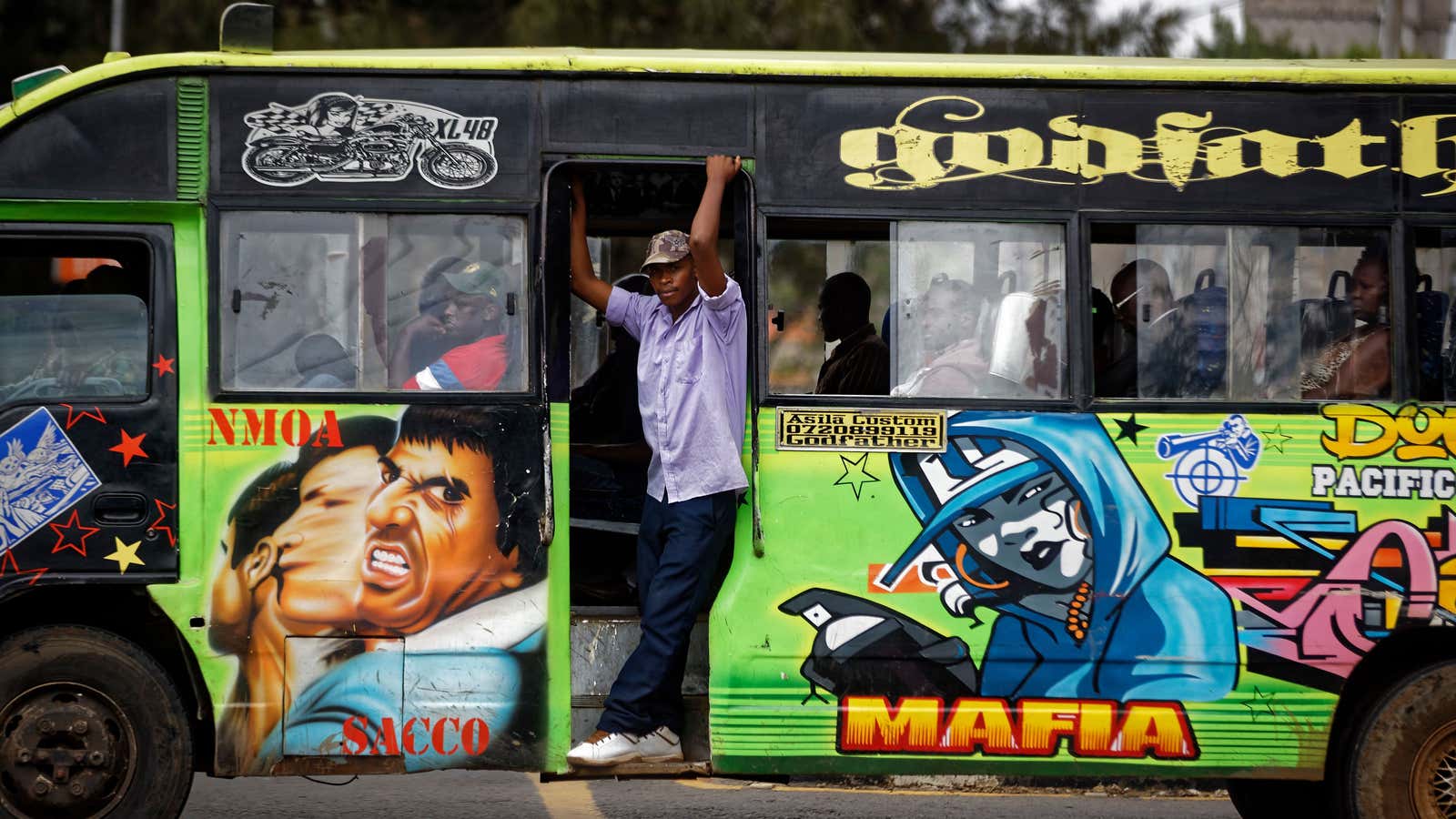

Kenya’s ad-hoc matatu bus system has been described as cool and colorful but it is also very chaotic. For years now, transport officials have tried to rein in the sector in a bid to decongest major urban areas and introduce rapid bus transits that would improve capacity and reliability. But those efforts have so far proved vain, and with little or no light railway, trams, or cycling lanes, millions of commuters in cities like Nairobi and Mombasa use the unruly and loud matatus to move around daily.

Now, a slew of app-based, hailing services wants to disrupt public transit in Kenya by testing ways to get customers to destinations with fewer stops, at affordable prices, while maintaining high quality and safety standards.

In the last two weeks, Little, the ride-hailing app backed by Kenya’s largest mobile operator, Safaricom, and Swvl, the Cairo-headquartered bus transportation service, have begun piloting bus shuttles in Nairobi. Their busses have been plying routes in the city and testing which neighborhoods have more demand and how passengers react to a pre-booked service.

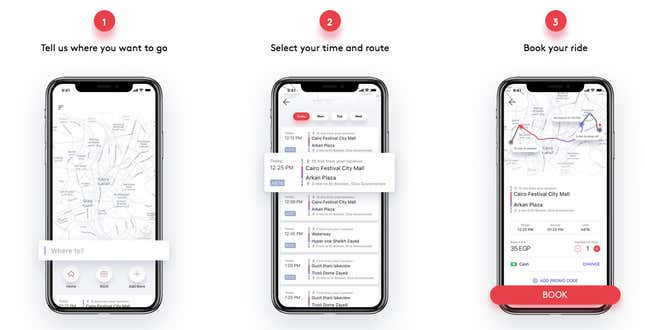

Each company says it wants to improve the transport ecosystem in Kenya by signing “high quality” matatus onto their platform, thus creating more opportunities for drivers instead of competing with them. Customers will be notified of arrival time, picked at specific stops, provided with wifi in the case of Little, and will be able to pay in advance, use mobile money or pay cash before drop-off.

Heeding previous government proposals to phase out 14-seater matatus, which has faced growing protest from matatu owners, Little and Swvl are using 23- and 26-seater buses in their public pilots respectively and hope to fully launch by late January or early February.

“There’s a lot of chaos in this space,” says Little’s head Kamal Budhabhatti. But in looking for ways to sign more riders “we thought there’s an opportunity for us to get into the bus space and gain some experience.”

After raising $30 million in Series B funding last year, Swvl founder Mostafa Kandil says they scouted markets in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Pakistan for expansion plans beyond the over 600 lines they currently run in Cairo and Alexandria. They chose Nairobi, he says, given the availability of “tech-savvy” consumers with access to internet and mobile money services, who were willing to experiment with how they move from one point to another.

Disrupting substandard public transport options in Africa, and especially in growing urban areas with notoriously heavy traffic, has come to the fore in recent years. The move also signifies efforts by e-hailing services to tap into other cheaper, locally-popular forms of motorized transport including rickshaws and motorcycles.

Last month, Uber launched its first bus service globally in Egypt. (The tech giant previously expressed interest in the Kenyan market but now says it isn’t “launching in Kenya, or across Sub-Saharan Africa at this time.”) Its Dubai-based competitor Careem also launched a bus service in Egypt, while Kenya’s Safiri Express is currently piloting a bus shuttle that mostly avoids the central business district. Both Tanzania and Rwanda have also experimented with smart transportation options to ensure convenience and end long passenger queues at bus stops.

Yet, rolling out a bus service in Nairobi will likely be easier said than done. Matatu buses and routes are privately owned and operated by touts and drivers, who don’t own their vehicles, usually apply aggressive measures—doubling prices when it rains, driving fast to complete more trips—to make a profit. Operators have also resisted previous efforts to digitize and take cash out of their hands.

Matatu owners are also all part of what’s known as savings and credit cooperative organizations or SACCOs who lobby hard against government directives and have opposed previous efforts at reforming public transportation. With time, shuttle services could also face the same problems that have dogged ride-hailing services including tussle over poor pay and rising fuel prices. But while the introduction of e-hailing options into their buses could threaten their business models, it could also mean more income for the owners in the long run.

Budhabhatti says that in case buses aren’t able to bring enough riders initially, Little would ensure they “earn some minimum amount. We will take up that cost.”

Little and Swvl say they are working with national transport regulators to get better clarity on how their services will be operational. Kandil says they have seen “great traction” during the piloting, but in creating a middle ground between existing public transport and ride-hailing, they will need to convince commuters to change from arriving at bus stops and boarding a vehicle to booking one in advance.

Whether that behavioral shift will happen sooner is unknown, argues Budhabhatti, “but nonetheless, we want to give it a try and I have a feeling we will succeed.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox