Hello guys. Hoping you all are continuing to stay safe from the Coronavirus. There have been positive and negative news from around the world. United States and Spain continue to witness high number of casualities while Italy has began to recover. France and United Kingdom are also witnessing increase in number of cases day by day. But, we can expect some positive news from UK as a new vaccine has been developed by Oxford University and Plasma Therapy has also been successful in the recovery of few patients. Plasma Therapy is set to be tested on more patients and we can expect a higher recovery rate in the coming days. Germany, Switzerland, Austria, South Korea, Denmark, Australia and New Zealand are seeing increase in their recovered cases in their list. Mauritania was the first country to recover completely from the virus while Saint Lucia was the first country to have 100% recovery rate without reporting a death. Greenland and Saint Barthelemy also was CoVid- free by the time I published the previous post. Since then, Yemen and Anguilla have recovered completely from the virus without reporting a single case. Yemen reported only a single case while Anguilla had 3 cases. Today. we are keeping the Central American Heritage Tour on hold and moving to a different region. If you ask me what was the reason for sudden change of place, I don’t have any answer. I just felt like changing the focus. From Central America, we are moving back to Central Asia and to one of the coldest countries in the world- Mongolia. We are going on a tour of one of the Cultural Landscapes that witnessed different rulers of the Mongol Empire- Orkhon Valley.

Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape (Mongolian: Орхоны хөндийн соёлын дурсгал, romanized: Orhonii höndiin soyoliin dursgal ,Mongolian Script:ᠣᠷᠬᠣᠨ ᠤᠬᠥᠨᠳᠡᠢᠶᠢᠨᠰᠤᠶᠤᠯ ᠤᠨᠳᠤᠷᠠᠰᠬᠠᠯ) sprawls along the banks of the Orkhon River , some 320 km west from the capital Ulaanbaatar. For many centuries, the Orkhon Valley was viewed as the seat of the imperial power of the steppes. The first evidence comes from a stone stele with runic inscriptions, which was erected in the valley by Bilge Khan, an 8th-century ruler of the Göktürk Empire. Some 25 miles to the north of the stele, in the shadow of the sacred forest-mountain Ötüken, was his Ördü, or nomadic capital. During the Qidan domination of the valley, the stele was reinscribed in three languages, so as to record the deeds of a Qidan potentate. Mountains were considered sacred in Tengriism as an axis mundi, but Ötüken was especially sacred because the ancestor spirits of the khagans and beys resided here. Moreover, a force called qut was believed to emanate from this mountain, granting the khagan the divine right to rule the Turkic tribes. Whoever controlled this valley was considered heavenly appointed leader of the Turks and could rally the tribes. Thus control of the Orkhon Valley was of the utmost strategic importance for every Turkic state. Historically every Turkic capital (Ördü) was located here for this exact reason. There were many houses by the bank but they are all gone now. The 121,967-ha Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape encompasses an extensive area of pastureland on both banks of the Orkhon River and includes numerous archaeological remains dating back to the 6th century. The site also includes Kharkhorum, the 13th- and 14th-century capital of Chingis (Genghis) Khan’s vast Empire. Collectively the remains in the site reflect the symbiotic links between nomadic, pastoral societies and their administrative and religious centres, and the importance of the Orkhon valley in the history of central Asia. The grassland is still grazed by Mongolian nomadic pastoralists.

The archaeologically rich Orkhon River basin was home of successive nomadic cultures which evolved from prehistoric origins in harmony with the natural landscape of the steppes and resulted in economic, social and cultural polities unique to the region. Home for centuries to major political, trade, cultural and religious activities of successive nomadic empires, the Orkhon Valley served as a crossroads of civilizations, linking East and West across the vast Eurasian landmass. Over successive centuries, the Orkhon Valley was found very suitable for settlement by waves of nomadic people. The earliest evidence of human occupancy dates from the sites of Moiltyn Am (40,000- 15,000 years ago) and “Orkhon-7” which show that the Valley was first settled about 62,000-58,000 years ago. Subsequently the Valley was continuously occupied throughout the Prehistoric and Bronze ages and in proto-historic and early historic times was settled successively by the Huns, Turkic peoples, the Uighurs, the Kidans, and finally the Mongols. Within the cultural landscape are a number of archaeological remains and standing structures, including Turkish memorial sites of the 6th-7th centuries, the 8th9th centuries’ Uighur capital of Khar Balgas as well as the 13th-14th centuries’ ancient Mongol imperial capital of Kharakhorum. Erdene Zuu, the earliest surviving Mongol Buddhist monastery, the Tuvkhun Hermitage and the Shank Western monastery are testimony to the widespread and enduring religious traditions and cultural practices of the Northern School of Buddhism which, with their respect for all the forms of life, enshrine the enduring sustainable management practices of this unique cultural landscape of the Central Asian steppes. The inscribed property straddles the Orkhon River, which provides water and shelter, key requisites for its role as a staging post on the ancient trade routes across the steppes and for its development as the centre of the vast Central Asian empires. Specifically, the inscribed property provides evidence of the 6th-7th century Turkish memorial sites, the 8th-9th century Uighur capita of Khar Balgas, the 13th-14th century Mongol capital of Kharkhorum, the earliest surviving Mongol Buddhist monastery at Erdene Zuu, the Hermitage Monastery of Tuvkhum, the Shankh Western Monastery, the palace at Doit Hill, the ancient towns of Talyn Dorvoljin, Har Bondgor, and Bayangol Am, deer stones and ancient graves, the sacred mountains of Hangai Ovoo and Undor Sant and archaeological and ethnographic evidence attesting to the long and enduring tradition of nomadic pastoralism. Let us have a tour of some of the monuments of the Valley.

The Orkhon inscriptions also known as Orhon Inscriptions, Orhun Inscriptions, Khöshöö Tsaidam monuments (also spelled Khoshoo Tsaidam, Koshu-Tsaidam or Höshöö caidam), or Kul Tigin steles (simplified Chinese: 阙特勤碑; traditional Chinese: 闕特勤碑), are two memorial installations erected by the Göktürks written in Old Turkic alphabet in the early 8th century. They were erected in honor of two Turkic princes, Kul Tigin and his brother Bilge Khagan. The inscriptions, in both Chinese and Old Turkic, relate the legendary origins of the Turks, the golden age of their history, their subjugation by the Chinese, and their liberation by Ilterish Qaghan. In fact, according to one source, the inscriptions contain “rhythmic and parallelistic passages” that resemble that of epics. The inscriptions were discovered by Nikolay Yadrintsev’s expedition in 1889, published by Vasily Radlov. The original text was written in the Old Turkic alphabet and was deciphered by the Danish philologist Vilhelm Thomsen in 1893. Vilhelm Thomsen first published the translation in French in 1899. He then published another interpretation in Danish in 1922 with a more complete translation. Before the Orkhon Inscriptions were deciphered by Vilhelm Thomsen, very little was known about Turkic script. The scripts are the oldest form of a Turkic language to be preserved. When the Orkhon inscriptions were first discovered, it was obvious that they were a runic type of script that had been discovered at other sites, but these versions also had a clear form, similar to an alphabet. When Vilhelm Thomsen deciphered the translation it was a huge stepping stone in understanding old Turkic script. The inscriptions provided much of the foundation for translating other Turkic writings. The scripts follow an alphabetical form, but also appear to have strong influences of rune carvings. The inscriptions are a great example of early signs of nomadic society’s transitions from use of runes to a uniform alphabet, and the Orkhon alphabet is thought to have been derived from or inspired by a non-cursive version of the Sogdian script.

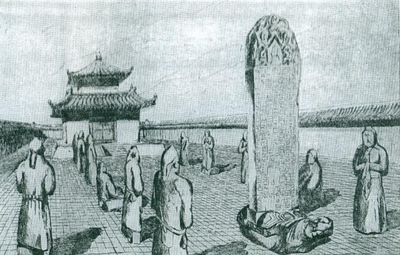

They were erected by the Göktürks in the early 8th century. They commemorate the brothers Bilge Khagan (683-734) and Kul-Tegin (684-731), one a politician and the other a military commander. Both were descendants of Ilterish Qaghan of the Second Turkic Khaganate, which was a prominent Turkic nomadic society during the Tang dynasty. The Göktürks have left artifacts and installations all over their domain, from China to Iran. But only in Mongolia have any memorials to kings and other aristocrats been found. The ones in Khöshöö Tsaidam consist of tablets with inscriptions in Chinese and Old Turkic characters. Both monuments are stone slabs originally erected on carved stone turtles within walled enclosures. Bilge Khagan’s stone shows a carved ibex (the emblem of Göktürk Kagans) and a twisted dragon. In both enclosings, evidence of altars and carved depictions of human couples were found, possibly depicting the respective honorary and his spouse. The Old Turkic inscriptions on these monuments were written by Yollug Tigin who was nephew of Bilge Khagan. These inscriptions together with the Tonyukuk inscription, are the oldest extant attestation of that language. The inscriptions clearly show the sacred importance of the region, as evidenced by the statement, “If you stay in the land of the Ötüken, and send caravans from there, you will have no trouble. If you stay at the Ötüken Mountains, you will live forever dominating the tribes!”. A full English translation of the inscriptions may be found in The Orkhon Inscriptions: Being a Translation of Professor Vilhelm Thomsen’s Final Danish Rendering. TIKA (Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency) showed interest in the site in the late 20th century and finalized their project to restore and protect all three inscriptions. Since 2000, over 70 archeologists from around the world (specifically from Uighur, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Tataristan and Turkey) have studied the area and performed excavations. The site is now protected by fences with buildings for research work and storage of artifacts. The total cost of the project is around 20 million dollars and eventually will include the building of a museum to house the inscriptions and other recently discovered artifacts.

Ordu-Baliq (meaning “city of the court”, “city of the army”), also known as Mubalik and Karabalghasun, was the capital of the first Uyghur Khaganate. It was built on the site of the former Göktürk imperial capital, 27 km north-to-northwest of the later Mongol capital, Karakorum. Its ruins are known as Kharbalgas in Mongolian meaning “black city”. Ordu-Baliq is in a grassy plain called the Talal-khain-dala steppe, on the western bank of the Orkhon River in the Khotont sum of the Arkhangai Province, 16 km northeast of the Khotont village, or 30 km north-to-northwest of Kharkhorin. The Orkhon emerges from the gorges of the Khangai Mountains and flows northward to meet the Tuul River. A favorable micro-climate makes the location ideal for pasturage, and it lies along the most important east-west route across Mongolia. As a result, the Orkhon Valley was a center of habitation and important political and economic activity long before the birth of Genghis Khan who made it known to the wider world. In 744, after the defeat of the last Göktürk Kaghan by the Uyghur-Qarluk-Basmyl alliance, the Uyghurs under Bayanchur Khan (Bayan Çor) established their imperial capital Ordu Baliq on the site of the old ördü (“nomadic capital”). Ordu-Baliq flourished until 840, when it was reduced to ruin by the invading Yenisey Kyrgyzes. The capital occupied at least 32 square kilometers. The ruins of the palace or temple complex laying at coordinates 47.431288°N 102.659349°E — which include the 10-meter-high double clay walls,4 meters apart,14 watch towers, 8 on the Southern side and 6 on the Northern side, two main entrances, one on East side and other on West side, a 12-meter citadel in the southeast corner and a 14-meter-high stupa in the center — clearly indicate that Ordu Baliq or Urgin Balyq ( Old Turkic: 𐰇𐰼𐰏𐰃𐰤𐰉𐰞𐰶 ) was a large, affluent town. The urban area may be divided into three main parts. The central part consisting of numerous buildings surrounded by a continuous wall forms the biggest part. Ruin of a large number of temples and houses are to be found to the south beyond the center. The Khan’s residential palace, which was also ringed by walls on all sides, stood in the northeastern part of the town, where the Russian archaeologist Nikolay Yadrintsev discovered a green granite monument with a statue of a dragon perched at the top and bearing a runic inscription glorifying the khagans. Ordu Baliq was a fully fortified commandry and commercial entrepot typical of the central points along the length of the Silk Road. The well-preserved remains now consist of concentric fortified walls and lookout towers, stables, military and commercial stores, and administrative buildings. There are remains of a water drainage system. Archaeologists established that certain areas were allotted for trade and handcrafts, while in the center of the town were palaces and temples, including a monastery. The palace had fortified walls around it and two main gates, north and south, as well as moats filled with water and watchtowers. The architectural style and planning of the city appear to have close parallels with T’ang Chinese models, although there are elements that appear to have derived inspiration from elsewhere. An ambassador from the Samanid Empire, Tamim ibn Bahr, visited Ordu Baliq in 821 CE and left the only written account of the city. He traveled through uninhabited steppes until arriving in the vicinity of the Uighur capital. He described Ordu-Baliq as a great town, “rich in agriculture and surrounded by rustaqs (villages) full of cultivation lying close together. The town had twelve iron gates of huge size. The town was populous and thickly crowded and had markets and various trades.” He reported that amongst the townspeople, Manichaeism prevailed. The most striking detail of his description is the golden yurt or tent on top of the citadel where the khagan held court.

He says that from (a distance of) five farsakhs before he arrived in the town (of the khaqan) he caught sight of a tent belonging to the king, (made) of gold. (It stands) on the flat top (sath) of his castle and can hold (tasa’) 100 men.

The golden tent was considered the heart of the Uyghur power, gold being the symbol of imperial rule. The presence of a golden tent is confirmed in Chinese historical accounts where the Kirghiz khan was said to have vowed to seize the Uyghurs’ golden tent. In 1871, the Russian traveler Paderin was the first European to visit the ruins of the Uighur capital. Only the wall and a tower were in existence, while the streets and ruins outside the wall could be seen at a distance. He was told that the Mongols call it either Kara Balghasun (“black city”) or khara-kherem (“black wall”). Paderin’s belief that this was the old Mongol capital Karakorum has been shown to be incorrect. The site was identified as a ruined Uyghur capital by the expedition of Nikolay Yadrintsev in 1889 and two expeditions of the Helsingfors Ugro-Finnish society (1890), followed by that of the Russian Academy of Sciences, under Friedrich Wilhelm Radloff (1891).

Karakorum (Khalkha Mongolian: Хархорум, Kharkhorum;Mongolian Script:ᠬᠠᠷᠠᠬᠣᠷᠣᠮ, Karakorum; Chinese: 哈拉和林) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan in the 14–15th centuries. Its ruins lie in the northwestern corner of the Övörkhangai Province, near today’s town of Kharkhorin and adjacent to the Erdene Zuu Monastery, the probable earliest surviving Buddhist monastery in Mongolia. The Orkhon valley was a center of the Xiongnu, Göktürk, and Uyghur empires. To the Göktürks, the nearby Khangai Mountains had been the location of the Ötüken, and the Uyghur capital Karabalgasun was located close to where later Karakorum would be erected (downstream the Orkhon River 27 km north–west from Karakorum). This area is probably also one of the oldest farming areas in Mongolia. In 1218–19, Genghis Khan rallied his troops for the campaign against the Khwarezm Empire in a place called Karakorum, but the actual foundation of a city is usually said to have occurred only in 1220. Until 1235, Karakorum seems to have been little more than a yurt town; only then, after the defeat of the Jin empire, did Genghis’ successor Ögedei erect walls around the place and build a fixed palace. Ögedei Khan gave the decree to build the Tumen Amgalan Ord (Palace of Myriad Peace, Wan’an’gong in Chinese) in 1235 the year after he defeated the Jin Dynasty. It was finished in one year. In the History of Yuan (元史) it is written in the section for Taizong (太宗) Ögedei Khan: “In the seventh year (1236), in the year of the blue sheep the Wanangong (萬安宮) was established in Helin (和林, Karakorum).” One of Genghis Khan’s nine ministers the Khitan Yelü Chucai (1190–1244) said the following poem during the ridge raising ceremony of the Tumen Amgalan Ord: “Installed ridge well fit and stone foundation, The parallel placed majestic palace has been raised, When the bells and drums of the Lord and officials sound pleasantly, The setting sun calls the horses of war to itself from the mountain peaks.” The Mongolian version of the poem is as follows: “Tsogtslon tavih nuruu chuluun tulguur, Zeregtsen zogsoh surleg asriig bosgovoi, Ezen tushmediin honh hengereg ayataihan hanginan duursahad, Echih naran uuliin tolgoigoos dainii agtadiig ugtnam. The name Karakorum or “Kharkhorin” literally translates to ‘black-twenty’. But linguists argue that the ‘khorin’ might have been a diversion of the word ‘khurem’, which means “castle” in Mongolian. Other translations vary.

Under Ögedei and his successors, Karakorum became a major site for world politics. Möngke Khan had the palace enlarged, and the great stupa temple completed. They had the Parisian goldsmith, Guillaume Bouchier, design the Silver Tree of Karakorum for the city center. A large tree sculpted of silver and other precious metals rose up from the middle of the courtyard and loomed over the palace, with the branches of the tree extended into the building. Silver fruit hung from the limbs and it had four golden serpents braided around the trunk, while within the top of the tree was placed a trumpet angel, all as automata performing for the emperor’s pleasure. When the khan wanted to summon the drinks for his guests, the mechanical angel raised the trumpet to his lips and sounded the horn, whereupon the mouths of the serpents began to gush out a fountain of alcoholic beverages into the large silver basin arranged at the base of the tree. William of Rubruck, a Flemish Franciscan missionary and papal envoy to the Mongols reached Karakorum in 1254. He has left one of the most detailed, though not always flattering, accounts of the city. He compared it rather unfavorably to the village of Saint-Denis near Paris, and was of the opinion that the royal abbey there was ten times as magnificent as the Khan’s palace. On the other hand, he also described the town as a very cosmopolitan and religiously tolerant place, and the silver tree he described as part of Möngke Khan’s palace as having become the symbol of Karakorum. He described the walled city as having four gates facing the four directions, two quarters of fixed houses, one for the “Saracenes” and one for the “Cathai”, twelve pagan temples, two mosques, as well as a Nestorian church.

When Kublai Khan claimed the throne of the Mongol Empire in 1260—as did his younger brother, Ariq Böke—he relocated his capital to Shangdu, and later to Khanbaliq (Dadu, today’s Beijing). Karakorum was thence reduced to a mere administrative center of a mere provincial backwater of the Yuan dynasty that was founded in China in 1271. Furthermore, the ensuing Toluid Civil War with Ariq Böke and a later war with Kaidu deeply affected the town. In 1260, Kublai disrupted the town’s grain supply, while in 1277 Kaidu took Karakorum, only to be ousted by Yuan troops and Bayan of the Baarin in the following year. In 1298–99 prince Ulus Buqa looted its markets and the grain storehouses. However, the first half of the 14th century proved to be a second era of prosperity: in 1299, the town had been expanded eastwards, then in 1311, and again from 1342 to 1346, the stupa temples were renewed. After the collapse of the Yuan dynasty in 1368, Karakorum became the residence of Biligtü Khan in 1370. In 1388, Ming troops occupied and later razed the capital. According to Saghang Sechen’s Erdeni-yin Tobči, in 1415 a khuriltai decided to rebuild it, but no archaeological evidence for such a venture has been found yet. However, Karakorum was inhabited at the beginning of the 16th century, when Batu-Möngke Dayan Khan made it a capital once again. In the following years, the town changed hands between Oirads and Chinggisids several times, and was consequently given up permanently.

The Erdene Zuu Monastery stands near Karakorum. Various construction materials were taken from the ruin to build this monastery. The actual location of Karakorum was long unclear. First hints that Karakorum was located at Erdene Zuu were already known in the 18th century, but until the 20th century there was a dispute whether or not the ruins of Karabalgasun, or Ordu-Baliq, were in fact those of Karakorum. In 1889, the site was conclusively identified as the former Mongol capital by Nikolai Yadrintsev, who discovered examples of the Orkhon script during the same expedition. Yadrintsev’s conclusions were confirmed by Wilhelm Radloff. Dening Hall of the Beiyue Temple built in 1270 during the Yuan Dynasty closely resembles the lost palace architecture of Dadu (Beijing) and Karakorum. The first excavations took place in 1933–34 under D. Bukinich. After his Soviet-Mongolian excavations of 1948–49, Sergei Kiselyov concluded that he had found the remains of Ögödei’s palace. However, this conclusion has been put into doubt by the findings of the 2000–2004 German-Mongolian excavations, which seem to identify them as belonging to the great stupa temple rather than to Ögödei’s palace. Excavation findings include paved roads, some brick and many adobe buildings, floor heating systems, bed-stoves, evidence for the processing of copper, gold, silver, iron (including iron wheel naves), glass, jewels, bones, and birch bark, as well as ceramics and coins from China and Central Asia. Four kilns have also been unearthed. In 2004, then Prime Minister Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj appointed a working group of professionals to develop a project to build a new city at the site of the ancient capital Karakorum. According to him, the new Karakorum was to be designed to be an exemplary city, with a vision of its becoming the capital of Mongolia. After his resignation and the appointment of Miyeegombyn Enkhbold as prime minister, the project was abandoned.

The Erdene Zuu Monastery (Mongolian: Эрдэнэ Зуу хийд, Chinese:光顯寺, Tibetan:ལྷུན་གྲུབ་བདེ་ཆེན་གླིང་) is probably the earliest surviving Buddhist monastery. Located in Övörkhangai Province, approximately 2 km north-east from the center of Kharkhorin and adjacent to the ancient city of Karakorum. The monastery is affiliated with the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Abtai Sain Khan, ruler of the Khalkha Mongols and grandfather of Zanabazar, the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu, ordered construction of the Erdene Zuu monastery in 1585 after his meeting with the 3rd Dalai Lama and the declaration of Tibetan Buddhism as the state religion of Mongolia. Stones from the nearby ruins of the ancient Mongol capital of Karakorum were used in its construction. Planners attempted to create a surrounding wall that resembled a Tibetan Buddhist rosary featuring 108 stupas (108 being a sacred number in Buddhism), but this objective was probably never achieved. The monastery’s temple walls were painted, and the Chinese-style roof covered with green tiles. The monastery was damaged in 1688 during one of the many wars between Dzungars and Khalkha Mongols. Locals dismantled the wooden fortifications of the abandoned monastery. It was rebuilt in the 18th century and by 1872 had a full 62 temples and housed up to 1000 monks. According to tradition, in 1745 a local Buddhist disciple named Bunia made several unsuccessful attempts to fly with a device he invented similar to parachute. In 1939 the Communist leader Khorloogiin Choibalsan ordered the monastery destroyed, as part of a purge that obliterated hundreds of monasteries in Mongolia and killed over ten thousand monks. Three small temples and the external wall with the stupas survived the initial onslaught and by 1944 Joseph Stalin pressured Choibalsan to maintain the monastery (along with Gandantegchinlen Monastery in Ulaanbaatar) as a showpiece for international visitors, such as U.S. Vice President Henry Wallace, to prove that the communist regime allowed freedom of religion. In 1947 the temples were converted into museums and for the four decades that followed Gandantegchinlen Khiid Monastery became Mongolia’s only functioning monastery. After the fall of Communism in Mongolia in 1990, the monastery was turned over to the lamas and Erdene Zuu again became a place of worship. Today Erdene Zuu remains an active Buddhist monastery as well as a museum that is open to tourists. On a hill outside the monastery sits a stone phallus called Kharkhorin Rock. The phallus is said to restrain the sexual impulses of the monks and ensure their good behavior.

Tövkhön Monastery (Mongolian: Төвхөн хийд, Töwhön híd), one of Mongolia’s oldest Buddhist monasteries, is located on the border of Övörkhangai Province and Arkhangai Province in central Mongolia, approximately 47 kilometers southwest of Kharkhorin. Tövkhön Monastery was first established in 1648 by the 14-year-old Zanabazar, the first Jebtsundamba Khutuktu and spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism for the Khalkha in Outer Mongolia. He determined that the location on the Shireet Ulaan Uul mountain overlooking a hill at 2,600 meters above sea-level was an auspicious location. The first physical structures were built upon his return from studying in Tibet in 1653. Zanabazar, who was a gifted sculptor, painter, and musician, used the monastery, originally called Bayasgalant Aglag Oron (Happy Secluded Place), as his personal retreat over the course of 30 years. While there created many of his most famous works. It was also where he developed the soyombo script. The monastery was destroyed in 1688 by Oirat Mongols during their military campaign against Eastern Khalkha Mongols. Restored in 1773, the monastery suffered severe damage during the Stalinist purges of the late 1930s as Mongolia’s communist regime sought to destroy the Buddhist religion in the country. Religious activities at the monastery restarted in 1992 and restoration of the monastery’s grounds was completed in 1997. Two original temples and two stupas from the 17th century still stand, along with additional temples built in the 18th century. Ceremonies were staged to re-consecrate the monastery and a new statue of Gombo Makhagal (Mahakala). Several monks now reside and practice at the monastery full-time. Remains of the 13th and 14th century Mongol palace at Doit Hill, thought to be Ögedei Khan’s residence and The Ulaan Tsutgalan waterfall, a waterfall, ten meters wide and twenty meters high, that can sometimes go dry or even freeze during winter are the other sites in the valley.

The Orkhon Valley clearly demonstrates how a strong and persistent nomadic culture, led to the development of extensive trade networks and the creation of large administrative, commercial, military and religious centers. The empires that these urban centers supported undoubtedly influenced societies across Asia and into Europe and in turn absorbed influence from both east and west in a true interchange of human values. Underpinning all the development within the Orkhon valley for the past two millennia has been a strong culture of nomadic pastoralism. This culture is still a revered and indeed central part of Mongolian society and is highly respected as a ‘noble’ way to live in harmony with the landscape. The Orkhon Valley is an outstanding example of a valley that illustrates several significant stages in human history. First and foremost it was the centre of the Mongolian Empire; secondly it reflects a particular Mongolian variation of Turkish power; thirdly, the Erdene Zuu monastery and the Tuvkhun hermitage monastery were the setting for the development of a Mongolian form of Buddhism; and fourthly, Khar Balgas, reflects the Uighur urban culture in the capital of the Uighur Empire. All elements necessary to express the Outstanding Universal Value of the property of Orkhon Valley Cultural Landscape are included within the boundaries of the inscribed area. The ecology of overall landscape and pastoral practices are vulnerable to lowering water table, associated with tree-cutting and mining, pollution of watercourses and the effects of over-grazing. The visual integrity of the landscape is vulnerable to modern roads, tracks and power lines. Lack of maintenance of monastery buildings, city walls and Turkic graves could impact on integrity.

Overall, the Orkhon Valley retains a high level of authenticity as a continuing cultural landscape, reflecting the long-standing traditions of Central Asian nomadic pastoralism. The basic use of the land has remained consistent over the centuries and has not adversely affected the component archaeological features of the landscape, the authenticity of which remains high individually and collectively. Although some modern features have obtruded into the landscape, the way in which the landscape is used is still essentially traditionally nomadic, with herdsmen moving their flocks across it in season transhumance. The pastoral management regime of the grasslands and the continuing intangible and tangible traditions associated with the nomadic way of life are integral to the property’s continued authenticity. The central and local authorities recognize how vital it is to sustain pastoralism as means of managing this cultural landscape. According to the Constitution of Mongolia adopted in 1992, each citizen has the right to live in a healthy and safe environment; additionally, lands and natural resources can be subjected to national ownership and state protection. Parliament Resolution No.43 under the Law on Special Protected Areas (1994) declared an area of the Khangai Mountains, including the upper part of OVCL, a State Special Protection Area, establishing Khangai Mountain Park in 1996. The northern part of the OVCL has been given “limited protected status” under the Law on Special Protected Area Buffer Zones passed in 1997. The five primary sites in the Orkhon Valley have been designated as Special Protected Areas and 20 historical and archaeological sites as Protected Monuments.