by Jerry Fresia

Reprinted with permission of the artist

Every once in a while I come across an article that mirrors my own thinking on a certain topic, but has a different way of explaining it. With his permission, I am reproducing a post by Jerry Fresia. His discussion of the choices one has when painting the sun — whether to place the emphasis on value or color — is very similar to discussion in my books about how value affects color identity. His painting, Winter Glow, is also featured in my first book, Landscape Painting: Essential Concepts and Techniques for Plein Air and Studio Practice, on page 147.

Jerry Fresia runs art gallery and painting school that promotes the Impressionist experience in Lake Como, Italy. See his artwork, visit his blog, and find out more about his school at fresia.com.

If you paint the sun, you are always confronted with a specific choice: you either have to establish the correct value relationship by making the sun very light in value, or you must go for the color, in which case the value relationship will not be right, but the color relationship will be closer to the truth.

The reason for this is that the highest value pigment we have is pure white. (It is unlikely we would even use pure white because a daub of pure white would look “chalky” and artificial.) Once we add color, say, a tiny bit of cadmium yellow light, it looks more realistic, but the lightness of value is diminished by a tiny amount. If we were to then mix in small amounts of cadmium orange or maybe vermillion, we would probably get closer to the actual color of the sun (particularly if it were low in the sky). However, the value would get even darker. Such is the nature of paint as compared to actual light. So the choice is either to go for the value; that is, white with a tiny bit of yellow (which would be the lightest value/color note we could make), or to go for the color — a hot orange-red, perhaps. It’s one or the other. But together are impossible. Let’s use Monet’s famous Impression Sunrise to illustrate this point.

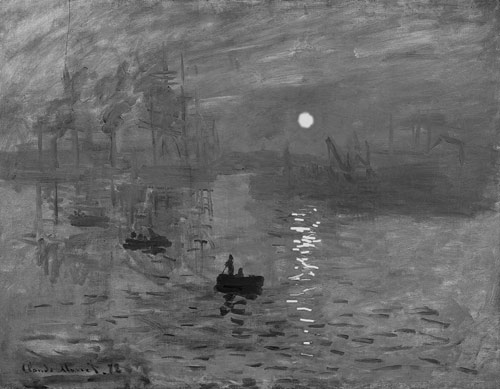

Above is the painting in color, and below, the same painting in black-and-white. Notice how the sun in the black-and-white version practically disappears. This is because in the actual color painting, the sun is the same value as the darker blue surrounding it.. Monet has sacrificed value in order to get the color. Let’s see what it would have looked like had he done the reverse, if he had sacrificed color in order to get closer to the proper value relationship.

In the color version below, I replaced Monet’s orangey-red sun with white and a tiny bit of yellow. Notice that in the black-and white-version below that, the sun is the brightest thing in the sky; the value relationship is relatively correct. But in order to get closer to the correct value, the richness of the color is lost. Here’s the point: there is no way to get rich color and light value with paint. Some artists (George Inness comes to mind) have made wonderful paintings where the sun is bright but weak in color. Monet, however, always seems to have gone for the color.

I am hopeful that this post will provide some food for thought without feeding a mechanical process that becomes formulaic. It is important, even necessary, to have knowledge, but when you are painting, the process must be also be driven driven by your experience of nature, as you resonate with the light. It would be unwise to say, “I’m going to approach it the way Monet did as opposed to the way Inness did.” Rather, wait until you get there. Open yourself to seduction. Will you get lost in the warm volcanic vermillion of the sun’s warmth or will you surrender to the bright dancing notes of a sparkling sun?

Additional Resources

Landscape Painting: Essential Concepts and Techniques for Plein Air and Studio Practice

How Value Effects Color Identity, pages 114–117

Playing Studio Detective with a Film of Monet Painting at Giverny

How to Suggest Brilliant Light Using Saturated Colors Instead of Strong Values Contrasts

The Affect of Value on Color Identity in Impressionist Painting

5 Comments

Thank you for article. Great food for thought. After many years of arguing that truth is in the black-and-white, emotion and “the moment” happens with color, I now always go for color when plein air painting. It just feels more exciting. Your article helps explain that to me.

http://www.carolhartman.biz

Once again a very informative article, thanks for that. I was particularly struck by your comments about resonating and vibrating with light as that is a foundational principle of the Sufi order with respect to the order of the universe.

Thanks for sharing this Mitch. It is highly suitable that the painting which caused the coining of the name for Impressionism be used here to demonstrate that copying nature as it was would have destroyed the “impression” Monet clearly felt and wanted to express.

This demo offers also the opportunity to reflect on an aspect of the physics of our eyes. We have that ability to focus on one degree, In space it is the diameter of the sun. Notice how little of the scene that represents! When we focus on the sun at sunset we are effectively casting everything else into peripheral vision. Ditto for each object in any scene that we carefully study. Our vision process is one of constantly zooming in and out with far more capability than any digital camera will ever have. One of the things a landscape painter has to decide is what section of the painting is going to be in focus and what will be in peripheral vision, dropping detail and value contrast in the latter. (The moon is 9/10th of a degree.)

I think it should be noted that what makes the spot in Monet’s painting a sun is color. We identify the sun as fiery red in a sunset or when the atmosphere is thick. Changing that spot to white immediately conveys the idea of a full moon. I see it that way.

Great insights Mitch! And great discussion here … really interesting and thought-provoking comments. Your posts are always inspiring, and tempt me to skip work and seek out my studio! Thanks again!