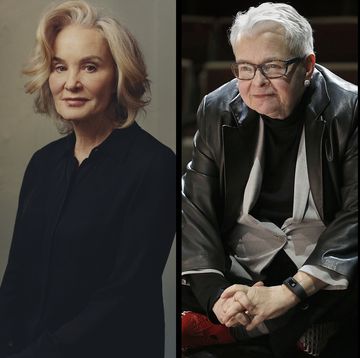

To say that Jasper Johns is ambivalent about having to discuss the intentions or meanings behind his art would imply that there is some part of it he doesn’t find distasteful. Johns has always been reluctant (and unwilling) to “explain” himself or his work. He isn’t humorless; in fact, he’s the opposite. He has just never been interested in the public parts of being an artist that involve submitting himself as a specimen for examination. Johns has developed a Zen-like threshold for uncomfortable silences—a skill that, at 91, he has refined to an art in itself. (In the 1990s, he had a rubber stamp made that said “Regrets, Jasper Johns,” which he’d use to decline invitations and requests; the stamp found its way into a series of works shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 2014 under the title “Regrets.”) During the pandemic, Johns took the opportunity at his estate in Sharon, Connecticut, to toil away unfettered on the multiple projects he always has going—or at least less fettered than usual. “I was able to work in the studio without as much interruption as typically occurs,” Johns says. “Most of the time was spent on a painting and a few drawings and a print that took more time than usual to resolve and is now, finally, being printed—I hope!”

The respite is about to end. On September 29, “Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror,” the most comprehensive retrospective ever of Johns’s work, is set to open simultaneously at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The exhibition will showcase nearly 500 pieces across the two institutions, with each museum exploring the Johns canon through“echoed” or “mirrored” lenses. The Whitney and the PMA will present different programs connected by “chapters” that are built around loose themes and motifs and incorporate iconic works like his American flag and map paintings, bronze sculptures of objects like beer cans and lightbulbs, and a vast collection of monotypes and prints. Entire galleries will be devoted to restagings of two of Johns’s early shows at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York, where some of those pivotal works were first unveiled. The exhibition will also include previously unseen paintings, drawings, and prints, as well as new works completed within the last year.

At various times, Johns has been described as America’s greatest, most prodigious, and most expensive living artist. Starting in the 1950s, his flags, maps, targets, and stenciled numbers and letters, many of which were rendered in encaustic (a mix of hot wax and pigment), explored the nature of representation, language, repetition, and meaning. His work seemed to foreground process, or the making of art, with an almost eerie sense of detachment and anticipated movements like Pop art, conceptualism, and minimalism. It also signaled a move away from the more gestural painting of Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. In 1964, he jotted his recipe for success in a sketchbook: “Take an object / Do something to it / Do something else to it. [Repeat.]” The fact that he chose to do that with symbols of American national and political power and systems of enforced logic, like targets, numbers, and letters, was what made his work so potent. The gaze of the art world was shifting to New York, and Johns and his close friend and fellow artist Robert Rauschenberg, along with choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage, were part of a pioneering new American avant-garde. (Fittingly, Ralph Lauren, who has engaged with Americana and American iconography in more ways than any other designer, is a lead sponsor of the Whitney portion of “Mind/Mirror.” “The American dream has always been at the root of my inspiration,” Lauren says. “The cowboy stood for a person who wasn’t afraid of hard work, wore his jeans until they wore out, and then patched them. That’s at the heart of the American values that I’ve always celebrated and still believe in.”)

While Johns’s popularity has waxed and waned, the market for his work has not. In 1980, the Whitney purchased Johns’s Three Flags for $1 million, then a record price for the work of a living artist. In 1988, Johns’s 1959 painting False Start was auctioned at Sotheby’s in New York for $17 million, topping a record Johns himself had set the previous night with his 1958 painting White Flag, which went for $7 million. Another flag painting was sold privately to hedge-fund billionaire Steven A. Cohen in 2010 for a reported $110 million.

Nevertheless, “Mind/Mirror” comes at a curious juncture in American art. In recent years, much of the emphasis in the nation’s major institutions has begun to veer away from celebrating the contributions of artists like Johns—part of the established narrative of art history, his place firmly entrenched—and toward a reappraisal of that narrative itself, which has historically excluded so many. In addition, some of the works for which Johns is best known, like his flag paintings, also resonate differently at a moment when the fault lines in the union that the flag is supposed to represent are so apparent. The flag itself was wielded by the throng that led the siege on the Capitol in Washington, D.C., on January 6; it’s hard to look at Johns’s maps now and not think of political maps, with red and blue states and district lines that have been redrawn, or “heat” maps designed to diagram the spread of Covid-19 variants. Johns says he has tried to keep up with the news, even when it’s been tempting to look away. “There were specific events—those that took place on January 6, the presidential inauguration, the Supreme Court confirmation hearings—that I watched with interest,” he offers. “Generally, it has been difficult and discouraging to follow current events.”

Planning for “Mind/Mirror” began in 2016; it was originally slated to open last year before it was pushed back because of the pandemic. “We tried to do a show that in its very structure replicates some basic procedures at play in Johns’s oeuvre,” says Carlos Basualdo, the PMA’s senior curator of contemporary art, who oversaw the exhibition with Scott Rothkopf, the Whitney’s senior deputy director and chief curator. “The work is inquisitive and poses thoughtful questions that are very urgent. What is the relation between signs and meaning? What is memory? What is truth?”

“The biggest surprise for me was to confront head-on Jasper’ s incredible capacity for reinvention,” says Rothkopf. “History has a way of smoothing out an artist’s work or making certain shifts look inevitable. But Jasper has never been on autopilot.”

At this stage, Johns has seen his art analyzed, organized, and curated in a multitude of ways; the Whitney even held its own retrospective back in 1977. But he finds the format of this new show intriguing. “I have never seen an exhibition that was divided between two different cities, so this is going to seem odd in that respect,” he says. “For an artist, I suppose, any exhibition of his or her work may seem retrospective and too familiar.”

Johns was born in Augusta, Georgia. After his parents divorced when he was a toddler, he was sent to live with his paternal grandfather in Allendale, South Carolina. He had infrequent contact with both his parents for most of his childhood. His father’s mother had passed away, and Johns’s grandfather had remarried, but his late grandmother had an interest in art. Her paintings were all over the house. In a group of works from the mid-1990s, Johns included a floor plan, drawn from memory, of his grandfather’s home. “I don’t remember what my idea of being an artist consisted of as a child, but I knew that to be one, I would need to be somewhere other than where I was,” Johns says.“That idea appealed to me and contributed to my determination to become one. Even as a teenager, I knew little about the United States other than having learned their names in grammar school, but ‘New York’ seemed exotic and about as far away as one might get.”

By 1953, Johns had made it there. He’d first come to New York in 1948 to attend Parsons but was drafted into the Army during the Korean War. He served for two years, with a six-month station in Sendai, Japan, before being discharged. Not long after his return, he met Rauschenberg, with whom he developed a particularly tight bond; they ended up working out of the same building on Pearl Street in the Financial District. They also collaborated with Cunningham and Cage on performance projects. But things, for Johns, were not going well. One day in 1954, Johns decided that there was a difference between wanting to be an artist and actually being one, so he destroyed all of his work. Soon after, he had a dream about an American flag. The next morning, he stretched some bedsheets across a wooden frame and began to paint that flag—at first with the oil paint he had on hand, but later switching to encaustic, which was used in ancient Egypt to create portraits of the dead and had the added benefit of drying quickly.

Johns has said that part of what he liked about the flag was that it was already designed—it was a “ready-made” image in the vein of the manufactured objects like bicycle wheels and urinals that Marcel Duchamp incorporated into his art—so he didn’t have to create it. Johns has expressed similar feelings about his use of other recurring images like skeletons, catenary lines, and rulers: They were “things the mind already knows,” and any deeper reading or attempt to decode or organize them into some sort of language is about not him but us.

Among the more recent works in “Mind/Mirror” are selections from a series of paintings, drawings, and monotypes that Johns made between 2014 and 2018, some of which were titled or inscribed with variations of the phrase “Farley Breaks Down After Larry Burrows.” The primary source material was a 1965 picture of a marine in Vietnam, Lance Corporal James Farley, that appeared in Life magazine. The image, taken by photojournalist Larry Burrows, captured Farley hunched over a stack of artillery cases, holding his head and covering his face with his hands after a catastrophic mission. It’s one that Johns returns to over and over, rendering it in different media, abstracting it, transforming it into an array of shapes and forms. The soldier, Farley, eventually made it home from the war; the photographer, Burrows, was killed six years later while covering the conflict in Laos. But in Johns’s art, their grief, humanity, fates, and purposes are inextricably bound—in many ways with Johns’s and our own.

Rothkopf recalls meeting with Johns at the artist’s home in Connecticut in the early stages of organizing “Mind/Mirror.” At one point, Rothkopf mentioned that the exhibition, then scheduled to open in 2020, would be up in time for Johns’s 90th birthday, to which Johns responded: “The possibility of my future existence has nothing to do with this show.” Rothkopf now says, “I’m half Jasper’s age, so it’s hard for me to imagine what it feels like to be 91, but I have learned from him not to take one’s own future for granted.”

I ask Johns if he ever had a Plan B if becoming an artist didn’t work out. “No,” he says. “Even though so much seems to happen by chance, I don’t think that I ever considered an alternative.” He adds: “Of course, always looming was the possibility of failure.”

This article originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of Harper's BAZAAR, available on newsstands today.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE OF BAZAAR

Stephen Mooallem is editor at large at Harper’s Bazaar. He is the former editor in chief of Interview and The Village Voice.