Dogville: a Youdontsay Movie Review

Dogville is a highly-regarded 2003 drama film, written and directed by Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier, who was previously notable for founding the Dogme 95 style of avant-garde filmmaking. The Dogme 95 style sets up certain purist rules that a director must follow when making a film, such as shooting on location, using authentic sound, and not taking credit for the work. The movement was a reaction to Hollywood films which von Trier felt were becoming inauthentic due to their heavy use of CGI and editing. The narrative of Dogville is told as if it is the theatrical presentation of a written story. The narrator reads this story aloud as we witness it unfold, and the film is divided into nine “chapters,” complete with explanatory headings. The somewhat cliché voice of the narrator is intended to subtly parody the narrator of “Our Town,” which was a fairly sappy and optimistic play about a small American town. In Dogville, von Trier decided to break all of his Dogme 95 rules, presumably in order to emphasize the doubly-fictional quality of the film's story-book narrative.

Dogville concerns itself primarily with two characters, Thomas Edison and Grace. (If the name Thomas Edison doesn't already seem like an obvious enough allusion to American history, the first diegetic sound heard in the film is a radio in Tom's room which says, “Ladies and Gentlemen, the president of the United States of America...”) Tom, a writer, invites Grace to stay in Dogville after assisting her in hiding from a car full of gangsters. In exchange for the shelter, Grace performs menial tasks for the residents. Once the police start looking for her, however, Grace's rent goes up. Her duties increase, her wages vanish, and the men of the town start raping her left and right. Tom, who initially seemed sympathetic to Grace's distress, proves himself to be as slimy as all the other men in town, if not slimier. Ultimately, the gangsters arrive, and Grace instructs them to slaughter the citizens of Dogville. In her opinion, none of the residents were worthy of forgiveness.

Reviews of the film were extremely polarizing, mostly due to it's overtly anti-american message and bleak moral picture. While there were many critics who hailed the film as a masterpiece, a quick Google search reveals that most American critics are primarily concerned with proving the opposite. In fact, one can find many an article lamenting that the film has been hailed as a masterpiece, but very few articles actually describing it as such. Take, for example, Charles Taylor's article for Salon magazine. The tag-line reads: Lars von Trier's Depression-era fable has been labeled "anti-American," but it's even worse: It's anti-human.5

In a truly scathing review, Taylor writes:

In every respect other than sheer length — in scope, imagination, execution, depth and spirit — Dogville is a piddling movie. That hasn’t stopped it from being widely acclaimed as a masterpiece. Are the critics who are rhapsodizing over Dogville actually swallowing its puny, rancid view of humanity or are they afraid that slamming it means they’d be showing themselves not tough enough to take its hard truths? Reading the raves for Dogville, I’ve thought of the girl in Michael Ritchie’s “Semi-Tough” who announces at an encounter group, “I peed in my pants and it felt good.” Except that to get any pleasure out of Dogville you’d have to say, “I was peed on and it felt good.”

While Charles Taylor takes his example to a humorous extreme, it is not without vindication. As an American watching this film, it is tough not to feel offended by the depiction of everyday Americans. Evidently, Taylor was a bit more offended than most. He goes on to write of Dogville:

Shot by Anthony Dod Mantle in watery, grainy color, the endless close-ups waver drunkenly on the screen. The movie is just as washed-out and ugly looking as “Breaking the Waves” and “Dancer in the Dark” were. (To talk about the aesthetic qualities of a von Trier movie is a joke.)

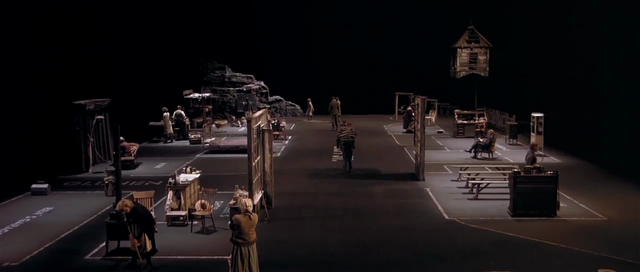

Taylor quickly loses my endorsement with this series of statements. The aesthetic qualities of the film may not have appealed to everyone, but they are certainly no joke. In fact, the aesthetic quality of Dogville is one of the only things keeping it alive and interesting. The spare, theatrical set allows us to see into the lives of the characters and it pertains directly to the literary themes at work. We can imagine the town as a little map that Tom has drawn inside the cover of his book, perhaps.

In this excerpt, Charles Taylor reveals that he, like many critics, has trouble seeing past the troubling moral implications of the film. His anger with von Trier over the message seems to cloud his judgement regarding the delightful and arresting manner in which the film is shot. However, Taylor does have a good point when he compares watching the film to being peed on. Certainly, as an American, it is hard not to be offended and disturbed by the film when America seems to be singled out as the target. Are we right to be offended? Are we right to assume that this film can be reduced, simply, to an anti-American message? And, if so, how should an American viewer interpret this message?

The depravity of the residents of Dogville cannot be attributed to American Capitalism, American democracy, or any other specifically American theme, with the exception of (perhaps) the Great Depression. The residents have very little money and meager quantities of food, but their manipulation of Grace rarely has anything to do with nutrition or survival. For the most part, she is either raped or used for menial chores. Without demonstrating a malevolent American system that imposes these lapses in morality upon the citizens of Dogville, von Trier seems to be saying that American citizens are just evil in general, independent of their circumstances. While this may not have been von Trier's intention, it is certainly the effect of his film. Thus, Roger Ebert is correct when he writes, “His dislike of the United States (which he has never visited, since he is afraid of airplanes) is so palpable that it flies beyond criticism into the realm of derangement... Von Trier could justifiably make a fantasy about America, even an anti-American fantasy, and produce a good film, but here he approaches the ideological subtlety of a raving prophet on a street corner.”

The problem, for Ebert as well as many other critics, is that the story is explicitly about the moral climate America, but it does absolutely nothing to identify the source of the depravity it depicts. By the end of the film, we are unsure whether von Trier is condemning Americans or all of humanity. Our confusion is immediately alleviated, however, as soon as the final credits begin to roll. Alongside black and white images of poverty in the United States, we hear the David Bowie tune “Young Americans.” While the full meaning behind von Trier's message is unclear, the superficial message of the credits is simple and obvious: This was a film about the United States of America.

In regards to the American allusions in the credits, Christopher Orr writes:

These touches are not, as many of Dogville's defenders argue, mere provocations, incidental to a deeper message about the universal human capacity for evil. Indeed, von Trier explicitly rejects that interpretation late in the film when Bettany announces he intends to write a book, perhaps even a trilogy, about the cruelty of a town just like Dogville. "Why not just call it Dogville?" Kidman asks. "No, no," he replies. "It has to be universal." Unlike Bettany, von Trier does not share this concern.

Orr's argument is mirrored by Ed Hernandez in his review of Dogville for Slant Magazine. In what is surely a testament to the subjectivity of the medium, Hernandez used the exact same examples as Orr but reached the exact opposite conclusion. According to Hernandez:

Though Grace's final conquest can be read as a campaign for cultural euthanasia, the film's devastating final credits—which juxtapose David Bowie's "Young American" with photojournalistic memories of American underdevelopment—are unmistakably sympathetic. Von Trier understands that the root of American aggression may very well be our arrogant elite's oppression of the culturally underprivileged, which has bred ignorant and isolationist attitudes throughout the ages. Contempt breeds more contempt, so to speak. "It's got to be universal," says a confused Tom at one point, widening the director's political perspective. In the end, Dogville is less anti-American than it is, quite simply, anti-oppression.2

The meaning behind Tom's “It's got to be universal” line is clearly up for debate. It suggests that von Trier is at least aware that good stories need to be universally applicable. Orr makes a good point, though. If Tom needs a more universal title than “Dogville,” why does von Trier settle on this very name? Perhaps Orr and myself are reading too far into things, but it seems as if von Trier is trying to say, “Don't worry, European viewers. This isn't about you. Only the residents of Dogville (i.e. Americans) are this bad.”

When asked by Marit Kapla why he chose to make another film set in the U.S., von Trier replied that he was provoked by journalists who were angry about his first film about America, Dancer in the Dark.3 He goes on to say, “I also thought that it might be interesting for the Americans, and for others, to find out how someone who's never been there sees America. If it were my country, Denmark, I would like to know what someone who hadn't been there thought. Perhaps they'd only think of the Little Mermaid, or that polar bears roam around there. How should I know? In any case, it's interesting to have one's country illuminated. I didn't think it was such a great sin. Besides, that is just what American filmmakers have always done.”

Apparently we can now close the book on our hypothetical debate between Hernandez and Orr. Thus stated from the director himself, Dogville expresses opinions specifically about America, and not just about the universal human condition. Quite clearly, Christopher Orr comes closest to the truth. While Herndandez may be correct in asserting that the images of poverty in the closing credits are “sympathetic,” there are countless scathing reviews of the film which would seem to contradict the “unmistakably” aspect. Von Trier may indeed believe that American contempt and depravity arises because of oppression from the elite, but there is no evidence to suggest this within the aforementioned photos or any of the rest of the film. The entire story takes place in the rural setting of Dogville, and the despicable town-folk are the only representation of America that we have. The gangsters are the closest thing we see to malevolent elitists at any point, and, with the exception of the police officer, government figures are completely absent from the story.

Von Trier says it is “interesting” to have one's country illuminated. While it is no doubt interesting, some might find it hard to accept that the United States has actually been illuminated by this film. It's difficult to imagine that a theatrically staged period-piece (directed by a man who has never set foot in the United States) could shed too much light on modern day America. Von Trier compares his work to a hypothetical American filmmaker dispensing with misconceptions about Denmark, and informing the public that there is more to the nation than Polar bears and The Little Mermaid. In the end, however, the only cultural misconception that von Trier seems to be concerned with is the one that claims American citizens might possess a modicum of morality. In response to von Trier's assertion that “this is just what American filmmakers have always done,” Kapla rightly inquires, “You mean they've portrayed countries they've never visited?” To which, von Trier replied, “Yes, always. Of course, they never went to Casablanca. That's why I find it difficult to understand why we may not reciprocate.”

It is common knowledge that American filmmakers occasionally set their stories in countries about which they have very little knowledge. The difference, here, is that von Trier is not merely setting a story in America, he is crafting a scathing critique about America. The example of Casablanca works perfectly to illustrate this disparity. While Casablanca takes place in a fictionalized version of Casablanca, the lack of first-hand knowledge on part of the filmmakers is made irrelevant by the fact that the film's message is largely universal, and the commentary on the nature of Casablanca and its inhabitants is subtle and completely tangential to the narrative. It is a story about human beings that just-so-happen to be in Casablanca. The setting is a back-drop and plot-device, but there is no anti-Moroccan political undertoe. Von Trier's characters are not afforded the same individual identities as Rick, Ilsa, and the other players in Casablanca. They are all treated solely as Americans, and thus they are shackled to this (apparently negative) thematic identity. In comparing the making of Dogville to the making of Casablanca, von Trier misses the point of his detractors entirely. Whether or not Morocco is accurately portrayed in the film Casablanca is entirely irrelevant, as the film contains no overt message about Morocco or its people. The setting provides a means for presenting the subject matter of the film; it is not the subject matter itself. Having never visited the nation he attempts to lambast, von Trier becomes like a young child refusing to try a new kind of food-- peanut butter, say. Rather than explore the pros and cons or give the food a chance, von Trier is content to say, essentially, “I hate it, I hate it, I hate it!” without any experiential basis. His defense of this effort is weak at best.

Von Trier goes on to say, “...The Depression was a good setting for this story. Also, my experience has been that if you choose a time other than the present, the film becomes more realistic. In some way it becomes more like a documentary and assumes greater authority.”3 Perhaps I am beginning to pick at nits, so to speak, but once again von Trier has made a statement worthy of scrutiny. First of all, coupled with his “illumination” quote, this statement suggests that von Trier considers his knowledge of America to be, perhaps, more accurate and more complete than that of an actual American. While his statement pertains to filmmaking in general, the “documentary” reference implies a strong confidence in the validity of the film's portrait of America. However, the aesthetic and the questionable attempt at vernacular brings that validity into question.

In Christian Orr's article for The Atlantic, he notes that Lars von Trier's previous two films, Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark, shared similar narratives with Dogville, but were more neutral in their balance of love and hatred. In all three films, a leading-lady is subjected to cruelty and abuse. Dogville is made distinct by the extreme bleakness of its moral landscape, and by the leading-lady's eventual decision to stop turning the other cheek and exact revenge on her tormentors. Grace's ultimate decision to cleanse the Earth of Dogville can be taken one of two ways. A: Grace is still good at heart, and she is doing the world a service by ridding it of Dogville (our symbolic version of the evil U.S.A.). Or B: Grace has inevitably turned evil, and has now become no better than all of the other cruel Americans.

In either case, the anti-American message is clear, and the American viewer is subsequently left with a feeling of guilt and discomfort. Unfortunately, the film does not provide us with a means of coping with the fear and anxiety it imparts upon us. Our only cathartic release is the execution of the Americans we have grown to hate over the course of the film. We are not shown a more ideal model of morality, we are simply informed that ours is wrong and that we are necessarily evil because of it. In the words of Christopher Orr:

Von Trier's entry is so vicious in tone, so exaggerated in metaphor, that it's all but impossible to take it seriously. Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark mapped similarly bleak terrain, but both still contained music and sunlight, kindness and love, hope and forgiveness. One might have imagined that Dogville, a film more political than existential and one aimed at a more particular target, would have taken still greater pains to establish the presence of good amidst evil... In the Dogme 95 manifesto that he coauthored, von Trier decried the current film scene as "an illusion of pathos and an illusion of love." With Dogville, von Trier manages only half that.

In the end, it is undeniable that Lars von Trier has crafted a sleek, clever, and original work of art. However, Dogville falls short of being dubbed an instant classic because of its underlying message. Either humanity is evil or Americans are, but what difference does it make? How, as an American, do I benefit from being informed that I'm essentially a depraved sociopath, destined to make selfish choices for the rest of my life? Perhaps that is not the intended message, but without a single morally-vindicated character in the film, one cannot say that it is not the message. Von Trier has undoubtedly crafted an interesting and worthwhile film, but the value comes entirely from its delivery, and not from the anti-American message being delivered.

Cover Photo: Image Source

I watched it but I really don't remember much only that it was a weird movie or at least was what I though at the time. Now I want to watch it again.

good review @youdontsay is very complete

It's a very interesting movie, but I never finish it with this review and I want to finish seeing it

Una pelicula del año 2003, no habia escuchado de ella pero ya que despierta tantos sentimientos encontrados provoca verla y dar mi opinión acerca de ella @youdontsay

Great article!

Please do not hesitate to view some of my recent posts.

To listen to the audio version of this article click on the play image.

Brought to you by @tts. If you find it useful please consider upvoting this reply.