Ask anyone who’s studied urban planning to explain the field’s history and one of the first names you’ll hear is Ebenezer Howard.

Howard was an English shorthand typist in the late 19thand early 20thcenturies. While working in Chicago, he saw the troubles of modern cities, such as rampant growth and housing shortages. He witnessed the struggle to resolve these issues in England after returning to London as a parliamentary reporter.

In his 1898 book, To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (reprinted in 1902 as Garden Cities of To-morrow), Howard laid out his solution: the garden city. Just five years after the book’s release, the first of these communities was founded: Letchworth Garden City, in Hertfordshire County, north of London.

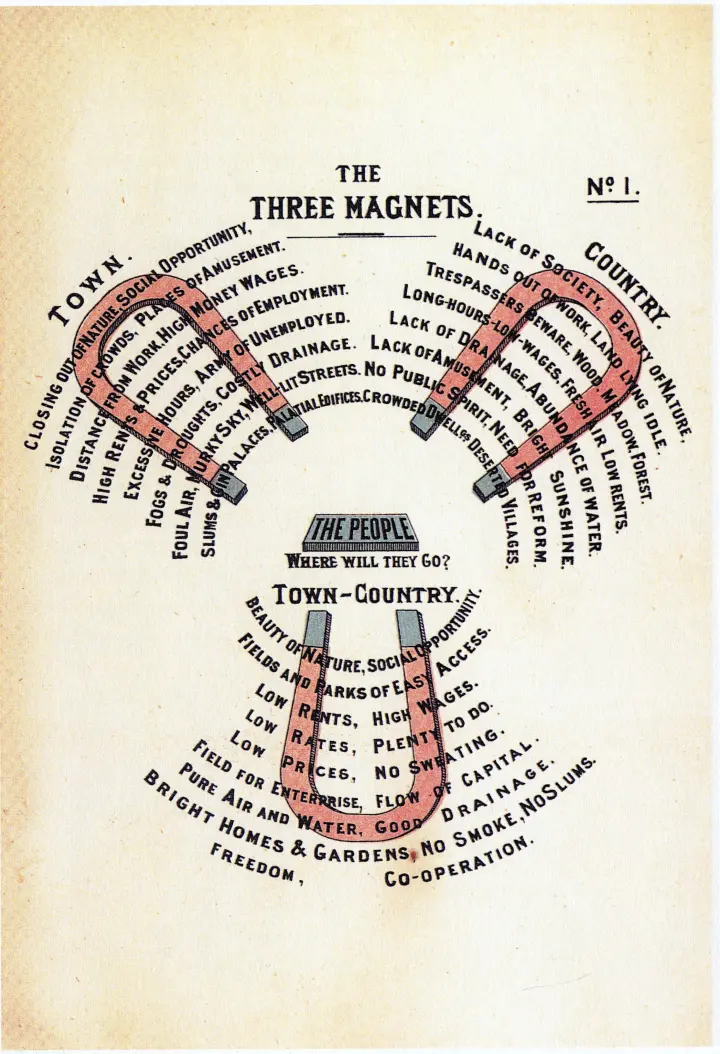

The principles of garden cities, as laid out in To-morrow, are detailed and thorough. Broadly speaking, the goal is to combine the appeals of town and country without the drawbacks of either.

A few key components make this possible. The city is surrounded by an inviolate greenbelt and large areas of land reserved for agriculture, preventing expansion of the urban area. The city is composed of rings centered on a park and “Crystal Palace,” home to a farmers’ market and winter garden. Working outward, six wedge-shaped wards hold residential and commercial properties, as well as the “Grand Avenue” filled with parks, schools, and churches. Factories at the outer edge send products off on a looped railroad. Railways could tie the town to other garden cities, each surrounded by a greenbelt and reserved agriculture space.

After the physical design, Howard explains how such a city could be run. A single organization holds all the land–a proposed 6,000 acres–in trust for the mortgage holders and residents. All rent and profits from city-run businesses are reinvested for the public good. The land value, supported by people coming to the town, is thus returned to the residents through infrastructure improvements and other public works. These values are maintained through a clear statement of intent in advance and a well-defined management structure, answerable to the people. This unique system of community ownership, self-sufficiency, and voluntary cooperation reflected anarchist and utopian thought of the time.

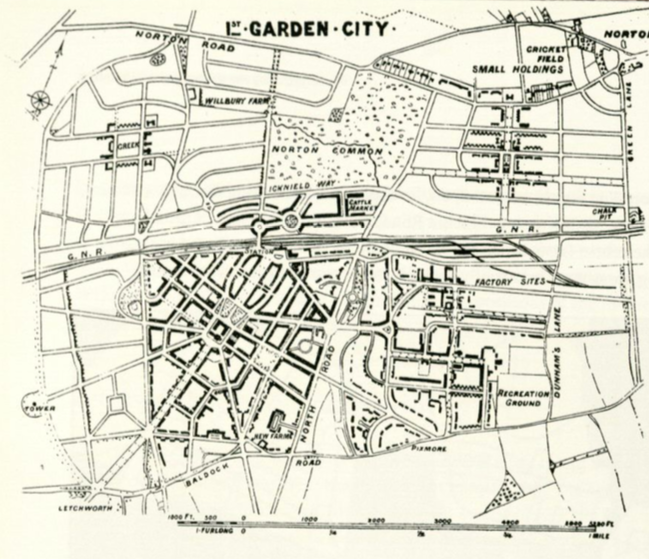

Letchworth Garden City was founded under the watchful eyes of Ebenezer Howard and his Garden City Association (GCA). The city faced certain limitations as it moved from ideal to practice. First, and perhaps most significant, the GCA leaders elected to found the city as a limited-dividend company rather than attempt to finance it through loans and granting the city title to a democratic council. This company promised five percent returns to shareholders, which meant it needed to ensure a consistent profit. Thus was First Garden City Ltd. (FGC) founded.

However, the company failed to raise full start-up funds, drawing only £40,000, half the desired amount. The city was unable to build houses and other facilities for more than 10 years, and the only middle-class families with the capital to build their own homes moved in. Without blue-collar workers or farmers, industry and agriculture struggled, as did FGC Ltd.’s profits, preventing the development of some of the democratic structures Howard envisioned.

Arts and Crafts architects Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin designed the city’s master plan–heavily modified from Howard’s outline to better fit the area. Compromises also had to be made for the sake of cost and comfort. Howard’s planning can, however, be seen in such beautiful areas as the central park and well-landscaped Broadway, as well as other preserved natural areas such as Norton Common. In fact, only one tree came down as the town was laid out.

Eventually, Letchworth developed a skilled manufacturing economy, featuring the Spirella Corset Company’s “factory of beauty,” a forward-thinking facility that focused on employees’ comfort. Growth in the agricultural sector was slow, but domestic gardens exploded: in 1953 there were an estimated 6,000 gardens in the city, each producing an average of 75 pounds of food. In 1946, Sir Frederic Osborn–who worked with Howard to promote later garden cities and headed the GCA after his retirement–described Letchworth as “a faithful fulfillment of Howard’s essential ideas,” noting the local employment, profit-sharing with the community, the demonstration of organic town planning, and the fusion of a single-owner leasehold with democratic ideals. Clearly, at this point, Letchworth was a success.

The community has had a massive impact, inspiring numerous follow-ups and imitators, including Welwyn Garden City–the only other built under Ebenezer Howard’s direct guidance–and Hampstead Garden Suburb. In fact, the International Garden Cities Institute–headquartered in Letchworth–lists garden cities on every continent except Antarctica. More broadly, the garden city movement influenced English New Towns (post-war government-planned communities), and is considered a cornerstone of modern urban (and suburban) planning. Ebenezer Howard also influenced Walt Disney’s EPCOT, and Letchworth has been linked to modern smart cities such as Masdar. The Garden City Association has evolved into the Town and Country Planning Association, which continues to work for healthy, affordable, and rational urban planning.

Letchworth Garden City itself is ultimately a compromise between ideals and reality. Today the Letchworth Heritage Foundation (First Garden City Ltd. was dissolved by statute after it was purchased and nearly destroyed in the early 1960s) operates the estate, still following Howard’s ideals of reinvestment and community health. In 1983, architect Mervyn Miller wondered if Letchworth’s limits on growth would cause it to stagnate and become “merely a landmark in the museum of planning.” Since then, however, it has only improved, drawing upon its history to become a leader in the ongoing development of garden cities. Now home to the International Garden Cities Exhibition and Institute, it stands at the center of efforts to bring Ebenezer Howard’s ideas into the modern era.

Further Reading

Garden Cities of To-morrow, Ebenezer Howard

English Garden Cities: An Introduction, Mervyn Miller

The Art of Building a Garden City, Kate Henderson

Miller, M. (1983). Letchworth Garden City Eighty Garden Years on. Built Environment (1978), 9(3/4), 167–184.

O’Sullivan, K. (2016). Letchworth: The first Garden City’s economic function transcribed from theory to Practice. Berkeley Planning Journal, 28(1), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/ina.12046

7 thoughts on “Ebenezer Howard and Letchworth: The First Garden City”