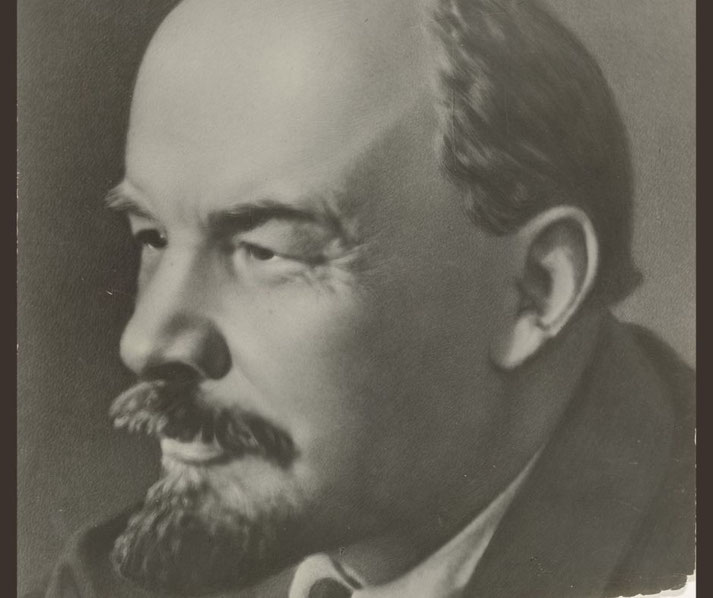

From exile to power: The revolutionary journey of Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin is a man who played an incalculably important role in shaping the socio-political landscape of the 20th century.

Revered by some as a champion of the proletariat and reviled by others as a ruthless dictator, there are few figures in history who have sparked as much debate or admiration as Lenin.

As the principal architect of the October Revolution of 1917 and the first head of the Soviet state, Lenin's actions had far-reaching consequences that continue to resonate in contemporary political discourse.

This is the story of Vladimir Lenin, the man who became a revolution.

Lenin's early life

Lenin was born into a comfortable middle-class family in Simbirsk, Russia, on April 22, 1870.

He was the third of six children and was brought up in an atmosphere of intellectual stimulation and moral rigor.

His parents, Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov and Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova, were both educators who instilled in their children a love for knowledge.

As a result, Lenin excelled in school and showed a particular aptitude for Latin and Greek.

The quiet, bookish boy seemed destined for a career in academia, like his father.

However, a series of events in his teenage years would dramatically alter this trajectory.

In 1887, Lenin's older brother, Alexander Ulyanov, was arrested and executed for conspiring to assassinate Tsar Alexander III.

This personal tragedy profoundly impacted Lenin: sharpening his awareness of the political injustices within the Tsarist autocracy.

Following the death of his brother, Lenin began to engage more deeply with radical political literature, particularly the works of Karl Marx.

He enrolled at Kazan University in 1887 to study law, but was expelled a few months later due to his involvement in student protests.

Becoming a political radical

Vladimir Lenin's political ideology is known as Leninism, which is a significant offshoot of classical Marxism.

Lenin spent many of his early years rigorously studying Marx and Engels, interpreting their theories in the context of late 19th century Russia.

At the time, Russia was a largely agrarian society that bore little resemblance to the industrialized Western Europe Marx wrote about.

At the heart of Lenin's ideology was his belief in the vanguard party's role - a group of professional revolutionaries that would lead the working class in their struggle against the bourgeois.

He firmly believed that the working class couldn't achieve revolutionary consciousness on their own, primarily due to the societal and economic conditions they lived in.

This was a significant departure from classical Marxism, which predicted a spontaneous uprising of the proletariat.

His insistence on the need for an organized, hierarchically structured party would later become a defining characteristic of Bolshevik tactics and Soviet politics.

Lenin's revolutionary activities before 1917

The years leading up to 1917 were a time of intense political activity for Vladimir Lenin.

After his expulsion from Kazan University, Lenin continued his study of law independently, passing his exams and gaining a degree.

But his true passion lay in political activism. During the 1890s, he moved to St. Petersburg, where he became increasingly involved in revolutionary circles.

He spent much of his time disseminating Marxist literature and organizing workers.

However, his politically dissident activities eventually led to his arrest and subsequent exile to Siberia in 1895.

In Siberia, Lenin married Nadezhda Krupskaya, a fellow Marxist revolutionary.

Despite the harsh conditions, Lenin's time in exile proved highly productive.

It was during this period that he wrote "The Development of Capitalism in Russia," outlining his observations on the growth of capitalism in the largely agrarian country.

Then, following his release from exile in 1900, Lenin lived in various European cities including Munich, London, and Geneva.

It was during this time that he became a leading figure in the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

The party, however, was deeply divided over questions of membership and organization, leading to a split during the party congress of 1903.

Lenin's faction, advocating for a smaller, more disciplined party of professional revolutionaries, became known as the Bolsheviks, or 'majoritarians'.

The more moderate faction, favoring a broader, less centralized party, became the Mensheviks, or 'minoritarians'.

Despite the ironically misleading names (the Mensheviks were actually more numerous), Lenin led the Bolsheviks with an unwavering belief in the revolutionary potential of the proletariat.

His writings from this period, particularly "What is to be Done?" (1902), highlight his vision of the party as a vanguard leading the proletariat towards revolution.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks played an active but ultimately unsuccessful role in the 1905 Russian Revolution.

This was a mass uprising triggered by the Russo-Japanese War's hardships and the Tsarist autocracy's inefficiency.

However, the revolution failed to overthrow the Tsar. Regardless, it was a crucial learning experience for Lenin and his comrades.

It reinforced their conviction that only a well-organized, disciplined party could lead a successful revolution.

Then, as World War I raged across Europe, Lenin found himself in Switzerland, cut off from events in Russia.

But he continued his work, critiquing the war as an imperialist conflict and urging workers worldwide to turn the war into a revolutionary civil war.

By the time the February Revolution erupted in 1917, Lenin was prepared. He had spent years developing his revolutionary theories, building a party, and waiting for the right moment.

And that moment was fast approaching.

The February Revolution and Lenin's return

The February Revolution of 1917, triggered by a combination of economic hardship caused by World War I and growing public discontent with the autocratic rule of Tsar Nicholas II, broke out.

It was a spontaneous uprising: a mass demonstration that evolved into an insurrection.

While Lenin was not present in Russia during the February Revolution, the event created an opportunity that Lenin was quick to grasp.

Arranging his return to Russia was not straightforward, given that Europe was in the grip of World War I, and travel was severely restricted.

In a move that sparked controversy, Lenin secured passage through Germany, a country which was at war with Russia, in a sealed train.

This passage was reportedly allowed by the German government, which hoped that Lenin's return might cause further destabilization in Russia and thus weaken their enemy.

Lenin arrived at the Finland Station in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) on April 16, 1917.

He was greeted by a crowd of supporters, to whom he delivered a speech, outlining his 'April Theses'.

This document was a radical piece of propaganda that criticized the Provisional Government and the war effort.

It called for no support for the Provisional Government and urged the transfer of power to the Soviets: the councils of workers and soldiers.

These ideas were initially met with opposition within the Bolshevik Party and were considered too radical by many; but Lenin stood firm.

In the months that followed, the situation in Russia became increasingly chaotic.

The Provisional Government continued the war effort, and economic conditions worsened.

Discontent among the workers and soldiers grew, and support for the Bolsheviks, with their clear and radical solutions to the crises, began to swell.

The October Revolution

The Provisional Government, under the leadership of Alexander Kerensky, was unable to address the growing economic crisis.

What is more, they failed to pull Russia out of the war, leading to widespread discontent.

The Bolsheviks, under Lenin's leadership, seized this opportunity to garner support for their cause.

Their slogans—"Peace, Land, Bread" and "All Power to the Soviets"—resonated with the war-weary soldiers, the peasants yearning for land, and the urban workers suffering from food shortages.

By the time the October Revolution began, the Bolsheviks had gained majority control in the Petrograd and Moscow Soviets.

Crucially this included their armed wings: the Red Guards.

Lenin, recognizing the precarious nature of the Provisional Government's position, began to push for an armed insurrection.

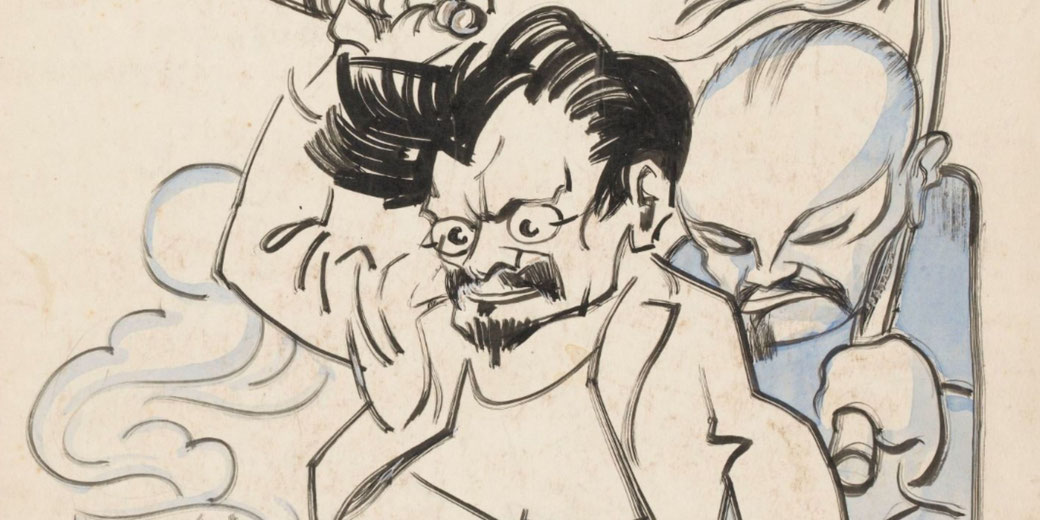

Despite some disagreement within the Bolshevik leadership, notably from Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, Lenin's call to arms prevailed.

Eventually, the insurrection began on October 25, 1917 (Julian calendar; November 7, 1917, in the Gregorian calendar), led by a Military Revolutionary Committee headed by Leon Trotsky.

The Red Guards and the sailors of Kronstadt took key positions across Petrograd with little resistance.

By doing this, they effectively took control of the city.

The Provisional Government's headquarters, the Winter Palace, was then besieged and captured.

This was the end of Kerensky's government.

A day after the insurrection, the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, with a Bolshevik majority, approved the overthrow of the Provisional Government.

Lenin was then elected as the chairman of the newly formed government—the Council of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom).

Lenin in power

Vladimir Lenin's rule lasted from the October Revolution in 1917 until his health started deteriorating in 1922.

During this time, Lenin managed to lay the foundations for a socialist state while grappling with the repercussions of a ruinous civil war.

From the onset, the country was gripped by economic turmoil and the ongoing participation in World War I was taking a toll on the populace.

One of Lenin's first acts as leader was to honor the Bolshevik pledge of "Peace, Land, and Bread."

The Decree on Peace led to the negotiations that resulted in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, which finally ended Russia's involvement in World War I.

Simultaneously, the Decree on Land was issued, redistributing land from nobility and the Orthodox Church to the peasantry.

The government also nationalized industry and banks, signaling a significant shift towards a centrally planned economy.

However, these revolutionary transformations were not universally welcomed and led to the outbreak of the Russian Civil War in 1918.

In this conflict, the armed forces of the "Reds" (Bolsheviks) were pitted against the "Whites"—a loose coalition of anti-Bolshevik forces comprising monarchists, conservatives, liberals, and socialists.

However, Russia was not in a strong economic position to survive a war like this.

So, in a desperate attempt to manage the wartime economy, Lenin introduced "War Communism".

This was a policy that involved the requisition of grain from peasants, the nationalization of industry, and the abolition of the market economy.

Although these measures helped sustain the Red Army, they also led to economic hardship for many.

In fact, it led to numerous peasant uprisings and worker strikes: the people that the Bolsheviks had sought to support the most.

In the face of these challenges, the Bolsheviks still managed to emerge victorious in the Civil War by 1922.

But the victory came at a high cost, with millions dead and the economy in ruins.

In response, Lenin had then introduced the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1921.

The NEP allowed for some private enterprise and market practices to stimulate the economy.

It represented Lenin's pragmatic approach to governance. It ultimately demonstrated his willingness to adjust his policies according to the needs and realities of the time.

Declining health and death

The final years of Lenin's life were dominated by failing health and a growing sense of his impending mortality.

This created a difficult period of uncertainty for the nascent Soviet state.

Lenin's health troubles began in May 1922 when he suffered the first of three debilitating strokes.

It resulted in a loss of speech which severely impaired his ability to work. Despite this, he returned to work in a limited capacity by the end of the summer.

However, his return was short-lived, as he suffered a second stroke in December of the same year.

Understandably, this further diminished his capacity to engage in the day-to-day affairs of government.

During his periods of illness and recovery, Lenin became increasingly aware of the power struggle that was beginning to take shape among his potential successors.

He was particularly alarmed by the growing rift between Joseph Stalin, then General Secretary of the Communist Party, and Leon Trotsky, the Commissar for War.

In an attempt to smooth the future transition of power, Lenin dictated a series of notes and letters, later known as his "Testament," where he commented on the skills and drawbacks of his likely successors and expressed concern over the party's future direction.

Lenin's third and final stroke in March 1923 left him completely debilitated, robbing him of speech and confining him to bed.

His active participation in politics effectively ended, and he spent the last months of his life in semi-seclusion at his estate in Gorki, just outside of Moscow.

On January 21, 1924, Vladimir Lenin passed away. The Soviet government declared a period of mourning, and his body was embalmed and placed in a mausoleum in Moscow's Red Square, where it remains to this day.

How should we remember Lenin?

In the immediate aftermath of Lenin's death, he was canonized as a revolutionary saint in the Soviet Union.

Several countries followed the Leninist path to socialism throughout the 20th century, including China, Cuba, and Vietnam.

However, Lenin's legacy is deeply controversial. Critics argue that his vision of a vanguard-led revolution and a proletarian dictatorship laid the groundwork for an authoritarian regime.

They contend that his policies, particularly during the Civil War and the implementation of War Communism, resulted in economic hardship, civil rights abuses, and the loss of millions of lives.

Moreover, his testament's disregarding and the subsequent consolidation of power by Joseph Stalin marked the beginning of a period of extreme totalitarianism and purges, often referred to as Stalinism.

While Lenin had expressed concerns about Stalin's power, his model of centralized power arguably paved the way for such an authoritarian rule.

Despite these controversies, Lenin's ideas and actions have left a lasting imprint on the world, making him a central figure in the history of the 20th century.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.