Ring-tailed lemur

Taxonomy

- Order: Primate

- Suborder: Strepsirrhini

- Infraorder: Lemuriformes

- Superfamily: Lemuridae

- Genus: Lemur

- Species: catta

Ring tailed lemurs are Strepserhines (Streir, 2011). Strepserhines include such primates as Lemurs, Galagos and Lorises. The main characteristic seperateing Haplorhines (Monkeys, Apes and Tarsiers) and Strepserhines is a rhinarium (wet nose). Another charactersitic is the reliance on olfaction. Strepserhines tend to be more reliant on olfaction when compared to Haplorhines. Due to their dependence on olfaction they tend to have longer noses compared to Haplorhines ((Streir, 2011). Ring-tailed lemurs are part of the large group of Lemurs endemic to Madagascar. Approximently 12 species of lemurs are located in Madagascar. They range from 700 to 3800 grams. Lemurs tend to be diurnal, arboreal/semi terrestrial, large troops, female dominance, have a toothcomb, mulitmale groups and matrilineals.

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

Female dominace is exhibited by most lemur species and involves the ability for the female to consistently evoke submissive behavior from all males (Jolly, 1966; Richard, 1987; Kappeler, 1993). emale dominance can only occur in contexts of male submission (Hrdy, 1981). When males exhibit spontaneous male submission to females in the absence of female aggression, this is termed deference (Kappeler, 1993a). In the absence of male deferential behavior, females can elicit submissive male behavior through the use of aggression (Sauther, 1993).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

Another animal that has shown female dominance is the spotted hyena (Kruuk, 1972; Frank, 1989; Smale et al., 1993). However, they do not exhibit true female dominance, as seen in lemurs, since female hyenas do not consistently dominate males in all contexts (Smale et al., 1993; Frank et al., 1989). Jolly (1966) found most dominance interactions that occur among lemurs occur in the context of feeding and often occur with the female supplanting the males. Female lemurs will have feeding priority after winning aggressive interactions with males who submissively vocalize and retreat (Jolly, 1966, 1967, 1984).Ring-tail lemurs lack sexual dimorphism, both females and males are the same size (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Sussman, 2000).

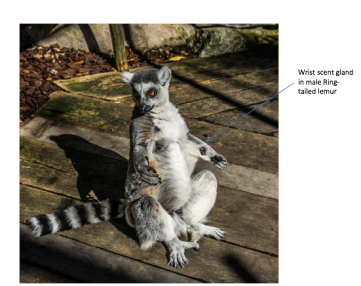

Males have scent glands within their wrist. The scent glands on the wrist have a horny epidermal spine that sticks out from a bare patch of skin on the wrist. They also have scent glands on their chest (just above their collarbone and close to the armpit) and anogenitally. Females only have scent glands located anogenitally. (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Rowe, 1996; Groves, 2001; Palagi et al., 2004).

They tend to be terrestrial and they often move via walking or running quadrupedally and holding their tails vertically (Mittermeier et al., 1994; Jolly, 2003). L.  catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs.

catta are endemic to southwestern Madagascar (Sussman, 1977). Madagascar is located 800 kilometers from Southeast Africa. It is the fourth largest island in the world (Swindler, 2002). Southern Madagascar is characterized by a rainy season that occurs from November to March (Jolly, 1966). L. catta are mainly found in forests of dry bush, gallery, deciduous, scrub and closed canopy forests (Mittermeier et al., 1994). L. catta are opportunistic omnivores and their diet mainly consists of fruit, leaves, flowers, herbs, other plant parts, and sap (Sauther, 1992; Mittermeier et al., 1994). Sauther (1992) found that 30% to 60% of their diet consisted of feeding on fruit and 30% to 51% of their diet consisted on feeding on leaves and herbs.

L.  catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999).

catta live in multi male, multi female groups ranging from nine to twenty two animals but on average have groups of fourteen animals (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Females are philopatric and males disperse; dispersing males tend to enter new groups with one or two other males from their original groups (Sauther, 1991; Sussman, 1991). Generally one female is the single highest-ranking female. The highest-ranking female is typically the one to initiate group movement in a certain direction (Jolly, 1966; Sauther and Sussman, 1993). Females form a dominance hierarchy in which certain females will out rank other females depending on the matriline to which they belong; however, every female is more dominant than males. These dominance relations are reinforced by agonistic encounters (Jolly, 1966; Taylor and Sussman, 1985; Gould et al., 1999).

Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999).

Males within these social groups are peripheral; however, there are often one to three central/dominant males. The male hierarchy is often dependent on age (Sussman, 1992). Generally the central males are more fit than other males, while the lower ranking/peripheral males are older, recently transferred males as well as younger males that have yet to transfer (Sussman, 1991; 1992; Gould, 1996; Gould et al., 1999). The higher-ranking males often have more interactions with females and thus are more likely to mate, but lower-ranking males also mate (Sussman, 1991, 1992; Gould, 1994, 1996; Gould et al., 1999).

Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).

Females start reproducing when they are two or three years old and generally havean interbirth ratio of 2 to 3 years (Sauther, 1991). Mating activity in a group will normally last for two to three weeks per year (Sauther, 1991), however, each individual female will only be sexually receptive for one to two days per year (Van Horn and Resko, 1977; Sauther, 1991).

Work Cited/ Read more

Altmann, J. (1974). Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour, 49(3), 227.

Frank, L.G.; Glickman, S.E. & Zabel, C.J. (1989). Ontogeny of female dominance in the spotted hyena: Perspectives from nature and captivity. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London 61: 127-146.

Gould, L. (1994). Patterns of affiliative behavior in adult male ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) at the Beza-Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar, Ph.D. dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis.

Gould L. (1996). Male-female affiliative relationships in naturally occurring ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) at the Beza-Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 39(1): 63-78.

Gould L, Sussman RW, Sauther ML. (1999). Natural disasters and primate populations: the effects of a 2-year drought on a naturally occurring population of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) in southwestern Madagascar. International Journal of Primatology. 20(1): 69-85.

Groves C. (2001). Primate taxonomy. Washington DC: Smithsonian Inst Pr. 350.

Hrdy, S.B. (1981) The woman that never evolved. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Jolly, A. (1966). Lemur behavior: a Madagascar field study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jolly, A. (1967). Breeding synchrony in wild Lemur catta. In Social communication among primates (S. A. Altmann, ed.) University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. pp. 3–14

Jolly, A. (1972). Troop continuity and troop spacing in Propithecus verreauxi and Lemur catta at Berenty (Madagascar). Folia Primatologica 17:335–362.

Jolly, A. (1984). The puzzle of female feeding priority. In Female primates: studies by women primatologists (M. Small, ed.) Alan R. Liss, New York. pp 197–215

Kappeler, P.M. (1993). Female dominance in primates and other mammals. In: Perspectives in Ethology, Volume 10: Behavior and Evolution. Bateson, P.P.G.; Klopfer, P.H. & Thompson, N.S. (eds.), Plenum Press, New York, pp. 143-157.

Kruuk, H. (1972). The spotted hyena: a study of predation and social behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Lewis, R. (2010). Grooming patterns in verreaux’s sifaka. American Journal of Primatology, 72(3), 254-261.

Mittermeier RA, Tattersall I, Konstant WR, Meyers DM, Mast RB. (1994). Lemurs of Madagascar. Washington DC: Conservation International. 356.

Pereira, M., Kaufman, R., Kappeler, P., & Overdorff, D. (1990). Female dominance does not characterize all of the lemuridae. Folia Primatologica; International Journal of Primatology, 55(2), 96.

Richard, A.F. (1987) Malagasy prosimians: female dominance. In Smuts, B.B., Cheney, D. L., Seyfarth, R. M., Wrangham, R. W., and Struhsaker, T.T. (eds,), Primate societies. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Sauther ML. (1991). Reproductive behavior of free-ranging Lemur catta at Beza Mahafaly Special Reserve, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 84:463–477.

Sauther ML. (1992). Effect of reproductive state, social rank and group size on resource use among free-ranging ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta) of Madagascar. Ph.D. dissertation, Washington University, St. Louis, MO.

Sauther, M.L. (1993). Resource competition in wild populations of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta): implications for female dominance. In Lemur Social Systems and Their Ecological Basis. P.M. Kappeler and J.U. Ganzhorn, eds. Plenum Press, New York

Sauther ML, Sussman RW. (1993). A new interpretation of the organization and mating systems of the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta). In Lemur social systems and their ecological basis. Kappeler PM, Ganzhorn J, editors. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 11–121.

Smale, L., Frank, L.G. & Holekamp, K.E. (1993). Ontogeny of dominance in free-living spotted hyenas: Juvenile rank relations with adult females and immigrant males. Animal Behaviour 46: 467-477.

Strier, K. (2011). Primate Behavioral Ecology. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

Sussman RW. (1977). Socialization, social structure, and ecology of two sympatric species of Lemur. In Primate biosocial development: biological, social, and ecological determinants. Chevalier-Skolnikoff S, Poirier FE, editors. New York: Garland Publishing. p 515–528.

Sussman RW. (1991). Demography and social organization of free-ranging Lemur catta in the Beza Mahafaly Reserve, Madagascar. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 84:43–58.

Sussman RW. (1992). Male life history and intergroup mobility among ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta). International Journal of Primatology 13:395–413.

Swindler DR. (2002). Primate dentition: an introduction to the teeth of non-human primates. Cambridge ( UK ): Cambridge University Press 284.

Taylor L, Sussman RW. (1985). A preliminary study of kinship and social organization in a semi-free-ranging group of Lemur catta. International Journal of Primatology 6(6): 601-614.

Van Horn RN, Resko JA. (1977). The reproductive cycle of the ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta): sex steroid levels and sexual receptivity under controlled photoperiods. Endocrinology 101(5): 1579-1586.

White, F. J., Overdorff, D. J., Keith-Lucas, T., Rasmussen, M. A., Kallam, W. and Forward, Z. (2007), Female dominance and feeding priority in a prosimian primate: experimental manipulation of feeding competition. American Journal of Primatology 69: 295–304.

Wright, P. (1999). Lemur traits and Madagascar ecology: Coping with an island environment. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 110(2), 31-72.