Before it became the Vietnam War in the 1960s, there was the French Indochina War.

Its defining battle was the siege of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu.

Only 200 Americans were there to witness a battle that would throw the French out of Vietnam in 1954, and lay the foundation for American military involvement in its own Vietnam war a decade later.

One of those Americans was Beckley’s own Jim Rubin, who was just 21 when he was sent to French Indochina.

“That was a harrowing experience for me,” Rubin said. “I don’t think about it much. I try not to. When I got to the Philippines, I had orders. I was to report to the first sergeant. He said, ‘Airman Rubin, you have orders here. You’re going to French Indochina.’ “I didn’t know anything about French Indochina at that time. I was to report to Sgt. Rodriguez. I took my baggage and met Rodriguez. He looked at me and said, ‘There’s your plane.’ That’s all there was to it. I had no briefing, no nothing.”

Rubin climbed onto the plane and saw boxes stacked everywhere. He was aboard a C-47 cargo carrier.

It was just him and the pilots on the plane. The C-47 carrier sat on the runway for awhile in the 100-degree heat.

“On the plane, it was hotter than that,” Rubin said. “I had my fatigues on and they were getting wet with sweat. I finally heard the engines fire up and I said, ‘Hey! We’re actually taking off!’ The ride wasn’t long, but they still had to get up to the right altitude.

“When they hit the altitude, it became freezing cold. I was just shivering from my wet, sweaty fatigues. I’m in an airplane, all by myself, and I have no idea where I’m going. I figured there’d be more of my unit there. It was just me.”

The cargo bay doors opened and Rubin saw napalm burst over the mountain below.

“I was soon taken to a warehouse and told that my job was to supply parts for the B-25 tactical bomber,” Rubin said. “I was to support the French troops that were there.

“I was told that, not far away, was Fort Dien Bien Phu. It was a fortress that the French had created. They felt that it was invincible. No one could touch it.

“They were mistaken.”

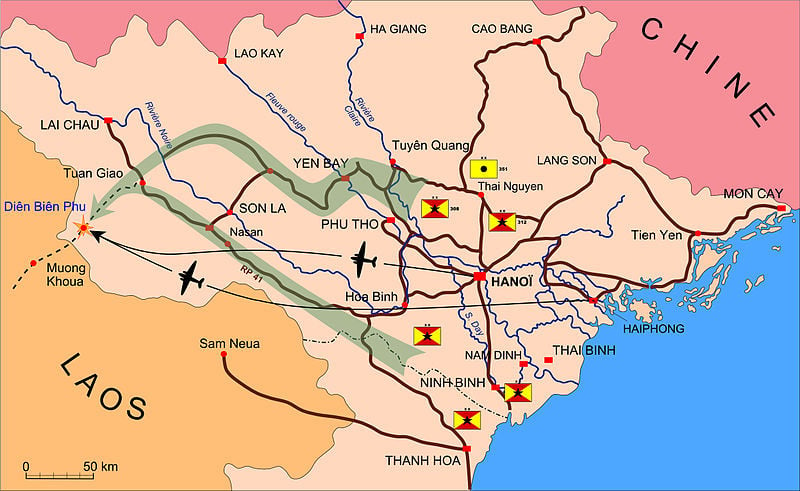

The Communist Viet Minh troops led by Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap were fighting the French. The Viet Minh decided to turn Fort Dien Bien Phu’s greatest strength into a weakness.

“The Viet Minh’s strategy was to surround the valley that Fort Dien Bien Phu sat in,” Rubin said. “The French knew there were no roads up into the mountains. It would be impossible to get artillery up into the mountains. They made paths and they carried the pieces of artillery. They put it together when they got into position.

“The artillery began to aim at the C-47 supply planes and the B-25 bombers. They were hitting them and putting them out of commission. Our job was to sell the French some planes. We sold planes to the French for a dollar apiece. I know because I made the paperwork for the sales.”

Congressional leaders and the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower debated direct military involvement in aiding the beleaguered French garrison. In the end, the United States covertly helped the French by assigning 37 air transport pilots to fly supplies and war materiel into Dien Bien Phu.

Two of those American pilots, James B. McGovern Jr. and his co-pilot, Wallace Buford, were killed.

Planes were crashing left and right as they landed and departed in the middle of the withering Viet Minh artillery fire. The French knew they were in trouble, Rubin said.

“They had 15,000 men in the fort,” he said. “They began to receive casualties. In about a week, they lost 5,000 men.They knew they couldn’t do anything with 10,000 men.They surrendered.

“As part of the surrender, French Indochina was divided along the 17th parallel into North and South Vietnam. I remember that we were right on the parallel. We knew the North Vietnamese would be moving southward soon.”

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu began in January 1954. It was over by May. The impregnable fortress and its 15,000 troops had been defeated by the Viet Minh, which had committed five divisions and 50,000 regular troops to dislodge the French.

To keep the Viet Minh troops from scavenging their supplies, the Americans destroyed anything they could, Rubin said.

“We knew we had to get out of there, so we burned things and blew up things so that the Vietnamese couldn’t take them for their own,” he said. “We got out of there. There was a risk to being there. You didn’t know who was the enemy and who was your friend.

“We were safe down on the flight line where we worked, but we were exposed when we were in the bunker. I remember hearing artillery hitting the mountain and near the base. It made us uneasy at times.”

The base had limited security as the Americans gathered their things and left, Rubin said.

“One of the scariest moments was when a Viet Minh supporter infiltrated our compound,” he said. “Nobody knows how they snuck in.

“They dropped a grenade in our shower room. Their aim was probably to hit some Frenchmen who were in the shower. The only people in the shower were two washwomen. One was killed. I only saw the blood.”

Rubin only spent 88 days in French Indochina, but he saw things he’ll never forget, he said.

“Sometimes we’d have to go out of the perimeter to take out the garbage,” he said. “The dump was off the base. My first experience with the people of French Indochina surprised me. When we were approaching the dump, a throng of women and children came running down the mountain. The driver said, ‘That’s just women and children who go through our garbage.’ “I’m on the back of the weapons carrier tossing garbage out into the dump. Kids were climbing all over the carrier, trying to get the garbage. They didn’t flinch when we scolded them. I watched one woman scrape up food out of the garbage and into a milk carton. I’ll never forget that. I can see that right now. It’ll stick with me for the rest of my days.”

After a tour in the Philippines, Rubin came home and went to college. He became a psychotherapist who specialized in group therapy. He says he worked with people who suffered from severe Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD.

“War is terrible on people,” Rubin said. “It takes the lives of innocent people who shouldn’t be punished.

“People shouldn’t be treated so badly. It goes on in every war.”

• • •

After retirement, things seemed typical for Jim Rubin. He spent time with his family and relaxed.

Things wouldn’t stay so typical, though.

As he went about his life, Rubin would have people come up to him and ask if he was an actor.

He says he never thought much of it, just people being friendly. People kept telling him that he was the spitting image of Abraham Lincoln.

One day at Crossroads Mall, a group was doing a fashion show for old-fashioned clothing. One of the presenters was dressed as Lincoln. Rubin’s daughter told him to go check it out.

When he got to the mall, the presenters jokingly told the Lincoln presenter that he was an impostor. The real Lincoln was standing right in front of them.

Rubin told himself that there may be some substance to what people were saying.

He decided to go to a Lincoln Presenter’s Festival with his family. The festival was sponsoring a Lincoln Look-Alike Contest. Rubin entered and told the story of the little girl who wrote a letter to Lincoln.

He took home third place and a small prize. He still has the check hanging in his home office.

Rubin decided that this was a defining moment for him. He joined the Society of Abraham Lincoln Presenters and showed off the 16th president to children and adults all over the U.S.

He was asked to unveil some special-edition Lincoln pennies in Washington, D.C. He ended up meeting Hollywood star Liam Neeson at a script-reading for the movie “Lincoln” in Hollywood.

Rubin has a room in his home that he’s lovingly nicknamed “The Lincoln Room.” The walls are covered in pictures of the president and a few photos of Rubin himself dressed as Lincoln. Book cases are packed with books about Lincoln and his life.

Rubin says his favorite is a sepia- toned photo of him and his grandson reading together.

The life of Lincoln wouldn’t last forever, though.

Rubin eventually developed neuropathy in his legs, forcing him to use a wheelchair. He eventually shaved Lincoln’s trademark beard and has let his hair gray.

“There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t miss being Lincoln,” Rubin said. “I met a lot of good people and had a lot of good times being the 16th president.”

— E-mail: cneff@register-herald.com

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.