Posts Tagged ‘Palais des Nations’

Palais des Nations

Since December 2011, I have worked at the UN Conference on Trade and Development. My experience with the organisation has been contradictory: the admirable aspects tug against the repellent ones with equal force. For brevity, I can encapsulate my mixed feelings about the organisation by dissecting its name. On one hand, its “UN” prefix implies a progressive worldview and mission; and its “trade and development” suffix fits my professional interests. On the other hand, I find its acronym UNCTAD (just as bad in French – CNUCED) inconsiderate, and even brutal – a club of a word that fell, with a thud, out of long, inhuman committee process.

Despite my mixed employment experience, I have enjoyed my place of work. UNCTAD has its headquarters in the Palais des Nations, a building complex that is concurrently: a busy workplace; an architectural and historical monument and a self-sufficient mini-city.

Most visibly, the Palais des Nations is the UN’s European headquarters and the second largest UN centre after the one in New York. The Palais’s landlord is the United Nations Office at Geneva (UNOG), the Secretary-General’s branch office. UNOG maintains the Palais and delivers those invisible but demanding services, such as simultaneous interpretation, document translation and printing, which are indispensable to the UN’s intergovernmental activities.

Three large UN program organisations occupy most of the Palais offices: UNCTAD, the Economic Council for Europe (ECE) and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). A number of smaller organisations live there too.

Despite the many different subjects studied and activities undertaken in the Palais offices, its main product is conferences. The Palais is the world’s largest conference centre, hosting approximately 9,000 conferences per year. Along with participants from the public, the conferences are attended by Geneva’s silver-tongue horde – the largest group of diplomats in any city in the world.

Because of the Palais’s considerable conference and meeting facilities, other offsite international organisations also rent the bulk of its meeting rooms for one or two weeks a year for their annual member state gatherings. During these events, large parts of the Palais assume the identities of, for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) or the International Labour Organization (ILO).

The Palais’s acronym-heavy institutional identity is not overly interesting, nor is it easy to navigate. Even for UN staff, the organisational tangle of the UN is a bit like reading the following shallow-depth photo – I can locate my direct employer and link it to some of its sibling organisations, but once I branch out to the cousin-level layer of the chart, everything becomes blurry…

The Palais des Nations is also a historical monument: it is a pillar of Switzerland’s modern neutrality strategy and was the home of the League of Nations, the short-lived ancestor of the United Nations. The League had a schizophrenic beginning in 1919: US President Woodrow Wilson was its main architect but the US Senate prevented the USA from joining, more or less dooming it from the start. In 1920, Switzerland convinced the League to move from Paris, a war capital, to apolitical Geneva. To begin, the city housed the League in the lakeside Palais Wilson while it arranged a larger, more permanent home.

Here is a painter’s rendering of the League working in the Palais Wilson – the painting hangs on the third floor of the E building in the Palais des Nations:

Geneva offered Ariana Park as the site for a purpose-built complex. The Park is a 46-hectare property on the right (west) bank of the lake. The League received nearly 400 design proposals for the original building and, in the true spirit of multilateral diplomacy, it commissioned five of the competing architects, each from a different member country, and asked them to collaborate in building the “Palace of Peace.”

Construction on the original building began in 1929 and finished in 1938. Ironically, the Palace of Peace and its occupant never knew each other as whole entities. The membership and legitimacy of the League of Nations declined throughout the 1930s, such that when the Palace of Peace was completed in 1938, the League was effectively dead. In 1939, the remaining member countries wound up the League and shuttered the Palace of Peace, which remained empty throughout World War II.

After WWII, the five victor countries (now the five permanent member of the UN Security Council – China, France, Great Britain, Russia and the USA) created the United Nations in New York to resume the mission of the defunct League. In 1946, the UN Secretary-General signed a lease with the Swiss authorities for the Palace of Peace – now renamed the Palais des Nations – to be the UN’s European headquarters.

Here is a map of the modern Palais des Nations:

The original Palace of Peace structure comprised the Assembly Hall (building A on the map), the Library wing (B) and the Council wing (C and S). The grandiose Court of Honour fills the space between them and is visible from the many east-facing windows in the old buildings.

In 1952 UNOG added the little D building as temporary office space for the WHO while it built its headquarters just north of the Palais. From UNOG’s website about the Palais des Nations, I pinched this great photo from the early days of the Palais. It looks as if it was taken from where the D building is on the map, looking across the courtyard at the wraparound shape of the S building.

Photo source: UNOG, Palais des Nations web page

Today, most visitors to Geneva see the Palais from Place des Nations to the south, on the left side of the map. You may recognise a photo of the Place des Nations from the giant three-legged chair that stands at one end of it, across from the Palais entrance. Unfortunately, only staff with badges can enter through the Place des Nations gate.

For casual visitors looking in from this angle, the Palais is almost completely obscured from view, hidden behind a substantial security post and wall, and then a belt of trees. As such, most outsiders see only the famous approach, flanked by the flags of the 193 UN member states, that arrives at the southern periphery of the Palais. Here is a photo of that approach, shot from inside the security wall:

Delegates and visitors on organised tours enter through the western Pregny gate (at the top of the map), which houses the main security post. Below is a photo of the Palais’s driveway at the Pregny gate. Behind the gate you can see the back side of the Assembly Hall (building A).

To the left of the driveway is the pedestrian entrance. Staff use their badges to walk through a revolving gate; visitors must pass through a security scan and then queue for a temporary pass. The following photo shows the pedestrian entrance on a quiet winter morning – on busy days the queue can occupy the entire entrance area.

I do not know when the modern security measures were implemented, but they would certainly have received more attention after the terrorist attacks in New York in 2001. During 2006, for example, the UN tightened security after it received two warnings from the Swiss police about potential terrorist threats to the Palais.

Once through the Pregny gate, you arrive at the rear of the Assembly Hall and the premium parking lots adjacent to it:

From the above photo, if you continue down and to the left, you arrive at the E building, where I work. In 1973, UNOG completed the giant 10-storey E building, mainly as a headquarters for the new UNCTAD organisation, but also to add a number of new assembly halls and meeting rooms – it is still called the “new building.”

I work in office 9017 of the E building, with a view west to the Villa Bocage and, in the distance, the Jura Mountains.

I have a great view, but it pales in comparison to the sweeping panorama that the east-facing offices have of Lac Léman and the Alps, especially the offices on the upper floors. While my colleague Alexandra was on vacation last week, I snuck into her office to shoot the following photo from the window.

Geneva’s city centre is on the right of the photo, including its famous but hokey Jet d’Eau, with the cresting wave of Mont Salève (in France) as a backdrop. Moving left, you see the snowy French Alps in the distance, with Mont Blanc the most prominent among them. Interrupting the view of the snowy Alps is the nearby Môle (also in France) – the black pyramid in the centre left of the photo. The left side of the photo trails off into Cologny, the Beverly Hills of Geneva.

In the foreground of the photo, the Library block (B building) is on the right, and the green dome below is the roof over the E building’s assembly halls.

The four assembly halls in the E building are stacked two-by-two, to a height equivalent to four storeys of the attached office block. Each of them hold approximately 1,000 people, plus the platoon of interpreters, secretaries and ushers that service the big meetings.

Here is Room XIX on the third floor:

Next, here is a photo of the typical audio equipment at each seat: a microphone and an earpiece through which one can listen to simultaneous interpretation in any one of the six official UN languages.

There are also a number of smaller meeting rooms on the first and third floors. While the assembly halls host the high profile events, the smaller rooms suffer through some poorly attended meetings on mind-numbing topics. For example, at the recent ILO conference, several participants no doubt disappeared into the quicksand of the “Committee for the Recurrent Discussion.”

UNOG often displays temporary exhibitions in the common areas outside the E building’s assembly halls and meeting room. There is also an eclectic permanent collection of artwork donated to the Palais’s tenants over the years.

Here is one of several large murals of the same theme that decorate the first floor common area:

Most of the artwork is displayed on the third floor, of which here are a few examples:

In the last photo, you can see the large marble panels that are characteristic of the public areas of the “new building” (the walls of the offices on the upper floors are just drab stucco).

On the lake side of the E building, the second and third floors stop short of the edge of the building, forming two undulating mezzanine balconies that are used for catered receptions or temporary exhibitions. The mezzanines overlook perhaps my favourite part of the Palais complex, the Bar du Serpent – a large, bright café with comfortable chairs, a soaring ceiling and a great view. The Serpent is one of at least three beautiful cafés in the Palais. Other services in the Palais include: two banks, two travel agencies, two bookstores, two post offices, a cafeteria, a restaurant, a medical clinic, a general store…

The Bar du Serpent and the mezzanines above have a panoramic view of Lac Léman and its mountain backdrop through the four-storey windows that form the eastern wall of the conference complex. The mezzanines-café-window complex is called the Spence Halls.

Staying on the third floor, you can walk from the E building to the old building through an enclosed elevated walkway. You arrive in a hallway with soaring east-facing windows, a hallway that leads through all three wings of the A building. A dozen or so smaller meeting rooms are distributed along the satellite wings of the A building, bookending the main Assembly Hall.

The hallway windows look down across the Court of Honour to the Ariana Park, Lac Léman and the French Alps in the distance. Although the neoclassical architecture of the old Palais is grand and historic, I often find it blank and austere when seen from outside.

But inside, the Art Nouveau door and light fixtures are quite fitting and atmospheric. Below is a photo of a door to a small meeting room that bears the insignia of the League of Nations (Société des Nations in French):

Next is a photo of one of the light fixtures found throughout the old building’s main hallway:

Here is a photo of a different League of Nations insignia, this one adorning the large gates that open into the Salle des Pas Perdus (Hall of Lost Steps), which is the central concourse outside the main Assembly Hall:

Stories about the Palais during the League of Nations era inevitably describe the dark atmosphere in the Salle des Pas Perdus in the late 1930s, as war gathered and the League disintegrated. The dwindling number of member country delegates took breaks from interminable, hopeless sessions to stand and smoke in the Salle des Pas Perdus, whispering glumly among themselves as they stared down at their black shoes.

Those stories emphasise the darkness of the times, but ignore that the hall itself is filled with natural light throughout most of the day, and has an unsurpassed view across the grounds. Surely the glum League delegates in the stories must have occasionally looked up from their shoes and smiled at the view?

Here is a photo of the Salle des Pas Perdus, full of booths during the ILO’s recent annual conference:

And here is a photo that hints at the view from the concourse:

An odd detail in the photo is the entry displayed in livre d’or / guestbook in the foreground. The writing on the right-hand page is scratchy and difficult to read, but it appears to say thank you to the “Director” (the Director-General of UNOG?) and be signed by President Bouterse of Suriname. This is an odd, if not shocking entry to be on display, as President Dési Bouterse has clouds of dictatorship, murder and drug trafficking swirling around him. He ruled Suriname as a military dictator from 1980-7 and then, 23 years later, was elected president in 2010.

Bouterse has become steadily more politically toxic in the years since his dictatorship: he was convicted in the Netherlands for drug trafficking in 1999, a charge that was corroborated by US cables leaked by Wikileaks… his son Dino served three years for drug trafficking in Suriname from 2005-8… as sitting president he is on trial in Suriname for murders committed during his earlier dictatorship… and he recently pushed a law through the Suriname National Assembly granting amnesty for him and the other murder defendants – what on earth is the UN doing giving him a formal reception and then displaying his livre d’or entry? Bizarre.

Behind the Salle des Pas Perdus sits the main Assembly Hall, the Palais’s largest meeting room, holding up to 2,000 people. On the UNOG website, the UN speculates that the Assembly Hall may be the first room ever outfitted for simultaneous interpretation.

As the Palais’s flagship meeting room, the Assembly Hall’s evolution reflects that of the UN. When it was built in the 1930s, the Assembly Hall hosted but a small group of privileged (mostly male) international diplomats – the League of Nations had a maximum membership of only 58 member countries in 1935 and no one would have thought to invite the outside public to their sessions. It was consistent with the times for these diplomats to surround themselves in the relatively luxurious, isolated situation of the Palais, with its vast marble halls and numerous pieces of art. Even the doors to the Assembly Hall were extravagant: two giant bronze doors decorated with a representation of War and Peace.

With the transition from the League to the UN, the number of member countries eventually tripled to the current total of 193, and the total number of delegates grew by an even greater factor. Women played a growing role in the international diplomacy conducted in the Palais, and members of the public were also included. The number and size of the meetings hosted in the Assembly Hall, and in the Palais in general, grew to the point that the pomp and luxury had to give way to functionality. The Assembly Hall’s beautiful bronze doors were removed and fixed to the wall as a symbol of the bygone, ivory-tower era of international diplomacy.

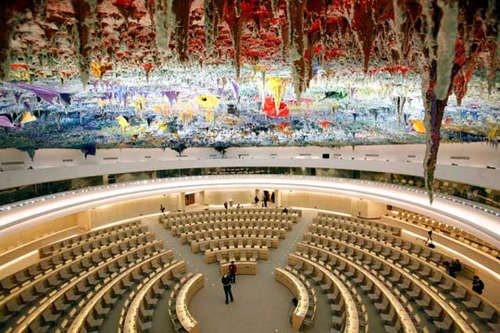

Unfortunately, I have so far been able to see three of the Palais’s more exclusive rooms. The first is Room XX in the E building, the ceiling of which is the tableau of a modern art installation by Spanish artist Miquel Barceló. I pinched the following photo, taken by the artist, from a Designboom magazine article about the piece. See also this video showing Barceló creating the work.

Photo source: Designboom. 2008. room XX by miquel barceló. 18 November. Available at: http://www.designboom.com/contemporary/miquel_barcelo.html [Accessed 19 June 2012]

The Spanish government paid for the installation and for the refurbishment of the hall, which was completed in 2008. In recognition of the Spanish donation, the UN inaugurated the refurbished room as the Human Rights and Alliance of Civilizations Room. The Human Rights Council has used the room fairly steadily in recent months, what with its annual meeting and the ongoing civil war in Syria, all of which means “no entry” for plebs like me.

Nor have I seen the Salle du Conseil, the original smaller chamber in which the League of Nations Council met. It is currently used by the Conference on Disarmament, a meeting perpetually troubled by lack of progress and, most recently, by its rotating chairmanship falling to the North Koreans. I pinched the following photo of the room from the Flickr page of the US mission in Geneva.

Photo source: US Mission in Geneva’s Flickr photostream

The third set of rooms I would still like to see are the delegates’ lounges. These are the small, comfortably appointed rooms in which high-ranking officials are received or cool their heels between sessions in the assembly halls. The rooms are often named after the countries that paid to decorate them: the Salon Français / French Lounge, the Czech and Slovak Lounge, etc.

These lounges are likely also where small groups of states strike the sensitive deals in secret during the larger public conferences. Indeed, in the 2003 lead-up to the war in Iraq, the press reported many stories of spying in the Palais. The USA, the UK and even Australia were keen to know how other countries would vote on the escalating resolutions against Iraq. At one point a British minister publicly admitted that her government had spied on Kofi Annan. In 2004 technicians found a bugging device in the Salon Français and Palais officials admitted that the complex was likely “full of bugs.” Analysis suggested the discovered bug was of either Russian or Eastern European origin. There were reports of two other bugs found in 2004, and another one in 2006.

In November 2010, Wikileaks published thousands of US State Department cables, which confirmed the USA’s efforts to spy at the UN in New York and Geneva. The cables include orders from Secretary of State Rice during the Bush years and then Secretary Clinton during President Obama’s first two years, instructing embassy staff to spy on diplomats and government officials from various countries, as well as on Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon.

None of this is particularly shocking, or even surprising: neither the spies nor their targets raise much of a fuss when spying is uncovered. But for all that member countries talk about the value they do or do not receive from their UN contributions in the form of meetings, projects or documents, it is fascinating to wonder how much they also consider the unmentioned value of being able to spy each other in the relatively lax security of these intergovernmental gatherings.

Moving from the most hidden of the Palais’s indoor activities back into the sunlight, the exterior of the old Palais is almost entirely built of light coloured marble, so that on a sunny day, it shines a blinding white. Here is a composite photo, taken on a spring morning, of the Court of Honour, with the Assembly Hall in the centre, the Library wing on the right and the Council wing on the left. You can click on it for a larger copy if you want to zoom in for a closer look.

While I acknowledge it is monumental, I find the outside of the Palais forbidding and inelegant – a poor architectural representation of the delicate and uplifting “world peace” missions of the League of Nations and the UN. In particular, the Court of Honour and the grand steps leading up to the Assembly Hall seem designed to march armies back and forth for a dictator’s review. My metaphor is perhaps a bit extreme, but over the course of the many times I have looked at the Court of Honour, my overriding sensation is akin to this:

Here are a couple more photos of the Palais façade, in which I tried to make it look pretty:

Despite its gleaming uniformity, the old Palais des Nations structures represent a challenge for UNOG to maintain. As a historical monument, it requires more money for renovations and upkeep than would a modern cement building. But in the snarled UN budgetary process, it is difficult to secure extra money for something as mundane as building upkeep. Member countries often pay to renovate specific meeting rooms and other visible, frequented parts of the Palais, but the forgotten bits and the general structure itself are somewhat neglected. UNOG managed to secure 618 million Swiss francs for an eight-year renovation project that began in 2010, but it says this is more or less the minimum for repairs, and is insufficient to modernise the sensitive parts of the Palais, such as the archives, which are apparently well behind international standards for document preservation.

Here is a photo of a cracked marble slab in the central Court of Honour:

Below the Court of Honour, the Ariana Park stretches down to the railroad and to Geneva’s Botanical Gardens. Here is the view from the Court of Honour:

In the pond in the foreground, you see the Sphère Armillaire (Celestial Sphere). It depicts allegorical representations of 85 constellations and was originally meant to spin and revolve like the heavens, powered by a small motor.

The Woodrow Wilson Foundation gave the Sphere to the League of Nations in 1939 as a memorial to the US President. In more ways than the Foundation likely intended, the Sphere symbolised Wilson’s doomed League of Nations. It only arrived in 1939, as the League was dissolving and World War II was already underway. During the six years of war that the Palais lay vacant, the Sphere proved unfit for inclement weather, alternately suffering water damage from rain and cracks from the cold. Its motor broke repeatedly and was abandoned as of the 1960s. In the photo below, you can see a large crack in the foot of the Sphere, bisecting the I and the L in the dedication to President Wilson.

Another bizarre monument in the Ariana Park is the Conquest of Space. The USSR donated it in 1971 in commemoration of “man’s success in conquering space.” Remember that the Soviets were the first to send a man into space, and neither the UN nor any other country had anything to do with that feat – why is this monument here?

On the lake side of the E building is a more recent addition to the Park: the Great Centaur statue, donated by Russia in 1997.

The Palais buildings and the major monuments in the Ariana Park date from the League and UN eras, and therefore represent those two organisations’ visions for a monument to international diplomacy. But the Park itself predates the League and therefore has a different feel.

A rich Genevan named Gustave de Revilliod de la Rive owned the property at the end of the 19th century. He served for two years in the Genevan cantonal legislature, but his real career was being rich: he spent his life travelling and collecting art. In 1877 he built a big manor on the west side of the property to house his collection, and named it the Musée Ariana, after his mother Ariane. The Ariana Museum was not included in the land given to the League of Nations, but nonetheless the Ariana Park and Museum share a name as part of the original estate.

Gustave de Revilliod never married, and upon his death in 1890, he bequeathed the Ariana Park to the City of Geneva. He had three conditions for the transfer: 1) the City was to bury him in the Park, 2) his prize peacocks were to continue to roam the grounds and 3) the Park was to remain open to the public.

Since the City of Geneva invited the League of Nations, and later the UN, to use Ariana Park, all parties honoured the first two of de Revilliod’s conditions: his tomb is one of the Park’s monuments, and peacocks continue to squawk, poop and preen on the grounds. But it seems that modern security concerns no longer allow the UN to keep the Park truly “open to the public.”

Among the pre-League heritage in Ariana Park are three 19th century villas: La Fenêtre (1820), Le Bocage (1823) and La Pelouse (1853). The Villa Fenêtre is not indicated on the map, nor have I ever heard reference to it. The Villas Bocage and La Pelouse now serve as office space for small departments – I am continually envious of colleagues with offices in these quaint, albeit drafty, little villas.

Here is Villa Bocage on a spring morning:

Followed by Villa la Pelouse on a summery evening – you can see a crisp Mont Blanc in the middle-left of the photo, and a sliver of Lac Léman in the bottom left:

Since the Palais des Nations is often an overly serious place, Gustave de Revilliod’s peacocks add important levity. For example, despite all of the stories about famous statesmen crafting important settlements, one of the most repeated stories, true or not, involves famously awkward Jacques Chirac breaking the leg of one of the peacocks as he stepped out of his limousine during one of his visits.

In fact, calling them “Gustave’s peacocks” is overly romantic: they do not reproduce enough to replenish their numbers, so the most recent generation descends from a donation by a Japanese zoo in 1997.

I encounter the peacocks only rarely, but through any open window in the Palais, you can hear their unbecoming squawks on most days. After exploring more with my camera, I seem to have found the daily morning hangout of one of the males – the volume of poop there suggests frequent visits.

I visited him on several different mornings, and each time we played the same game: he notices me, turns his bum my way, deploys his exotic plumage, and then thwarts my attempts to see his front by turning to keep his bum pointed at me. Eventually I give up and wait for him to turn around on his own.

Here are a few photos of the Palais’s most exotic and amusing resident:

I will finish with the most travelled part of the Palais that never appears in any photographs: the underground tunnel that travels the entire north-south length of the complex. But be warned – sooner or later, everyone gets lost in the tunnel…!