Colonel Josef Albert Meisinger was given the nickname the Butcher of Warsaw while Richard Sorge was once described as the greatest spy there ever was by Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond books. The two men’s lives entwined in Tokyo, when Meisinger arrived in Japan as head of Gestapo operations across Japan and China, in May 1941.

Sorge was a German national but had been born in Baku, Russia. His father was a German engineer, his mother was Russian. However most of his education took place in Berlin. While at school he volunteered to join the German army like many students seduced by a love for the Kaiser and the mother country. Early in 1915, he was wounded by shrapnel and invalided back to Berlin, where he finished high school and began university. Yet in 1916, he volunteered again, was sent this time to the Eastern Front and was wounded twice more. He recovered but thereafter walked with a limp.

He had come to Japan in 1933; over the intervening years he had become a well-established and respected journalist for several German newspapers. This was a cover. His principle activity was spying for the Russians, an activity he had undertaken since joining the Communist Party of Germany in 1919. From China he passed secrets from both the Japanese and the Germans and was now part of the Department Four of Red Army intelligence. Being German and wartime-decorated he found it easy to strike up friendships with the local German military seconded to advise Chiang Kai-shek. His Japanese secrets came from the relationship he had with the Japanese journalist and communist sympathiser, Hotsumi Ozaki.

He was then despatched to Japan in 1933; the burning question that the Red Army wanted answered was had the Japanese plans to invade and occupy the far eastern provinces of the Soviet Union?

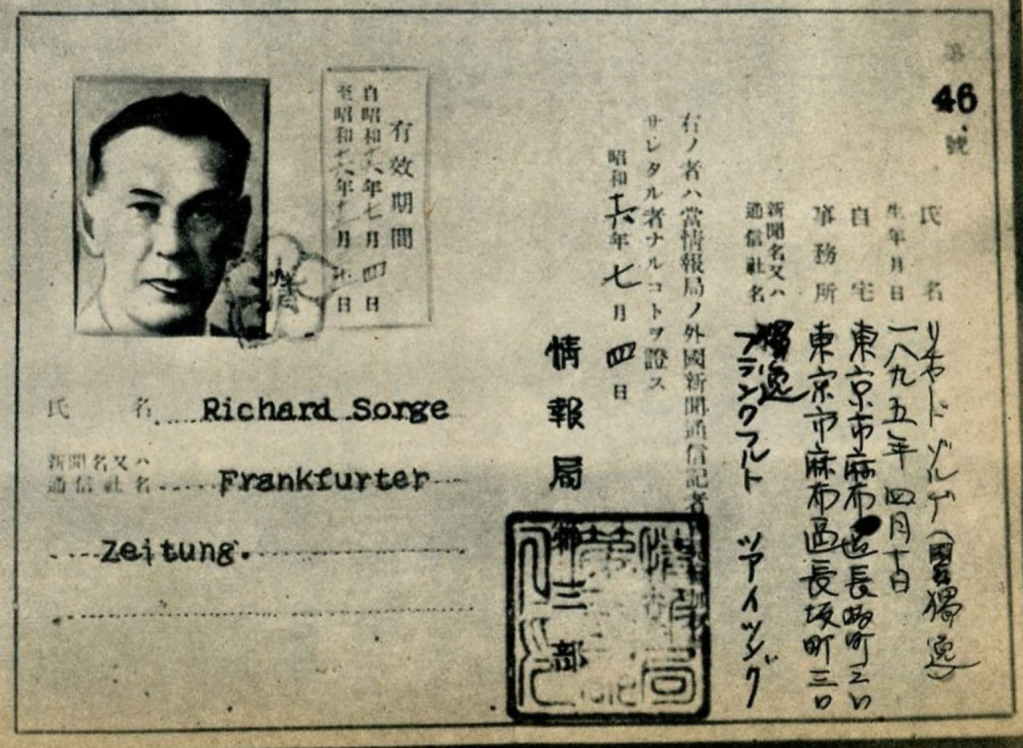

He became a member of the Nazi Party and eventually a reporter for Frankfurter Zeitung. On arrival he found a flat and a Japanese girl-friend, Hanako Miyake, a waitress working at the German restaurant Das Rheingold. Here he was able to cultivate contacts and ultimately his success in Japan was down to the network of contacts he nurtured which, by the time Meisinger arrived, included the German Ambassador Eugen Ott. Ozaki now back in Tokyo continued to supply Sorge with information from a Japanese perspective. This showed that the Japanese did not plan to strike north into Russian territory but south into the rest of Asia. But it was Ott who unwittingly would provide most.

The Ambassador had been completely fooled by Sorge. He gave him access to highly confidential files for example; Sorge was the author of several reports sent to Berlin under Ott’s signature; Sorge had an affair with Ott’s wife; Sorge too was responsible for editing Der Deutsche Dienst, a news bulletin for the Embassy staff and German community. Sorge was also a close friend of Kapt zS Litzmann, who was then the German Naval Attaché in Tokyo and who permitted Sorge to read the official naval war diary. Another prominent member of Sorge’s circle was Rudolph Weise, chief of DNB (the German press agency) in Tokyo, and Susi Knoller, the secretary to Werner Klingeberg who was helping to organise the planned Olympic Games in Tokyo.

There is some cloudiness as to whether Meisinger was aware of Sorge’s activities prior to his arrival. It would seem that at best, the German authorities in Berlin had recently started to suspect that Sorge might be a Soviet spy and so he was on a list of people who Meisinger should discreetly vet. The claim that Meisinger was sent to Japan purely to vet Sorge is sometimes made but is dubious.

A senior officer in the SS, Walter Schellenberg, wrote in his memoirs in 1948, that prior to Meisinger’s despatch to Tokyo, the Nazi’s had grown suspicious of Sorge because of his political past but also decided that they could profit from him with his ‘profound knowledge and that he should give the Germans intelligence material on the Soviet Union, China and Japan.’ Of course he was unaware that indeed Sorge was already doing this via Ott as a way of diverting suspicion. However the accuracy of the memoirs, written when Schellenberg was on trial, has been questioned. It is easy to see that he was both being wise after the event and trying to elevate his expertise and legacy. This is borne out by the later statements made by Ott and Meisinger,

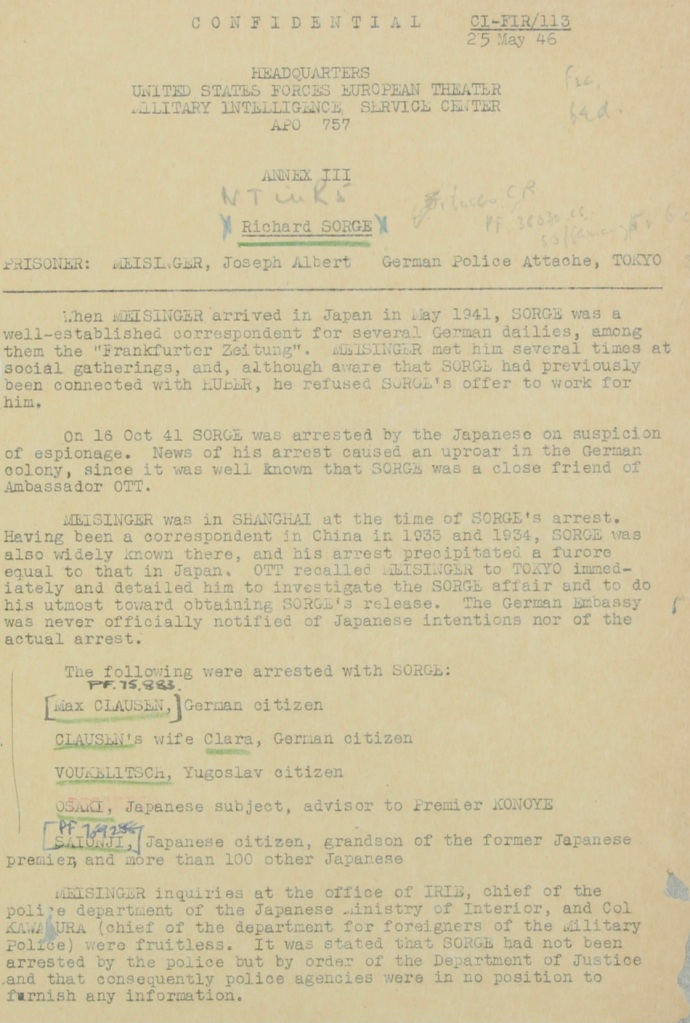

After Meisinger was arrested at the end of the War he said, under interrogation by the Allies, that he had only met Sorge several times at social gatherings, and although he knew that Sorge had worked for his predecessor and that he was a close friend of Ambassador Ott, he claimed he refused Sorge’s offer to continue in this role. As there was nothing to lose by confiding that he he was investigating Sorge this throws up more doubt about how much he knew before he came to Tokyo.

How close their relationship was might be open to question but it was more than casual. Even if Sorge was a known Soviet spy, Meisinger would also know that he would be a useful source of intelligence about nefarious activity within the German community. In the past, Sorge had also cultivated Ott’s trust by supplying him with intelligence about the Japanese, and it is likely that he provided similar information to Meisinger. Both men were also both susceptible to the allure of alcohol, playing poker, casual affairs, and both would mix in the same social circles in the same German bars and restaurants in Tokyo. There are reports that they were great drinking buddies. What is unknown is whether Sorge ever suspected that Meisinger might be investigating him. If he did he was able to string Meisinger along to the extent that Meisinger wrote reports that exonerated Sorge from any spying activities on behalf of the Russians.

Only six months after Meisinger’s arrival Sorge was arrested by the Japanese on suspicion of espionage – along with a number of others who were part of the inner spy ring including the Germans Max Christiansen-Clausen and his wife Clara (or Anna), a Yugoslavian by the name of Branko Voukelitsch, Osaki-san (who was noted as a brilliant advisor to the Prime Minister Konoye), and Prince Saionji; and also more than 100 other Japanese who might have collaborated in some way.

The Japanese had been suspicious of Sorge for a number of months even before the arrival of Meisinger, and had started to put together a list of people with whom he was known to associate with but they did not start arresting the key suspects until early October, 1941 with Sorge himself arrested on 19 October. (Though in the records there are several different dates.)

Meisinger claimed that Sorge’s arrest was a great shock to Ambassador Ott and to himself. (Which also throws into doubt that he was sent to Tokyo to vet Sorge.) Indeed he threatened to send any person who spread the rumour that Sorge was a spy to a concentration camp. It also seems to be the case that if Berlin and Meisinger had suspicions these had not been passed on to Ott for some inexplicable reason.

Initially he and Ott believed that the Japanese had committed another of their blunders for which they were legendary. Meisinger claimed that at the time of the arrest he was visiting Shanghai – where the news of Sorge’s arrest was equally shocking – but went back to Tokyo but when he tried to find out details of the arrests – from Irie-san (head of the Police division within the Ministry of the Interior) and Col Kawanura (head of the Military police dealing with foreigners) – he was rebuffed.

Ott apparently decided not to consult with Berlin but to try and engineer a release using his own contacts in Japan. He discovered that the Japanese were not blundering. Sorge was a spy and the Japanese were not going to release him. However when they arrested Sorge they did not know whether he was a Nazi spy; a double agent for both Germany and Russia, or whether he was just working for the Russians.

Ambassador Ott was at least able to visit Sorge in jail and asked him he could do anything but Sorge is said to have replied ‘There is nothing that can be done but I would like to thank you for everything. We shall not meet again.’

When Ott and Meisinger reported the arrest to Berlin they tried to minimise their relationship with Sorge, which would again throw up doubt about the Meisinger knowing about Sorge’s activities prior to his arrival. However an agent working for the Abwehr in China heard a different, albeit garbled story about Sorge and his closeness to the Embassy, and reported it to his bosses in Berlin. That was when Ott was sacked. However by some means or another Meisinger managed to save his skin. (It is thought that he likely blamed Ott, and also repeated his story that he only had a passing acquaintance with the spy.)

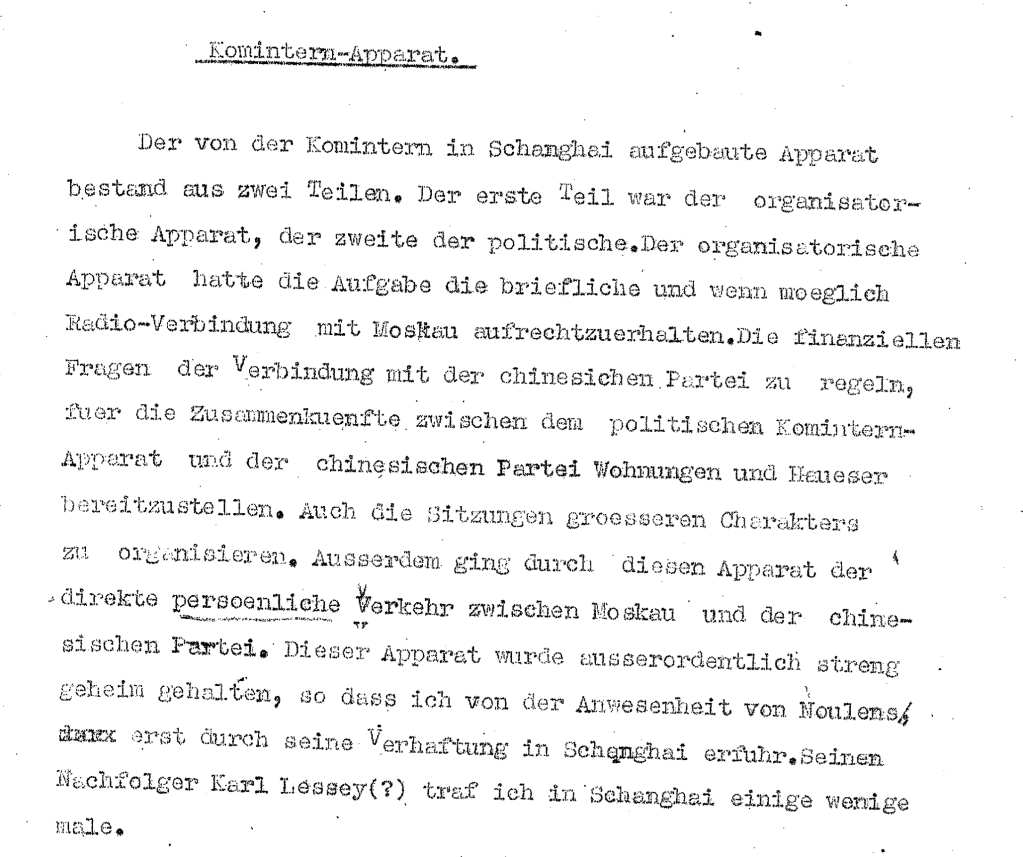

In December 1941 a document The Confessions of Sorge was received at the German Embassy. It was in two parts, the first covering Sorge’s activities from 1924 to 1929, and the second covering the period from 1929 to 1941.

In the first period, Sorge said he was active as an organiser and inspector for the Comintern in Scandinavia. His residence was Berlin and he was in direct contact with Moscow. On one of his frequent trips to the Russian capital he was ordered to work for the Red Army, and sent to Shanghai in 1933 as a correspondent for the Frankfurther Zeitung and then to Tokyo in 1934.

During the following years, Sorge succeeded in establishing a large network of informants; he collected military, political and economic information which was sent by radio to Moscow. It was the previously mentioned Max Christiansen-Clausen who operated the radio.

Meisinger told his interrogators that he had doubts about the veracity of the confession as it was not signed by Sorge and the only name it mentioned was Clausen.

This was untrue. While most of the confession was destroyed by the German Embassy and by fire caused by the Allied bombing of the capital a few pages were not destroyed and these were found by American forces and are now kept by the CIA. The pages are typed in German by Sorge and are extensive and detailed – albeit about his time in China. Possibly he was more circumspect when it came to his time in Japan but it is clear that this is Sorge speaking and typing. After all he did confess,

‘I reached the conclusion that Germany could make no further contribution to the world—in terms of ideas or otherwise—and that England and France were equally incapable of helping Germany or other nations. No fatuous declamations on spirituality of high ideals could shake this conviction of mine. Since that time I have never been able to tolerate protestations of idealism or high purpose by leaders of a nation at war, regardless of the people on be‐ half of whom they espouse them.’

It was only in April 1942 that information about Sorge was sent to Ott and Meisinger from Berlin. This outlined that Sorge had been born in 1895 in Tiflis, joined the KDP (German Communist Party) in 1919, and in the same year briefly became editor of the Communist daily Bergishe Arbeiterstimme. He was a frequent visitor to Moscow (as noted above) and appeared in several Russian almanacs under the alias R Sonter, a pseudonym he used as an author.

He had not been registered as living in Germany since 1929 and how he managed to obtain a valid German passport in 1933 was not known. Clearly this was information sent in an attempt to cover up how the Germans had in their innocence or incompetence aided Sorge. Meisinger turned this over to the Japanese so as to show good faith, and to prove that he was not in cahoots with Sorge. The Japanese remained unconvinced. After all they had Sorge’s confession and likely this gave them information that contradicted what the Germans claimed.

The Japanese also told him that Sorge had been in possession of several excellent letters of introduction from the German Ministry of Propaganda when he arrived in China in 1933, which he had used to form a network of influential friends. They said that the Sorge affair had caused a deep rift in German-Japanese relations which could only be healed if proof could be brought that Sorge was not a German but a Russian national. However Meisinger said he refused to do this unless the Japanese provided an official report of Sorge’s arrest. Of course he could not provide that proof and neither were the Japanese inclined to give the Germans anything but the most cursory of information; Meisinger said that relations did suffer visibly from the Sorge affair as anti-foreigner propaganda increased in intensity.

Both Ott and Meisinger made attempts to distance themselves from Sorge but largely due to a report that Meisinger had submitted to Berlin, Ott was summarily dismissed from the role of Ambassador in December 1942. He was told to return to Berlin but wisely decided to live in Peking. However the Japanese authorities were convinced that Ott had no inkling of Sorge’s Russian links, and also thought that if he had returned to Berlin he would have been killed.

However, the Japanese too were highly embarrassed that Sorge had been able to penetrate the highest levels of government. Although stories were released to the press in May 1942 they downplayed the significance of Sorge and trivialised the impact that he had. The ministry ordered newspapers not to run the story at the top of their front pages, not to use a headline larger than four-column length, and not to use pictures. Like Ott and Meisinger, they wanted to evade responsibility and protect individuals.

In April 1943 Meisinger was told to investigate all German journalists living in Tokyo – perhaps something he should have done before. He reported on twenty-three including Lily Abegg, and sent it through to Berlin. By August they had sent back a reply saying that no prejudicial or criminal information had been found on any of them except in four cases. Still on the defensive, Meisinger denounced several people as alleged spies to the Japanese. In addition to the industrialist Willy Rudolf Foerster, a journalist and a doctor were among his victims. Meisinger apparently worked with falsified evidence or confessions. One case was that of the journalist Karl Raimund Hofmeier. Meisinger falsified documents and persuaded the Japanese to arrested Hofmeier in 1942 as the alleged second Richard Sorge. After some months they handed him back to the German Embassy after they could find no evidence to back the claim. He was sent to Germany but on the way was executed.

Two years after his arrest Sorge was executed in 7 November 1943 but the German Embassy was not formally told of this until the following December, although Meisinger is said to have known earlier.

In the course of the following years Meisinger said he was able to pick up snippets of information unofficially. The Japanese painted a picture of a man more given to alcohol than newspaper work. They said that until 1941, they had no suspicions in spite of the fact that he had ‘intimate relations with many Japanese women.’ During that year the Japanese police began to investigate the activities of all foreigners. It was found that Sorge not only had very good relationships with the German Embassy but also with the office of Premier Konoye through Osaki-san. The Japanese woman with whom Sorge lived was used by him to establish relationships with many shady foreign characters in Tokyo. Their further investigation led to the discovery of the radio transmitter operated by Clausen and subsequently the code was broken. The Japanese authorities decided to allow Clausen to continue to operate in order to give the secret police time to determine the sources for the intelligence.

Meisinger in turn was later executed as a war criminal in Poland.

Key Sources:

HEARINGS ON AMERICAN ASPECTS OF THE RICHARD SORGE SPY CASE. (Based on testimony of Mitsusada Yoshikawa and Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby)

CIA Files

British Intelligence files

The Case of Richard Sorge” Secret Operations in the German Past in the 1950s Spy Fiction. Cornelious Partsch Monatshefte. Vol. 97, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 628-653 (26 pages) Published by: University of Wisconsin Press.

Mainichi Japan. August 18, 2018.

Various online sources.

Updates to this site are always made on Twitter @japanauthor

[…] A Nazi who drank there was the Butcher of Warsaw, the head of the Gestapo in Japan and China, one Josef Meisinger. He too socialised with Sorge. His story can be found here. […]