Herakles & The Hydra: From an Allegorical and a Psychoanalytical Perspective.

Given that Greek mythology offers a plethora of rich, multi layered symbolism,I’d like to provide a critical analysis of Herakles’ Second Labour – the killing of the Lernaean Hydra :firstly, from a psychoanalytical perspective and then from an allegorical one. Furthermore, I will provide a fairly brief argument as to why I think one of these perspectives is more convincing than the other.

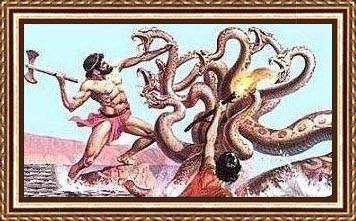

In order to provide a telling analysis, I feel that is important to provide significant details about the narrative of this particular Labour. For his Second Labour, Herakles is instructed to slay the Hydra of Lerna ' a many headed serpent that grew two heads for everyone destroyed' (March, 1998, p. 193) Initially, ' Herakles flushed the Hydra out of its den by shooting it with blazing arrows,' ( Kershaw, 2007,p. 158).

However, he was only able to subdue it as it kept reproducing new heads. Herakles eventually dealt with this deadly foe by quickly slicing off its heads, while his nephew and charioteer, Ioalaus, sealed the wounds with a torch. Herakles made his arrows poisonous by dipping them in the Hydra’s blood.

From a psychoanalytical perspective, I think that the slaying of the Hydra demonstrates symbolically the myriad psychological problems that are often incredibly persistent in the human psyche; e.g anxiety, phobias, obsessions etc. When we don’t get to the root of a problem symptoms invariably persist over time. It appears that as soon as we deal with one problem, two more spring up in its place. Like Herakles, we cannot simply deal with the mere appearance of things. Consequently, we have to work though superficial issues in order to penetrate to the root of the problem. Essentially, we won’t overcome our problems thoroughly, unless they are addressed at the source – i.e by getting to the heart of the matter in hand. Perhaps, the fact that one of the Hydra’s heads is immortal, suggests symbolically that we will always face challenges in life:

' Evil can never be completely or forever eradicated. Only controlled, contained and constantly kept in check.' ( Diamond ,2009)

Similar to Herakles, we seem to face an endless array of tasks in life that cannot be easily accomplished. It takes intense will power, determination, (fire, in the case of Herakles) and possibly extensive therapy. to take on our fears and discern the root of a problem:

'Human existence and the individuation process itself demand such heroic strength, stamina and courage from each of us in various ways.' ( Diamond, 2009, )

The two giant figures of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud ( 1856 – 1937) and Carl Jung ( 1875 – 1961) saw myths, like the illuminating Hydra task, as pertaining to vital aspects of the human psyche: 'For Freud, myth presents dark irrational things that, once they are explained, lose their menace; they evaporate. For Jung these dark creatures are part of our life which we must face and subdue.' ( Taplin, 1989, p 108)

Freud and Jung both believed that by courageously facing our inner demons, so to speak, we return psychically strengthened; more whole; more enlightened . Both Titans of psychoanalysis were all too aware of ' a dark beast which threatens to consume innocence and rationality' ( Taplin, 1989,p. 109) It is perhaps of interest that this personification of the darker side of the human personality parallels allegorical notions which I will discuss later.

In my view, Herakles tasks, including the killing of the Lernean Hydra, can be viewed as representing psychological development. Perhaps, the fact that Herakles dips his arrows in the poisonous blood of the Hydra suggests,( if we employ a psychoanalytical approach), that we can take something and learn from every experience in life.

Can Herakles’ Second Labour be regarded as an allegory that represents the triumph of reason over passion or the triumph of virtue over vice? Perhaps it can be viewed as the triumph of Greek civilization over the 'hellish' realms of barbarism. Perhaps, the slaying of the Hydra can be regarded not merely as an epic battle against a particularly vicious monster, but as one man triumphing over adversity through courage and resilience. Perhaps, the Second Labour, like several of the others, can be viewed as a symbol or metaphor for courageously facing life and its adversities and being able to triumph over them? In this sense it has many parallels with the psychoanalytical perspective. Consequently, there appears to be a number of allegorical aspects to Herakles’ Second Labour which emphasise the inherent values of both moral and physical courage The successful employment of Herakles' mighty club to thwart the Hydra could be viewed as representing rationality/ civilisation triumphing over barbarism in the form of the philosopher who thwarts the Hydra of desire, It seems that this allegorical notion of Herakles was very popular in Renaissance art:

' The allegorical conception of Hercules so popular in Renaissance literature underlies many of his appearances in the visual arts. Overtly allegorical, for example, is Rubens’ club wielding Heroic Virtue ( "Hercules Over coming Discord” '( Stafford, 2012, p. 213.)

Furthermore, Herakles can be viewed as an aesthetically pleasing symbol of physical courage, 'he can exhibit a dramatically lit, muscular physique, framed by the lion - skin cloak, as in Guido Reni’s image of him battering the multi - headed Hydra with his club,' ( Kershaw, 2007 p. 188). During the Renaissance he was certainly viewed by European nobility, ' as a champion of physical strength and moral integrity,'( Furlotti, 2008, p. 240)

On the other hand, the Second Labour could be seen as an allegory of religious inspired virtue against vice. From a Christian perspective, ' this labour can be interpreted allegorically, as the fight of the virtuous against the all consuming’ delights of the flesh’, the three heads being the vices of sloth, gluttony and extravagance, against which the only remedy is to surround oneself with the ‘ fire’ of an ascetic life.' ( Stafford, 2012, p. 207 - 208)

From an allegorical perspective, Herakles courageous victories over monsters and other dangerous enemies could and were interpreted as Christ like mastery of earthly evils. According to the Elizabethan scholar Francis Bacon, who exalts Herakles with strong biblical language, 'Hercules seems to represent an image of the divine Word, hastening in the flesh, as it were in a fragile vessel, to the redemption of the human race.'( Bacon, 1609, chapter 26)

It is noteworthy that the Christian allegorical interpretation of Herakles’ feats have persisted through time:'With the rise of Christianity in the first few centuries AD Herakles’ cult inevitably died, but the hero himself continued to fascinate writers and artist, who romanticized him as a medieval knight, allegorized him as the incarnation of Christian virtue, and even proclaimed him as a prototype of Christ.” ( Stafford, 2012, Foreward xxv)

It seems to me that there are several key similarities between Herakles and Christ. Both were believed to be born from a mystical union of an immortal god and a virgin who was mortal. Both suffered an agonizing death which was followed by the guarantee of eternal life:'In France…Hercules encounters with monsters were presented as Christ’s battle against evil in Chretein le Gouay’s Ovid Moralise ( 1340), a version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses interpreted for a Christian readership.' ( Stafford, 2012, p 208.)

The allegorical perspective, particularly in its blatantly Christian aspects, held sway over many people: ' With such a life of effort and dedication. And a death that led to immortality, it is not surprising that Heracles came to be closely linked with the Christian saints, and even to be seen as symbolically related to Christ’( March, 1998, p 197.)

Nevertheless, ultimately, I find the Manichean struggle implicit in the allegorical perspective ( particularly the Christian perspective) to be a rather simplistic and antiquated approach to viewing Herakles’ Labours. Perhaps this approach is relevant to more traditional epochs. I prefer the modern take on the myths, supplied by psychoanalysis, as I feel that it offers an insight into the human condition in contemporary times. In my eyes, psychoanalysis is key to understanding important aspect of the human condition. It is much more concerned with how human beings understand and relate to each other in the modern world, than potentially spurious claims about religious generated absolutist notions of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. In addition to this, I feel that psychoanalysis whilst clearly recognizing evil ,like the allegorical perspective, provides a more nuanced, more scientific/ empirical understanding of it: via Freud’s reference to the ‘Id’ ( basic instinctual drives & impulses) and Jung’s Shadow ( the primordial aspect of our being). Indeed Jung. “ intentionally employed the more mundane, banal, less esoteric or metaphysical, and therefore more rational terminology – the ‘ shadow’ and the ‘ unconscious’ instead of the traditional religious language of god, devil, daimon or mana.” ( Diamond , 2012.

It can be argued that, the psychoanalytical interpretation of Herakles' Second Labour seems to suggest a novel way of becoming a more whole/ integrated person. Unlike the allegorical interpretation, it doesn’t uphold a strict dichotomy in the way say the time honoured binary - virtue/ vice does.

However, it would be foolhardy to reduce myth to a purely psychoanalytical reading as it is multilayered with many possible interpretations. The multiple perspectives employed have indeed, ' shed a great deal of light on both the myths and those who interpret them.' ( Kershaw, 2007, p.466.)

Nevertheless, if “ Greek mythology is fundamentally about human beings’”( Kershaw, 2007, p 21) then I feel that a predominantly psychoanalytical reading of texts concerning myth can help us to understand ourselves and others in a much more comprehensive manner than outdated religious notions or rigid, stereotypical interpretations ( heroes/ villains; virtue/ vice; good; evil) from antiquity allow.

To conclude, I’ll leave the final thoughts on this matter to Oliver Taplin and his insighcommentary on the importance of the godfather of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud.:

'Freud saw myths, like dreams, as a coded expression of the unconscious; unlike dreams, however, they are shared in public. If they can be understood, he claims, we gain access to that level of the human mind which is the key to mental health. Myths are a clue to our psychic history.' ( Taplin, 1989, p. 103).

Bibliography:

1.) Bacon, F. ( 1609) On The Wisdom Of The Ancients, Longman, London.

2.)Diamond, S ( 2009) Why Myths Still Matters: Hercules and His Twelve Healing Labours - ‘ Rage Evil and Redemption: Part 1’, Psychology Today[Online], available at http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/evildeeds200910.( Accessed 6 July 2019)

3.)Diamond, S. ( 2012) Essential Secrets of Psychotherapy: What is the “ Shadow ”? Psychology Today [ Online], available at http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/essential -secrets-psychotherapy-what-is-the-shadow?2012 ( Accessed 10 November 2016)

4.) Furlotti, B (2008) Art of Mantua: Power & Patronage in the Renaissance,Los Angeles: Getty Publications

5.)Kershaw, S. ( 2007) A Brief Guide To The Greek Myths , London: Robinson.

6.)March, J. ( 1998) Dictionary of Classical Mythology, London: Cassell.

7.)Stafford, E ( 2012) Herakles, Oxon, Routledge.

8.) Taplin, O. ( 1989) Greek Fire, London: Jonathan Cape.

Fue a Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

4yvery good

Professional Freelancer at Fiverr

4yhttps://bit.ly/2XQuFCN