Featured in this Issue Cover Story Three Transformative Outcomes Achieved with Mentoring Action Research Supporting Student Social and Emotional Learning through RULER Curriculum Purposeful Grade Reporting in the Student-Centered Classroom The EARCOS Triannual JOURNAL A Link to Educational Excellence in East Asia FALL 2022

The ET Journal is a triannual publication of the East Asia Regional Coun cil of Schools (EARCOS), a nonprofit 501(C)3, incorporated in the state of Delaware, USA, with a regional office in Manila, Philippines. Membership in EARCOS is open to elementary and secondary schools in East Asia which offer an educational program using English as the primary language of instruc tion, and to other organizations, institutions, and individuals.

OBJECTIVES AND PURPOSES

* To promote intercultural understanding and international friendship through the activities of member schools.

* To broaden the dimensions of education of all schools involved in the Council in the interest of a total program of education.

* To advance the professional growth and welfare of individuals belonging to the educational staff of member schools.

* To facilitate communication and cooperative action between and among all associated schools.

* To cooperate with other organizations and individuals pursuing the same objectives as the Council.

EARCOS BOARD OF TRUSTEES

Andrew Davies, President (International School Bangkok)

Stephen Cathers, Vice President (International School Suva)

Rami Madani, Treasurer (International School of Kuala Lumpur)

Margaret Alvarez, Past President (Director Emeritus ISS International School, Singapore)

Saburo Kagei (St. Mary’s International School)

Barry Sutherland (American International School Vietnam)

Laurie McLellan (Nanjing International School)

Kevin Baker (American International School Guangzhou)

Elsa H. Donohue (Vientiane International School)

Catriona Moran (Saigon South International School)

Andrew Hoover (ex officio), Office of Overseas Schools REO

EARCOS STAFF

Edward E. Greene, Executive Director

Bill Oldread, Assistant Director

Kristine De Castro, Assistant to the Executive Director

Elaine Repatacodo, ELC Program Coordinator

Giselle Sison, ETC Program Coordinator

Ver Castro, Membership & I.T. Coordinator

Edzel Drilo, Webmaster, Professional Learning Weekend, Sponsorship & Advertising Coordinator

Robert Sonny Viray, Accountant

RJ Macalalad, Accounting Assistant

Rod Catubig Jr., Office Staff

East Asia Regional Council of Schools (EARCOS)

Brentville Subdivision, Barangay Mamplasan, Binan, Laguna, 4024 Philippines

Phone: +63 (02) 8779-5147 Mobile: +63 917 127 6460

THE EARCOS JOURNAL

In this Issue

2 Welcome

Message from the Executive Director

4 Welcome New Heads, Principals, Associates, and Individual Members

8 Global Citizenship Awardees & Community Grant Recipients

Cover Story

Leadership

10 Three Transformative Outcomes Achieved with Mentoring By Michael Iannini

12 Storytelling & Deep Learning

How Stories Can Be Used in Any Discipline By LeeAnne Lavender

14 DEIJ

#NotSemantics By Suhana Singh Madia

16 Portrait of a Graduate

How Does Your Community Define Student Success?

By Susie Boss

18 Curriculum

Implementing UDL in Early Years: My UDL Journey By Pooja Kakkar

20 A Plea for Paideia in International Education

22

By Jared Rock

Purposeful Grade Reporting in the Student-Centered Classroom By Yujiro Fujiwara

24 Top Ten SEL Strategies for the Secondary Teacher

By Ruth Poulsen

26 Instructional Coaching

Building a Thriving Coaching Program: 8 Steps to Success

By Kim Cofino

28 Social and Emotional Needs

Ensuring a Welcoming Learning Environment All Year Long By Lauren Harvey, Rebecca Austin-Castillo, and Carl Brenneman

32 Student Well-being

From Data to Action: One School’s Journey to Meaningful Change By Jon Kleiman & Drew Schrader

34

Action Research

An English-Immersion School’s Experience with Data Wise and its Implications to the Work of Professional Learning Communities

By Maria Domingues & Emily Sherwood

36

40

42

44

Promoting Middle School Multilingual Learners’ Willingness To Communicate in the Classroom By Eunae Kim

Exploring the Impact of 360-Degree Feedback on Teachers’ Professional Learning By Melissa Burnell

The Role of Motivation and Memory in Second Language Acquisition By Leandro Venier

Strategic Choice of Specific Co-teaching Models for Scaffolding the Delivery of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Experiences

By Lisa Boulestreau & Jamie Bacigalupo

48

52

56

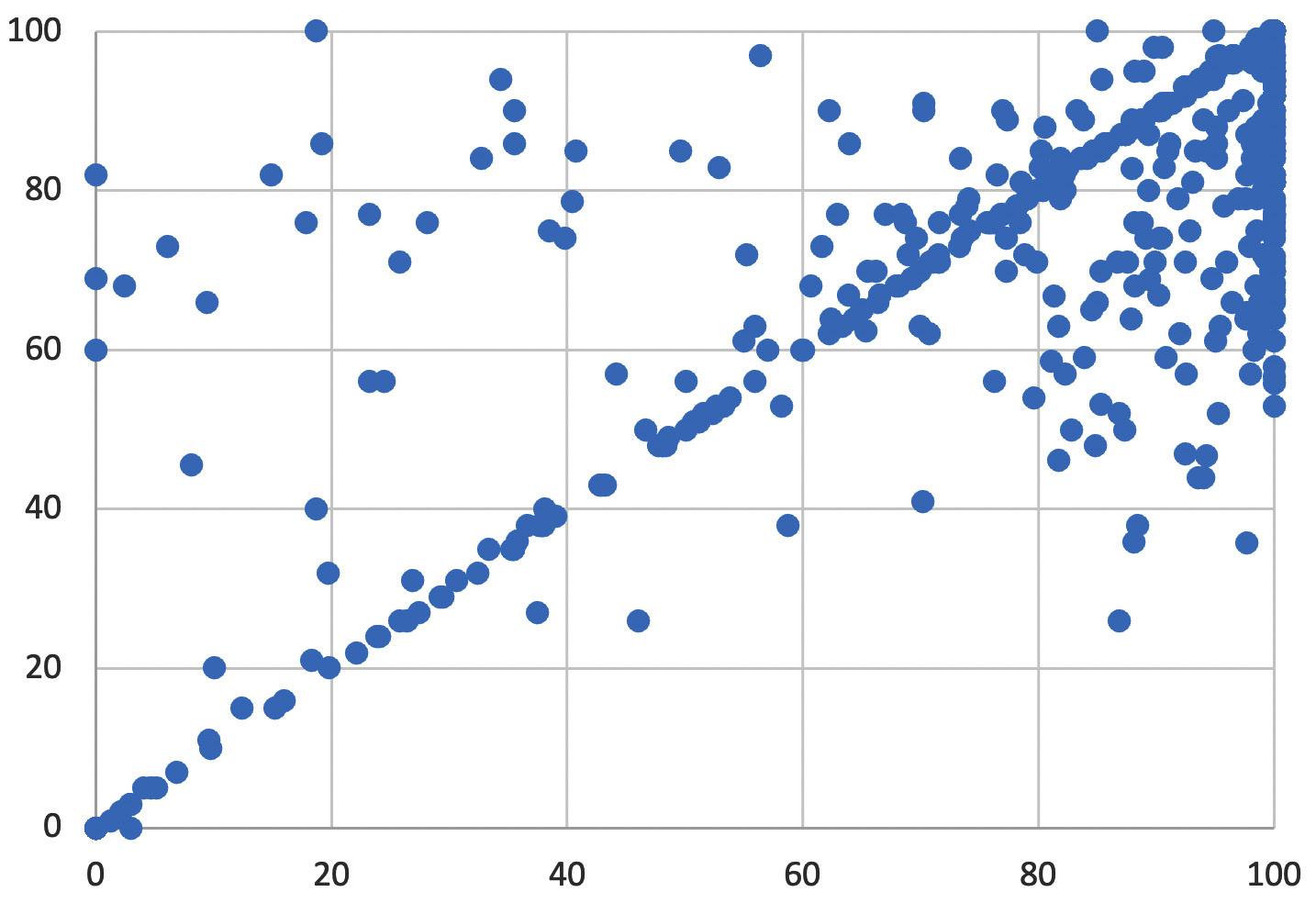

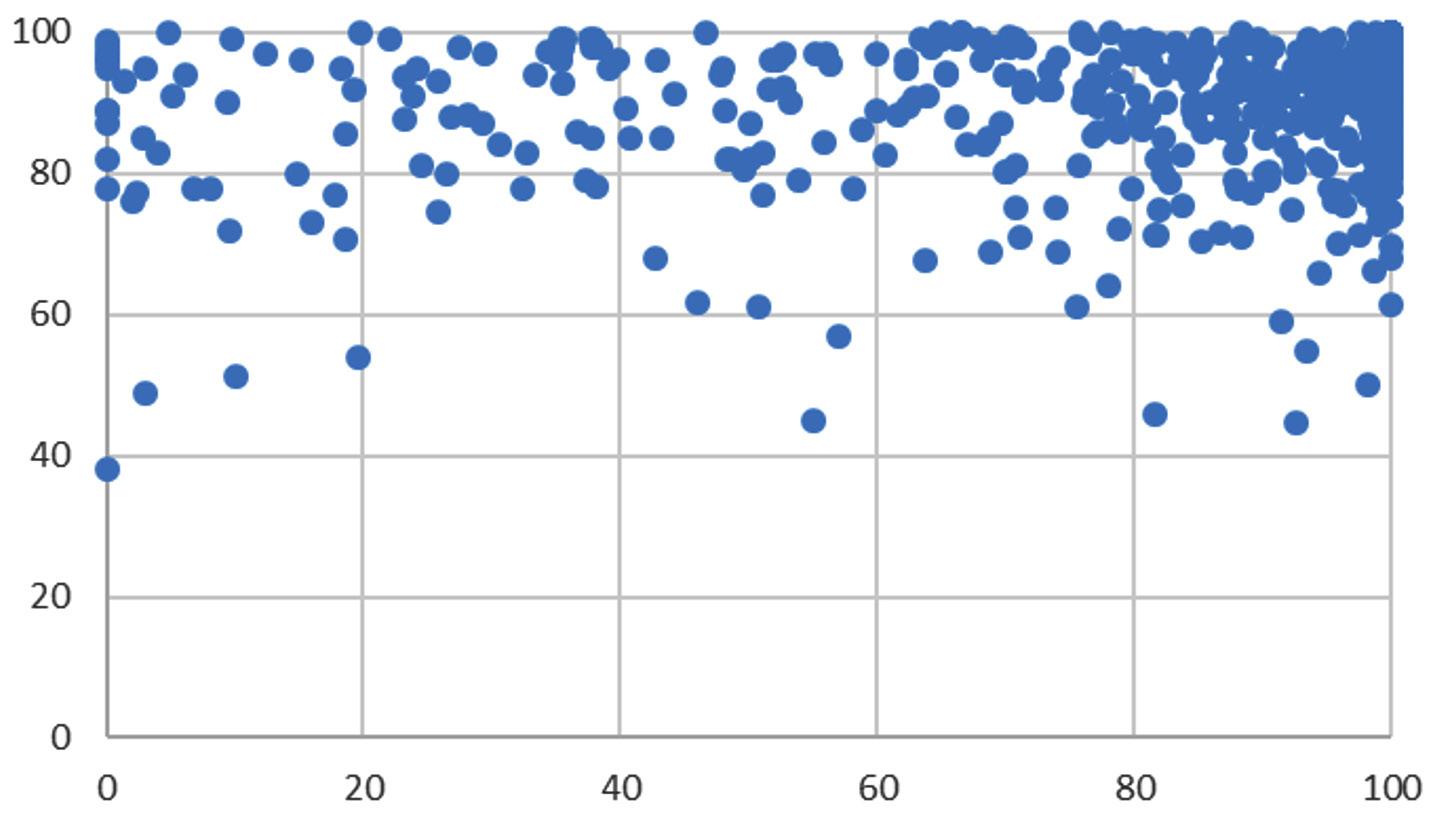

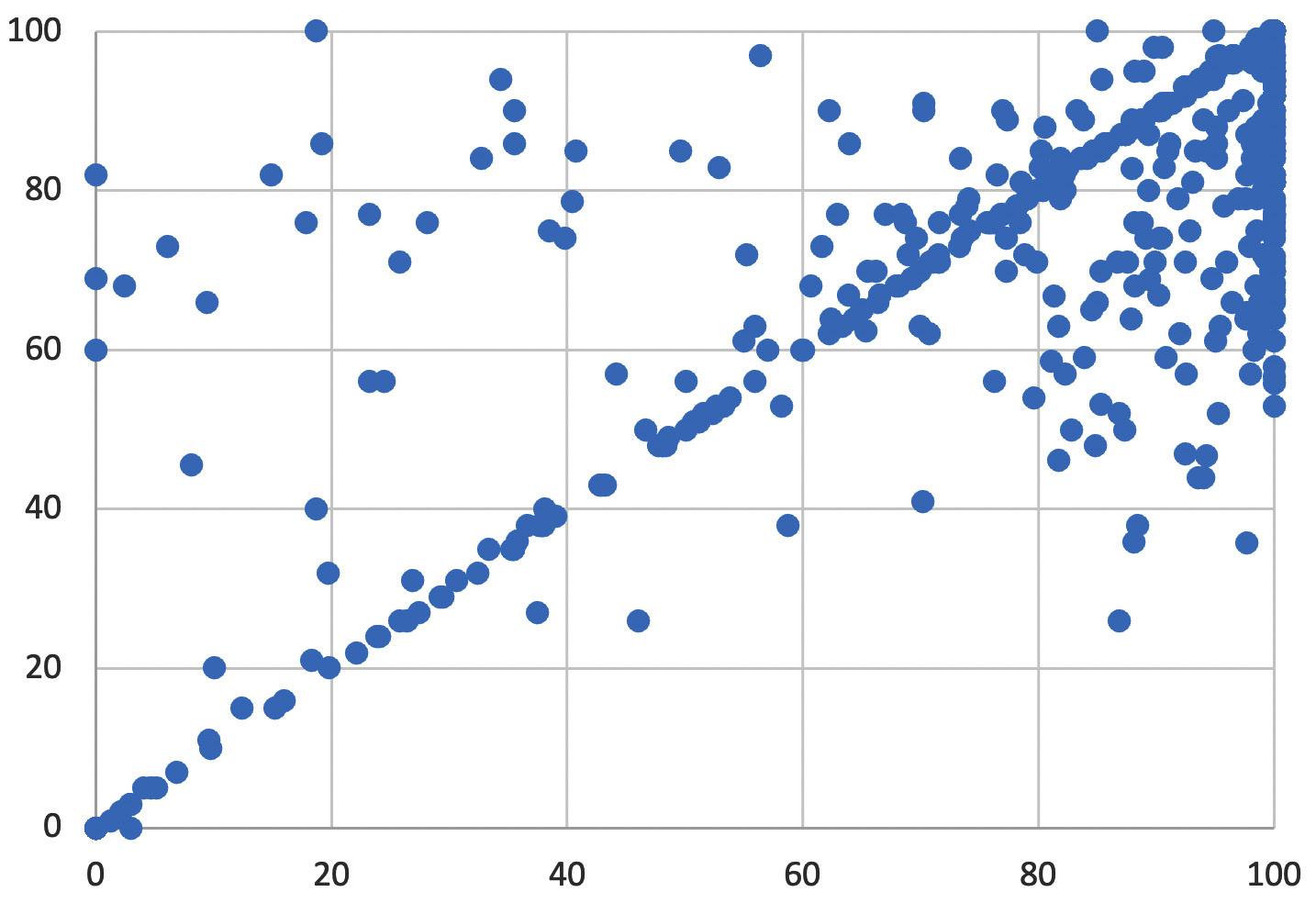

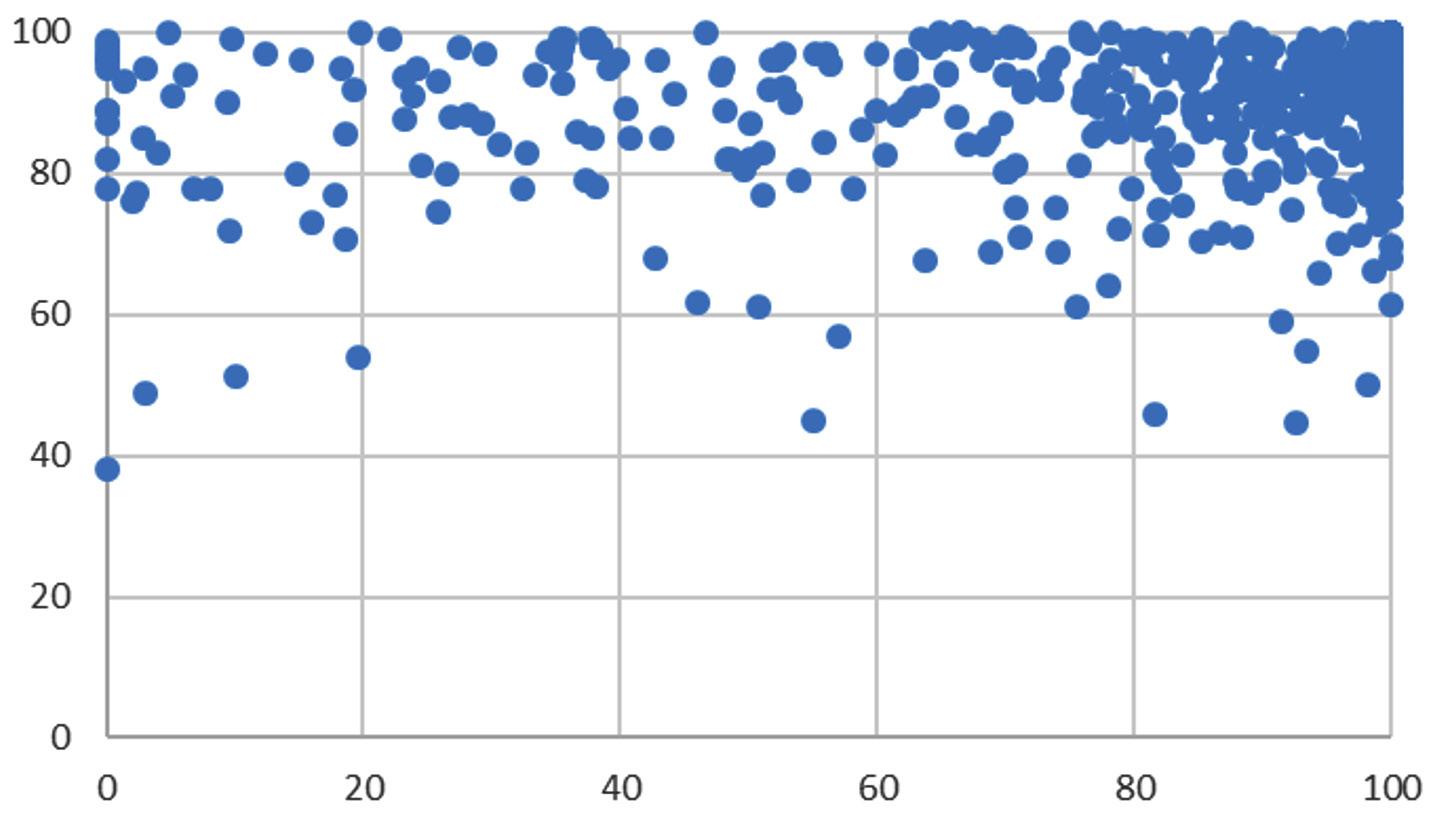

Assessing the Value Added by Online Mathematics Homework By Nathan Warkentin

Supporting Student Social and Emotional Learning through RULER By Brenda Perkins

International Mindedness: Intercultural Appreciation of Physical Beauty By Paolo Euron

Global Citizen Community Service Grant

58

An Artificial Reef Research and Education Project Acquisition By Celicia Cordes

60 Energy Connector By Vansh Kakra

62 One BUK at a Time By Dohyun Kim

64 Enlight the ID By Rindhiya Vishnu Shankar

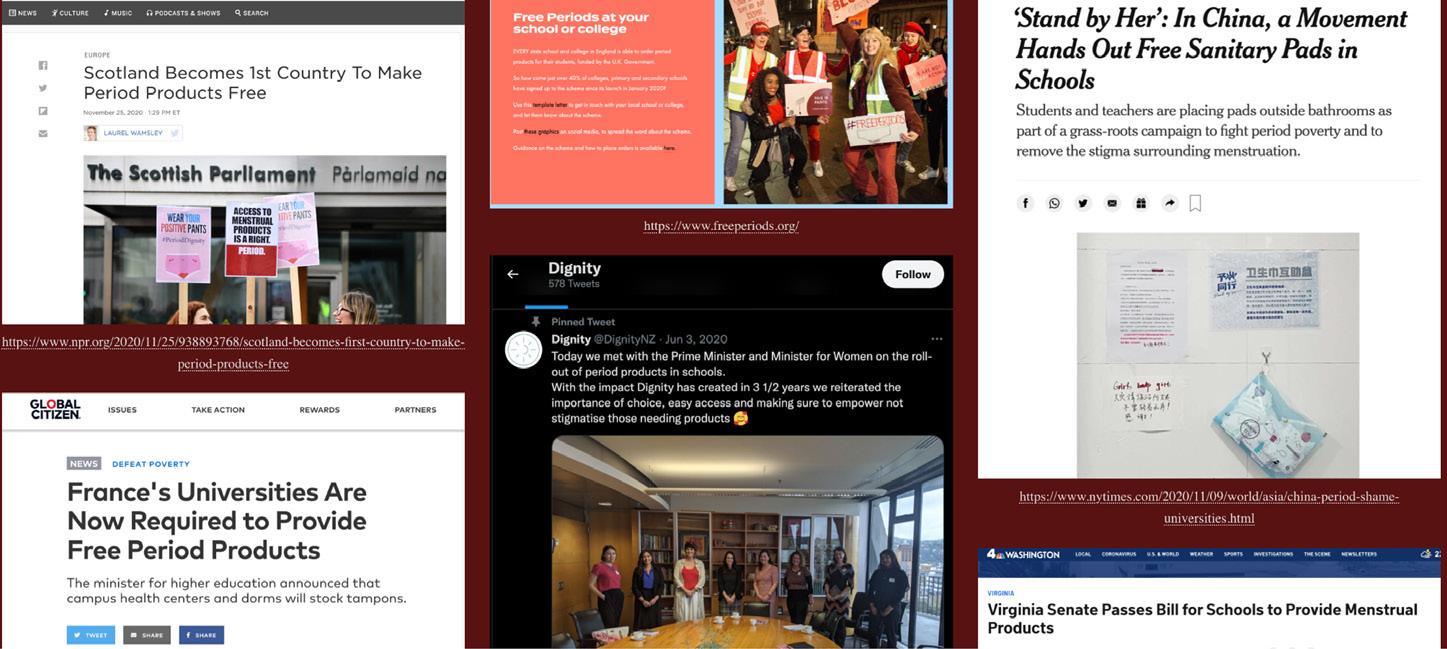

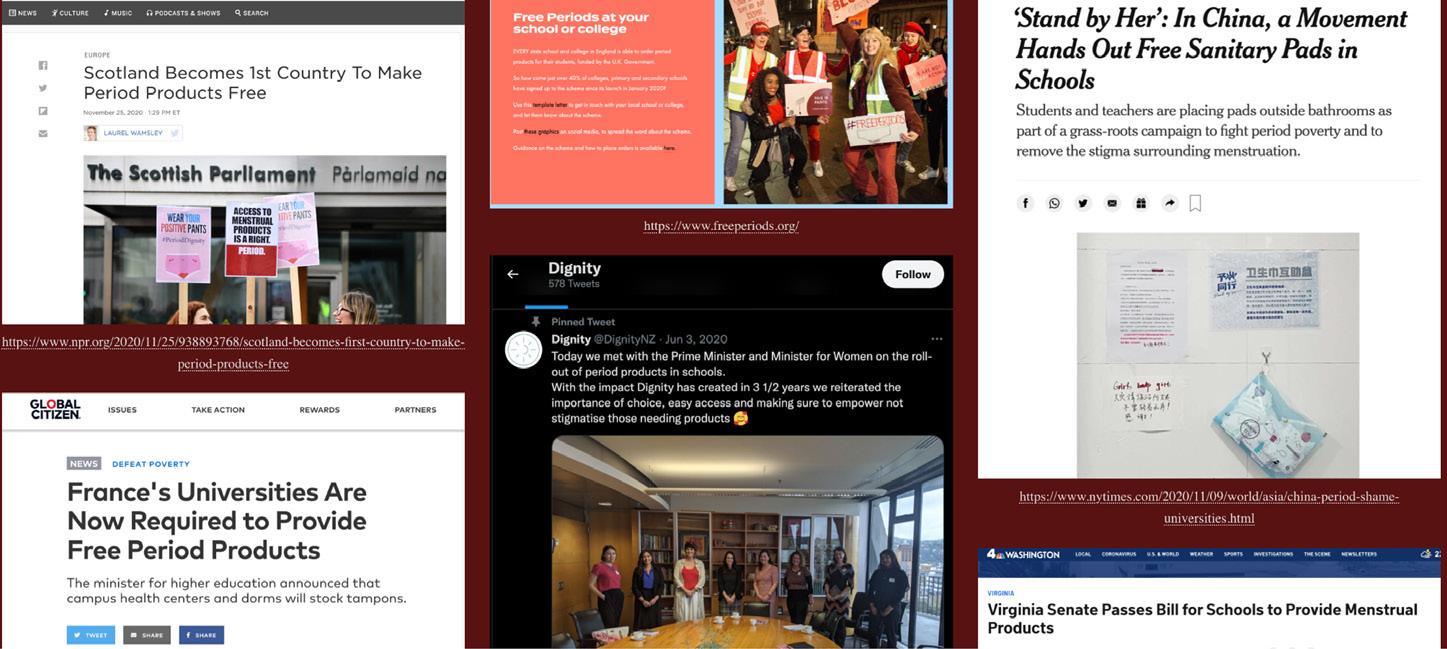

65 Ch4nge the Cycle By Sadie App

66 Light Up Noveleta By Dylan Yap

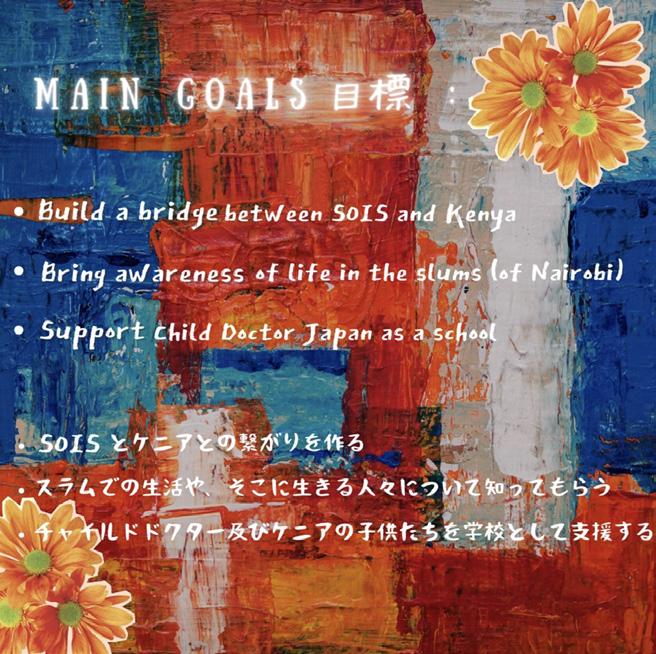

67 Child Doctor Project By Tamami One

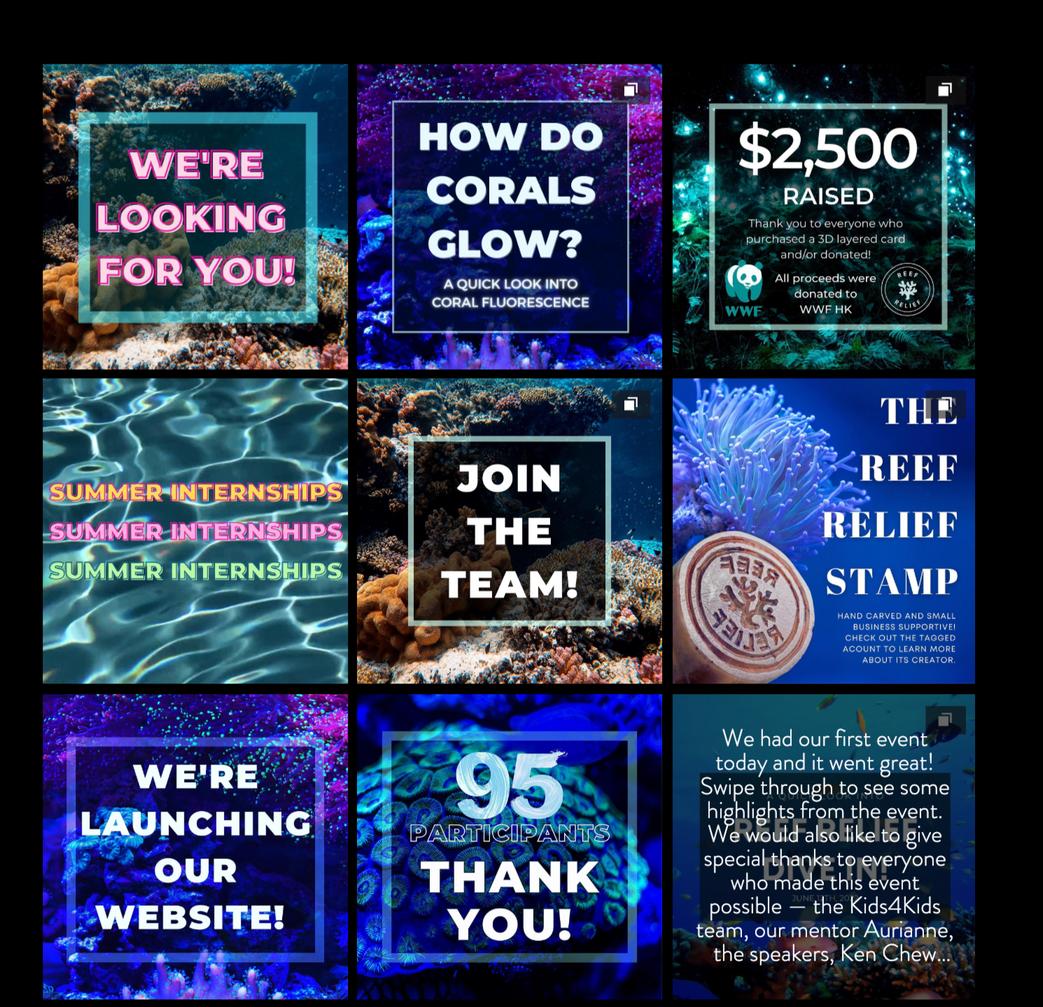

68 Reef Relief By Sabhyata Joshi

69

Service Learning

Promoting Inclusive Environments Within Conservative Cultures By Eli Hisamatsu & Nami Holderman

72

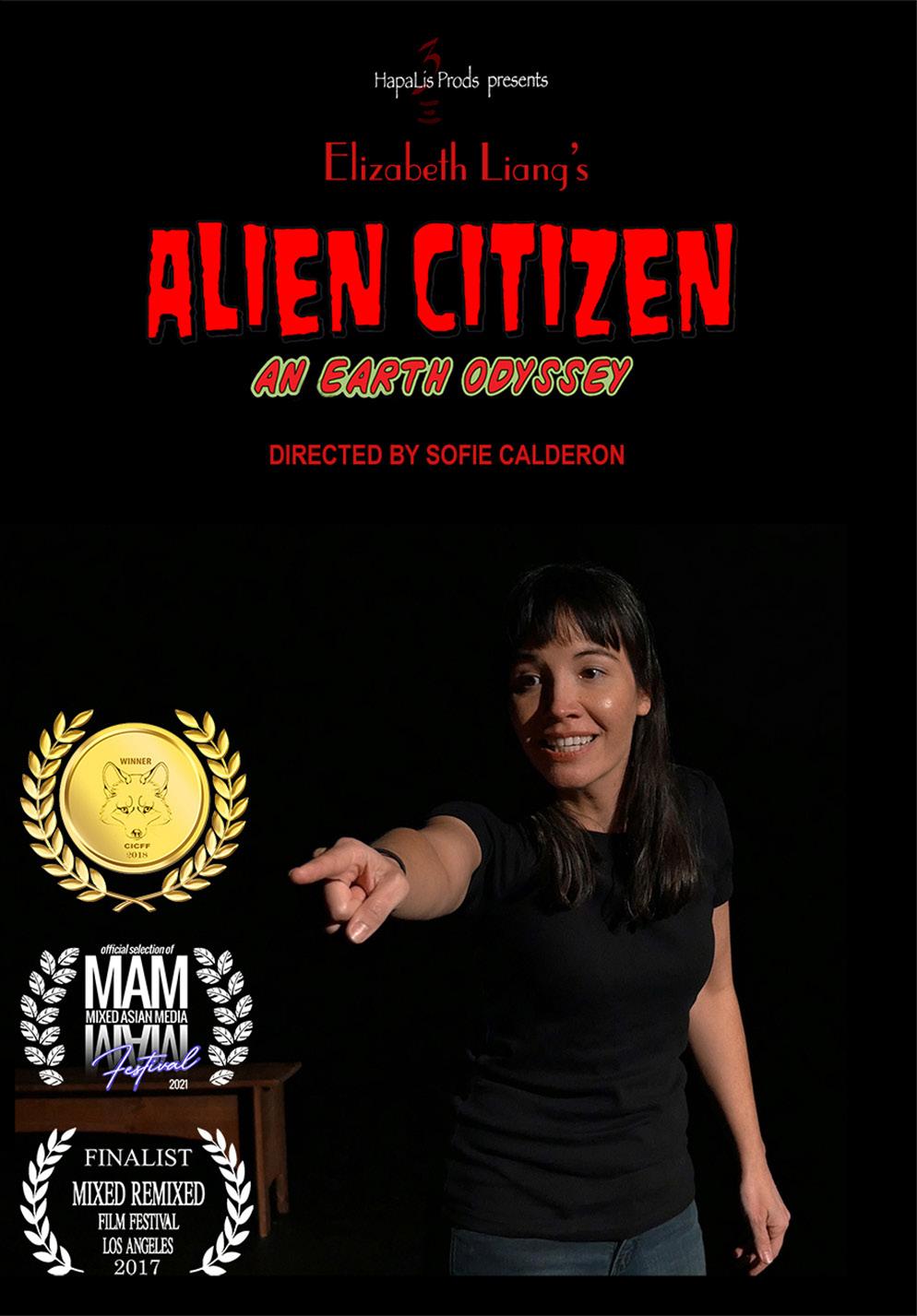

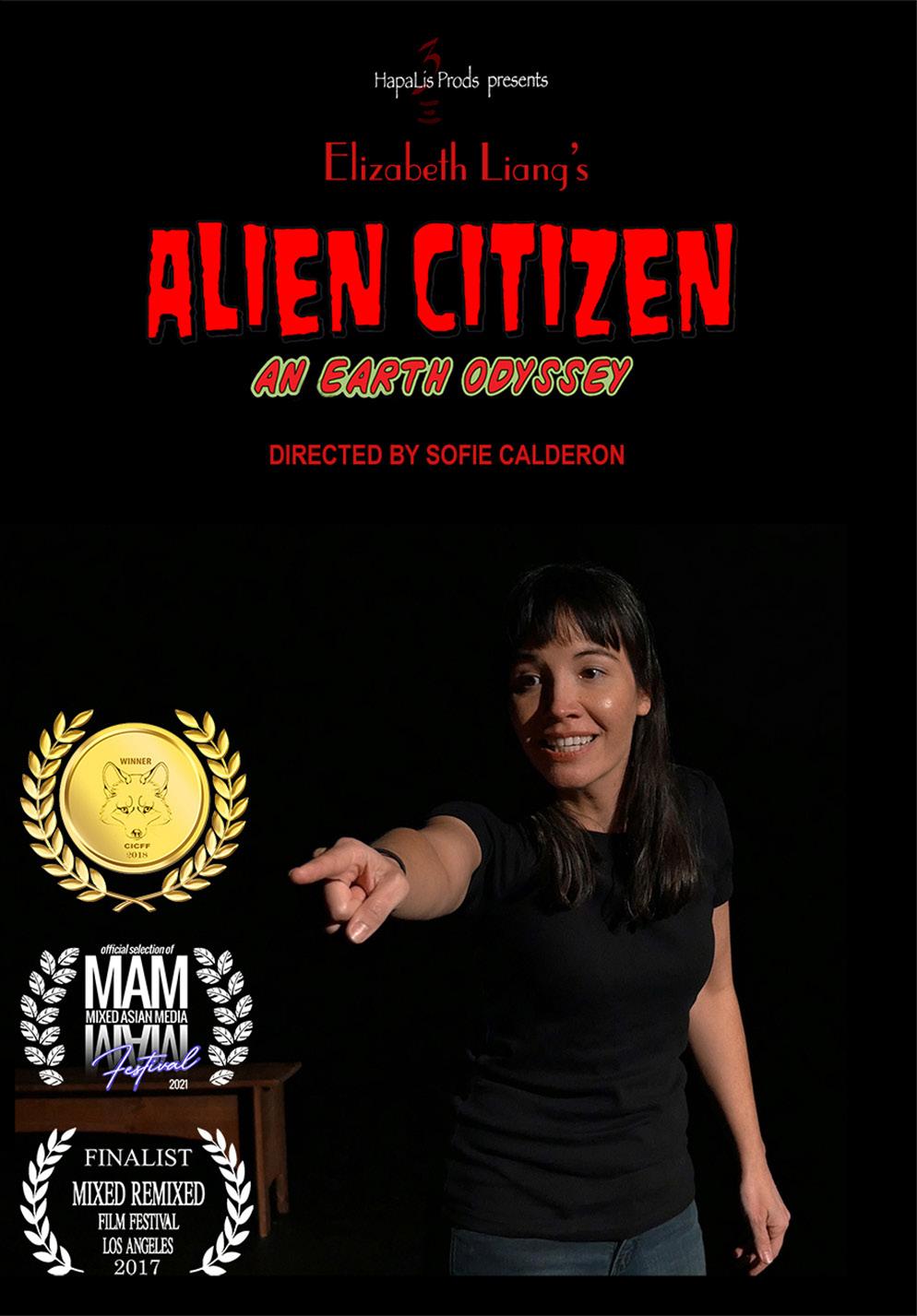

Film Review

Alien Citizen: An Earth Odyssey By Dana Tanu

Elementary Art Gallery (see page 55)

Fall 2022 Issue 1

Message from the Executive Director

It is a pleasure to welcome each of you to this issue of the EARCOS Tri-Annual Journal–as well as to welcome you to what promises to be a more positive and happier year in so many ways across this region. Following nearly three years of unprecedented hard ship for our schools, that proverbial ‘light at the end of tunnel’ is really (and finally) visible for most. The simple fact that most of our schools are open for in-person teaching and learning is cause for celebration. Many have reported that enrollment has begun to inch back closer to pre-pandemic levels. While there is still a bumpy road ahead, the general mood across the region has shifted noticeably toward the positive. Continued patience and resolve, and continued support of one another, will ensure that everyone in the EARCOS region continues to move forward.

Our organization has not had the easiest of times these past three years. Time and again we built Leadership and Teacher Confer ences only to have to cancel them. It has now been three years since we have held the ‘annual’ Leadership Conference and even longer since we had a Teachers’ Conference. Our popular in-person Weekend Workshops disappeared since no one was able to travel. In their stead, we were fortunate to be able to establish a robust webinar program, having offered well over 150 webinars on topics ranging from DEIJ to Leadership to Assessment and UDL, to mental health, imaginative approaches to mathematics, Board Trus teeship, Child Protection and so much more. For so many of us, the webinars became the glue that bound us together through times of worry and isolation and unexpected change. The webinars are now a regular feature of what EARCOS offers our members—so a very positive development in the face of unwelcomed disruption.

The EARCOS Leadership and Mentorship program, headed by Dr. Chris Jansen of the Leadership Lab in Christchurch, New Zealand, continues to serve as a vital forum for scores of school leaders across our region. In a similar vein, for the past two years we have worked closely with the Truman Group, an organization of psychologists who have led small groups of EARCOS school Heads as they confronted leadership and personal challenges from the pandemic. This school year, thanks to a generous grant from the US Office of Overseas Schools, we have been able to create similar Truman cohorts for counselors.

Perhaps the most positive news of the year, for us, is the return of four annual in-person gatherings.

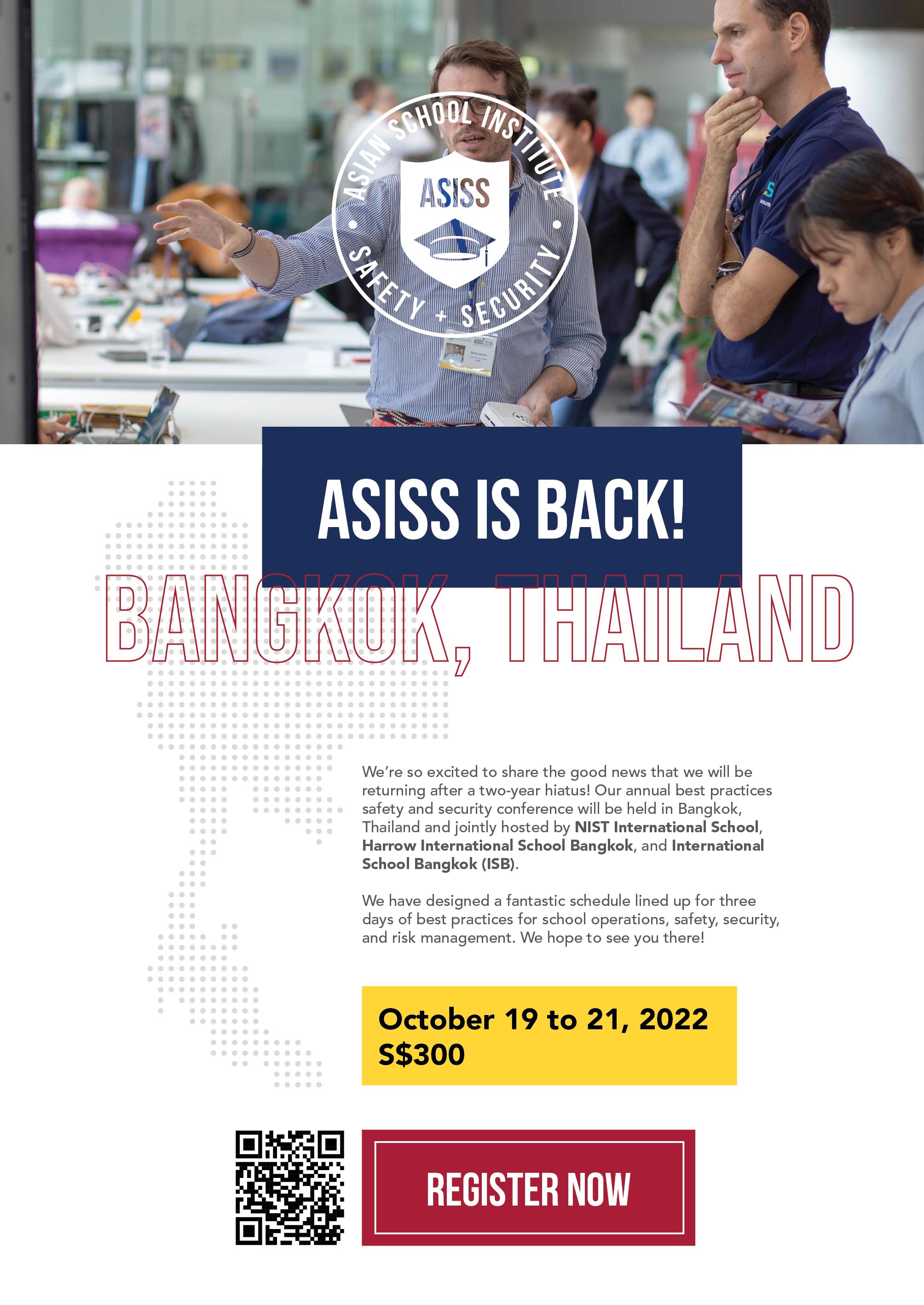

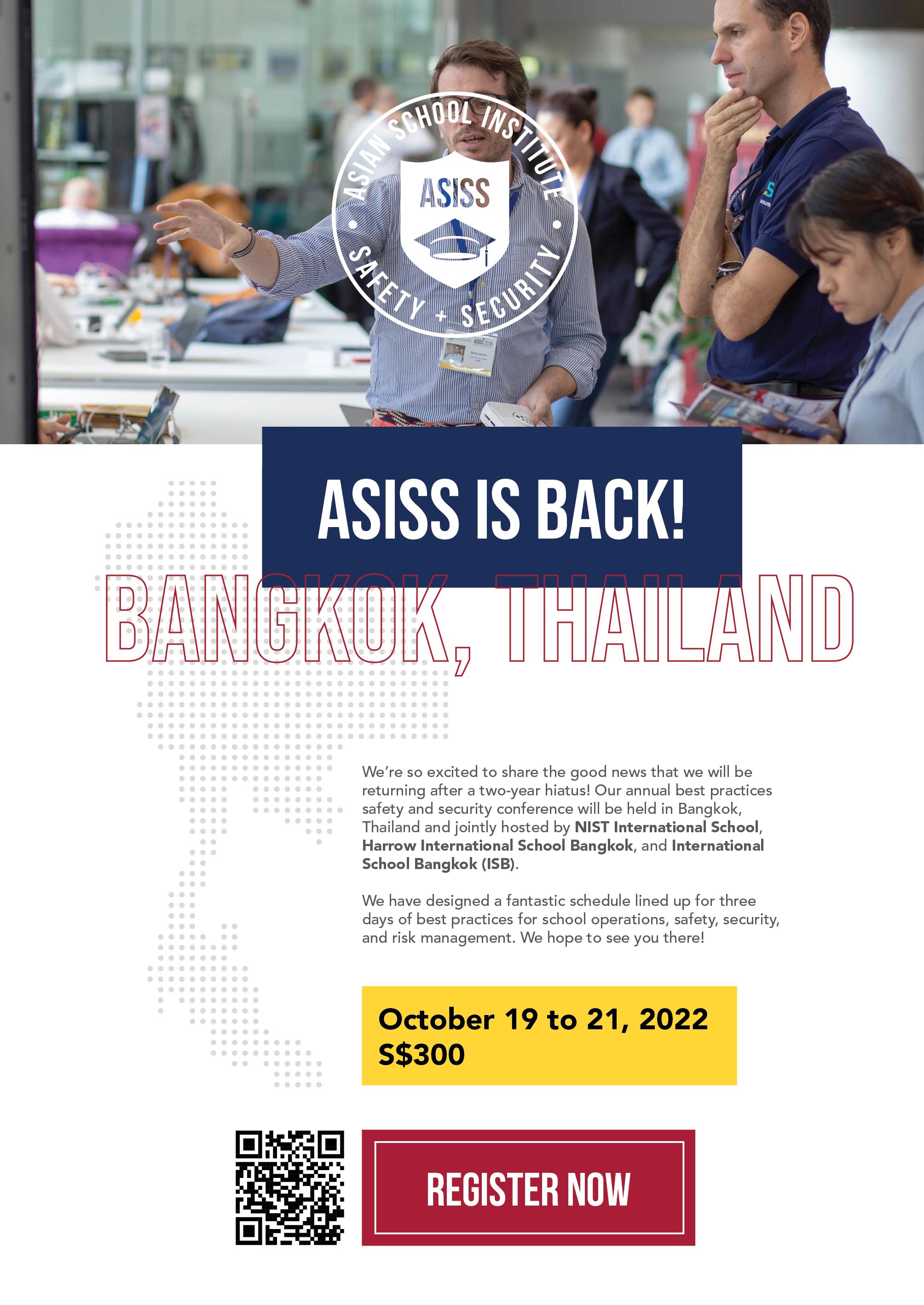

The popular EARCOS-CIS University Admissions Conference will take place in late September in Bangkok with nearly 100 university rep resentatives and nearly 200 counselors. This will be the first time the event has been held since the autumn of 2019.

From October 27-29, the 52nd EARCOS Leadership Conference will be held at the Shangri-La in Bangkok. With a superb set of present ers, this event promises to help us take a giant step forward as we seek ways to increase our collaboration and professional learning and personal support of one another. How incredible will it be to see one another again!

Another shining indicator of improving times is the EARCOS Teachers’ Conference in gorgeous Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia now confirmed from March 23-25, 2023. There is a great line up of speakers and presenters as well as rich opportunities to make or renew connec tions with other international educators from across the region and globe.

And, don’t forget the return of the Annual Heads’ Retreat scheduled for Luang Prabang, Laos from April 28-30, 2023.

Another reason for genuine hope is right in front of you. This issue of ET offers a conference in its own right. It has been inspiring to see the number and variety of manuscripts that have been submitted. The pandemic did nothing to dampen the curiosity and commitment of the region’s educators and students! The Action Research articles, based on awards provided by EARCOS each year, speak volumes about the interests and innovation of so many in our region’s classrooms. And--the articles about the Global Citizens Award-winning Service projects must give you a booster shot of hope. There is so much good going on in the service dimension of our region’s schools. I encourage you to take time to read about these projects—and to consider sharing what your school is doing with service learning in an upcoming issue.

There is so much to be grateful for as we launch the 2022-2023 school year. But it is also true that there are many challenges remain ing. The good news is that no matter where you are and no matter the challenges, EARCOS exists to support you. Please let us know what we might do to support you and your school in your vital work of forging the future.

With best wishes to each of you for the year ahead—and happy reading!

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

Edward E. Greene, Ph.D. Executive Director

2 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Fall 2022 Issue 3 52ND ANNUAL EARCOS LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE 2022 TOGETHER, AGAIN. October 27-29, 2022 Shangri-La, Bangkok Bangkok, Thailand www.earcos.org/elc2022REGISTER NOW!

Welcome New Schools >>

Ascot International School Donnah Ciempka, Head of School www.ascot.ac.th East-West International School Jeffrey Kane, Head of School www.ewiscambodia.edu.kh Oasis International School - Kuala Lumpur Benjamin Hale, Head of School www.ois.edu.my Okinawa Christian School International Megan Roe, Head of School www.ocsi.org Panyaden International School Pran Indhapan, Head of School www.panyaden.ac.th Sekolah Ciputra Martin Blackburn, Head of School www.sekolahciputra.sch.id Stamford American School Hong Kong Karrie Dietz, Head of School www.sais.edu.hk Tokyo West International School Yukiko Kawasaki Kristofferson, Headmistress www.tokyowest.jp XCL World Academy Sean O’Maonaigh, Head of School www.xwa.edu.sg

Welcome New Heads >>

Alice Smith School

Sian May American School Hong Kong Chris Coates Ayeyarwaddy International School Mark Pleasants Bali Island School Michael Miller Bandung Alliance Intercultural School Travis Julian Bangalore International School Geeta Jayanth Branksome Hall Asia Blair Lee Canadian International School of Singapore Allan Weston Canadian International School, Tokyo Kent MacLeod Canggu Community School Ben Voborsky Chiang Mai International School Cherie Kinnersley Christian Academy in Japan David Mawhinney Dalat International School Shawna Wood Dalian American International School Richard Swann Ekamai International School Jarun Damrongkiattiyot Hanoi International School Daun Yorke International School Dhaka Thomas Van Der Wielen International School Eastern Seaboard Roberto Santos International School Manila William Brown International School of Brunei Tony Macfadyen International School of Phnom Penh Eileen Niedermann International School of Qingdao Chris Peek Kaohsiung American School Jim Laney Jr. Keystone Academy Emily McCarren Kyoto International School Myles Jackson

Marist Brothers International School Shawn Hutchinson Medan Independent School Terry Swain Mont’Kiara International School Gary Melton Osaka International School Kurt Mecklem Osaka YMCA International School Dwayne Primeau QSI International School of Shenzhen Claire Berger Seoul International School Jim Gerhard Shanghai American School James Nelligan Kirsta Zavits (Pudong Campus)

Christophe Henry (Puxi Campus)

Shenzhen Shekou International School Harish Kanabar St. Johnsbury Academy - Jeju Corey Johnson Thai-Chinese International School Michael Purser Tohoku International School Kathryn Simms Utahloy Int’l School Guangzhou Dean Croy Sebastien Pelletier (Head of UISZ) Western Int’l School of Shanghai David Edwards Xiamen International School Inna Klein Yantai Huasheng International School Elliot Miller Yew Chung Int’l School of Beijing James Sweeney Yew Chung Int’l School of Qingdao Stephen O’Connor Yew Chung Int’l School of Shanghai Ryan Peet (Puxi)

Cathy Morris (Primary Puxi)

Yogyakarta Independent School Ismail Sumantri

Welcome New High School Principals >>

Access International Academy

Ningbo Glen Porritt American School Hong Kong Amanda Shepherd American School in Taichung Kelly Konicki Ascot International School Mark Allen

Asia Pacific International School Andrew Ris Australian International School Vietnam Ben Armstrong

Ayeyarwaddy International School Kirk Holderman Bali Island School

Michael Miller

Beijing International Bilingual Academy Myles Airelle

Berkeley International School

Jake Varley

Brent International School Manila Todd Wyks

Canadian Int’l School Bangalore Jay Langkamp

4 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Canadian Int’l School of Singapore Daniel Smith

Canggu Community School Max Henson

Chadwick International School Joseph Levno Concordia Int’l School Shanghai Eileen Beckman Dulwich Int’l High School Suzhou Nadir El-Edroos Dwight School Seoul Cameron Forbes Ekamai International School Ronald Mendiola German European School Singapore Claudia Dicken Hangzhou International School Fursey Gotuaco International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Karen Wu International Pioneers School Parminder Kongvattanawong International School Dhaka Chris Boyle International School Eastern Seaboard Joe Hepworth International School Ho Chi Minh City Caleb Nathanael Archer International School Manila David Birchenall International School of Beijing Julie Lemley International School of Busan Gilles Buck International School of Dongguan Ms. Alissa Gouw Int’l School of Nanshan Shenzhen Chelsea Donaldson International School Suva Paulinus Horkan Keystone Academy Regine de Blegiers KIS International School Keegan Combs Korea International School-JeJu Campus Alissa Kordprom Kunming International Academy Jason Chong Mont’Kiara International School Kevin Ritchlin Nansha College Preparatory Academy Sarah MacRoberts Oasis Int’l School - Kuala Lumpur Jessica Hale

Oberoi International School

Subhash Chander Bhatia

Osaka YMCA International School Mark Beales

Panyaden International School Daiju Vithayathil Prem Tinsulanonda International School Shaun Hudson Raffles American School David Hornby Sekolah Ciputra Christopher Allen Seoul International School Gray Macklin Shanghai American School Stephen Caskie Shenzhen Shekou International School Matthew Doige St. Johnsbury Academy - Jeju Justin Boyd Stamford American School Hong Kong Teresa Foard Thai-Chinese International School Kevin Curran

United World College of South East Asia Damian Bacchoo (East) Utahloy Int’l School Guangzhou Fritha Jameson

Victoria Shanghai Academy Shirla Sum Vientiane International School Andrew Ferguson Western Int’l School of Shanghai Evi Singleton XCL World Academy Mark Petterson Xian Hanova International School Aristipo Rodriguez Yantai Huasheng International School Jonathan Van Santen Yew Chung Int’l School of Beijing James Sweeney Yew Chung Int’l School of Chongqing Tim Noblett Yew Chung Int’l School of Qingdao Brendan Bourne Yogyakarta Independent School Ismail Sumantri Yongsan International School of Seoul Jeff Marquis

Welcome New Middle School Principals >>

American School in Taichung Kelly Konicki Asia Pacific International School Judy Park Bali Island School Michael Miller Bangalore International School Anjali Nair Beijing International Bilingual Academy Myles d’Airelle Branksome Hall Asia Patricia Long Concordia Int’l School Shanghai JJ Akin Dalat International School Beverly Stevens Dwight School Seoul Cameron Forbes Ekamai International School Frederick Milton Lee European Int’l School Ho Chi Minh City John Veitch German European School Singapore Sarah Thomas (European Section) Hangzhou International School Fursey Gotuaco

Hanoi International School Mark Schoemer Hong Kong International School Casey Faulknall International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Karen Wu International School Dhaka Chris Boyle International School of Beijing Anne Sweet International School of Busan Gilles Buck Kaohsiung American School Chelsea Armstrong Nansha College Preparatory Academy Hanson Yeung

Nishimachi International School Kalpana Rao Oasis Int’l School - Kuala Lumpur Jessica Hale Oberoi International School Priyadarshini Ramteke Panyaden International School Daiju Vithayathil Punahou School Todd Chow-Hoy Seisen International School Kyoko Sato Seoul International School Michael Gohde Shanghai American School John Ashenden Shenzhen Shekou International School Matthew Doige Singapore American School Chris Beingessner St. Johnsbury Academy - Jeju Eric Beck Thai-Chinese International School Richard Poulin Utahloy Int’l School Guangzhou Fritha Jameson Vientiane International School Andrew Ferguson Western Int’l School of Shanghai Evi Singleton XCL World Academy Mark Petterson Yantai Huasheng International School Jonathan Van Santen Yew Chung Int’l School of Qingdao Brendan Bourne YK Pao School

Ada Wang

Fall 2022 Issue 5

Welcome New Elementary School Principals >>

Access International Academy Ningbo Charity Yi American International School, Vietnam Joe Aldus Ascot International School Laura Rennard Asia Pacific International School

Judy Park Ayeyarwaddy International School Holly Hunt Bali Island School Michael Miller

Bangalore International School Jayati Ashok George Berkeley International School Karen Hendren Canadian International School of Singapore Colleen Drisner Canggu Community School Mike Hopaluk Dulwich College Suzhou Georgina Gray Dwight School Seoul Beth Overby Faith Academy, Inc.

Tara Santos

German European School Singapore Sarah Thomas Global Jaya School Lavesa Devnani Hong Kong International School Ben Hart International Bilingual School of Hsinchu Karen Wu

International Community School - Singapore Samuel Goh International School Dhaka David Longworth International School Eastern Seaboard (ISE) Allison Donohue International School of Beijing Dustin Collins International School of Tianjin Justin Lobsey

Kaohsiung American School

Molly Fitzgerald

KIS International School Chye de Ryckel

Kunming International Academy Jean Bannen Nanjing International School Jacqui Patrick

NIST International School Iain Macfarlane

Oasis International School - Kuala Lumpur Rebecca Unruh

Panyaden International School Erin Michelle Threlfall Punahou School Todd Chow-Hoy

Saigon South International School Melanie Sylvester

Shenzhen Shekou International School Leda Cedo

St. Johnsbury Academy - Jeju Carla Chavez

St. Marys International School

Charles Myers

Stamford American School Hong Kong Rose Chambers

Thai-Chinese International School Scott Dennison

The American School of Bangkok Jenny Sabin

The International School Yangon Sandy Sheppard

Western Academy of Beijing Catherine Pierre Luois

XCL World Academy Edna Lau

Yangon International School Heather Kissack

Yew Chung International School of Beijing Jane Kang

Yew Chung International School of Chongqing Darren May

Welcome Early Childhood Principals >>

Ascot International School Tom Green Bali Island School Michael Miller Canadian International School of Singapore Colleen Drisner Chadwick International School Timothy Tuttle East-West International School Heather Abernathy German European School Singapore Emma Horsey Hong Kong International School Geoff Heney International School Eastern Seaboard Allison Donohue International School of Beijing Dustin Collins Kunming International Academy Jean Bannen NIST International School Iain Macfarlane

Panyaden International School

Erin Michelle Threlfall

QSI International School of Shenzhen Penny Blackwell

Shanghai American School Sharon Townshend Shanghai Community International School Heather Knight Shenzhen Shekou International School Karen Brown-Miller Singapore International School of Bangkok Marion Barbe

TEDA Global Academy Cindy Li

The British School New Delhi Cally Stockwell

XCL World Academy Edna Lau

Yew Chung International School of Beijing Margaret Zhang

Welcome New Individual Members >>

Natalie Chan, Founder

OWN Academy Andrew Gordon, Director LOGOS International School and ASIAN HOPE International School Priscilla Koh, Principal Havil International School Diane Lewthwaite, Head of School Beacon International School Foundation (The Beacon School) Michael Lambert, Head of School True North School

6 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Welcome New Associate Institutions >>

9ine

Technology, Cybersecurity, Privacy

Benchmark Education

English Literary Programs, Early Learning, Inter vention, Leveled Texts

Class Technologies

Edtech

DataClassroom, Inc. Digital lesson content and web application for teaching data skills

DLR Group

Educational Facility Planning / Architectural Design Consulting

Dynatex

Cloud based communications platform for schools to create, manage and distribute content to web mobile and email

Edpuzzle, Inc. Video Learning Platform

Education Perfect Education Technology

Harmony Education Solutions

Curriculum Support, Assessments, STEM Model, Professional Development, American School Model, Consultation, Leadership Development etc.

International School Counselor Association (ISCA)

Provider of professional development services and membership for international school coun selors.

Komodo Student wellbeing software solutions

NOVALEARN LIMITED STEAM Extracurricular Learning Platform

Playground Centre Recreational Facilities Manufacturer and Supplier

Sovereign Group

Financial services - we provide occupational and personal international pensions and savings

Steelcase Office Solutions Ptd Ltd Furniture manufacturer and provider for Office and Learning Envirnoments

TheHagwon.Com

ACT SAT Online Learning Platform

The Jane Group Crisis Communications Consultants

The Safeguarding Company Ltd Safeguarding Services

TheKnowledge-Lab Pte. Ltd. Education technology

William & Mary School of Education University

eiw architects | eiwarch.com.au learning space design Vientiane International School building ideas Fall 2022 Issue 7

Global Citizenship Awardees >>

List of Global Citizenship Award 2022Winners

This award is presented to a student who embraces the qualities of a global citizen. This student is a proud representative of his/her nation while respectful of the diversity of other nations, has an open mind, is well informed, aware and empathetic, concerned and caring for others encouraging a sense of community, and strongly committed to engagement and action to make the world a better place. Finally, this student is able to interact and communicate effectively with people from all walks of life while having a sense of collective responsibility for all who inhabit the globe.

Access International Academy Ningbo Yanbing Hu American Int’l School Hong Kong Sabhyata Joshi American Int’l School of Guangzhou Wei Ying Gwynnie Guo American Pacific International School Kayin (Bonnie) Lau American School Hong Kong Himani Vasnani American School in Taichung Lydia Chen American School of Bangkok, The Sein Sandar Tun Ayeyarwaddy International School Ahkar Min Thant Bali Island School Manon Pecquery Bandung Alliance Intercultural School Angel Gunaman Bandung Independent School Rose Ashworth Bangkok Patana School Rie Aiyama Beijing City International School Yutong Ren Berkeley International School Celicia Cordes Brent International School Baguio Cassey Denise Cunanan Brent International School Manila Katyann Baldwin Brent International School Subic Yuan Wang Busan Foreign School Brian Choi Canadian Academy Manori Koto Canadian Int’l School of Hong Kong Yoyo Yeuk Sze Pang Canadian Int’l School of Singapore Arishya Jindal Cebu International School So Yi (Selly) Park Chadwick International School Yujin (Eugene) Lee Chatsworth International School Minami Mochizuki Christian Academy in Japan Shun Tanaka Concordia International School Hanoi Yu Hyeon Kim Concordian International School Anna Binabdullah Daegu International School Ricky Junyoung Jang Dalat International School Benjamin Wong Dalian American International School Raymond Bian Dominican International School Jason Chun Yu Shih Dwight School Seoul Curie Lee Fukuoka International School Junze Lyu Garden Int’l School Kuala Lumpur John Ling Hangzhou International School Flora Moon Hong Kong International School Yoonjung Choi Hsinchu International School Pei Pei Kuo IGB International School Rindhiya Vishnu Shankar Int’l Christian School - Hong Kong Hiu Ching Ma Int’l Community School - Singapore Josette Hwang International School Bangkok Sutikarn (Aeoi) Thamthiwat International School Dhaka Mursalina Munir

International School Eastern Seaboard Soo Yeon Lim International School Ho Chi Minh City Ha Pham International School Manila Dylan Patrick Ng Yap International School of Beijing Annarosa Li Yee Lam International School of Busan Phillip Pibernat-Park International School of Dongguan Michael Chen International School of Kuala Lumpur Lamija Mrndic Int’l School of Nanshan Shenzhen YaLin Jiang International School of Phnom Penh Kunvecheada Blain International School of Ulaanbaatar Oyundari Gansukh International School Suva Zubeyda Dadasheva K. International School Tokyo Sara Ashida Kaohsiung American School Anne (Ling-Yi) Wu Korea International School-JeJu Campus Yoonseo (Bennie) Ko Korea Kent Foreign School Angelina Koh Kunming International Academy Gabriel Seksig Lanna International School Thailand Min Yoo Marist Brothers International School Joshua Whitney Mont’Kiara International School Taekyoung Kim Nagoya International School Rinka Lee Nanjing International School Yutong Wang Nansha College Preparatory Academy Chenxin Gao NIST International School Rei Tangkijngamwong North Jakarta Intercultural School Abigail Wu Oberoi International School Vansh Kakra Osaka International School Tamami Ono Osaka YMCA International School Sehyeon Kim Prem Tinsulanonda International School Chenxun Zhang Renaissance International School Chi Tran Kim Ruamrudee International School Manyasiri (Pear) Chotbunwong Saigon South International School Phuong-Anh Do Saint Maur International School Isheeka Prabhu Seisen International School Zarah Mathew Sekolah Ciputra Wenny Wibisono Seoul Foreign School Grace An Seoul International School Alice Hyoeun Lee Shanghai American School Nathan Chan Shanghai American School-Puxi Campus Sejin Oh Shanghai Community Int’l School Huai-Yin (Ingrid) Yao Shanghai Community Int’l SchoolPudong Campus Vaishvi Shah Shen Wai International School Ya Qing Su

8 EARCOS Triannual Journal

Singapore American School

Renee Paris Dan Xinh Phan

Singapore Int’l School of Bangkok Natthanun Tonprasert St. Marys International School Roy Igwe

Surabaya Intercultural School Shafira Novianti Adi Dwi Putri Taejon Christian International School Dohyun (Jennifer) Kim TEDA Global Academy Sharon Russel

The American School in Japan Moeka Sugiyama The British School New Delhi Tara Bhattacharya The Harbour School Arial Brookhart

The International School Yangon Rose Zin Tianjin International School MinAh Park Tohoku International School Michael Yamaguchi United Nations Int’l School of Hanoi Carmen Cortizas UWC Thailand International School Alyx Mastor Vientiane International School Diogo Godoi Wells Int’l School - On Nut Campus Shaina Paryani Western Academy of Beijing Yufei (Sophie) Yi Western Int’l School of Shanghai Juhwan Han Wuhan Yangtze International School Jean Iris Deguilmo Lauron Yangon International School Tenzin Gyeltshen Wangyel Yantai Huasheng International School SuJin (Angela) Kim Yew Chung Int’l School of Chongqing Cherry Pan Yew Chung Int’l School ShanghaiPudong campus Zeke McDaniels Yongsan International School of Seoul Priscilla Kang

Global Citizenship Community Grant Recipients >>

All of us here at EARCOS wish to extend our sincere congratulations to the following Global Citizens who have been chosen to receive an EARCOS Global Citizen Community Service Grant of $500 to further their excellent community work during this upcoming aca demic year. The recipients are:

NAME SCHOOL

PROJECT NAME

Rose Ashworth Bandung Independent School Rumah Ruth Nathan Chan Shanghai American School Law Association for Crimes Across History (LACAH) Yoonjung Choi Hong Kong International School For Girls Celicia Cordes Berkeley International School

ATMEC: An Artificial Reef Research and Education Project Angel Gunaman Bandung Alliance Intercultural School Made to Change Sabhayata Joshi American International School Hong Kong Reef Relief Vansh Kakra Oberoi International School

Energy Connector Sadie Kapp KIS International School ch4nge the cycle Dohyun (Jennifer) Kim Taejon Christian International School BUK Time for South Sudan Curie Lee Dwight School Seoul El Salvador Coffee Project Alyx Mastor UWC Thailand International School Plastic Free Phuket Tamami Ono Osaka International School Child Doctor Rindhiya Vishnu Shankar IGB International School

Enlight the ID (Intellectual Disability) and Shine Light on Mental Health Ahkar Min Thant Ayeyarwaddy International School Go Green Yuan Wang Brent International School Subic Shining Through Service Dylan Yap International School Manila Light Up Noveleta

Fall 2022 Issue 9

Three Transformative Outcomes Achieved with Mentoring

A leader’s most important responsibility is to develop leaders.

By Michael Iannini Council of International Schools Affiliated Consultant ACAMIS PD Consultant and Leadership Facilitator

70-20-10, this is the golden rule for successfully develop ing leaders. We know from research that senior leaders are the most proven and powerful tool for empowering aspiring leaders to be accountable for 70% of their own develop ment. Aspiring leaders realize 70% of their leadership de velopment by accepting responsibility for challenging tasks, such as:

• Starting something from nothing,

• Fixing something broken, and

• Being responsible for influencing others without author ity.

However, to ensure aspiring leaders develop from these challenges, which may include failure, senior leaders need to accept 20% of the responsibility for an aspiring leader’s development. This requires senior leaders to regularly in teract with aspiring leaders, in the capacity of a mentor, to clarify roles and expectations, keep them focused on the bigger picture and help them to reflect and learn from their experiences. The role of the mentor is a distinctly different relationship than what might be assumed under a typical ap praiser or manager interaction, even if the persons involved are the same.

10% of any leader’s development is related to structured learning activities, such as workshops, book studies, profes sional reading, and conferences. Structured learning activi ties, over a long period of time, have the least amount of influence on a leader’s development, but when introduced at critical junctures in the development journey, can be amazingly powerful for broadening perspective, pro viding inspiration, and introducing new ideas. Often, aspiring leaders need input from senior leaders to identify appropriate learning activities to stimu late their development journey.

Aspiring leaders, when empowered, will be the most effective tool in ensuring transformative and sustained change. It is the influence of senior leaders, as well as role modelling, that serves as the catalyst to ensure aspiring lead ers use the knowledge, tools, and strategies to build and sustain a collaborative team

COVER STORY LEADERSHIP

10 EARCOS Triannual Journal

culture. Such cultural impacts go beyond the direct partici pants of mentoring and speak volumes to the broader work force.

Three Transformative Outcomes Achieved with Mentoring

Over the course of this school year, from August to June, I have been facilitating a Mentoring program that included five campuses from the Yew Chung Education Foundation (YCEF). This program is in its second year and has grown consider ably, taking into consideration all of the obstacles schools have faced with the pandemic. Claire Peet, YCEF’s Senior Manager L&PD and Quality Assurance, has been instrumental in work ing with me to develop and document the results of this pro gram. Originally, Claire was seeking to improve the number and type of candidates that were applying for leadership roles and various whole school projects. Most candidates had very little evidence leading any significant transformative changes within their team or beyond. Claire was concerned that if YCEF didn’t invest more time in developing promising aspir ing leaders, then those leaders would go elsewhere to seek development.

Since the program’s inception, what we are learning and achieving is far exceeding our original aspirations. In Febru ary 2022, at the midway point of the program, all participants completed a survey to share their experience in the program. These were the areas of the participant experience that the survey focused on and where we believe the transformation in both the leader’s and the school’s development is rooted:

• Leadership Development Projects: What were partici pants working on and how had it evolved over the course of the program? What was their relative level of confi dence to complete their project?

• Relationships: How has the program influenced their re lationship with each other and to the school?

• Retention: To what extent had the program influenced their desire to stay at their school and their belief that they could effect change in the organization?

Data collected for Leadership Development Projects indicat ed that a majority of projects had changed over the course of the school year, most of them only moderately, but 9 of 22 projects had changed significantly. On a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 indicating Not Confident and 4 indicating Very Confident, 5 of 22 mentees were not confident they would successfully complete their projects at the start of the year and no one was very confident they would successfully complete their projects. By February, everyone felt they would complete their projects, with 9 of 22 participants feeling very confident they would successfully complete their projects. There is an intrigu ing correlation between mentee confidence growth and pro

ject evolution. When exploring this with school principals in each of the 5 schools, they noted increased resilience as an unanticipated outcome from the program.

Data collected relating to Relationships was very positive. 14 of 18 mentors participating in this program indicated that this program positively influenced their relationship with aspiring senior leaders. Even more encouraging, considering the strain educational leaders experienced during the pandemic, was that there was a high level of trust between all mentoring pairs. 30 of 40 participants rated their relationships very trust ing, a 4 on a 1 to 4 scale, and 10 rated the relationships as a 3.

Lastly, regarding data collected for Retention, all participants indicated that this program had positively influenced their per ception of being able to effect change in YCEF. On a 1-4 scale, 22 of 40 participants selected 3 and 9 participants selected 4. More promising was that on a 1-4 scale indicating how likely participants would stay at their school as a result of this pro gram, 32 (both aspiring leaders and senior leaders) indicated that the program had a positive influence on their decision to stay at their school with 9 participants selecting 4, indicating it had a significant influence. This was further verified by partici pating school principals, one of whom noted that all mentees and mentors involved in this year’s programme had commit ted to remaining in the organisation for next academic year, despite the challenging circumstances in Shanghai.

If you would like to learn more about this mentoring pro gram and how your school can implement one, please email Michael Iannini and Claire Peet or visit this link, where Mi chael Iannini outlines the program in more detail, which also includes a downloadable PDF.

Claire Peet is an experienced Senior Leader, Coach and Learn ing Professional. In her current role she supports colleagues with their growth and development, as well as oversees pro jects that promote consistency in pedagogical standards, cur riculum and, most importantly, YCEF’s mission, principles and practices.

About the Author

Michael Iannini, founder and Managing Partner of PD Academ ia, is recognized by the Council of International Schools as an expert in Governance, Strategic Planning, Human Resource Management and Leadership Development. He is also author of Hidden in Plain Sight: Realizing the Full Potential of Middle Leaders. He can be contacted at michael@pdacademia.com

Fall 2022 Issue 11

STORYTELLING & DEEP LEARNING

How Stories Can Be Used in Any Discipline

By LeeAnne Lavender Storytelling & Service Learning Coach & Facilitator

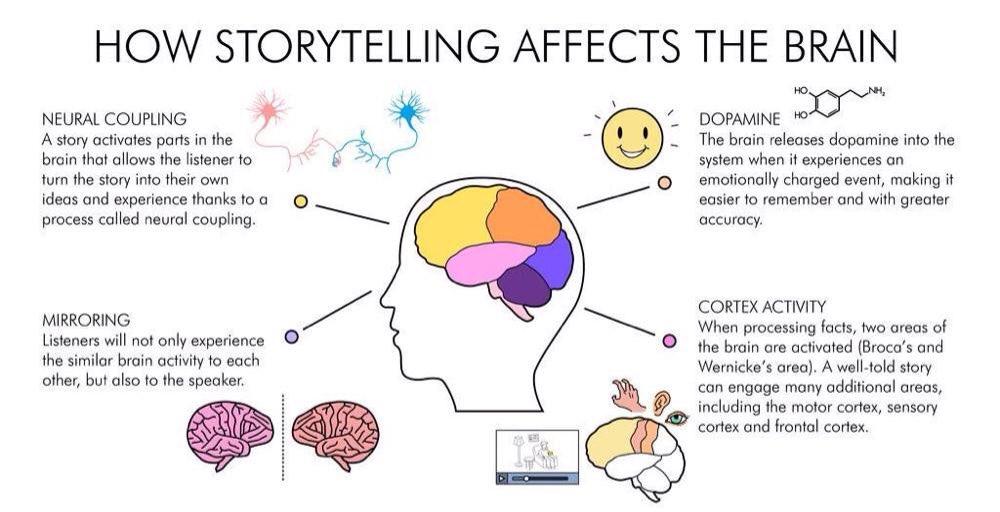

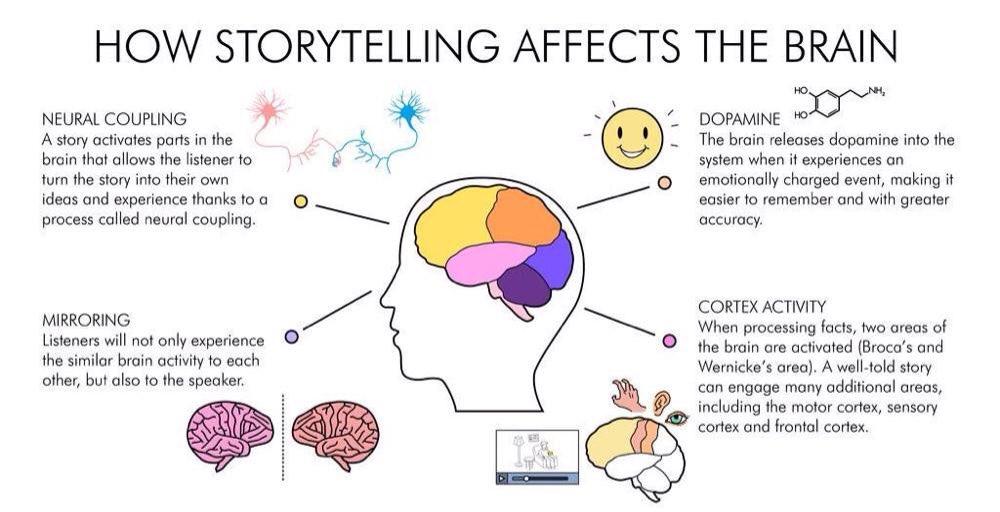

Did you know that storytelling affects the brain in the ways depicted in the image above? Isn’t that amazing? There are nu merous articles you can read online that explain the ways our brains respond to stories, including the article that served as the source of this image. It’s fascinating reading, and I’ve included some links at the end of this article.

Maybe you are a math teacher and you’re not sure how stories relate to your curriculum. Or you’re an IB teacher trying to fit all of your content into a busy school calendar. Where, you ask, would you find the time to tell stories? And how would that lead to deeper learning for your students?

The brain science around storytelling suggests that if we want students to really learn what we’re teaching (in any content area), stories are a key strategy for evoking engagement, em bedding information into our memories and creating compas sion and trust in our classroom. This isn’t an add-on but an essential way we can reframe our curriculum so it is meaningful and purposeful for our students.

What could this look like?

A group of educators from the Educators Consortium for Ser vice Learning (ECSL) recently engaged in a workshop where storytelling was used as a way to connect and reflect on key experiences from teaching during Covid. The primary tool for the workshop was a simple plot mountain (the five main com

12 EARCOS Triannual Journal

ponents of a story’s plot are exposition, rising action, climax, falling action and resolution).

Educators mapped their experiences from the past year us ing the plot mountain and then shared their stories in groups of four in breakout rooms. When they returned to the main Zoom discussion room, many similarities were noted amongst the shared stories. Most educators had experienced upheaval as a result of Covid-19 and experienced climax moments where their jobs changed significantly. Many learned they had strength to persist and keep going in the face of numerous obstacles. In sharing these stories, the teachers connected and felt a shared sense of catharsis and belonging.

Were our brains producing dopamine, cortisol and oxytocin? Absolutely. And this created an impactful experience that al lowed us to feel supported and heard, one that we will re member for a long time.

In your math, history or art classroom, you could use this sim ple plot mountain exercise to help students reflect at the end of a unit, or to review existing knowledge before launching into a new lesson. Your students could create a plot mountain that captures the story of an electron or a significant moment in history.

This is one simple way of incorporating stories into your curriculum in any subject area. You could also take curricular content and transform it into narrative. Are there historical figures in your subject area that relate to what students are learning? Tell those stories, have students watch videos about those people, or maybe even have students create digital sto ries in response to what they’re learning.

Stories will help your students learn and remember. Stories will help your students understand the world in ways that are more rich and purposeful. Stories will open up intercultural understanding and empathy.

Below are links to some excellent sites that provide additional resources for storytelling in your classroom. I hope they are helpful, and I hope you’ll experiment with telling and creating some stories in your classroom.

Storytelling Links for Further Exploration:

1. How Stories Connect and Persuade Us (NPR Article)

2. Storytelling as a Teaching Strategy (TeachHub Article)

3. Twelve Ways to Integrate Storytelling in the Classroom (Vis ta Higher Learning Article)

4. Storytelling Games for Elementary Classrooms (YouTube Video)

About the Author

LeeAnne Lavender is a Storytelling & Service Learning Coach & Facilitator. She can be contacted at leeanne@leeannelavender.com

Infographic highlighting the efectiveness of using ‘Whiteboard Animation‘ for storytelling @atayingaliveuk - www.staingaliveuk.com

Fall 2022 Issue 13

#NotSemantics

By Suhana Singh Madia, 11th Grade Singapore American School

Throughout middle school at Singapore American School (SAS) I had looked forward to becoming a highschooler, finally wearing the “cool” hoodie and accessing High School cafeteria. Yet calling myself a “Freshman” seemed like referring to some one else. To check if I was being unnecessarily sensitive, I asked my twin brother how he would like to be called a “Freshwom an”? His reaction – laughter fol lowed by a look of disgust. I also spoke to many girls in my grade. Some had not even noticed the term and while it made many others uncomfortable, they did not want to raise a concern. It was clear that a change was required. Equally clear was the fact if a change was to be made, I would have to be the one to voice it. I decided to bolster my conviction and belief with research.

Gender equality and women empowerment was prominently brought into focus when it was included amongst the 17 sustainable develop ment goals (SDGs) in 2015 (UN, 2015). Though efforts on gender equality have been made at national, regional and global fronts even prior to announcement of the SDGs, progress has been uneven. Measured on a scale of 0 to 1, where 1 denotes complete parity be tween men and women, gender parity was assessed at 0.68 by the World Economic Forum’s Gender Equality Report (WEF, 2021). This represents just a 3.6% improvement since 2006 and on the current trajectory, gender parity is not expected to be achieved for another 135years! A study of gendered languages (i.e. language which identi fies objects as masculine or feminine or sometimes neuter) spoken by 38% of the world population identified its association with low female labour force participation rates and regressive gender norms (World Bank Group, 2018). United Nations too has highlighted the role of lan guage in shaping societal attitudes and use of gender-inclusive language to promote gender equality (UN Women, 2017). I also came across increasing adoption of gender-inclusive guidelines (European Parliament, 2018) and precedents of prestigious institutions such as Cornell, Yale, Columbia and Dartmouth, which had replaced the term “Freshman” with gender-neutral alternatives.

Armed with the research and precedents, I approached the SAS School Leadership to replace the term “Freshman” with a gender-neutral alter native. The School Leadership kindly agreed and I am forever grateful to our High School Principal, Ms Nicole Veltze, Counselor, Ms Tina Forbush and High School Dean of Student Life, Ms Renee Green and for their encouragement and support.

During this process, I realized that the issue is far broader as American schools around the world continue to use this term. I therefore decided

to expand the initiative. I first contacted all international schools around the world assisted by the United States Department of State (more than 200 schools). On the advice of Dr Darrell Fine, Chair of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) at SAS, I have also started reaching out to around 1,000 independent schools in the US. Request is for these schools to consider the SAS example and replace the term “Freshman” with a gender-neutral alternative.

Response so far has been truly gratifying. Three schools, one in Africa and two in the US, which use the term have already agreed to replace it while five others are actively reviewing its continued use as a result of the outreach. Some are pushing the initiative forward and many are reviewing their broader DEI practices.

While I had not expected it, this journey has been fulfilling in completely unexpected ways. Students from schools as far apart as Ivory Coast and Bangladesh have reached out for guidance on their DEI initiatives. The initiative also brought me in contact with two amazing mentors, Ms Laura Light, Executive Director at The Association for the Advancement of International Education(AAIE) and Dr. Emily Meadows, LGBTQ+ Consultant for International Schools, whose guidance and encourage ment has further fueled my passion for the cause.

The experience has also enriched me with lessons I will forever cher ish. I have realized that standing for a cause is not about oneself but the impact it can have on others. If I believe in something, I will need to take the initiative instead of looking to others to take the responsibility. Being comfortable with putting myself out there, I know there may be resistance or even rejection, but I have to persevere.

Changing the term “Freshman” was never a battle of semantics or just changing one word. It was one of changing mindsets. The advocacy journey has made me alive to subtle biases which seem hidden in plain sight. Designating business leaders as “ChairMAN”, giving out “Business MAN” of the year awards when participants could be from any gender and using the term “KING size” to refer to something bigger, are just a few of the many examples out there.

While I have made a start with “Freshman”, it is clearly just a step in a long journey. Much more remains to be done but I draw inspiration from the famous proverb that “a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step”.

References European Parliament. (2018). Gender neutral language in the Euro pean Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/151780/ GNL_Guidelines_EN.pdf

United Nations (UN). (2015, September). Summit Charts New Era of Sustainable Development. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ blog/2015/09

UN Women. Guidelines on gender-inclusive language. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attach ments/Sections/Library/Gender-inclusive%20language/Guidelines-ongender-inclusive-language-en.pdf

World Economic Forum (WEF). (2021, March, 30). Global Gender Gap Report 2021. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gendergap-report-2021/

14 EARCOS Triannual Journal DEIJ

How Does Your Community Define Student Success?

By Suzie Boss Author and Educational Consultant suzieboss@gmail.com

By Suzie Boss Author and Educational Consultant suzieboss@gmail.com

In schools around the globe, new visions are emerging of what stu dents should know and be able to do by the time they graduate. Of ten described as a portrait of a graduate (POG) or learner profile, these student-centered visions have the potential to be much more than attractive graphics or catchy taglines. When fully embraced across a school community, a POG can align your entire system with a shared North Star that can transform teaching and learning.

So far, only an estimated 10 percent of school systems in the United States and a smattering of international schools have started on this journey. But momentum is growing, fueled by pressures to prepare stu dents for the challenges and opportunities ahead.

To better understand this nascent movement, co-author Ken Kay and I interviewed more than 200 school leaders, teachers, students, parents, and community partners who have engaged in visioning work. Their insights help to explain why today’s POG is different from vision state ments of the past. In Redefining Student Success: Building a New Vision to Transform Leading, Teaching, and Learning, we describe how this 21st century visioning process is reshaping everything from instruction and assessment to hiring and professional development.

This movement comes at a critical time, as schools around the world continue to wrestle with the challenges caused by the pandemic—from overcoming learning losses to addressing students’ social and emotional needs. At the same time, global comparisons show a continuing short age of pedagogies to develop and assess students’ abilities to be effec tive collaborators, communicators, critical thinkers, and creative prob lem solvers (Taylor, Fadel, Kim, & Care, 2020).The pandemic has likely set us further behind when it comes to transforming teaching and learning to meet these 21st century goals.

Where Bold Visions Can Lead

Despite the challenges of the moment, there is cause for optimism. In schools that have embraced a bold vision, students are learning deeply

by tackling real-world challenges in contexts ranging from sustainability to invention to global citizenship.

Elementary students in a community that values problem solving, for ex ample, created video tutorials during the early days of the pandemic to help their parents support them with online learning. In a school with a focus on global citizenship, students have created tiny lending libraries in neighborhoods they identified as “book deserts.” High school students concerned about climate change are helping to develop new curriculum focused on environmental justice—a goal that aligns with their school system’s POG. Their peers in a school where creativity is a learner goal have invented a breathalyzer bracelet to prevent drunk driving. Middle schoolers in a school that values critical thinking have partnered with scientists to identify the causes of pollution in a local lake and advocated for policymakers to invest in remediation efforts. These diverse examples are a reminder that well-defined visions do not shoehorn students into conformity. As Jennifer Klein and Kapono Ciotti explain in The Landscape Model of Learning, “The power and potential of using tools like the portrait of a graduate is to inspire students to deter mine their own definition of the horizon” (Klein & Ciotti, 2022, p. 109).

How to Get Started

The POG process typically starts with engagement of diverse stake holders in the broader school community. Together, they define the es sential competencies that students need to thrive in college, careers, and as engaged global citizens. Everyone in the community—teachers, students, parents, community partners, board members—needs to have a voice in these discussions so that everyone has ownership of the result. To encourage equity, school leaders may need to reach out to community members—including students—whose voices have not been heard from in the past.

The visions that emerge from these conversations tend to reflect wellestablished goals for 21st century leaning, yet are unique to each com munity. For example, at Mid-Pacific Institute in Honolulu, Hawaii, the

PORTRAIT OF A GRADUATE

16 EARCOS Triannual Journal

goal is for students to become innovators, artists, and individuals. In ternational School Dongguan in China has adopted goals for students to communicate effectively, demonstrate personal management, work collaboratively, become complex thinkers, and demonstrate global citi zenship. The vision at American International School of Johannesburg in South Africa is for students to be resilient, mindful, curious, globally connected thinkers and contributors.

To communicate their shared vision, school systems typically develop a graphic that conveys learner goals in a memorable way. In Armenia, where Teach for Armenia has led a visioning process to transform edu cation, a folk dance known as the kochari—performed by dancers who link hands—has provided a culturally relevant way to design a unified vision of student success. (To see examples of POGs from diverse con texts, visit the gallery at portraitofagraduate.org).

Bringing Your Vision to Life

Once a school community has adopted a POG, it’s time to begin the backward design process that will bring the vision to life. There’s no one path or timeline that will work in every context, but a few strategies are helpful to keep in mind.

Attend to culture: In our interviews with schools on the leading edge of transformation, we heard again and again about the importance of fostering the right culture to encourage innovation. In systems that have what we call a “green light culture,” strategies that have potential to transform teaching and learning are valued and encouraged. Barriers to collaboration are removed. Good ideas are shared, and “failures” are reframed as opportunities to learn. The green light reaches everyone in the system—from the head of school and division leaders to teachers, students, families, and extended community members.

A word of caution: Cultivating this culture doesn’t mean giving the green light to every wild idea that comes along. That can lead to distraction or initiative overload. The challenge is to encourage innovation that has the potential to advance your shared vision.

Empower teachers: Teachers are on the frontlines when it comes to bringing a new vision of student success to life. They need time and space to collaborate on problems of practice, along with professional learning to help them adopt new strategies. If the goal is for students to engage in real-world problem solving, for example, teachers need time to plan projects across content areas and, perhaps, with participation of community partners. If the student goal is self-management, teachers need to consider what that means at different developmental stages. In some cases, teachers have identified grade-level “look-fors” to help make POG goals more concrete.

Existing structures—such as professional learning communities (PLCs), learning walks, and peer-led professional development—can be refo cused on POG goals. To pursue a shared goal of deeper learning, one school leader recognized a need to replace traditional assessments that focused only on recall of required content. To rethink assessment, teach ers leveraged the existing structure of PLCs. Already comfortable us ing protocols and norms for collaborative inquiry, they used PLC time to critically examine assessments. That was a first step toward creating performance assessments that gave students more flexibility to demon strate their mastery of deeper learning goals.

Keep students at the center: By definition, the portrait of a graduate is a student-centered vision. Schools that are part of this movement are adopting more personalized learning strategies to keep students at the center. That includes giving students more choice over when and how

they learn, along with more voice in assessment. Project-based learning, student-led conferences, portfolios of student work, capstone projects, and mastery transcripts are among the practices on the rise in schools that are serious about redefining student success.

Keep your community engaged: Stakeholder engagement doesn’t stop when the POG is created. Especially in international schools, where staff and student turnover is anticipated, it’s important to revisit the vision regularly. Introduce parents who are new to the school community to the POG. Invite them to connect this vision with their hopes and dreams for their children. Share the POG with potential community allies. Invite them to partner with your students to solve authentic problems. Many schools also use their POG during the hiring process, asking applicants how they might support students in developing key competencies. Simi larly, the POG can inform professional learning. Schools that emphasize a growth mindset for students also encourage educators to set their own learning goals.

Embracing a bold vision for your school community takes courage and commitment. When you see students discovering their passions and honing new competencies that will prepare them for the future, take time to celebrate their successes. Document and share their compelling stories to breathe life and hope into your portrait of a graduate.

*

To encourage community conversations about Redefining Student Suc cess, download our free discussion guides for students and parents, avail able in both English and Spanish

References

Kay, K., & Boss, S. (2021). Redefining student success: Building a new vision to transform leading, teaching and learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Klein, J., & Ciotti, K., (2022). The landscape model of learning: Designing student-centered learning experiences for cognitive and cultural inclusion Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Taylor, R., Fadel, C., Kim, H., & Care, E. (2020, Oct.). Competencies for the 21s century: Jurisdictional progress. Center for Curriculum Redesign and Brookings Institution. Downloaded from https://www.brookings.edu/re search/competencies-for-the-21st-century-jurisdictional-progress

About the Author

Suzie Boss is an author and educational consultant from the United States who has worked with educators around the globe who are shift ing from traditional instruction to real-world project-based learning. She is the author of 10+ books, longtime contributor to Edutopia, frequent conference presenter, and PBLWorks National Faculty emeritus. Her newest book, Redefining Student Success: Building a New Vision to Trans form Leading, Teaching, and Learning, co-authored by Ken Kay, focuses on how schools are designing learning experiences that build students’ readiness to tackle future challenges.

* *

Fall 2022 Issue 17

After attending eye opening sessions with Ms. Katie Novak on UDL, I felt enlightened. At first, I was a teacher unaware of many helpful learning tools, and I always thought I was doing the best possible to nurture my students. However, when I took the course, it upgraded me to a new level of assisting my students in becoming expert learners. The most valuable takeaway I had was when Ms. Katie said, “Not one size fits all.” It has made me realized that different teaching strategies are needed to suit the diverse learning styles of students. The Course brought my attention to the necessity of teaching learners, showing me that true teacher should consider UDL as Understand ing the Diversity of Learners and providing ways to assist them move to wards becoming expert learners.

Understanding the diverse needs of leaners

CURRICULUM

Implementing

UDL in Early Years: My UDL Journey

By Pooja Kakkar Early Years Educator Stamford American International School pooja.kakkar@sais.edu.sg

Providing them with varied options to Learn and communi cate their knowledge

Becoming expert learners

Understanding the diverse needs of learners and responding to it with range of tools and strategies: Living in an era of globalization, students in our class come from diverse cultural backgrounds and have diverse needs. I always believed that making healthy connections with students is a vital investment for understanding their needs. Students will learn only if they feel connected to their peers and teachers, and safe to voice their opinions. Giving listening ears to their situations, feelings, emotions and attending to the same builds up their social emotional learning and simultaneously gives a chance to teachers to understand their needs.

However, the barrier that I was facing initially was to connect with those who have EAL needs, and English is not their first language, and students who have special needs. To cater to such students, the UDL framework helped me discover different ways of communicating with them and building that vital secure relationship. In order to make them familiar about the classroom routines I made google slides which displayed the classroom routine visu ally as well as spoke it using an audio in their language. After going through the instruction verbally, I played the audio in different languages. This was exceptionally useful in making students feel respected and included in their classroom environment. As students in my class are too young to be able to determine their choice of learning, observing them over time and keeping notes on different learning styles that work best for them helps in embracing variability in the classroom.

Following UDL framework, I could respond to their diverse needs in an ap propriate way. The framework stresses the importance of nurturing a child’s executive function development. This in turn assists children in remembering and following multiple step instructions, and carrying out their routine con fidently. Executive function and self-regulation skills provide critical support for learning and development. I made an action plan for my learners that included establishing clear goals and displaying visual routines to support their independence.

This truly helped my students perform multiple step tasks without needing repeated instructions. Using the power of visualisation was a very effective technique which taught them problem solving skills and to become inde pendent in their early years. Visual support:

• Helps children understand where to find things and where they belong.

• Ensures that directions are provided both verbally and visually, a crucial aspect of UDL within an early childhood classroom.

18 EARCOS Triannual Journal

You must have heard of teachers using the rhyme “Criss cross apple sauce” during circle time. I was one of them. I had visuals with the rhyme on them, and I made sure students sat that way. It never oc curred to me that my ways could be wrong. However, I felt so guilty after getting to know about UDL framework. I learnt that there is no reason to use that rhyme if my students are on the carpet with me and attending the session well. If they are attentive and love to learn in their own ways, then why not? It doesn’t stop them from learning if their legs aren’t crossed.

the concept, they were simply not in the mood to demonstrate their knowledge. I removed such barriers with ‘Multiple Means of Action and Expression.’ Instead of having just one means for students to rep resent their knowledge, we provided students with different ways to display their knowledge. The students could now either point, name or engage themselves in their preferred activity to give their response. Stu dents who needed support to strengthen their skills and have better understanding of the concept were engaged in collaborative activity. This helped build confidence in them to participate without being the centre of attraction.

While reading is a skill we must learn, picture processing is an ability we’re all born with, and the language of pictures is universal.

Engaging the five senses of the pre-schoolers provided a unique way to represent the information. In my class, there were students who were auditory, some preferred learning by seeing and then there were oth ers who preferred to touch to learn the concept. To meet the diverse needs of the learners, I began to present the concepts being taught in different ways. For example, to teach them the basic concept of hard and soft, a cooking session was organised, technology was incorporated, and we also visited PE room to have a physical experience.

Providing children with varied options to learn and communicate their knowledge

UDL framework talks about three principles:

1. Multiple means of engagement

2. Multiple means of representation

3. Multiple means of action and expression

These 3 principle are the guidelines of the UDL framework.

As pre-schoolers require lots of encouragement to interact with peers, they are taught through role modelling and different collaborative activi ties that assist them in befriending other classmates. Once I realized this was the educational need of each learner in my class, I made it my goal to meet this need, and began to engage them in collaborative work and games. These were helpful but not for those who required extra assis tance in using words to communicate their needs. Those students were left behind in my efforts. There were also those who were not confi dent yet to participate and tried to avoid taking the spotlight. I Recog nised these barriers, and to overcome them, the UDL principle ‘Multiple means of engagement’ guided me. I began searching for engagements of different difficulty levels to help my student with their social-emotional skills and encourage them to actively participate in activities. I initiated activities ranging from sensory to art to free exploration. I also began to use the voting system in my class so children could vote their favour ite learning centre and give feedback on what exploration they like to continue or try. Multiple engagements also helped my EAL students engage and attend for longer time periods. After employing this tech nique, I saw that all of my learners were engaged in what they are doing, and the activities they were participating in were suited to them and were at the right level for them. To ensure that activities are personally meaningful we can, for example, connect them with students’ previous knowledge and experiences, highlighting the value of an assigned activity in personally relevant ways. Also, adult or expert modelling can help demonstrate why an individual activity is worth pursuing, and when and how it is used in real life.

Assessment has always been a part of every curriculum. We observe children on regular basis and discuss as a team what best can be done for them. However when it came to the point where pre-schoolers occasionally had to demonstrate their knowledge, it became a tricky situation. This was because even when they knew everything about

UDL coursework ultimately guided me in the direction of empower ing my students to become Expert Learners. It facilitated creating a safe environment where students feel a strong sense of belonging in the classroom, a setting where they feel safe and confident enough to express their ideas and explore. It assisted in creating a sense that it is alright to fail or make mistakes amongst the students. It helped them take ownership of their work and ask relevant questions to build their knowledge. All students will become expert learners if barriers are re moved When we …

- give our students choices, - help them reflect on the effectiveness of those choices to better un derstand themselves as learners, - support them in applying what they learned about themselves to new situations

- build their ability to do these independently over time … … then they are able and willing to take ownership of their own learn ing for their lifetime and become EXPERT LEARNERS.

About the Author

Pooja Kakkar is a passionate Early Childhood Professional with Masters in Early Childhood Education and a Diploma in Montessori Education and extensive International School experience across different func tions. Over the course of her career, she have developed exposure in international settings having lived in the United States, Singapore and India.

Fall 2022 Issue 19

CURRICULUM

A Plea for Paideia in International Education

By Jared Rock HS Communications and English Teacher Seoul International School

Introduction

The major guideposts of current educational practice come in lists of skills and standards, under the umbrella of some curriculum or program, whether it be IB, College Board AP, Common Core, or any variety of others. When talking to teachers, administrators, students, or parents it is common to hear pronouncements like “we’re an IB school” or “this is an AP school,” so that the branding of a school through its (often purchased) package of skills and standards appears readily accepted as some sort of definitional description of the institution itself. A moment’s reflection reveals that such definitions are more deflection than clearly pointing to who and what we are. The ability to overlook such lapses is, I believe, symptomatic of (as a convenient shortcut for) a pervasive distraction we currently face.

I will start by asserting what I think will strike most readers as an un controversial claim: neither skills nor standards, on their own or under a program of any kind, are sufficient to good education. The reason for this insufficiency is that good education is always holistic, and the lists by which we make curricula are necessarily atomistic. Atomizing learning into its building blocks has practical benefits, but it would be foolish to pat ourselves on the back for a job well-done having guided our stu dents through these steps merely. Good education is both infinite and unfinishable, its outcomes always more than the sum of its parts.

The question of finding the real value of education against the program matic roadmaps of skills and standards must come back to each indi vidual school itself, to the living, interacting community that constitutes it. Here, at our institutional homes, we know its value through our daily work, one that comes in the growth of each person as a person. Paideia is the beating heart of good education, its prizes are inner growth, good character, and wisdom.

Is there a problem?

The relationship between paideia and the curriculum of standards and skills is not one fraught with antagonism by default, but I will propose to readers that a current dilemma does present itself in a classic “wood for the trees” problem of focus. The amount of time we are apt to spend discussing skills and standards for their own sakes threatens to over shadow our larger goals and color our daily actions as educators, per haps imparting upon pupils and parents the wrong lessons about what education is and should be. When a class becomes a set of standards to complete and skills to master, with an end-goal of preparing students to enter another such class and repeat the process, when school’s purpose

is to equip students with a skillset so that they can be successful in col lege and the workplace, then it is easy to drift into treating skills and standards themselves as the primary value in education.

The classic conceptualizations of techné and paedia as two currents in the river of education, the former concerned with scientia and the latter with sapientia, can be of some use in recognizing a problem of focus and balance, if one exists. A skills focus is the realm of techné, and derives its value and justification by its utilitarian telos. Of course, this contributes invaluable benefit to a healthy society, and it is institutionalized as the highest priority of our universities’ professional schools, our vocational schools, and our job training programs.

We should, however, ask ourselves the extent to which our schools un derstand and communicate their purposes and values through college acceptances, workforce preparation, appeals to nurturing critical think ing, and the like. If this is the main value we flag in our program then it is likely to become the magnetic north we set to the life compasses that will guide alumni beyond our halls. Consider then the outcomes of such a view of life and of education: the picture becomes one of a highly learned and clever person who knows how to play the game and has a well-lit path for success in professional life, beyond which darkness lies, leaving a trail of fleeting accomplishments and the frustration of being so capable and intelligent yet so utterly lost in life. Of course, the outlook for real people is never so bleak because our human interac tions fill those gaps to some extent, but the exaggerated picture is the unalluring promise techné alone, and should give us pause to consider the extent to which it drives our decisions. If our students are seen as some product to be filled with skills and critical thinking capabilities, we risk viewing such “filling up” as good education. The really pernicious thing about this oversight is not to be found in any malicious intent or negligence, but how constant distraction blows us so gently off-course to eventual dehumanization without us ever realizing it.

The telos of our schools’ education should be helping our members live a good and fulfilling life, a purpose and value far beyond just the profes sional utility of schooling. The tradition of paideia comes in here, going to the very core of active interrogation, reflection, and formation of the self. Paideia rests upon knowledge and skills; it is informed by scientia and exists comfortably alongside techné, but its path extends to sapientia. The problem is not one of mutual incompatibility, but how we act out and understand our purpose.

To consider whether or not a problem exists, each school must examine itself to see what it talks about as the source and value of education, and what it shows as its purpose through daily work in classrooms, depart ments, and faculty meetings. While paideia is probably what most of us claim to be education’s ultimate value, it may be that it gets scant atten tion in many of our schools. My plea here is that if we find our practices misaligned with our higher goals that we use the language of paedia to adjust the attention of our meetings, classes, and other interactions. The purposeful use of language to drive educational practice and priorities and communicate common understandings and goals is a known tech nique. Consider some of the previous and current jargon that saturate our profession, such as SMART goals, learning styles, formative and sum mative, transfer skills, transversal skills, scaffolding, thinking routines, and so on and so on. My proposal is to use the same technique to discuss more durable, perennial issues of education as we carry out its work in this globalized century and in our varied contexts.

Paideia in our schools

Paideia will look different in every school, especially as each international school will use its own unique meeting of cultures and perspectives to

20 EARCOS Triannual Journal

In the abstract, Emily Dickinson’s “Evenings of the Brain” (Dickinson, line 10 in F4281 ) provides a rich conceit for a universal conception of paid eia. It is in this unsettling internal darkness that “the Bravest” will “grope a little” (Dickinson, line 13 in F428) and through that effort end up adjust ing their inner sights, expanding the known territory of one’s self. The rewards are perhaps best expressed in another of her poems, with the paradoxical discovery of “finite infinity” within each person (Dickinson line 8 in F16962 ), but to get there one must make a continual habit of this kind of self-probing, and teachers and peers are constant compan ions pushing one another to these points of growth. While there is no one correct path, all paideiaic practice emphasizes the importance of the examined life.

One thing that clearly distinguishes the paths of paideia and techné is that paideia is necessarily intense and uncomfortable, pushing us to know ourselves more intimately (in-line with that most famous of the Delphic maxims), which also means letting go of much we hold dear or find comfort in, continually questioning ourselves, and facing vulner ability along our outer limits by pushing ourselves and one another to aporia. We constantly ask what is right and wrong, how to live good lives, how to make good choices, and what it means to be human.

The process for the individual is much the same as the process for the school community as a whole. A school that commits itself to paideia should tend to the reflection and growth in all of its members and organization as a whole. This can give schools a firmer sense of mission and common purpose, and lead to better collaborative forging of vision, community, and good governance. The most influential modern con ceptualizations of paideia for today’s schools are probably those found in Dr. Mortimer J. Adler’s pedagogical theory, though the living voices of paideia’s central role in a good life and good society can be heard in our contemporary intellectual powerhouses like Dr. Cornel West and Dr. Roosevelt Montás. The one common necessary element is that our schools must be true learning communities with teachers whose mo tivation to teach rests on their desire to continue their own learning, and school practices that facilitate and require progress in the learning journeys of all its members.

1https://www.brinkerhoffpoetry.org/poems/we-grow-accustomed-tothe-dark

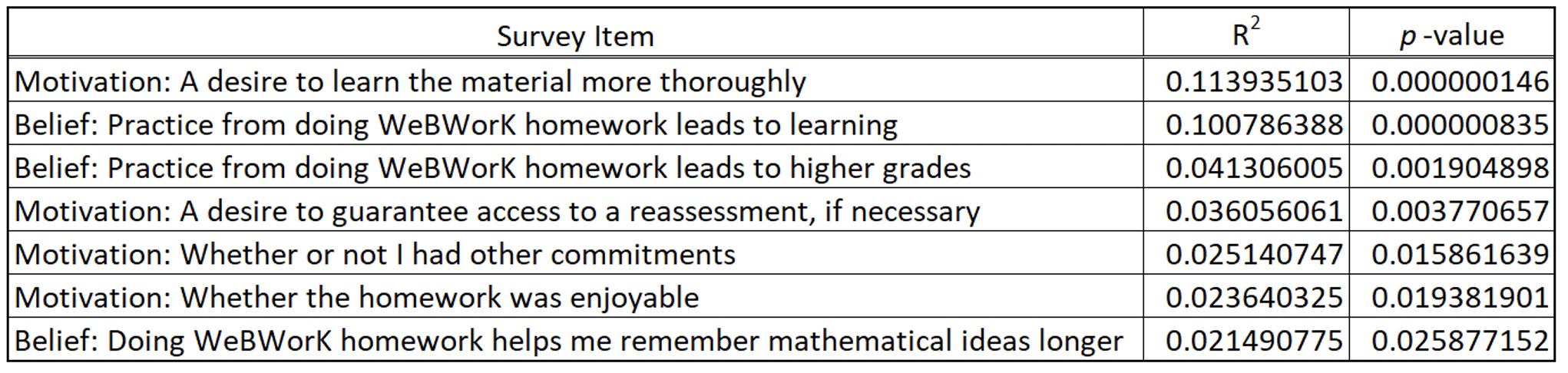

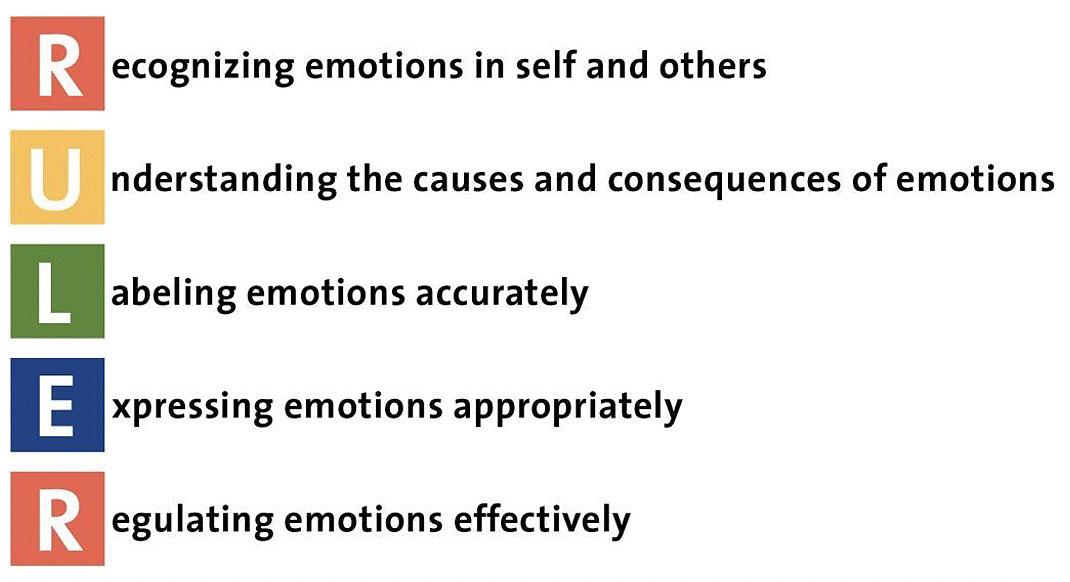

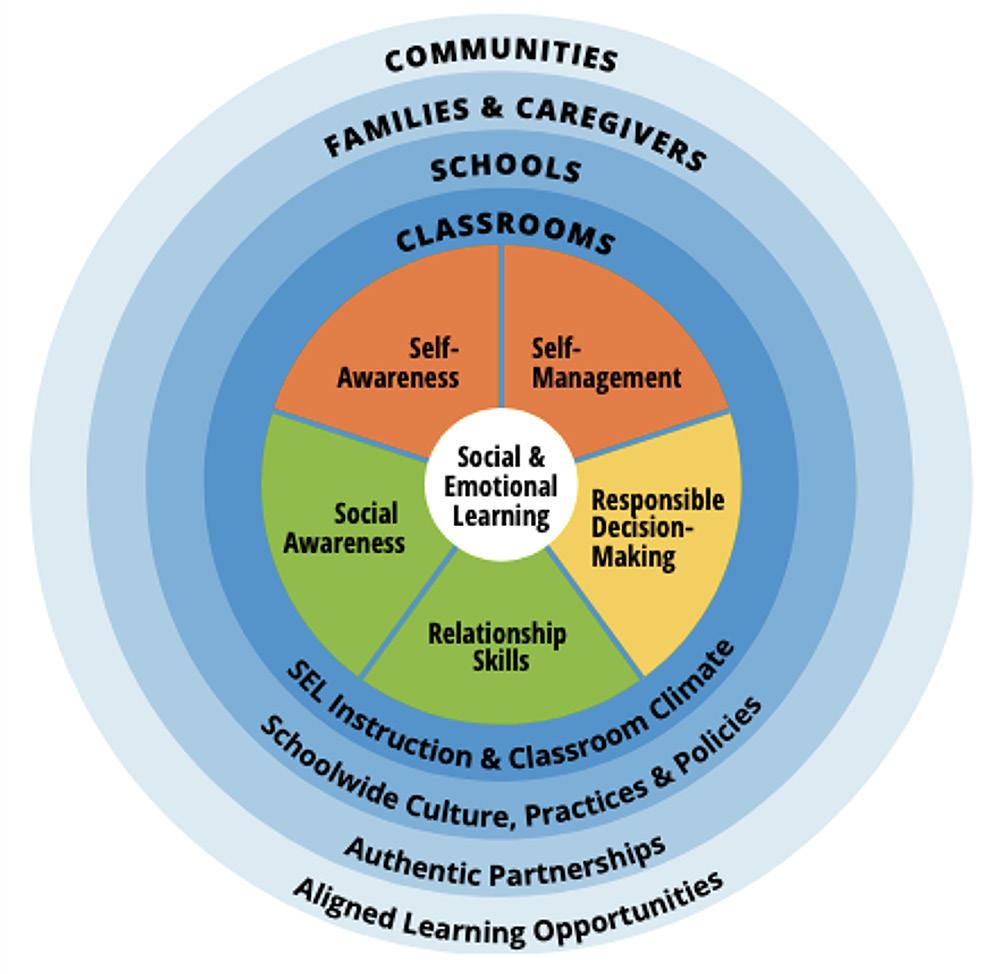

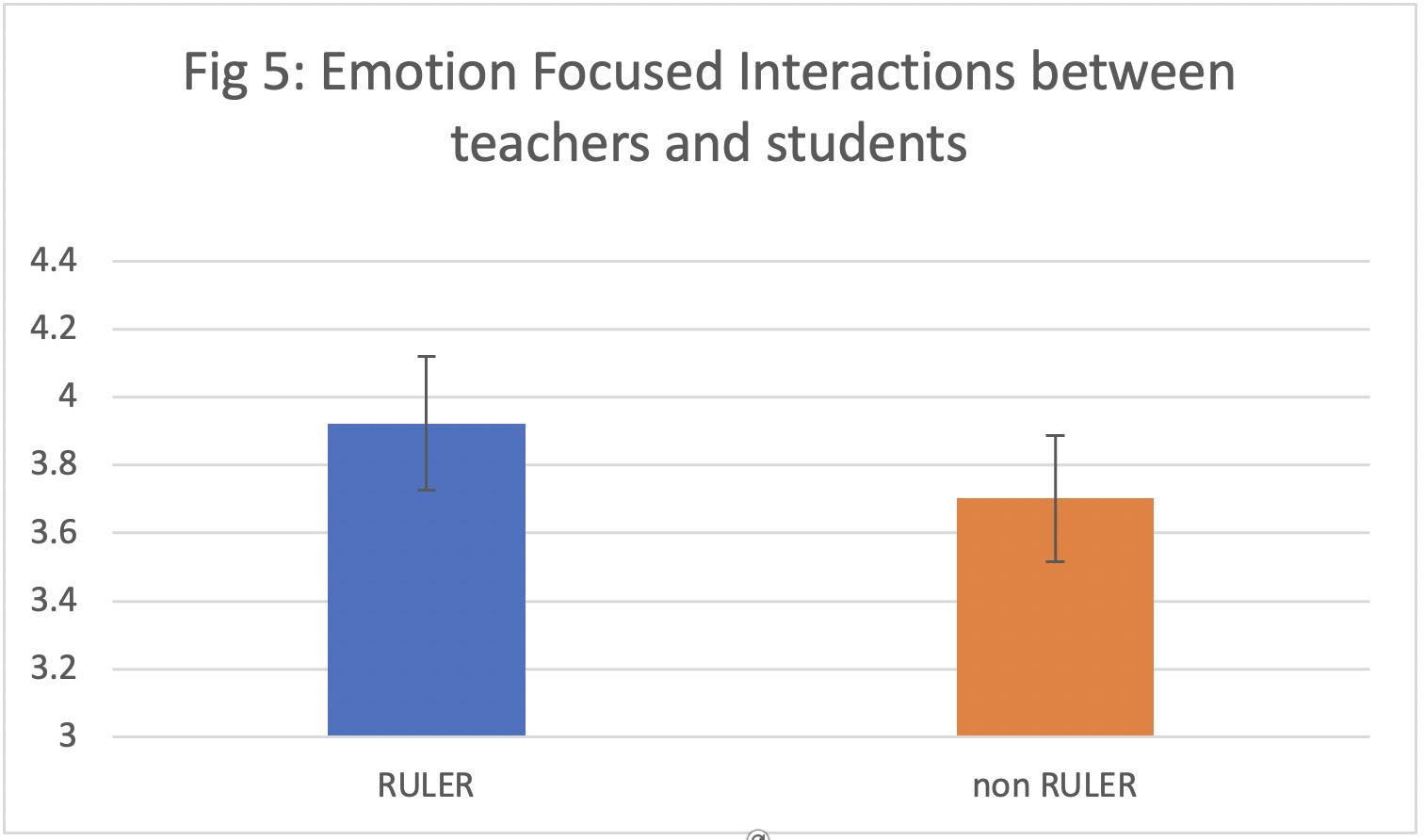

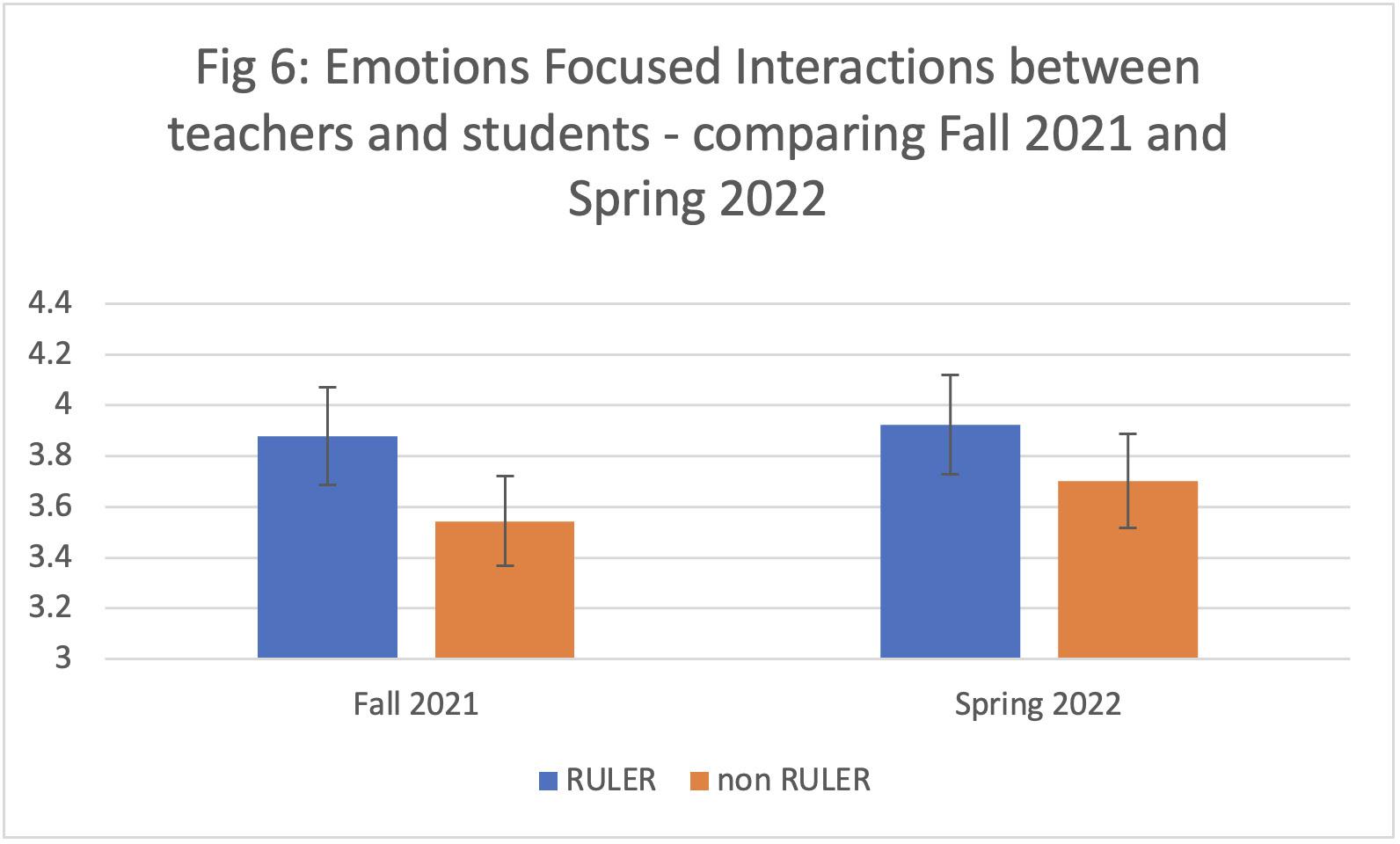

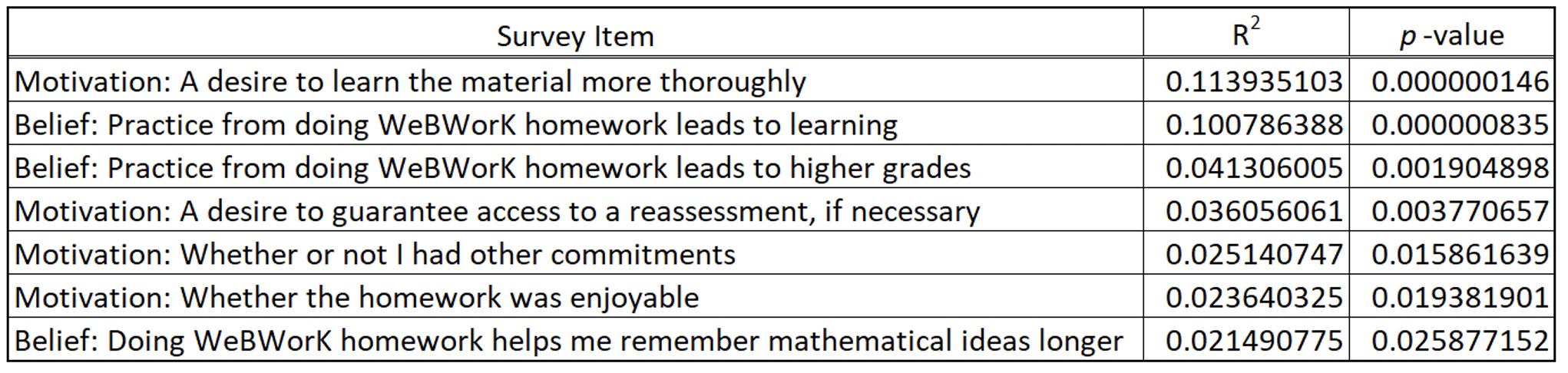

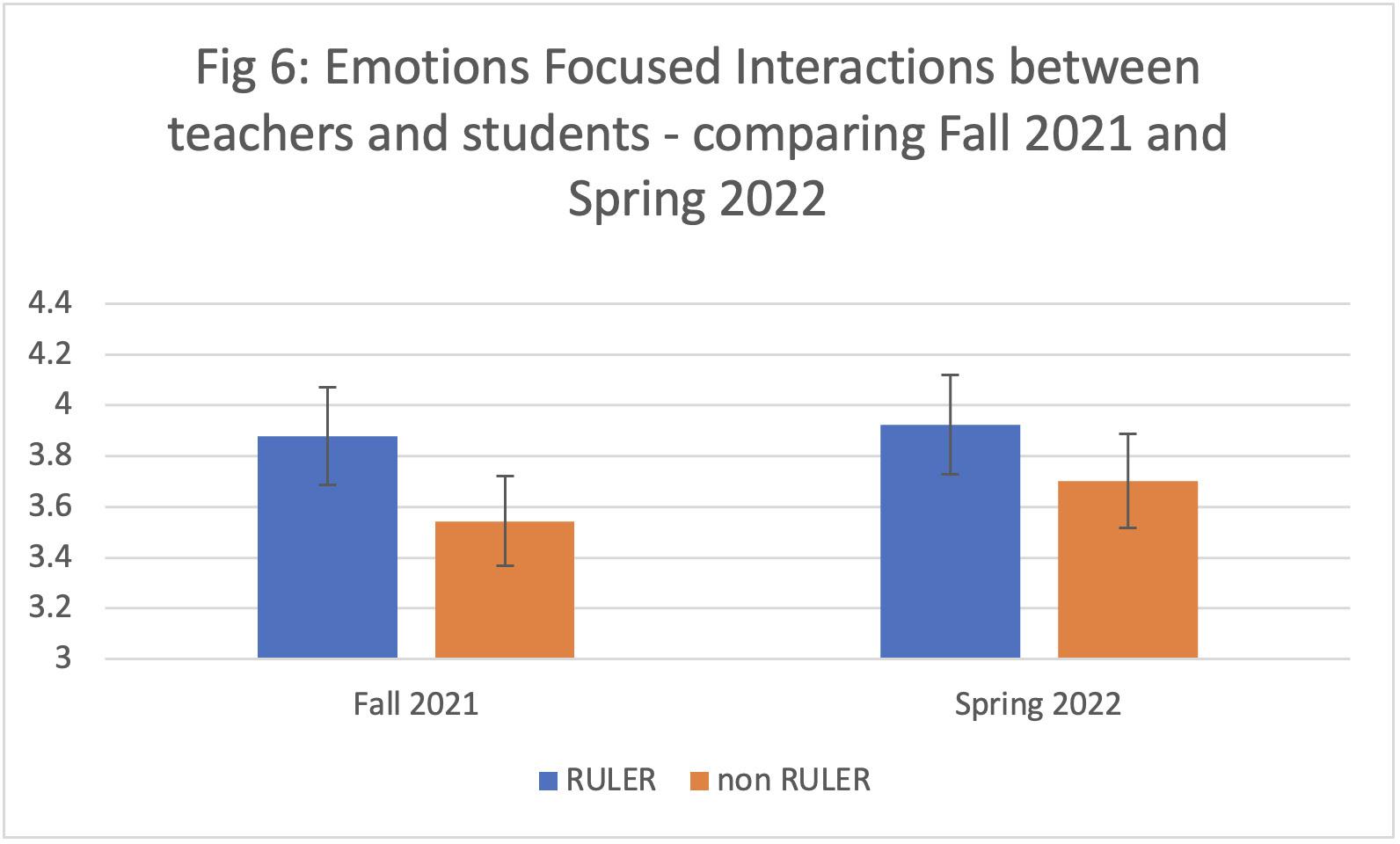

2 https://hellopoetry.com/poem/3700/there-is-a-solitude-of-space/