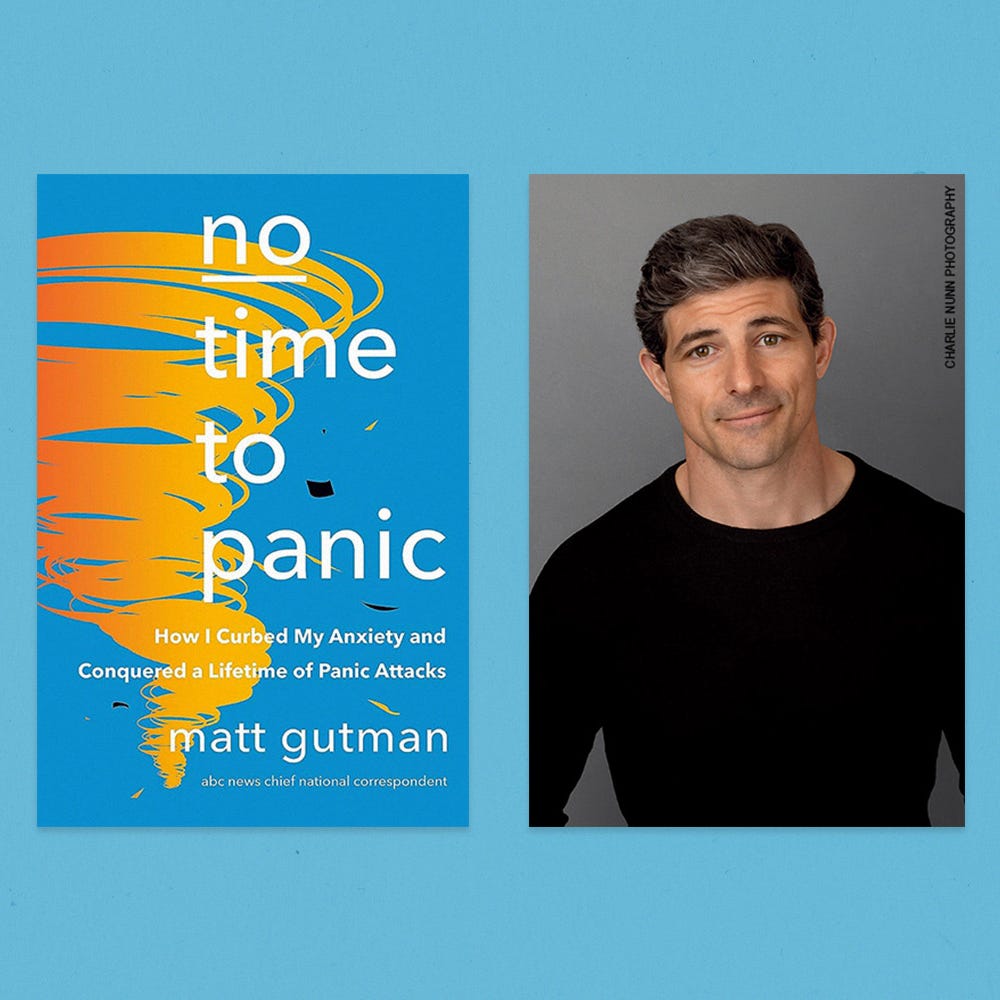

That incident became the impetus for Gutman to look deep within himself, search for answers, and try to find a way to manage his anxiety, all of which he chronicles in his debut memoir, No Time to Panic: How I Curbed My Anxiety and Conquered a Lifetime of Panic Attacks. Heavily researched and expertly reported, Gutman’s memoir is both a poignant personal road map of self-discovery as well as a journey through the history and science of anxiety.

Shondaland recently caught up with the chief national correspondent to discuss living with panic attacks, the unique nature of anxiety, and how he nearly found himself a passenger on the tragic final journey of the OceanGate submersible.

SCOTT NEUMYER: As ABC’s chief national correspondent, you’re always busy and always traveling for stories, even during the global pandemic. How are you holding up after the last few years?

MATT GUTMAN: I had to take a second to think about that, because I thrive in chaos, and my job is basically responding to conflict, bad situations, trauma, disaster, and calamity. So, I think I have a different personal relationship to these kinds of things than a lot of people do. But one thing that really does get me down is climate change, because we’re all just doomed. Politics comes and goes, it changes, but the climate change thing feels like a cultural and generational depressive. I think I’m holding up okay. I’ve spent three years now trying to figure my stuff out and work on not beating myself up as much. In the book, I talk a lot about coming to a truce with my brain because there’s a lot of perfectionism. And of course, the flip side of perfectionism is the constant flavor of failure in your mouth. You just always feel like you’re not living up to other people’s expectations of you, or your own expectations, your mother’s, or whatever. So, that’s the thing that I’ve been working on.

SN: I can tell you that I’ve read basically every book out there about anxiety and panic disorder, and there’s such a broad range of quality. This book, however, feels really hefty while also being very personal and moving. You dig into both of those areas in a way that reminds me of Scott Stossel’s excellent book My Age of Anxiety. Was it important for you as a journalist to make this more than just a memoir and to make this more of a reported piece as well?

MG: I think my comfort zone is the reporting part. I wrote my previous book [The Boys in the Cave: Deep Inside the Impossible Rescue in Thailand] in a month. If there’s one thing I can do, it’s work hard. I was like that as an athlete in high school too. I was a small guy. I was just unbelievably unrelenting and scrappy, and you could not keep me down. And so, I worked, worked, worked. So, it was the same thing with this. I knew I could report this book. I knew there was stuff out there, and I kept digging and finding more stuff. That’s the easy part. The hard part, however … I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to look for a panic attack support group.

SN: Yes! That’s a major part of the book. I was genuinely surprised how difficult it was for you to find one.

MG: I was like, “How was this possible?” We can’t find them. We don’t see them anywhere. I get it, though. They’re hiding. They’re nervous. They’re agoraphobic. Often, they’re not interested in appearing in a room or a chat room or Zoom with hundreds of other people who could scrutinize them, but there are millions of people in this country with full-on panic disorder who need this help and who are not getting it. I don’t know where they are. I still don’t know where they are. Hopefully, this book helps bring them out a little bit, because the people who do turn up to those panic attack support groups that I did find (there was one that I joined), I think they really got help. And then, just being able to talk about it openly was, I think, liberating for these people. So yeah, the reporting part was easy. The memoir part turned out to be much more difficult and much more challenging than I expected.

SN: When you realized how difficult it is to find panic attack support groups, did it make you want to be able to fix that problem with the platform that you have?

MG: I’m gonna echo what’s in the book, but I felt like I was a constituency of more than one. I was like, “Holy s--t, this is endemic.” This is a problem in the fabric of society, and it was underscored by the weakness of the public health sector, both in diagnosing panic attacks and diverting people who are suffering a mental health crisis from the ER.

Since we put this book to bed, there has been a new study that came out, another survey of ERs, that put it [that] 40 percent of people turning up to the ER thinking they’re suffering cardiac arrest, or some sort of cardiac event, are actually having a panic attack. And it said that only 1 percent to 2 percent of everyone who turns up gets treated at the hospital for their mental health crisis. Most people are told that they are not having a heart attack, but not told what it is that they’re suffering from, so they go home to suffer more. And when I heard that, first of all, I guess it was a relief knowing that these horrific manifestations of panic are so common, and that I’m not alone, but it was very disappointing and troubling to know that there’s still much of this and that it could be averted with just a little bit more intervention.

SN: One of the biggest moments in the book is one of the ones that hit me the hardest: when you describe how you decided to finally tell someone about your anxiety and panic attacks instead of hiding it away or trying to keep people from knowing. That was big for you in a lot of ways. Can you describe how much that moment impacted you and what finally talking about your struggles meant to you on this journey?

MG: You mentioned the pandemic, and I was just thinking, “Would I have done it had it not been slightly past the peak in December 2020?” We were all wearing masks. Even in Phoenix, they were wearing masks on the plane because it was mandatory. And you know, was there just a little bit of anonymity in the mask that I couldn’t fully see her face? Well, maybe.

But yeah, it was a pretty pivotal moment, and I think it arrived because it came at one of my lowest lows. I had nothing to lose. It was late in the evening, and I thought, “This person seems lovely. I’m just gonna tell her everything. And what’s the worst that can happen?” And the best thing that could happen was what happened. I’m still in touch with her. It was very freeing. It just felt very seminal. Truly the point at which everything changed for me.

SN: I think about all the things that you’ve done — the cave in Thailand, the submersible, all of your war reporting — and that’s terrifying for me as an anxious person. I can’t even imagine it. Yet you can take those things in stride, but it’s doing your live shot on the news for often a minute or less that makes you panic. That speaks volumes to me about how unique anxiety is for each person. Just the thought of going into a submarine gives me chills, especially in the wake of the OceanGate tragedy.

MG: I was invited to be on that trip and turned them down.

SN: Wait … what?! That specific trip?

MG: Yeah, they asked me because they had an opening, and I couldn’t make it.

SN: Would you have done it?

MG: I don’t think ABC would have let me. We had been talking about it for a couple of years, and I said no for scheduling reasons before, but ABC risk management would have probably gotten the specs of the submersible and said no. I’d been down on the Alvin, which is, like, a [59]-year-old sub. It’s gone for thousands of voyages and is built like a tank. But I don’t think they would have let me on OceanGate.

SN: That’s crazy. I can’t even imagine.

MG: Yeah, it would have been really bad. It would have been bad for my family.

SN: I don’t even know how you do it on a regular submersible like the Alvin. Just the thought of that total loss of control. That’s crazy to me.

MG: You just have to surrender. And people say, “Well, if you can surrender in literally a 9-foot titanium sphere where you have no control, why can’t you surrender in a live shot?” Well, because for me, the physical threats seem manageable and not as imposing as the social threats for some reason. The social threats carry more weight. And maybe that makes sense in a way. More people are destroyed in our day and age by making some sort of faux pas than they are in a catastrophic implosion of a [submersible vehicle].

SN: I suppose that’s what makes anxiety so interesting and so utterly terrifying as well. It can come from anywhere. There are so many people scared of vomiting. Some people are scared of being on live TV. And some people are scared of falling out of a plane. It’s different for everybody.

MG: Absolutely, and I talk about this in the book as well. It’s as unique as a fingerprint. And now I understand all of that.

SN: Having been through all these different experiences trying to understand your anxiety, learning quite a lot from these experiences, if someone came to you and asked, “What are the three best things I can do to help manage my anxiety?” what advice would you give them? (As a non-therapist, of course. Just as a guy who has been through it.)

MG: For anxiety, it’s the super-basic things like exercise, sleep, and nutrition. Or if you wanted to, you could substitute meditation or mindfulness with one of those, but if you can keep those in check, it’s going to help you a lot in the anxiety department. Getting sunlight. Just all the stuff we know that we need to do to keep healthy. Drink less coffee. That we know works. When I drink less coffee, I’m less anxious, but I love coffee.

And for acute panic, honestly, the thing that helped me most is the knowledge that acute panic attacks rarely ever last more than a minute. I can totally get through that. And knowledge like that is the most helpful. The rest is anxiety, which we deal with every day. Anxiety is part of life.

And there’s a mindfulness trick also for acute panic if you’re actually in the midst of it, which is to just think about sensing your five senses. What are you seeing? What are you hearing? What are you smelling? What are you touching? What do you taste? Before a live shot, I’ll just sort of do an inventory and think, “Oh, that’s a pretty tree. Oh, that’s a leaf blower in the back.” I taste a little coffee from earlier, maybe a little garlic from the sandwich. I’m smelling some grass. I’m hearing my team around me. It just takes your mind off of the panic.

SN: What is the best advice you’ve ever received?

MG: My mother says, “Enjoy the passing pageant,” which I think is fantastic advice. For me as a journalist, it sort of encapsulates what I do. It’s like, “Okay, observe this thing.” It’s happening. It’s always marvelous. It’s always incredible. It’s part of life. All of it is material to write about and to think about later. It’s also about being mindful of the thing that’s unfolding in front of you, and it’s about not being too attached to the outcome. Just watch the passing pageant. And that’s going to pass the patch. It’s flowery and beautiful and boisterous and loud right now, but it’ll change. So, it’s really great advice from my mother, who’s never taken it to heart herself. But she was smart enough to give it to me, and I think about it often.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Scott Neumyer is a writer from central New Jersey whose work has been published by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Wall Street Journal, ESPN, GQ, Esquire, The Boston Globe, AARP, Parade magazine, and many more publications. You can follow him @scottneumyer.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY