In the early 1900s, not long after Ebenezer Howard realized his first Garden Cities, another designer put forward his own solution to the woes of urban life. French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, saw the machine age as a chance to remake society and improve the lives of all. Corbu’s ideas, which reached their ultimate form with the Radiant City, proposed nothing less than the complete destruction and replacement of cities with his concept of perfect, ordered environments.

To understand where Corbu’s ideals come from, it helps to explore his architectural philosophy. He was a leader in the modernist movement, and promoted functional, pure buildings. His philosophy is laid out in his “Five Points of a New Architecture:”

- Pilotis, or piles: Columns that support the a building’s mass, opening the ground underneath to free green space and allow for automobile movement.

- The free plan: The separation of load-bearing columns from internal walls, allowing free modification of the floor plan.

- The free façade: Similar to the free plan, the façade could be designed flexibly, since it had no structural function.

- The horizontal window: The free façade can be cut horizontally to light the whole space.

- The roof garden: Recover the sunlit green space lost beneath the building with a garden on the roof.

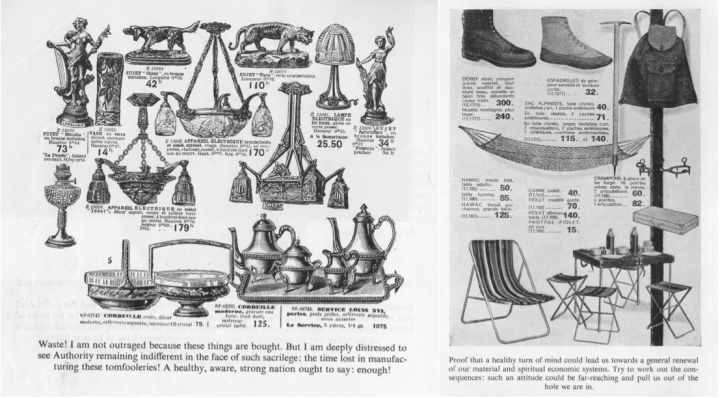

His functionalist ideology also appeared in an emphasis on raw geometry and opposition to decoration of any sort, separating the architecture from any preexisting culture. In his view, a building must serve as a machine, built to fulfill its purpose in the most economical way possible. He wanted to bring the industrial revolution to architecture, mass-producing buildings, and later cities, like cars or light bulbs.

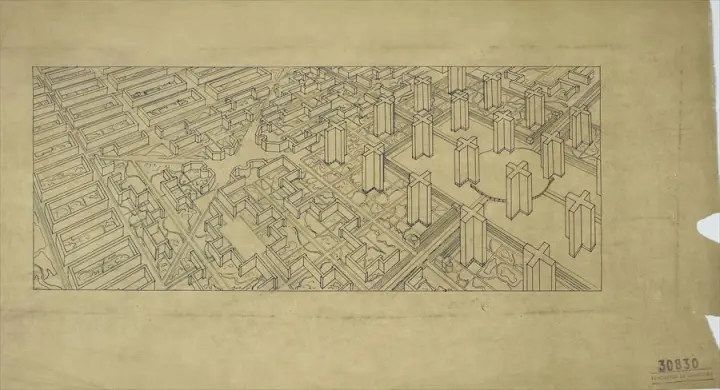

Le Corbusier’s first foray into urban planning was the Contemporary City (Ville Contemporaine), a universal concept for a city of 3 million. The plan was first presented at the Paris Salon d’Automne in 1922, and suggested a city of tomorrow based on “a theoretically water-tight formula to arrive at the fundamental principles of town planning” (Le Corbusier, 1929). This rational, uncompromising plan begins with an ideal site – level, open, and clear of buildings (which meant any attempt to build it would start with razing the previous city to the ground). From here, he plots a central business district of 24 identical glass skyscrapers on a 400-yard grid with broad park space between them. He thereby aims to increase density while decreasing congestion: 95 percent of this area would be open, and include various squares, restaurants and theaters.

Each skyscraper includes a tube station, part of a complex transportation system comprised of as many as half a dozen layers of distinct types of traffic, including highways raised above the ground and a central aerodrome for air taxis. Walt Disney would echo many of these ideas decades later.

Housing would be in similarly geometric low-rise buildings around this center, plus Garden Cities outside a protected ring of woods, fields and sporting grounds (reserved for expansion).

The Contemporary City was not as widely accepted as Le Corbusier would have liked, and in 1925 he determined it was time to push the concept with a more concrete focus: Paris. What he called the Plan Voisin would have radically redeveloped central Paris. Although today the area is one of the city’s most architecturally important neighborhoods, in the 1920s it was in poor shape, with sanitation issues and overcrowding.

Corbu proposed demolishing two square miles, preserving only a handful of the best architecture. He wanted to wipe out what he described as “a thousand different buildings … the beauty of ugliness … dingy and utterly discordant with one another,” condemning diversity in architecture. He recommended moving the current inhabitants (who he referred to as troglodytes) to new garden cities around Paris.

To replace the neighborhood, he would build 18 skyscrapers plus low-rise government, cultural, and residential buildings in a large, open space. The plan also included multilevel transit along the lines of the Contemporary City and three-tiered glass pedestrian malls overlooking the parks. Corbu promised that this plan would increase land values by five times, greatly benefiting both the state and any investors he gathered. However, support for the demolition of central Paris was, unsurprisingly, hard to find, if for no other reason than the cost.

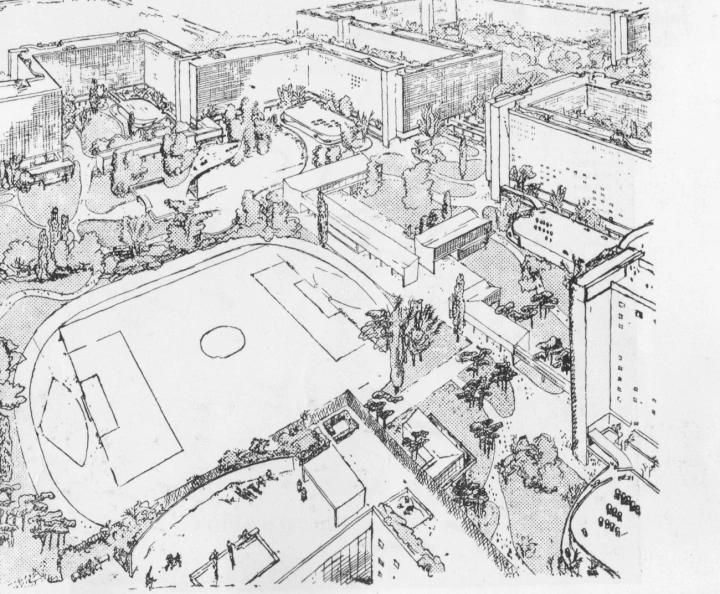

The culmination of Le Corbusier’s plans is The Radiant City (Ville Radieuse), published in 1933. The complex, universal plan went into more detail on every piece of the city than any previous plot, with a special focus on life in the city and residential spaces. It also went beyond urban areas to propose restructuring of rural land into “Radiant Farms” and “Radiant Villages.”

In The Radiant City, Corbu lays out the pieces of his doctrine, which he calls “definite principles and rules of conduct:

- “The Plan must rule.

- Disappearance of the street.

- Differentiation between simple and multiple speeds.

- What to do with LEISURE in the machine age; leisure could turn out to be the menace of modern times.

- The use of land in town and country.

- The dwelling unit considered as part of the public services.

- The green city.

- The civilization of the automobile replacing that of the railroad.

- Landscaping the countryside.

- The radiant city.

- The radiant countryside.

- The decline of money.

- The basic pleasures: satisfaction of psycho-physiological needs, collective participation and the freedom of the individual.

- The rebirth of the human body.”

–(Le Corbusier, 1964)

One of the themes he continues to discuss throughout is individual liberty, which Corbu narrowly defines as happiness and freedom from unpleasant tasks. He insists that constructing the city will give “work to everyone in it, which means we shall be able to banish, to forbid all sterile, self-strangling and stupid work.” He strives “to fill my modern man’s 24-hour day completely … make him a gift of personal liberty” (Le Corbusier, 1964). While he focuses on bringing sunlight, air, nature, and work to everyone, he also insists that almost anything outside his constricted view is wasteful or even dangerous. For example, when discussing women entering the workforce, he describes it as “female emancipation and freedom = ideal = illusion.”

The Radiant City is similarly puritanical. Employing geometric design and repetition, housing (a major difference between this and Corbu’s previous designs) is constrained at 14 square meters to a person. He compares the apartments directly to second-class train cabins, showing “the results of strictly observed economy.” The apartments are in long, geometric 14-story buildings, monotony he insists streets (again suspended in the air) on a differently spaced grid will disrupt.

Still, Le Corbusier’s radical ideas faced rejection from the broader field, and he became more and more bitter. Although he would design several master plans, neighborhood housing projects, and even the entire city of Chandigarh, India (I’ll write about these later this month), and his ideas continue to influence modern architects and planners, the Radiant City never achieved the universality he believed it would.

Ultimately, in trying to industrialize architecture and city building in the same way as the automobile, Le Corbusier failed to understand key elements of human nature. Mass-produced cars are acceptable because there is diversity between producers and models, so looking down a street you’re unlikely to see the same car twice. But a city built on his idealized forms lacks all the diversity that defines human existence.

Sources and Further Reading:

- Le Corbusier. (1929). The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning. New York: Payson & Clarke.

- Le Corbusier. (1964). The Radiant City; Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of our Machine-Age Civilization. New York: Orion Press.

- Fondation Le Corbusier. (n.d.). Fondation Le Corbusier. Retrieved May 26, 2019, from http://www.fondationlecorbusier.fr/

The danger with Corbu is only as long as you indulge in a cult of his personality. His actual work on the ground was always to the human scale, despite the grandiosity of his dreams that as a rule never went beyond his literary production, as he was a fantastic and provocative writer who depended on that talent for fortune and celebrity even more than on his actual designer’s work. He never pushed that hard for any initiative to tear down old Paris. He just submitted a plan of his own, for his own name and fame’s sake rather than any real hope of obtaining any job, to a fascistic tycoon (Voisin) who would did push for such a demolition to prevent future revolutions to brew again in those districts. He frequented all too many fascists but every architectural dreamer is bound to meet with authoritarian personalities. By the same time he did build a vaste expanse of factory workers’ duplexes around Bordeaux and everything was of convivial proportions, and all his other urbanism projects that would come thereafter insisted on keeping in place and restore every single bit of local architecture, including Arabic vernacular architecture in Algiers, that was above mere slums, at a time when French administration was busy destroying local character everywhere in regional and colonial France. Likewise he submitted various projects to Moscow, including a Soviets’ Palace, that never happened neither, which doesn’t mean he was a communist. When he met with fascism for real as France underwent German occupation and the Vichy regime, he and that ideological current parted for ever.

LikeLike

What an articulation of his pen & buttersheets!

LikeLike