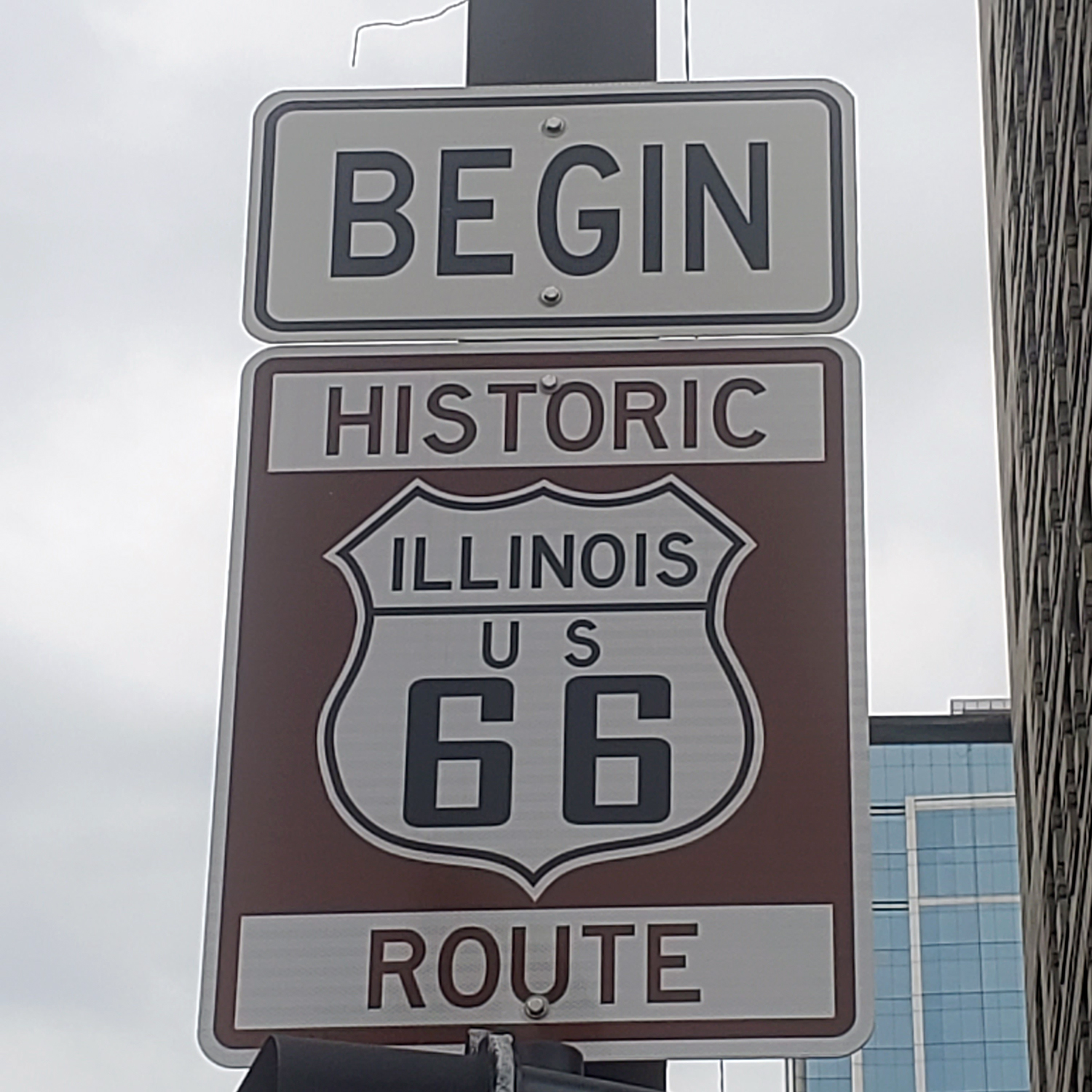

A journey of 2,448 miles begins with a single block. In the case of Route 66, that’s the 0 block of East Adams Street, at Michigan Avenue, where the “Begin Historic Route 66” shield faces the Art Institute of Chicago.

For a thoroughfare so associated with the Americana of an era before interstates homogenized cross-country travel, Route 66 doesn’t have a promising starting point. There’s a Walgreens on one corner, a Starbucks on the other. It does get more interesting, even here in Chicago. Although we’re mentioned in the song “Route 66,” Chicago doesn’t make as big a deal out of Route 66 as Pontiac, Illinois, or Kingman, Arizona, which both have Route 66 museums. We’ve got other tourist attractions.

Saturday was the 96th anniversary of Route 66’s designation as a highway, an event commemorated with this Google animation. We celebrated by traveling Chicago’s eight-mile-long stretch of Route 66 — even going beyond the city limits, to Cicero. There are still pieces of the American past to find there.

After passing two vintage restaurants — Miller’s Pub and the Berghoff — our first stop was the Marquette Building, at 140 S. Dearborn St., built in 1895. Step through the door labeled “Marquette,” under a bas-relief of the French priest-explorer wielding a calumet to repel an attack by Natives, and enter the most fabulous lobby in Chicago. The first floor is surrounded by an octagon of glittering mosaics depicting Marquette’s adventures, beginning with his first Native encounter and ending with his death on the shores of Lake Michigan, near modern-day Ludington. Above every elevator door is a bronze bust of an all-star from that early period of Great Lakes exploration: Tonty, Big Snake, Black Hawk, LaSalle, Waubonsie.

A few blocks further down Route 66 is the second-most fabulous lobby in Chicago, inside the Rookery Building, 209 S. LaSalle St. The Rookery was designed by Daniel Burnham and John Welborn Root in 1888, but its lobby was redesigned by Frank Lloyd Wright. Like everything else on which the master put his imprint, it bears signs of Wright’s Prairie style, especially the square light fixtures hanging from long chains.

“Wright removed much of the iron and terra cotta detailing on the central staircases, balconies, and walls, and replaced it with strong geometric patterns based on the railings of Root’s oriel stairs,” reads a building history. “He encased the iron columns in white marble that were gilded and incised with Root’s Arabic motif found on the LaSalle entrance. The fanciful electroliers that once flanked the central staircase were removed and Wright added bronze chandeliers with prismatic glass that still hang there today.”

In almost every town on Route 66, there’s a diner advertising its association with the Mother Road. Chicago has Lou Mitchell’s, 565 W. Jackson Blvd., — the only local institution that fully participates in Route 66 kitsch. When Route 66 opened in 1926, the three-year-old restaurant was on the highway, which ran along Jackson until 1955, when the boulevard became a one-way street headed east. Lou Mitchell’s is so devoted to its mid-20th Century image that it sports a half-burned-out neon sign advertising “the world’s finest COFFEE” — even though the restaurant closes at 2 p.m. The coffee, when sipped on a stool at the formica counter, is pretty smooth, but for a traveler, the real attraction is the small-townish pride in Route 66: clocks, a framed Life magazine cover, a t-shirt inviting diners to “Get Your Kicks at Lou’s,” and a Lou Mitchell’s Route 66 cookbook.

After traveling through the West Loop, past Old St. Patrick’s Church, Route 66 begins its southwesterly journey toward Santa Monica when it makes a left turn onto Ogden Avenue. The road passes the 1914 Beaux-Arts Cook County County Hospital, now a Hyatt House hotel, then cuts through Douglass Park. The park was originally named for Illinois Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, who brought the railroads to Chicago and debated Lincoln during the 1858 Senate race. Recently, however, an “s” was added, to instead honor abolitionist Frederick Douglass. However, chiseled into the facade of the 1928 fieldhouse, which contains an ornate ballroom, are the words DOVGLAS PARK RECREATION BVILDING. So they can’t take that away from the Little Giant. Douglass Park also recognizes its connection to Route 66, in a fading way. On a building south of Ogden is a flaking wooden mural depicting local roadside landmarks, from the Art Institute lions to the Skyline Motel, down the road in McCook.

Past Douglass Park, Ogden Avenue is a light industrial corridor of tire shops, car washes, liquor stores, storefront churches, and low-rise brick warehouses with banks of crossword puzzle windows and “For Rent” signs. The next landmark is the long-closed Castle Car Wash, 3801 W. Ogden Ave. A small stone building with a crenellated turret, it was built as a filling station in 1925, just in time to catch motorists on their way out of town. Supposedly it was also a hideout for Al Capone, although if Al Capone hid out in every place that makes that claim, there would have been six Al Capones.

That’s the end of Chicago’s Route 66, but it’s worth continuing on into Cicero. The Cindy Lyn Motel, 5029 W. Ogden Ave., was built in 1960 “to attract travelers headed into Chicago. We were originally known and marketed as the last motel before the city.” Decades after Interstate 55 replaced Route 66 as the fastest way to get to St. Louis, the Cindy Lyn is still there, and has even added hot tub suites. Henry’s Drive-In, 6031 Ogden Ave., is Cicero’s last remaining Route 66 diner. Opened in 1950, when hot dogs cost a quarter, it serves hot dogs, pepper and egg sandwiches, and now, bottles of Mother Road Route 66 Root Beer. Henry’s once had a competitor across the street: Bunyon’s, which was famous for its 20-foot-tall fiberglass Muffler Man, holding a hot dog. The Hot Dog Muffler Man was such a symbol of Route 66 that — after Bunyon’s closed — he was moved to Atlanta, Illinois, giving that bypassed village an attraction to lure travelers off I-55. If you ever wind the more than 2,000 miles from Chicago to L.A., instead of stopping just outside the city limits, you should pull over and see it.