#WHM Collier Schorr

Throughout Women's History Month, we've paid an ode to the fabulous artists featured in our 11th issue, Women, by republishing our interviews with them. There would be no other way to end the celebration than with Collier Schorr, our leading lady of Women.

Collier Schorr dissecting desire

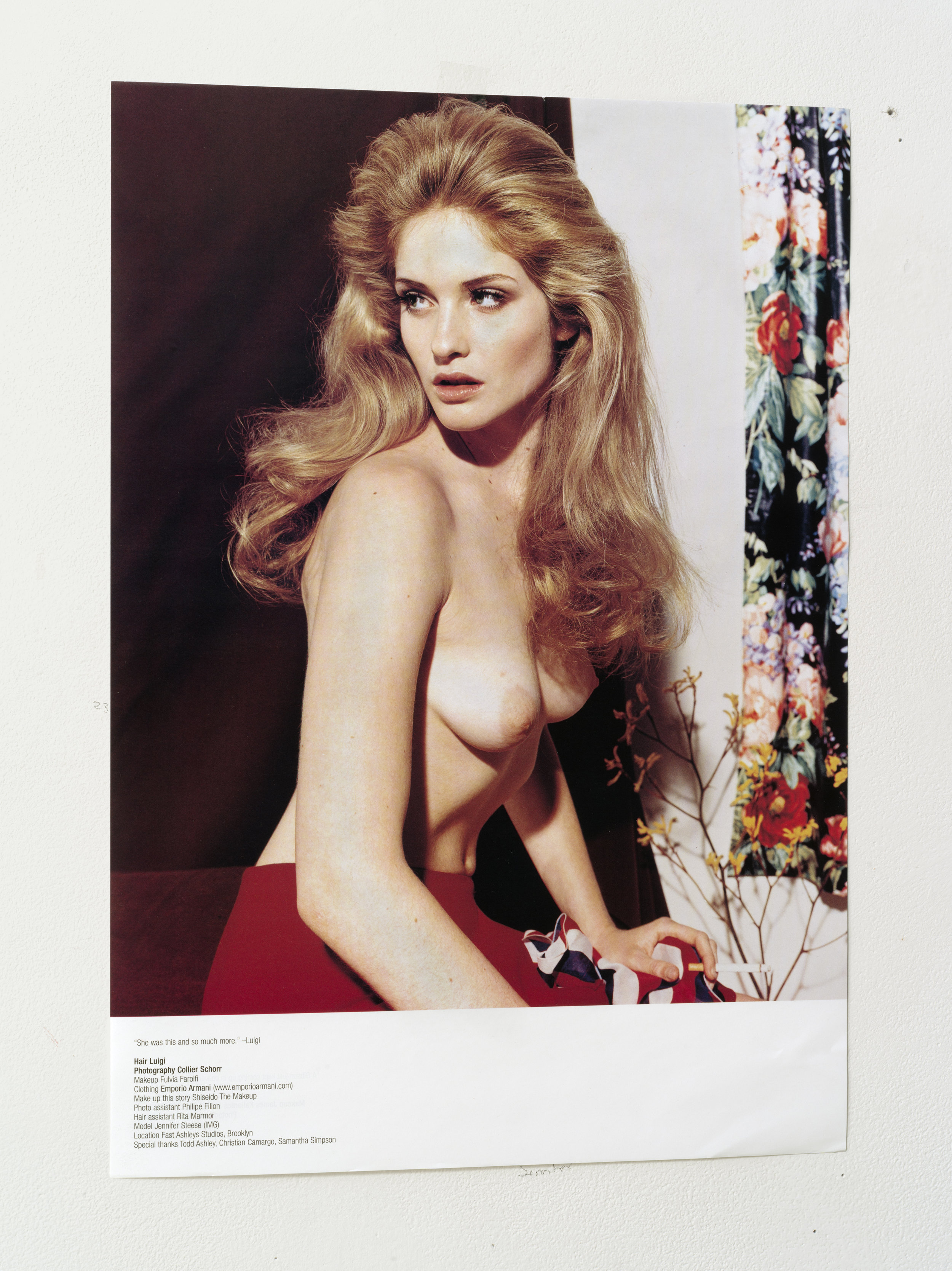

Portrait by Benedict Brink. All following images from the book 8 Women

Interview by Andrea Blanch

8 Women is your first book dealing specifically with women. However, you have had exhibitions that focused on women before (Other Women at Modern Art, London, 2006). Why did you decide to publish this book now?

It’s funny, I did a show titled Other Women years ago in London, and I loved the title. I always thought it would be my ‘women's book’ title because I’m a product of the early 80's and “other” was always on our lips. But that show was very focused on the Jens F series of work, which was heavily connected to Andrew Wyeth's Helga Pictures. In my project, Helga was played by a German boy named Jens until right at the end of the project. Then, I met a woman named Kate who looked exactly like Helga. For me, this was a real signal that avoidance of the female figure was not a solution to issues involving representation. Kate was a gateway to women, who for me suddenly became “women,” and not necessarily figures coded as “other.” So Other Women, as a show, was essentially Kate and Jens re-enacting poses that Andrew Wyeth was interested in. For me, that was my kind of education to classical poses. Half the work in my book and show from that time was a fight out of classicism. It’s complicated even for me. That show was a kind of opening of one door and closing of another.

You’ve mentioned before that within the traditional rubric of portrait photography that men seem ‘oblivious and safe’ under the pressure of documentary scrutiny, whereas women are more subject to sexualization and exploitation. Do you consciously seek to address how photography imprints its subject through the photographic gaze? Would using androgynous models be appealing to you in terms of navigating these paradigms?

It’s all very curious. If you shoot men, as I have done for years, you immediately gain attention from gay men who have been carrying the aesthetic torch for men for quite some time, like George Platt Lyons through to Peter Hujar and then Bruce Weber. For gay men, the interest in work is directly correlated to their attraction to the subject. Gay men have spent lifetimes sorting men into types. So there is the beef cake type, the hustler type, the black nude, the Latino hustler, and the Times Square Trick among others. Only recently did I start to find that what appears to be a democracy and an embrace of all skin colors and classes, is really just a very specific kind of objectification with all the nasty issues of power and dominance and general consumption. So maybe I changed my mind, no one is safe from the gaze of the camera. Then again, I always think people are safer in front of me. And I'm not sure if it’s because I'm a woman. Maybe I find my brand of looking ‘soft objectification.’ I love Peter Hujar's work because you can feel the communication. Maybe as I get older, I am driven by some combination of things. If the model brings an identity, I'm interested. And if they are open to playing a role, I'm equally open. I’m not a huge director. I enjoy watching. Androgyny is really something I'm attracted to as a look, dating to 1981, living in the East Village and loving the skinhead girls that hung out on Avenue A. A girl who looks like a boy is interesting, but so is a girl who looks like a girl, but is transformed by fashion. Clothing brings so much meaning. They are theatrical props basically. So, anyone can become another kind of figure.

Collier Schorr. The Business, 2002-2013

You are well known for your work in fashion photography. This collection takes many of your commissioned fashion photographs and puts them in a dialogue with other images. Can you explain this process and what it brings to your practice as a whole? What do you see as the main distinctions between your private work and your commissioned work?

The first fashion projects I did were for Purple Magazine and ID, and they were very much artists’ pictures using clothing. It was sort of appropriate at the time. Magazines were starting to look for artists to add something to a discussion and I think it made sense mixing in with the London folks like Corrine Day and Juergen Teller who were definitely doing something on the edge of documentary. After a few shoots with the kids in Germany, I started to work mainly in New York and more within the system of model agencies and stylists. Up until then I had styled the shoots myself. I would say during this time, there was a lot of separation between my artwork, things I was making for the gallery, the commercial, and things I was making for magazines and advertising clients. It was comfortable for me as I was still working in Germany every summer, so where my art practice was situated was clear to me. In 2009, I stopped going to Germany and I concentrated on fashion. I basically didn't feel like making art. I didn't feel like making those decisions about scale and materials. By the time I started contemplating another show, which would become 8 Women, I realized I had all these pictures from shoots that I was obsessed with that hadn't run in magazines. They were experiments I would make on the side, or moments I would take for myself, just to enjoy making a portrait. That’s when I realized that I had been working in a similar way as I had in Germany. As a director of a theatrical troupe that was engaged in scenes and scenarios with professional models, I had consensual partners who were informed participants and who benefited directly from the shoots, which is very different to using kids who have a lesser understanding about what the pictures could look like and no real investment.

So, the distinction is really the moment I move my camera left instead of right. It’s the moment I see something I know I won't give away, but I will keep for later. But, on an especially free shoot, like a recent project for Red:Edition magazine, I was basically directing as much as I could with a sense that I was making pictures I might show later. The only caveat is that a great picture worth looking at for a longer amount of time, well that happens in an instant. If I do 20 shots in a day and 100 frames for each shot, it’s not as if I will have 20 or even 200 shots. But, I want to keep them and think they say something I want to say. I am happiest when I see something happening I know I will want to explore later. But it is not satisfying if this is at the expense of what makes a good fashion picture for a fashion editorial. I am very conscious of what needs to be immediate and what needs to linger.

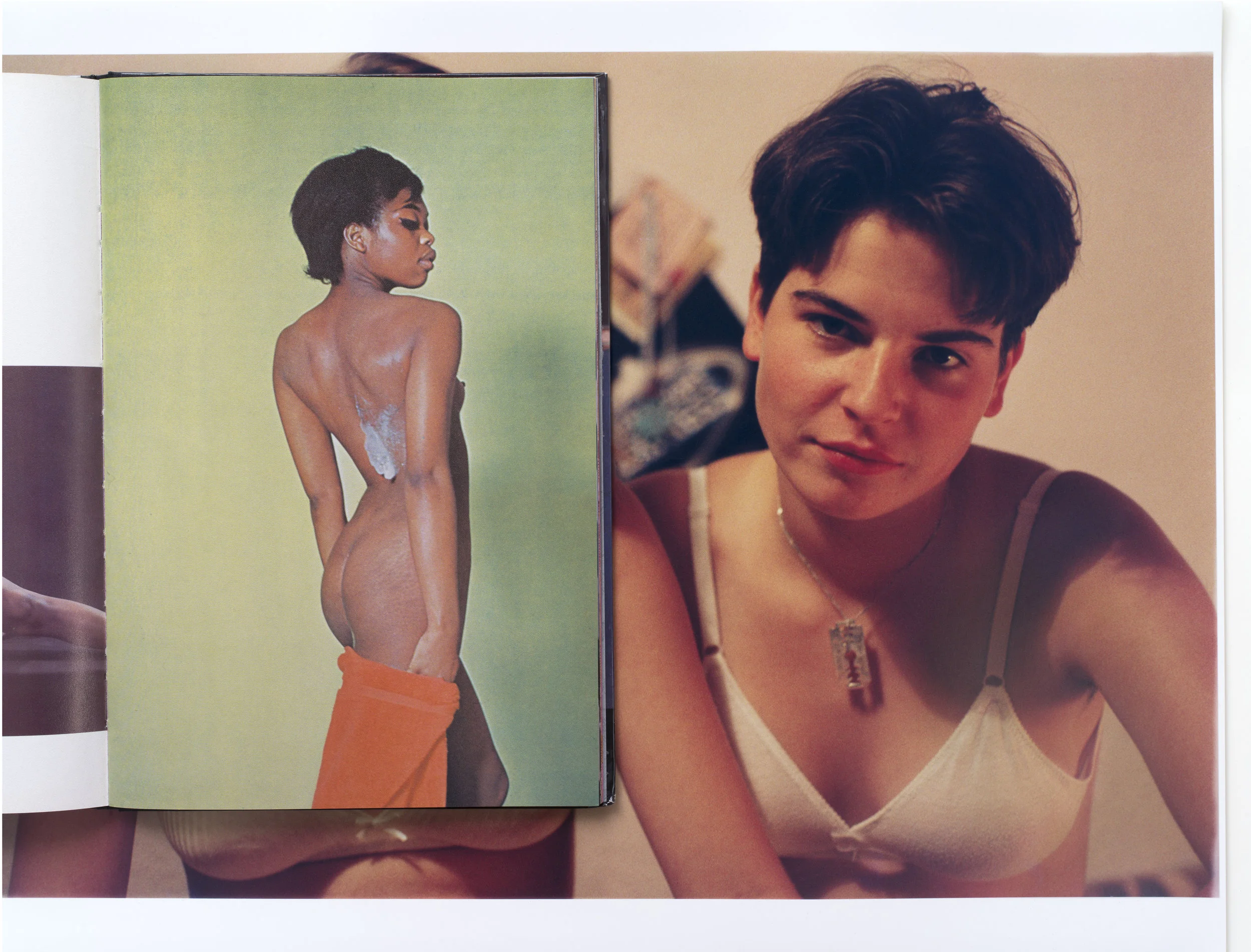

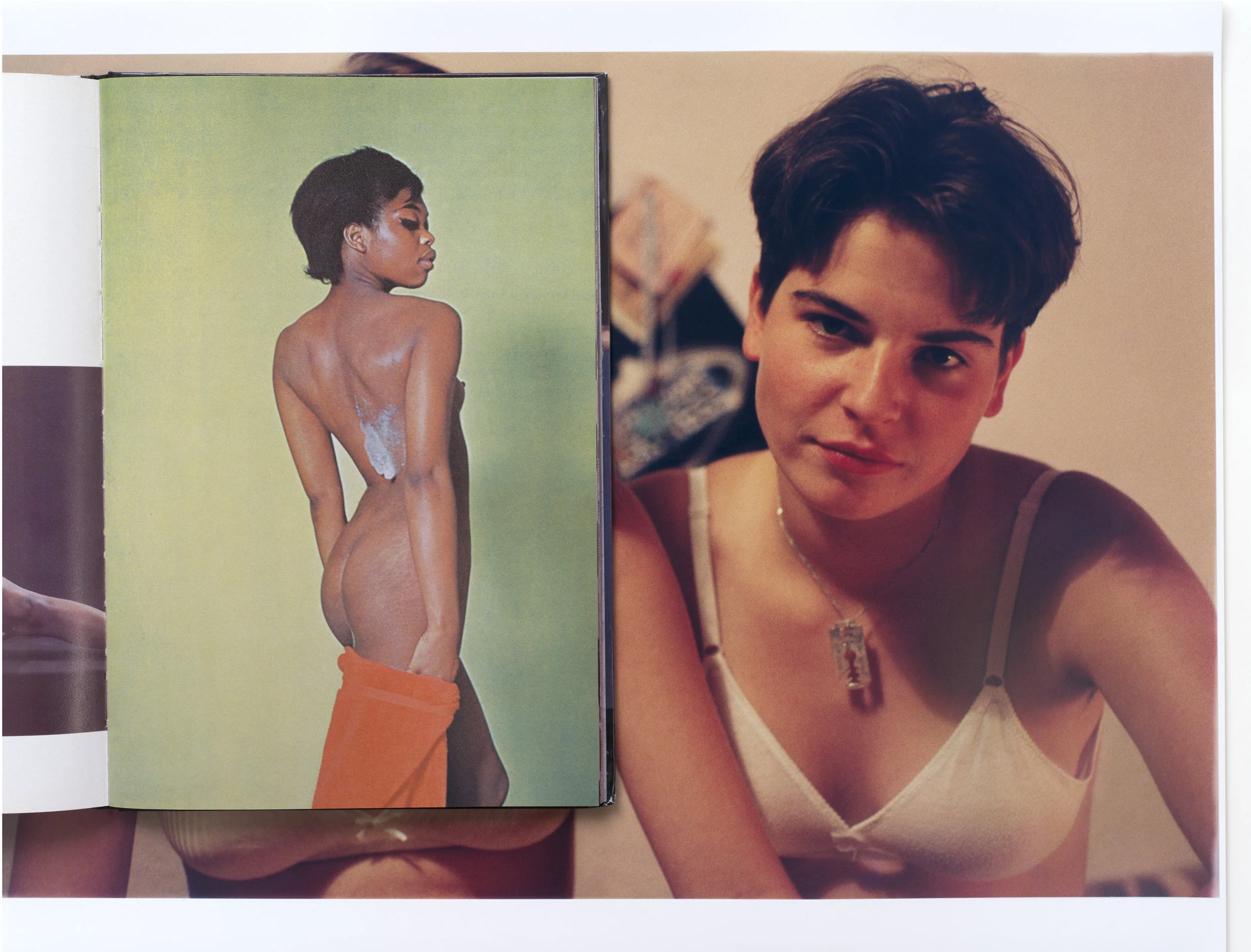

Collier Schorr. What! Are you Jealous? 1996-2013

The foreword to 8 Women explains your curiosity towards your female subjects’ desire to be admired. Don’t men also desire to be looked at? How does the middle ground of androgyny allow you to mediate this grey area, and what about androgyny is appealing for you in terms of navigating these conventions of gender and representation?

Well, of course this is my own philosophy. Not sure if any of it is really true or can really be broken down between the genders. In my experience, boys were less self-conscious because they weren't used to being looked at or admired. It was different though when I shot high school wrestling because they really were performers and had spent a lot of energy on molding their bodies to win matches. They loved being looked at. I guess historically, men didn't get things as a result of being looked at, whereas women did. However, I wanted to explore something aside from what one gets through approval, like how women feel when they are looked at, how desire is processed and appreciated, and the conduit between photographer and model, which can be satisfying to both parties. Men used to be admired by just gay men and that has changed. So, more and more, men have an idea of what it is to be looked at and how that can feel and what it can deliver. Certainly there are more boys now who look at magazines and imagine they could be in them. In the late 80's and early 90's it was Calvin Klein and not much else that could provoke male objectification. Now, boys without shirts are a dime a dozen in magazines.

Many reviews of 8 Women herald the book as “post-feminist.” Do you agree with this assessment? Is feminism something you consciously think about while creating your work?

I don't think it’s post-feminist. I read Ms. Magazine when I was 13, and I was clear on celebrating the word feminist. I don't think the goals and desires have changed. There was always a place in feminism to express a personal vision, and this is mine. My work is perhaps just a reaction to the so-called ‘post-feminism’ of the 80's art world, which molded me as a student. A lot of that so-called ‘post-feminist’ work— I'm not sure that was even a title the artists themselves liked—was an invention of the critics. And artists such as Kruger, Simmons, Charlesworth, and Sherman seemed very concerned and invested in a dialogue with the male gaze. The woman being looked at was essentially stripped of a voice, and the art-world was certainly picturing a very complicated dynamic between men and women. Also, I always felt the absence of a woman's dialogue with other women. It was all very heterosexual in discussion, as I recall. For gay women at the time, female desire seemed really barred.

Collier Schorr. Your Waist, 2014

You have talked before about the gay ownership of male sexual imagery. Do preconceived notions of identities through sexual orientation (i.e. masculine, feminine, gay, straight, dyke, fag, etc.) enter into your construction of images? Does your own sexuality frame how you author the images?

Maybe not so much. But that's just because of who I am, and not because of any rule. My orientation is maybe responsible for a certain taste, but that taste applies to both men and women alike and I'm interested in hyper-masculine and feminine as well as androgyny. Fran Lebowitz once said to me that men have a type and they will chase that fantasy forever, whereas women's desire is more flexible and accommodating. I respond as much to looks as I do to language. If I can't converse with someone, I'm less likely to get a good picture because I'm less confident overall. I see myself in the process of disappearing through photography and traveling through the lens to bind with the subject. I can fall in love over and over and connect over and over again. I'm very pro-monogamy in my personal life and see photography as a route to promiscuity—within the frames.

What unites your work thematically and how do you choose which images to arrange together? How has your work matured over time?

Sometimes, I think it’s movements, sometimes colors, and sometimes, through the training of layouts, editorials. It’s about eye contact versus looking away. I was so entrenched in German/Jewish history, the history of German photography, and the state of post-war Germany, that everything I did for a time could be traced back to that; be it August Sander’s solemnity, or riding boots on Nazi soldiers or on Charlotte Rampling in the film The Night Porter. In a way, fashion became Germany and I became a character that was traditionally male, chasing female glances like a straight man. Working on the book was so intensive because it was such an experiment. Weaving pictures together that were made in different time periods with very different expectations and certainly different skill sets. I never trained as a photographer. My dad is one, but he didn't teach me; he just gave me his old Rollei and said not to drop it. I’ve always felt, since when I started, I had no real technical knowledge, that a great picture or a good picture could be taken with any camera and could survive any number of mistakes. One picture in my book is a scan of a drug store print because I lost the negative. One survived the opening of the camera back. One is under exposed and one is roughly lit. On the other hand, there are pictures that have intricate lighting sceneries and are shot with a digital Hasselblad. I think maturing as an artist means respecting what you were able to do on instinct alone and never lose that. But try to capture everything with more nuance and always try to make pictures you are afraid won't look good. I’m constantly devastated and disappointed in shoots thinking I missed something, or that someone else would have done it better. I’m sure that what is awkward and potentially a failure has the most chance to rise. It’s the really good-looking pictures that can start to become dull. I love to make a conversation between the subjects in my work, either variations of one person, or in the case of a show, the women in the room interrogate and seduce each other. I love not being uptight and I aspire for that. That would be some kind of maturity perhaps.

Collier Schorr. Smoke, 1998

I love Richard Prince’s Instagram pictures. How do you think this kind of appropriation melds with yours—a male gaze taking female portraits versus a female gaze doing the same. In other words, how do think your gender does or doesn’t impact the finished product?

I find it incredible how Richard was able to repeat what he did with Marlboro, in which a commercial product/brand is turned into an art signifier. Now, any screenshot printed of anyone's Instagram post looks like art. In the same way that if you travel to Europe, where they may still have mural-sized billboards of Marlboro ads, it feels like you are in a museum. I look at one of those ads and I feel like I'm looking at an Andreas Gursky landscape. So, in that way, Richard’s appropriations are very flexible in suggesting any number of artists.

An architect told me a story about my work. He had been on vacation and a magazine with my pictures and an interview was on the bedside table. He read it all and was so excited to find a gay male artist who thought about some of the same things he did and that made photos that weren't so... basically gay male. He was saddened to find out I was a woman. Of course, he recovered. But at any given time, someone somewhere thinks I'm a German gay man. So, I'm not entirely sure people receiving my work know who took it, and in that way, it does meld with Richard’s ideas of authorship. So, I'm not even sure how I present myself. Every picture is a series of responses between the subject and myself. For all I know, certain women pretend I'm a man. I know that boys tend to feel good about it because they know that as much as I like them, I'm not going to try and get off with them. But a client once told me the boys are so into it because they think they can get me as I seem so enamored by them. I think this is ridiculous, but who knows. The perfect example I can relay is that once I took my favorite high school wrestler, Hudson, to a Rufus Wainwright concert. We sat on the wings of the stage and he sang along to all the songs. That was maybe my only date with a high school boy. It was perfect. I handed him back to his father when the show was over. He later got married and became the founder of Athlete Ally, a human rights action group focusing on tolerance in sports and awareness of LBGTQ issues and identities.

In terms of appropriation, I worked for Richard when I was 20 and I lived in his old studio for a few years. That was the biggest education I got for what I began to do. 8 Women certainly has its genesis in the idea of appropriation because I was flipping through magazines and retaking my pictures. And, I think I was also coming to terms with the scope of my subject matter, which sometimes felt like it was the cultural property of others.

Who has influenced you? While teaching at Yale, are there any young photographers who you find promising?

Helmut Newton and Richard Prince, but in a way, what does that say? Sylvia Plath and Janet Malcolm? James Baldwin gave me a sense of who I was before I knew, and Newton showed me who I thought I would fall in love with. The older I get, the more I feel affected by other artists with less fear of influence or comparison. Also, it becomes less about influence and maybe who you want to be in the same room with, your work that is. I love Sarah Lucas' work and feel a real affinity with her ambivalence about femininity. I miss teaching with Tod Papageorge at Yale. He was actually a great influence on me, just listening to him critique student work was great. That’s the important thing about teaching; the critiques belong to all photos. Whatever I say, I could be potentially saying to myself. I feel like I’m sounding like an alarm bell. All the young photographers are promising, because we never know who, when left to their own devices and perversions, will suddenly unveil a fantastic body of work. I, myself, had no idea I would be a photographer. I was supposed to be a novelist and when I realized that wasn't going to happen, I thought I would be a critic. And I was, but somehow I became a photographer because I had an idea and I decided to try it out.