Tasked with assessing the legacy of the relationship between James Stirling the architect and James Stirling the man, it’s fortunate that so much has been said of him by so many. By any measure his work was hugely influential. It was as complex and as unpredictable as the personality of this enigmatic man. What is the legacy of the work, and how was it related to the man who was lionised in his time? Were his few buildings isolated, unique creations of an exceptional individualistic talent (honed initially with James Gowan), which have since been stranded by the tide of history, or has he had a lasting influence? With the clear view afforded by time it seems that he left a legacy both immensely for good and in some respects for bad – a contradiction inherent in a larger-than-life figure who was sometimes an unreasonable man.

His architecture is the product of a complex, contrary and formidable man

After some 40 years in the wilderness, Stirling’s achievements are being reevaluated. The books, exhibitions and seminars bear testimony to his fascinatingly complex architecture, and many architects attest to his significant and lasting influence. Richard MacCormac said: ‘His DNA is somewhere in all architectural practice … he created a new kind of materiality and a new kind of sculptural space which belonged to the realm of art.’ MacCormac described his buildings as ‘harsh and bloody-minded, wonderfully spirited, and difficult for our coddled times.’ This architecture is groundbreaking but rooted in history, new but old, bold but carefully crafted – the product of a complex, contrary and formidable man. Ask some of his clients and they will say his buildings are those of an unreasonable man.

James Stirling

Also hanging on Stirling’s neck is a reputation for bad boy behaviour; the deliberate flouting of social niceties. The details are irrelevant but Stirling’s character was described by his friend and teacher Colin Rowe as ‘brash, gentle, generous, modest, immoderate, candid’, to which his biographer Mark Girouard added ‘subtle, prickly, abrupt, outrageous, naïf and childish’. But Stirling has also been described as extraordinarily generous, kind and humorous, and he was undoubtedly loved as well as revered by many worldwide. His friend Colin St John Wilson said in a wonderful memorial speech: ‘Did he really behave as badly as was rumoured? Yes, of course he did. His character contained almost violent contradictions and these were reflected in his architecture … He scorn[ed] playing safe and [had a] stubborn assertiveness to press a line of thought far beyond the limits of normal pursuit … Criticism wounded his pride but never made the slightest impression on his assessment of his own work.’

Advertisement

Stirling had an influence as great as Hawksmoor and Lutyens

Stirling strenuously promoted the art of architecture in his writing and his work, and had an influence perhaps as great as Hawksmoor and Lutyens. At the same time others say he has done the profession harm.

Axonometric of No1 Poultry by James Stirling

First the good: his legacy runs much deeper than the widespread imitations: the crystalline glass forms, use of red engineering bricks and vitrified tiles to wrap surfaces, the brightly coloured ship-like steel handrails, and the fluorescent socks. His legacy touches the core of architecture: the rooting of formal invention and expression in a building’s programme, the cubist-like elision of different forms and geometries, his distillation and expression of functional elements into exciting and dynamic compositions and – for me perhaps the most important – his ability to arrange 3D forms in breathtakingly dynamic arrangements held together by a simple and comprehensible armature of circulation. He elevated the Modernists’ creed of ‘form follows function’ (often untruthfully used) into the celebration and formal expression of a building’s function. He broke out of the straitjacket of a tired European Modernism that controlled post-war architects.

While having a deep understanding of architectural history, he valued every period but adopted no single credo. Instead his inventions and bravura revealed how architects can be free to adopt many approaches, whether formal Classicism, Gothic picturesque eclecticism or the celebration of construction’s nuts and bolts, which so influenced High-Tech designers such as Rogers and Foster, both of whom acknowledge his influence. He showed that architects could enjoy the play of making things, fiercely promoting freedom from stylistic and formal constraints.

This freedom is an aspect of his legacy that some reject, claiming the determination that the art of architecture comes above everything helped legitimise the role of the architect as a free spirit whose artistic aspiration counts above all else – an arrogance exemplified by Frank Lloyd Wright’s reputed comment to a client that if he didn’t want the roof to leak on him he should move his chair. The failure of many architects to meet clients’ practical expectations is reputed to be part of the negative side of Stirling’s legacy; a belief that the public should adjust rather than the architect or the architecture – an issue about architects’ duties and responsibilities that is very current.

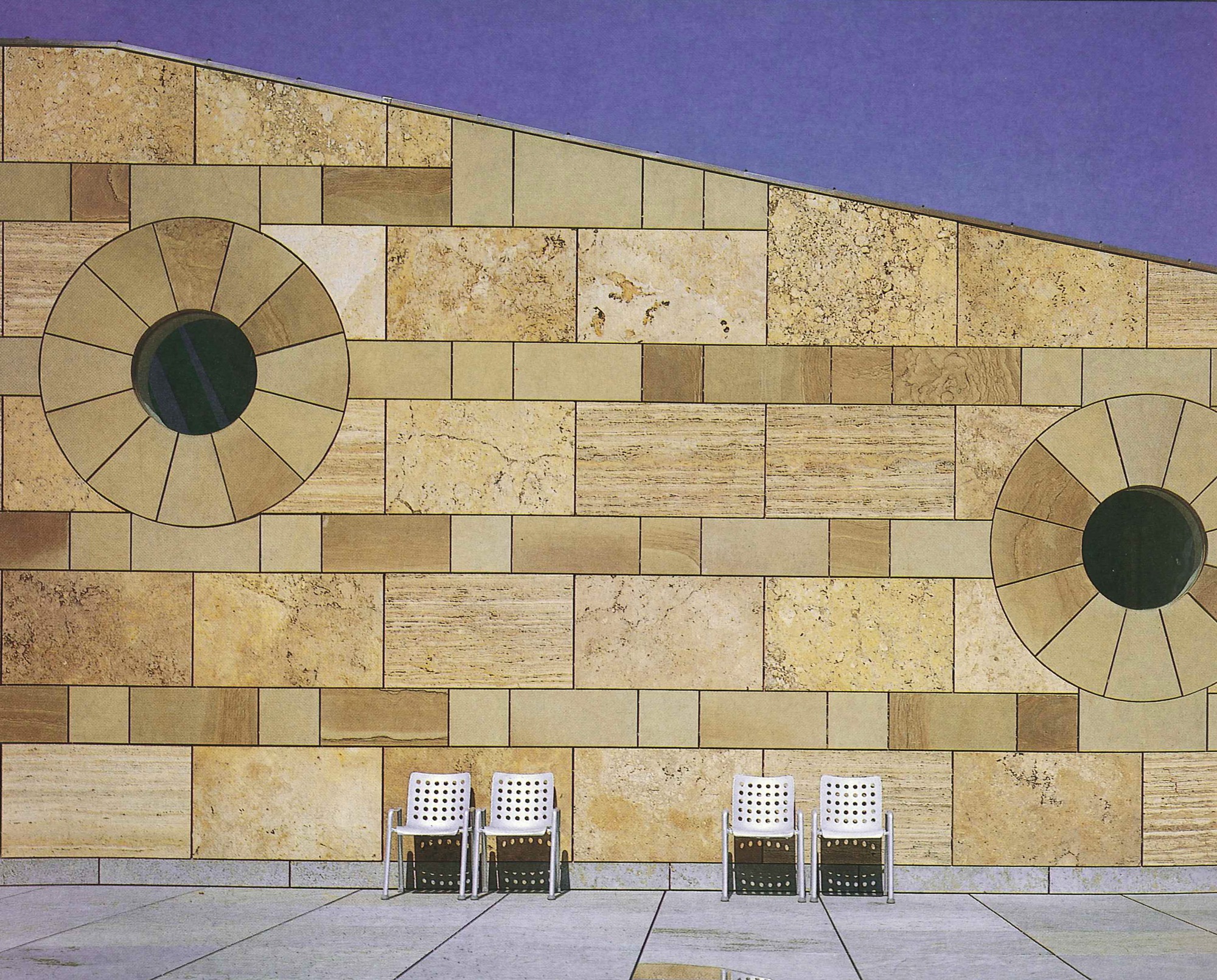

Another accusation against Stirling is that he conceived buildings as isolated objects with little contextual awareness. While he championed English vernacular traditions, he was interested more in their form than their context, and his hugely influential red buildings can indeed be criticised for appearing to land, like alien objects, on their urban sites with scant reference to their surroundings. But this approach was entirely overturned by his designs for the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart and other German projects that were deeply rooted in historic city fabric.

Advertisement

James Stirling’s Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

I do not claim it was Stirling’s fault that swathes of the profession are today obsessed with their own agendas and design stand-alone ‘look at me’ buildings, but it certainly can be considered part of the legacy of an architect who danced so prominently to his own tune. It was said at his memorial that Stirling showed that ‘the artist walks where the spirit blows him. He cannot be told his direction’ yet ‘leads the rest of us into fresh pastures, and he teaches us to love and enjoy what we often begin by rejecting.’

Stirling was evidently an extraordinary, complex and formidable man. In his determination to persuade people he was right, to push materials to their limit and contractors beyond their capability, in his unashamed use of historical precedent, his inventive creativity and refusal to accept the banal, and in his determination to do things his own way, he adhered to no rules and abided by no conventions, either architecturally and socially. He seems to have been an unreasonable man. But while reasonable men change themselves to suit the world, unreasonable men change the world. So thank God for unreasonable men.

Alan Berman remains consultant to Berman Guedes Stretton Architects and also works as Studio Berman. He edited Jim Stirling and the Red Trilogy: Three Radical Buildings and this year’s Stirling and Wilford American Buildings.

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

The Architects’ Journal Architecture News & Buildings

Leave a comment

or a new account to join the discussion.