April 26, 2022

Zoe Zenghelis on Pursuing Creative Freedom

Rem was such an unbelievably original thinker. And Elia was such a wonderful designer. So the two together, along with our painting…I suppose it was quite a special group.

Molly Heintz: Why did you leave Athens for London in 1958, at age 21?

Zoe Zenghelis: I came from a very strict household––my entertainment was playing cards with Granny. So I was looking forward to getting out as soon as I could, and I was asking my parents to let me go and study. I wanted to do medicine, but they wouldn’t hear of it. Seven years of study or something like that for medicine? It was completely out.

My boyfriend Elia Zenghelis was here [in London] studying. My parents said, if you can stay in Athens for a year without seeing Elia and it’s still serious then, all right, we’ll think about [letting you go]. So that’s how it happened. We got married, and then I went.

I studied interior design at Regent Street Polytechnic. I wasn’t very pleased with the program because it was incredibly restrictive. The whole term we had to do one design––a kitchen––which drove me mad and was very boring. I decided to switch to stage design, which I enjoyed much more. The only problem was that again, it was very strict. Every term we had to do one play just as it was set in the book. But I wanted to do something modern. I decided that painting, which was the best department at that school, was the best thing for me as well.

MH: You met Rem Koolhaas when he was a student of Elia’s at the Architectural Association School of Architecture (AA) in London. Rem was married to Madelon Vreisendorp, an artist, and you all started working together under the name Caligari Institute [after the 1920 German Expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.] How did that come about?

ZZ: [Rem] was such a good pupil. He disliked every other unit at the AA, but he was very happy to be in Elia’s unit, and eventually they decided that we should work together. And that’s when we got very close, because Madelon, his wife, is a painter as well. Rem saw the paintings that I was doing while studying, and he said, “Why don’t you help us, too?”

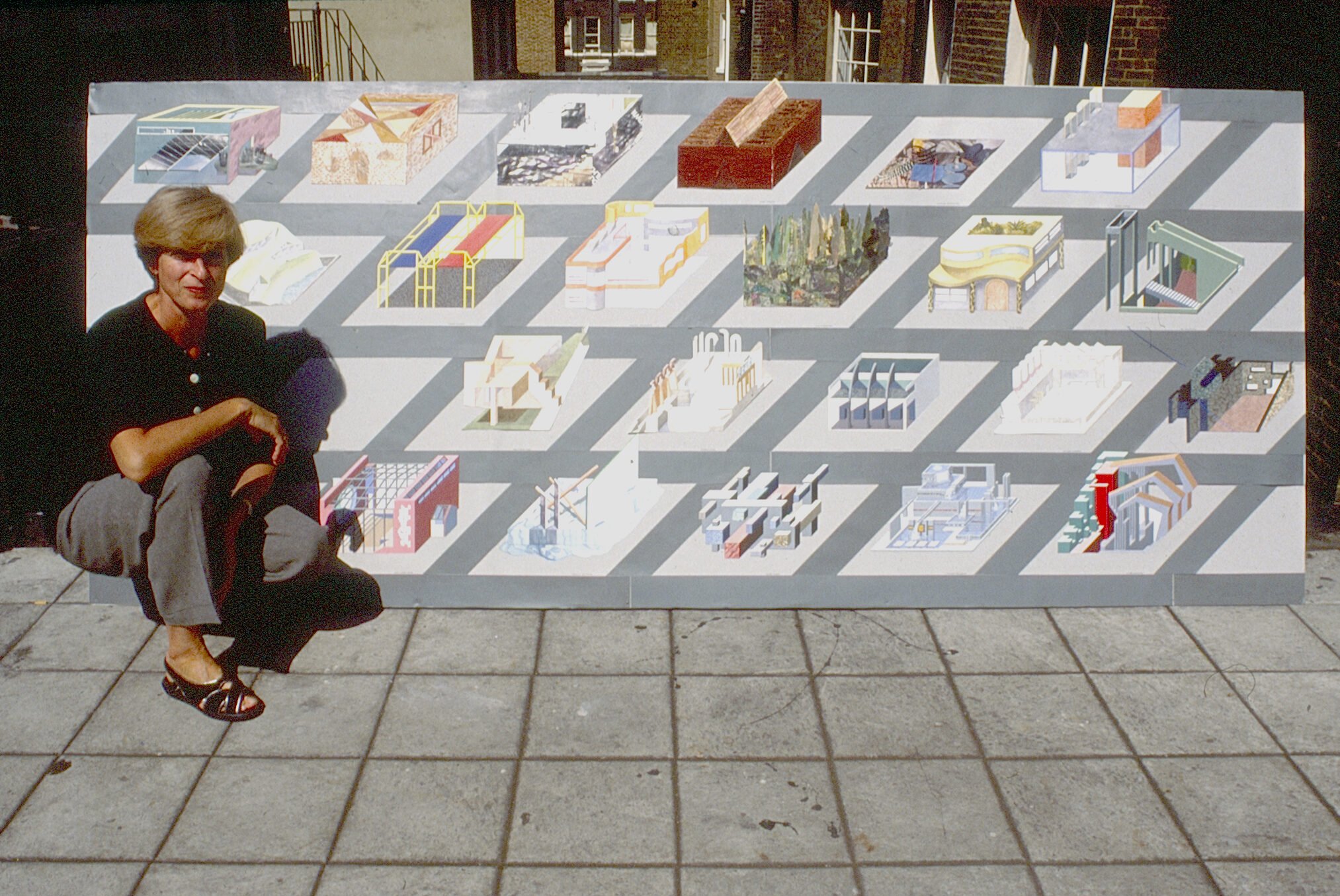

They went to America [in September 1972]. Elia was teaching with Rem there, and I remember that Elia wrote to me saying that “we had this amazing day of trying to find a name for the office.” “Caligari” was a joke, and they had to get serious. That’s when they decided on the Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

Rem was such an unbelievably original thinker. And Elia was such a wonderful designer. So the two together, along with our painting…I suppose it was quite a special group.

MH: In those early days, what was the interaction like? Can you describe how you all worked together?

ZZ: We worked in Rem and Madelon’s flat because it was bigger than ours and we were in these two big rooms. We [Zoe and Madelon] could hear [Rem and Elia] arguing or being very happy…and then they would come into our room and explain, and that was the beginning of a painting. Of course, we were trying to turn our paintings into exactly what the idea was, what the design wanted to do. That really made it more important than just coloring.

I remember [during one competition] Madelon was pregnant, and she was told by the doctors that she must breathe as much as she could. When you paint very fine things you hold your breath. But she was not supposed to stop breathing. So we were singing the whole time, painting and singing!

We had all these competitions. It was agony to finish, working until you hear the birds [in the morning] and then running to the post office to send it. But the thing was, we didn’t win any competitions! We’d already had exhibitions at MoMA, the Guggenheim, in France, and in Germany that were a success––we were in magazines, and all these paintings were bought. But we still hadn’t won any competitions. Those paintings allowed us to survive for a few years when we had no money at all and there was no work coming in.

MH: You’ve said, “Color is fundamental to our perception of the world. Surprisingly many architects are indifferent to it.” How did you come to teach the Colour Workshop at AA?

ZZ: Zaha Hadid was running the fifth-year program and she asked us to help her students with their end-of-term project. “They’re lost,” she said. So Madelon and I went and helped them organize and put color into their projects. After they finished, we were asked back to review them. It went so well and Zaha was so happy that Alvin [Boyarsky], the head of the AA at the time, asked us to start teaching there.

We were in the Communications Unit, which had etching, life drawing, and photography, and then our course was called the Colour Workshop. For the students it was great fun because it was the first time that they could paint. I think that every architect is a secret painter in life. You could see that if just a little thing in their lives changed, they could have been painters. But they became architects, and they were very restricted, because architecture is a line on white paper. [In the workshop] they were just free.

MH: I would imagine that was a very empowering workshop for many students, and, as you said, freeing, too.

ZZ: We wanted to stop painting from being an afterthought and to become a real part of the design from the beginning, which is very important. You think in color to start with. We started teaching them how to paint different materials—marble, glass, stone, wood. We let them apply [color] to some design of theirs, and then we gave them some designs of ours, empty of color and they only needed to make decisions about the materials. We had lectures, for example, about the psychology of color, which is also very important. If you want to mock, you can mock. If you want to be real, you can be real. You can make things grow and look much bigger. You can make them look much smaller. You can make them feel lighter. You have to know what light does on different materials and the texture. So you can learn how to retreat, to enlarge, to make things that look relaxed, or much more strong and vital.

MH: Architectural rendering today favors cinematic images with extreme detail, almost a sense of horror vacui. It’s such a contrast from your architectural paintings and your later work.

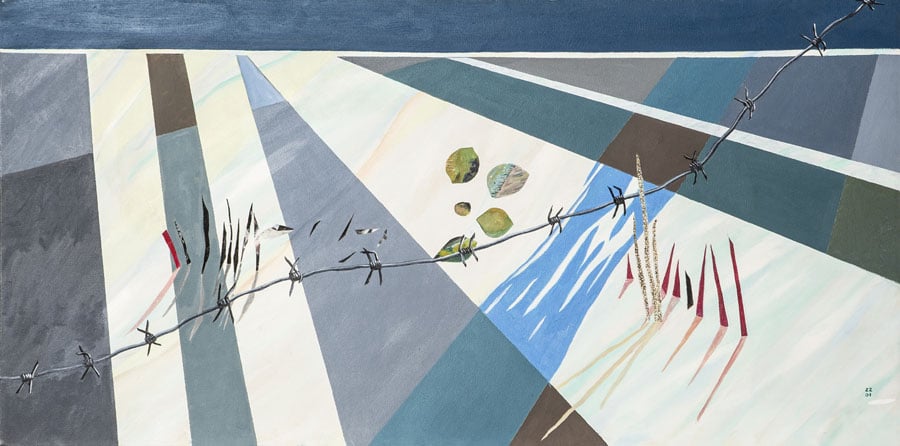

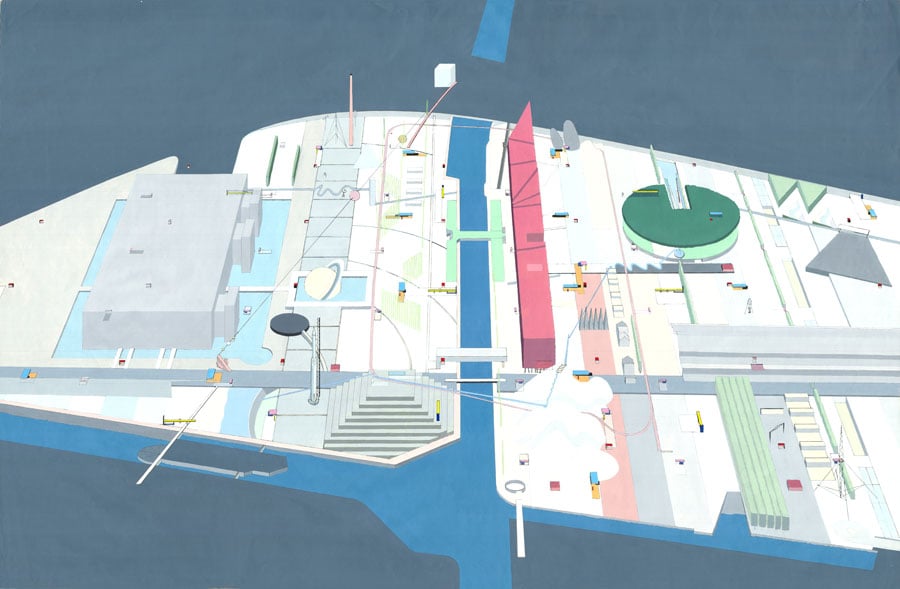

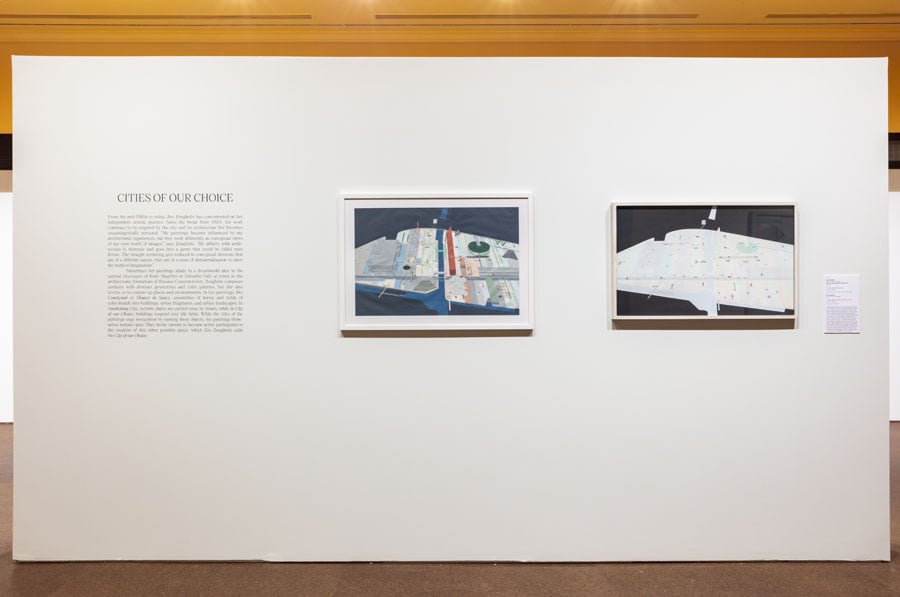

ZZ: [In the painting of Parc de la Villette] I wanted to take away all the things that are not needed but keep the things that I think I can use, that is the lines, the kiosks––which I didn’t show as kiosks anymore—and the colors. So [after the first competition painting], I made an abstract painting. You still could recognize La Villette, couldn’t you, from the map? But now it was all in all these very pale colors with only distinctions when they were greens for parks.

I’ve become absolutely fascinated with the relationships of things in my painting. It becomes more and more abstract. Shadows are not real anymore–they are shadows that fit the composition. And the composition in between the shapes is just as important as the shapes. So it’s this amazing arrangement and successful relationship of these things, of the line. I don’t know, I might change, but right now this is what is fascinating me. My objects go onto the architectural stage without being architecture.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Viewpoints

Google’s Ivy Ross Makes Sense of Color

METROPOLIS sits down with Ivy Ross, Google’s vice president of hardware design, to discuss Making Sense of Color, now on view during Salone del Mobile 2024.

Viewpoints

Two Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2024

The building industry makes vital moves toward standardization and transparency on energy efficiency and social impact.

Viewpoints

How the Design Industry Is Navigating the Sustainability Surge

Discover new ThinkLab research that suggests sustainable design is hitting its stride.