Carl Andre

by Jonathan Griffin

What is the most important thing to say about Carl Andre? Carl can’t remember. ‘What was it I once said?’ he responds when I ask him which, of all his contributions to the history of art, he is most proud of. ‘I didn’t make a great contribution but all I did was add the … It was something like …’ He tails off. ‘My mind is gone. I have no memory,’ he says simply and equitably. At 77, Andre is one of the most important living artists in America. Melissa Kretschmer, his wife, cuts in. She accompanies us throughout our conversation; nearly three decades Andre’s junior, she is better able to recall some of the details that evade her husband.

‘He truly changed sculpture,’ she says. ‘No,’ he corrects her, ‘I was one of those who did. There were other people working in the horizontal plane, I didn’t invent that.’ ‘OK, you’re my favourite artist then,’ she laughs. Andre continues, ‘Early on I learned it isn’t the artist who does something first who’s important, it’s the artist who does something last.’

To many in Britain, Andre is foremost the creator of what has become known as ‘the pile of bricks’: the sculpture titled Equivalent VIII (1966) that the Tate purchased in 1972 and which earned the Daily Mirror headline ‘What a Load of Rubbish’. Andre reminds me of the critical assessment gleefully. Public opinion seems to have mollified little over the years.

To others, especially in New York where Andre has lived in the same modest Soho apartment since the late 1970s, he is the artist who was tried and acquitted of artist Ana Mendieta’s death. Mendieta, his third wife, fell from a window in the apartment in 1985. Although his recollections of the event have been inconsistent over the years, he maintains his innocence.

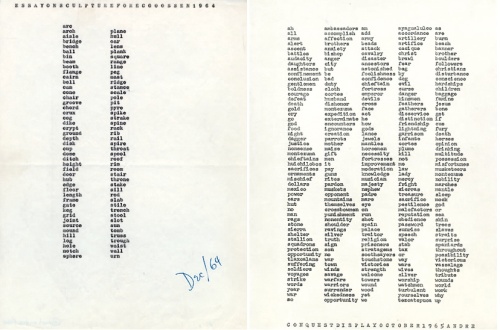

I am visiting him, however, to talk about his art, and to see if it is possible to tell his story without recourse to lurid biography. In May 2014 he will be recognised by a large-scale retrospective at Dia:Beacon, in upstate New York, his first in an American museum since the early 1980s. In the meantime, Turner Contemporary, in Margate, is currently showing eight of Andre’s sculptures and a selection of his lesser known typewritten poems in an exhibition titled ‘Carl Andre: Mass & Matter’, and the Tate is working on a catalogue raisonné of his poetry.

Andre once said, objecting to the Greenbergian model of formalist genealogy, that ‘Art works don’t make art works; people make art works.’ That was in 1978, before he’d been vilified by his community for events in his personal life. So I ask him: Does he still stand by the importance of artists’ biographies in understanding their work? ‘Absolutely!’ he replies. ‘What was it Henry Moore said?’ And he recounts an aphorism (or perhaps just a sentiment – I cannot find Moore’s original quote) that he will repeat three times during the course of our conversation. ‘An artist is a person who continues doing as an adult the things they learnt to do as a child.’

Andre’s childhood was in the blue-collar town of Quincy, Massachusetts. When he came to form the visual language that we now recognise as being distinctly his own, he was not thinking of the early Modernist grids of Piet Mondrian or Josef Albers. ‘I was thinking of the granite quarry. I was thinking of the immense shipyard.’ He never set out to be an artist. ‘I had these boyhood experiences which clicked with that kind of art. That kind of art didn’t start it.’

‘My grandfather was a bricklayer and a small contractor. [My family] were petty bourgeois craftsmen. So everything was about matter. Bricks, mortar, steel plates. My earliest memories were of these things. I had an uncle, John, who didn’t have any children and he would appear in the morning before I went to school and he would pick me up and he would take me to his work sites. And there I was playing with bricks on building sites; I was exposed to these materials continuously as a little child. I didn’t live a suburban life.’

Nevertheless, his mother was socially ambitious, and his father passed on a love of poetry. ‘My father read Byron and Keats and Shelley at night. And I remember I was sitting in his lap, and he’d have a glass of sherry, and he’d read these poems to me, and every once in a while I’d say “What does that mean?” And he would say, “You’ll find out.” In other words, he didn’t shape me in that way.’ Instead, it was the sight of words lined up on the page that most deeply impressed the young Andre.

I ask him what his mother thought of his art. ‘Ah, delicate subject, delicate subject. When I visited my family I would come in and say, “Mother I’m having this show, in such and such a gallery, and I can show you the reviews,” and my mother said “No! I don’t want to see that!” She said “I want you to carve a seagull!” I said “Mother I couldn’t carve a seagull.” And she would cry and cry. She was a Stalinist from head to foot!’

Was he ever afflicted by class guilt? ‘Guilt? Why? We were lower middle class!’ But you were leaving that behind, I say. ‘Not really, I never left that behind. I never had social aspirations, I never wanted to be among the rich. I had a small exposure to the rich and I didn’t like them. Because they’re entrapped by their money.’

He gestures to the area beyond the wide window, looking south over Manhattan. ‘Soho, this area here, when I first lived in New York, was called Hell’s Hundred Acres. It was full of these lofts which had been sweatshops where you had all these girls working far below minimum wage and being victimised with every conceivable debauchery.’ How did that affect your art? I ask. ‘It’s a question of haunting more than anything else. Somehow I got the idea that there were no innocent actions in the world.’

Do you consider yourself a feminist? ‘Oh yes. Absolutely!’ he replies without hesitation. I ask him what that means for him. ‘Well, I believe that women are essentially superior to men. Because women are biologically devoted to life. And the maintenance of life. Women are caring, men are off in the corner jerking off and trying to see who has the biggest cock. Men are a hugely competitive group. I’ve never been gay, but I’ve always preferred the company of women because men are so pettily competitive. You can see it with school kids. There’s all this rough-housing, where the bigger kids beat up the little kids. Well I was a fat kid, and I was subject to a lot of abuse when I was little. My mother told me never to hit anybody. So I couldn’t box. […] If somebody came up to me like this’ (he raises his fists) ‘I would grab their hands and wrap around them and fall on top of them. I was fat. Then I would lie on top of them so they were paralysed. And I never said, “Will you give up?” I was a smart kid. I always said, “Can we stop?” Because if I said, “Do you give up?” that means I have an enemy for life.’

Andre, in old age, is a gently sympathetic character. It is easy to imagine him as the stumpy brain-box, the bullied fat-kid, helpless in quarrels but probably not making things easy for himself. His voice rises to a high pitch when he’s pressing a point. In the blue dungarees that he’s worn since the 1960s and his white chin-strap beard, he seems gnomish, animated and quick to laugh, but retaining the puritan manners of his Massachusetts upbringing.

Are you saddened, I ask him, by the charges of machismo that are often levelled at you and your work? ‘It’s ridiculous!’ he exclaims. (That high voice again.) ‘Women who know me very well know that I’m not a male chauvinist. If anything I’m a female chauvinist.’ I say that, to me, the majority of his sculptures have always seemed profoundly vulnerable. Instead of the uncompromising cohesion of a bronze cast or marble carving (I’m thinking of Moore, again, but also Rodin, Brancusi and David Smith – all professed influences) Andre’s unfixed composite sculptures are constantly threatened by dispersal. Despite his use of industrial metals and timber, Andre points out that ‘one of the things that has ruled my work is the fact that the things that I use to make my work – the particles – had to be of a size that I could move myself.’

There is a humility to his sculpture. ‘I’ve never made a gold piece or something like that,’ he says. ‘I’ve wanted to use the six common industrial metals. Aluminum, copper, iron, magnesium, lead and zinc. They are reasonably priced. You could use something like titanium but titanium is spectacularly expensive.’ In addition to which, of course, Andre was one of the first artists to allow his art to be walked on, thus eliminating the objective distance between artwork and viewer and subverting sculpture’s longstanding association with monumentality.

Despite these sculptural principles, which were informed by his leftist political convictions, Andre’s work has never been populist. ‘When I started doing my work, the question was “How can you call this art?” It wasn’t accepted and it wasn’t accepted for a long while. Probably the majority of Americans still think, “How can you call this art?”’ It is remarkable, I say, how difficult the work remains for so many people, half a century after much of it was made. ‘It’s because it’s so simple!’ he says. ‘With each generation the struggle is the same. There is no progress in art. It just keeps on going. I can’t say my work is better than Stonehenge – that’s impossible! The thing is people die and other people are born. Little kids have to learn the facts of life. Nobody’s born with knowledge. We’re born with original sin but not with original knowledge!

‘I never intended my work to be controversial,’ Andre says. But you didn’t modify it either, I say, even when some pieces, such as 37th Piece of Work (1969), made for the foyer of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, won the popular applause that others like Equivalent VIII have never known. Who do you make art for? I ask him, even though I already know the answer. ‘Me,’ he replies, instantly and simply.

How then, I wonder, does he feel about the renewed attention he will receive when the Dia show opens next year? ‘I accepted it only under the condition that I make no contribution to it whatsoever. [I told the curators] I’m not going to tell you what to borrow, I’m not going to tell you how to arrange it, I said “Étonne-moi!” – astonish me.’ He trusts curators Philippe Vergne and Yasmil Raymond implicitly, and looks forward to seeing how they will situate his work in their space.

‘I feel very remote from it. Each work of art is like a love affair that’s come to an end. It’s over with. It was rewarding at the time but you can’t live in the past. That’s the way I feel about my work. I don’t feel I could go back and do it again – it’s been done. So I think of myself as retired, and I have for quite some time now.’

Andre wasn’t always so placid about the contextualisation of his work. When curator Barbara Haskell included him, against his will, in the survey ‘BLAM!’ at the Whitney Museum in 1984, he published a point-by-point rebuttal of the assertions she had made in her catalogue essay. Another time, the artist Sylvie Fleurie placed women’s shoes on a floor piece by Andre for a museum exhibition in Esslingen, Germany. ‘Oh she was a monster!’ says Andre, who demanded her intervention be removed. ‘She thought I was oppressing her as an artist. And as a woman. And in every other possible way. I said, “Well you’re oppressing my art!”’ I suggest, tactfully, that with an appropriation artist like Fleury, it’s a complicated situation. ‘No, it’s parasitic.’ Does he feel the same way, I wonder, about the work of artists such as Richard Prince? ‘What does he do?’ Well, I say, for certain works he rephotographs advertising imagery. ‘Oh well that’s garbage anyway.’

Like many artists, Andre has strong views about the work of his peers. ‘I am in some quarters considered one of the founders of Conceptual Art. And I HATED Conceptual Art. Even though I was good friends with people like Lawrence Weiner and Joseph Kosuth. But I said to Weiner, “Lawrence, you’re a great poet.” And he HATED that! Because I think to this day that an idea, something in the head, is not a work of art, not a sculpture, until it’s IN the world. And THEN it’s a sculpture. But there’s no such thing as a sculpture in the head. […] Ideas to me are a dime a dozen.’

Critics and theorists too have fallen foul of Andre’s wrath. ‘Conceptualizing inkpissers’ is what he’s called them in the past. ‘What I hated was critics who interpreted my art according to the latest fashion. Especially when Conceptual Art came along. They said I was a founder of Conceptual Art, and I kept on saying to people, “There are no ideas under those plates! No ideas, just desires.”’

I could quite easily do the same in 2013, I say. It is tempting to talk about Andre’s work as ‘relational’, as social sculpture in which the dynamics of participation and engagement are played out in gallery or site-specific locations. Andre has even referred to himself, with a hint of irony, as the first ‘post-studio’ artist. When did you last have a studio, I ask him? ‘I’ve never had a studio. Ever.’ So if you couldn’t try things out, were there occasions when you assembled things in a particular space and it didn’t work? ‘Always,’ he responds. ‘There have been times when I was offered a show and I had the material and was in the gallery and I just couldn’t do anything. That’s happened.’

This attitude of acceptance is typical of Andre, who views his life as a product of fate. Quincy, his parents, the New York art scene of the 1950s and ’60s, his turbulent love affairs – all these experiences have fed into his ‘simple’ art, though we don’t necessarily need to know about them in order to appreciate it. He recalls Ulysses’ statement in the poem by Tennyson, ‘I am a part of all that I have met,’ but then amends it to ‘All that I have met is a part of me.’ ‘I am a narcissist,’ he explains.

‘I feel like my life has been like a cork bobbing on the waves. I don’t think I’ve ever made any conscious choices in my life, I’ve just been – not driven, but thrown into the tide.’

First published: Apollo, March 2013

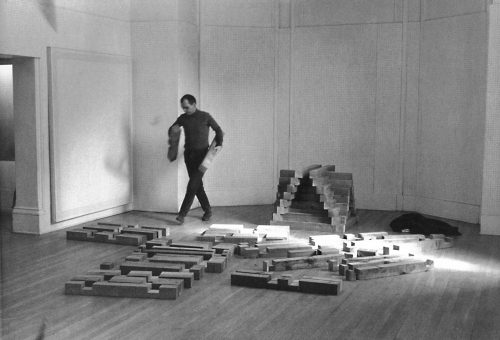

[…] Fig. 8. Carl Andre building “Cedar Piece,” 1964 (Image: Jonathan Griffin) (https://jonathangriffin.org/2013/03/18/carl-andre/) […]