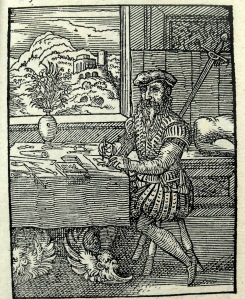

Detail showing a woodblock cutter (‘formschneider’) at work. Leaf C2r from Schopper’s 1574 ‘De Omnibus illiberalibus’, woodcuts by Jost Amman. Sp Coll S.M. 969

When you think back to your favourite childhood book, what springs most readily to mind: the text, or the illustrations? Well for me at least, the illustrations win out. Since I loved reading Roald Dahl books growing up perhaps this is not a surprise; Quentin Blake is, after all, an illustrator with a particular genius for capturing a character’s personality. But perhaps my preference for recalling image speaks to something deeper – the power of pictures to affect us profoundly and tell stories in a way which words cannot.

Detail from woodcut illustration from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472-1553), in Luther’s ‘Das newe Testament deutzsch’, 1522. Sp Coll K.T. f7

Drawing and writing have common roots in story-telling, and as ways of communicating ideas. While they have a relationship which doubtless stretches back into the mists of time, the value and utility of illustrations to complement and improve a text has certainly been understood during the age of print. From the mid-1400s onwards, printers have used different materials and adopted various techniques to create images which decorate and illustrate texts. Always interesting for one reason or another, at their best illustrations can be strikingly beautiful and can even lead to a whole new reading of a text.

This is the first in what will be a short series of blogs where I’ll look at different aspects of the history of printed book illustration. Today I’ll talk about the earliest method of printing illustrations in books, the woodcut.

The very earliest printed books had no printed illustrations at all – blank spaces for decoration were simply incorporated into the printed text allowing book buyers to commission illuminators and rubricators to add decoration by hand. However, it quickly became apparent that this approach had limitations; having a book decorated/illustrated required extra time and increased the overall cost, so as a result purchasers often left their books un-decorated. Printers saw in this an opportunity to make their books a more attractive proposition to buyers by adding printed illustrations – woodcuts were their solution.

Woodblock designer (‘reisser’) leaf C1r from Schopper’s 1574 ‘De Omnibus illiberalibus’, woodcuts by Jost Amman. Sp Coll S.M. 96

Woodblock cutter (‘formschneider’) leaf C2r from Schopper’s 1574 ‘De Omnibus illiberalibus’, woodcuts by Jost Amman. Sp Coll S.M. 969

Woodcut printing is a very simple idea, and one that predates the printed book. Essentially it involves using a chisel or gouge to cut a relief image into the plank side of a block of wood. The area to be printed is left standing proud while the negative space is carved away. Two people were usually involved in this process, the designer and the cutter. The designer would draw directly onto the block, or onto paper to be pasted to the block, before passing to the cutter to work on the block itself. Before the invention of the printing press woodcut printing was used to create things like playing cards, pilgrimage souvenirs and blockbooks (i.e. woodcut books produced without the aid of a press) but it was quickly co-opted by book printers who recognised in it a simple way of creating decoration and illustration that could be printed easily at the same time as the letterpress text.

Woodcut showing Poliphilo in a dark forest. Folio a3v from the ‘Hypnerotomachia Poliphili’. Sp Coll Hunterian Bh.2.14.

The earliest proper woodcut-illustrated books began to appear in Germany in the early 1460s; from there, woodcut illustration spread to Italy, the Netherlands, France and, by 1481, to England. Early efforts were usually fairly crude, often a simple outline print (so making it easier to hand-colour) but style and approach varied from country to country and even from town to town. By the end of the 15th century some beautiful and impressively balanced woodcut-illustrated books were being produced, none better than the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Woodcuts had clearly progressed from mere outline prints, intended for hand colouring, into a more sophisticated composition, with the inclusion of parallel lines striving after tone and contrast. These developments hint at how woodcut artists were looking to the tone, form and contrast achievable with intaglio copper engraving and attempting to replicate it in wood.

Some of the most interesting and intricate woodcut-illustrated books ever produced date to the period covering the last decade of the 15th century and the first 20 years of the 16th. One such example is the Teuerdank of 1517, an illustrated chivalric romance that relates the many adventures of Emperor Maximilian I on his journey to meet his bride. Containing 118 cuts in all, it is a superb example of the work being produced in Germany at the time, one of the finest periods for German book illustration. The shift in book illustration from crudely executed cuts to true works of art is usually attributed to the influence of Albrecht Dürer, who carried the art form to new heights in works such as the Apocalypse and the Life of the Virgin. The illustrations in the Teuerdank were produced by a team of artists: Leonard Beck, Dürer’s pupil Hans Schaüfelein, and Hans Burgkmair – a reputable Augsburg artist who was also involved in Maximilian’s Genealogie. The drawings they produced were then cut by Jost Dienecker of Antwerp.

As the 16th century progressed woodcut illustrations gradually began to lose ground to copper-engraved illustrations. Woodcutters fought a losing battle attempting finer and finer cuts, trying to emulate what was achievable in engraving. However by around 1600 intaglio engraved book illustrations had largely replaced woodcuts, and while relief-printed illustrations from wooden blocks resurfaced again at the end of the 18th century – with a different name (wood engraving) and using a slightly different technique (more on this in a later blog) – the ‘golden age’ of the woodcut was over.

Categories: Special Collections

Johnny Beattie: ‘The Clown Prince of Scotland’

Johnny Beattie: ‘The Clown Prince of Scotland’  The Arte of Faire Writing

The Arte of Faire Writing  Visualizing Collation in the Hunterian Manuscript Collection

Visualizing Collation in the Hunterian Manuscript Collection  Sugar Machines: How Archives in Glasgow hold pieces of Caribbean History

Sugar Machines: How Archives in Glasgow hold pieces of Caribbean History

Leave a comment