5 Changes in Space Travel Since Yuri Gagarin's Flight

On Yuri's Night, space historians reflect on how far technologies have advanced.

A little over 50 years ago, no one on Earth knew what would happen when a human being was launched into space. That all changed on this day in 1961, when Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet military pilot and cosmonaut, hurtled into orbit aboard Vostok 1.

He circled the Earth once, reporting that he was feeling "excellent" and could see "rivers and folds in the terrain" and different kinds of clouds. "Beautiful" was his simple description of the view. Weightlessness, he said, felt "pleasant." (See pictures of Gagarin's flight.)

In the decades since Gagarin became the first person in space, what began as a politically fraught competition has yielded men on the moon, space walks, and visions of putting people on Mars. Here's a look at some of the important changes in space travel that occurred along the way.

Politics

Gagarin's flight represented a triumph for the Soviet Union during the heat of the Cold War, from which both the U.S. and Russian space programs were born. "The space race was partly about impressing the living daylights out of other nations because the science and technology are closely aligned with military capability," says Roger Launius, senior curator and space historian at the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum.

The Soviets, notes Launius, kept secret for years the fact that Gagarin had to bail out of his spacecraft with a parachute several miles above ground during the landing. The spherical Vostok capsule lacked thrusters to slow it down, and requiring Gagarin to eject before reaching the ground might have meant the mission didn't qualify as the first successful human space flight. "They had no idea what was going to happen—the capsule could have left a big hole in the ground," Launius says. (See pictures of space suit evolution.)

Nowadays the U.S. and Russia collaborate regularly, with cross-training and joint flights to the International Space Station (ISS). The launch pad from which Gagarin took off—Baikonur Cosmodrome in what is now Kazakhstan—is still used today, most recently to send two cosmonauts and a U.S. astronaut to the ISS in March.

Escaping Earth

Gagarin's mission required a rocket that could propel his spacecraft fast enough to sustain a speed of some 17,000 miles per hour (27,359 kilometers an hour), known as orbital velocity. Less than a decade later, NASA's Saturn V rocket achieved escape velocity—the speed required to escape Earth's gravitational pull (25,039 miles per hour or 40,320 kilometers per hour). This milestone made it possible to put men on the moon.

Saturn V stood taller than the Statue of Liberty and generated more power than 85 Hoover Dams. It was a thing of beauty, and resulted in the first human footsteps on extraterrestrial terrain, when Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon in 1969. More Apollo missions followed, and Saturn V took its final bow in 1973, when it launched the Skylab space station into orbit.

Creature Comforts

Gagarin traveled in what was essentially a giant ball and didn't have the capacity to control his spacecraft. If he were to take a tour of the International Space Station today, he might be impressed with the amenities: exercise bikes, barbeque beef brisket—even a choice of toilet papers.

"There wasn't a lot of interest early on in making cosmonauts comfortable—they were there to do a task," says Launius. "It's only with longer-term missions that you have to worry about comfort."

Hence the memorable shower aboard Skylab, NASA's space station during the 1970's and first attempt to test the ability of humans to work and live in space for extended periods. The weight of water and the large equipment required to recycle it, however, proved too much of a burden, says NASA spokesman Jay Bolden, leaving today's space dwellers resorting to "basic squirts of water and soap on washcloths for sponge baths."

Space Medicine

Gagarin's mission lasted 108 minutes, so he didn't have to eat. But the cosmonaut who followed him into space, German Titov, went up for more than a day. People wondered: Would he be able to swallow food?

Today's big questions about space travel and the human body involve bone loss and radiation exposure, but fundamental questions existed even then, notes NASA's chief historian Bill Barry. "People asked if you could swallow without gravity. One of Titov's experiments was to eat something in space," he says.

Another mystery was "space sickness," involving severe nausea. Titov suffered a bad case of it, which worried the Soviets greatly, says Barry. Now it's known to be common among space travelers and even bears a medical name: space adaptation syndrome.

Modern studies focus on the effects of long-term space travel, as eyes turn to Mars and people spend months—even longer than a year in the case of cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov—working in space. "In less than a week we see signs of degradation in the human body," says Launius of the Smithsonian. "I would contend that the real challenge for space travel is biomedical, not technological."

Commercialization

Perhaps the most remarkable change in space travel since Gagarin's historic flight is how routine it's become—and possible for the right price.

Millions of dollars have landed private citizens a seat on Russian spacecraft, though Russia halted its space-tourism role in 2010. (It cited the need to devote its Soyuz capsules to ferrying ISS crew members after NASA ended its space-shuttle program.) Still, so-called space tourism remains on the map as companies like Virgin Galactic race to launch suborbital flights that skirt the edge of space and offer a taste of weightlessness. Virgin's ticket price: $200,000.

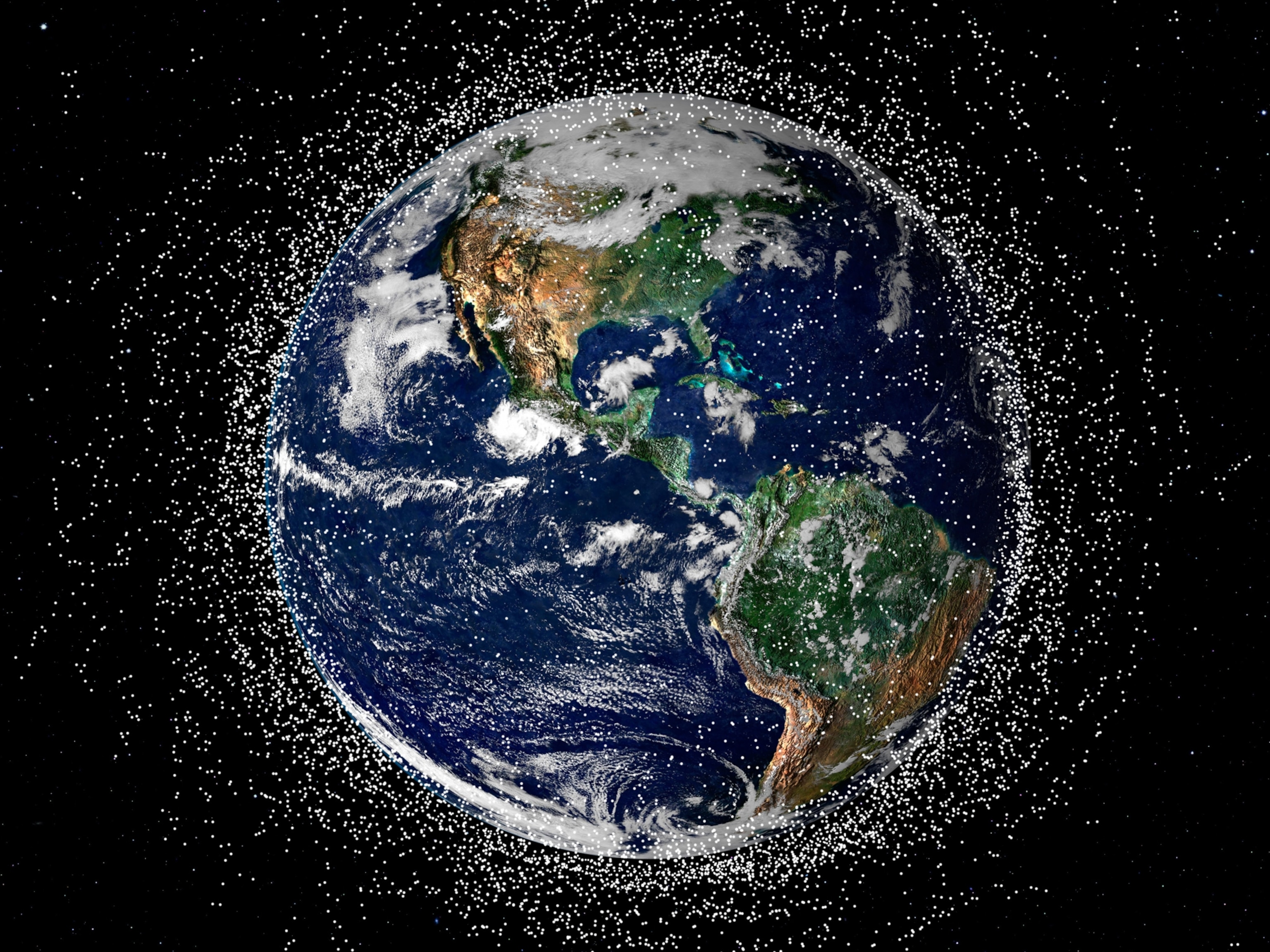

"Not all commercial space activities are about tourism," notes Launius. "Many are about communication, remote sensing, or other activities in which a profit may be made."

One thing that hasn't changed is the view from above. People may no longer stop to take in the video feed from spacecraft floating above Earth, but just listen to Gagarin's conversation with his ground control and you can feel the suspense and awe of seeing the planet from space.

No wonder a great window counts as a major creature comfort for the ISS crew. "The astronauts love to hang out in the station's cupola," with its panoramic views of Earth, says Barry. "I hear they moved an exercise bike there, and one guy likes to hang out and play his guitar."

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Behind the scenes at America’s biggest birding festivalBehind the scenes at America’s biggest birding festival

- How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

Environment

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis beautiful floating flower is wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

History & Culture

- This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?This thriving society vanished into thin air. What happened?

- These were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ eraThese were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ era

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

Science

- Why trigger points cause so much pain—and how you can relieve itWhy trigger points cause so much pain—and how you can relieve it

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

Travel

- 6 of the best active pursuits on Cape Cod and the Islands

- Paid Content

6 of the best active pursuits on Cape Cod and the Islands - The key to better mindfulness may be your public gardenThe key to better mindfulness may be your public garden

- How to spend a weekend in Kitzbühel, Austria

- Paid Content

How to spend a weekend in Kitzbühel, Austria