Richard Wentworth OBE is primarily known as a one of the most influential British sculptors of his generation who for forty years he has used a camera as a way of making “casual notes …. of situations which attracted me” (1). He does not see himself as a photographer and his photographs speak to his self declared casual note taking, there is no particular evidence of technical skill or formal composition which Anna Dezeuze argues references his work to the conceptual photographers of the sixties and seventies such as Ed Ruscha and Sol Le Witt.

Alternatively, if we view Making Do and Getting By (2) in isolation, given the book is limited to his digital collection as captured between 2006 and 2015, his work could be aligned with contemporary trends in vernacular photography; an Instagram Account in print. His images are executed quickly and simply, framed and composed casually often disregarding depth of field or lighting conditions. But there are two elements that undermine any suggestion of external influence or references.

Firstly, whilst the photographs neither reference nor act as references to his sculptures there is an obvious alignment of philosophy and output in the two mediums. Secondly, his choice of subject is not only a very personal perspective of urban life but has been consistently and deeply explored for four decades. We can be tempted into over analysing his photographic work and align it with various movements in contemporary photography but in reality the only relevant reference is the artist himself. This in itself makes this series unusual, it has been created outside of and in parallel with the mainstream of photography history, uninfluenced and seemingly unaware that the mainstream exists; in the interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist that introduces the book (2), he discuses sculptors, architects and writers; photographers are notable by their absence.

This is a generous book, 750 photographs of found street sculptures, presented in sets that suggest a series of journeys, urban walks but that often jump between cities. Wentworth himself suggests that the viewer shouldn’t “dwell on a page”, it is best absorbed at the pace of a walk, steadily turning the pages, going back and forward as we make connections and begin to see the categories that many of the pictures fit into.

Given the volume of pictures the range of subject matter is unsurprisingly huge but the majority fit very neatly under his Making Do and Getting By title, Wentworth is intrigued by the “very high material intelligence” (1: p294) of people, a natural practicality and ingenuity that he believes is disappearing as we move further from our agrarian roots. Kevin Henry describes a discussion with Wentworth about the tendency for a farmer to close a field gate with string rather than using something that has come through an industrial process (3), anyone who has spent any time around farms knows that binder twine is the universal material of repair; in more industrialised or urbanised environments its role has been usurped by cable ties and gaffer tape. On the farm, in the workshop or on the street people revel in solving problems and fixing things by usurping the materials on hand, modifying or reconstructing them to suit new purposes; an act that Paul Carey-Kent calls “non-conformist inventiveness” (4) and Wentworth both investigates and celebrates these little acts of intervention.

“I grew up in a world that was held together with string and brown paper and ceiling wax and that’s how it was and I probably fantasised that I needn’t be like that but then I slowly realised (it) actually is somehow the underlying condition of the world.” (3: p18)

Some of these appropriations and repairs are casual, an item on-hand put to a new use, but often and quite intriguingly there are often signs of care and craftsmanship, a desire to make a “proper job” of it.

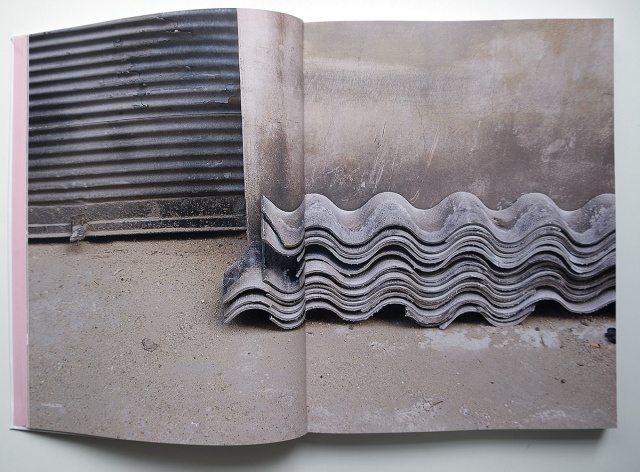

There are other deeper levels to this series; as a sculptor, Wentworth is sensitive to the juxtaposition of materials so many of the photographs explore chance meetings of textures and contrasting forms. In Istanbul 2006 there are several of these contrasts, the rough texture of asbestos sheeting against the smooth concrete and finished steel, wavy versus linear, soft versus hard, sophisticated industrial techniques versus a simple manufacturing process, temporary against permanent, the lines incorporated and fixed into the production process of the door against the repetitive lines created by the human intervention of stacking the sheets . Wentworth sees these relationships as “little circumstantial geometries or comedies” (2: p.8)

Wentworth proves himself to be an accomplished analyst of his own work; the interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist includes a walk-through of a small number of the images. Wentworth sees complex relationships between objects that few others would notice. He describes the thinking behind the photograph of a tomato in front of a car tyre as:

“It’s the fact that the tomato is like a cartoon – we know that it is fundamentally a squishy thing. The tyre is also a vegetable product, substantially still connected to trees and oil, and the tomato has been fertilised, probably with oil products, and is a vegetable (or technically a fruit)” (2: p.14)

In essence it is the serendipitous nature of relationships between objects and of Wentworth noticing and photographing them that makes the series so compelling. The straight yellow no parking lines in parallel with the pavement creating visual tension with the half round table tops lent against the vertical black railings of an urban fence; the perfect asterisk formed by tyre tracks on a snowy street; or a bicycle saddle left at the exact centre of formica cafe chair. It is, as Wentworth suggests, “full of humans” (2: p.10), but without a single human subject. We are left considering which of these street sculptures are intentional and which are part of the random nature of people’s interaction with their environment but beyond that each of these structures documents a little human act, the making, fixing or modification of the environment and in that sense as a series is as much a historical document as Atget’s scenes of old Paris.

The book includes a glossary, a list of words that particularly appeal to Wentworth and that describe the “ingredients of the book” (2: p.9): the fact the glossary runs to over 250 words provides a sense of the breadth of his subject matter and provides a clue to the way his mind works. Wentworth is interested in language and how words have been forged and then used, he not only enjoys the subtleties of our language but how those words describe the found situations he photographs. I would argue that Wentworth, if not unique, is certainly unusual in that his photographs and the way in which they are presented combines photography, documentary, language, architecture, sculpture, social and cultural anthropology and archaeology. At a superficial level each image raises questions about how the situation came to pass but the context of this series also suggests we are conscious of found sculpture, of patterns of behaviour that describe aspects of common traits and individual personalities.

An interesting question would be whether this series is conceptual art? Undoubtably the ideas behind the work take precedence over any traditional notion of aesthetics but Wentworth often identifies pleasing patterns created by light and instinctively recognises strong colour combinations and compositional forms. And whilst it is not sophisticated or accomplished at a technical level there is no sense that Wentworth is actively building a vernacular snap-shot aesthetic into his work, the photographs just happen to be that way. In some ways it is a companion book to John Pawson’s A Visual Inventory (5); Pawson, an architect, has collected over a quarter of million images that record landscapes, buildings and architectural details that inspire or just intrigue him. Like Wentworth he uses the camera as a note book, a visual diary, and whilst he is more often investigating form and the juxtaposition of colours and patterns his work is similar to Wentworth’s in that it reveals the thought processes of an accomplished practitioner in an art medium parallel to photography.

Sources

Books

(2) Wentworth, Richard (2015) Making Do and Getting By. London: Koenig

(5) Pawson, John (2012) A Visual Inventory. London: Phaidon.

Internet

(1) Dezeuze, Anna (2013) Photography Ways of Living and Richard Wentworth’s Making Do, Getting By (accessed at Acedemia 30.9.16) – https://www.academia.edu/5269475/Photography_Ways_of_Living_and_Richard_Wentworths_Making_Do_Getting_By_Oxford_Art_Journal_36.2_2013_pp._281-300

(3) Henry, Kevin (2007) Parallel Universes: making Do and Getting BY plus Thoughtless Acts (mapping the quotidian from two perspectives) (accessed at Acedemia 30.9.16) – https://www.academia.edu/4353804/Parallel_Universes_Making_Do_and_Getting_By_Thoughtless_Acts_mapping_the_quotidian_from_two_perspectives_

(4) Carey-Kent, Paul (2011) Interview with Richard Wentworth (accessed at The White Review 30.9.16) – http://www.thewhitereview.org/interviews/interview-with-richard-wentworth/