Once notation became formal practice in Europe, composers would experiment with folkloric bells for special effect. Familiar examples are in Bach cantatas and Mozart operas.

Beginning with the Romantics, bell textures became a resource at the piano.

The scampanatino (“like bells”) variation of Alkan’s Le Festin d’ Ésope has an upper ostinato descant that clashes with the lower voices:

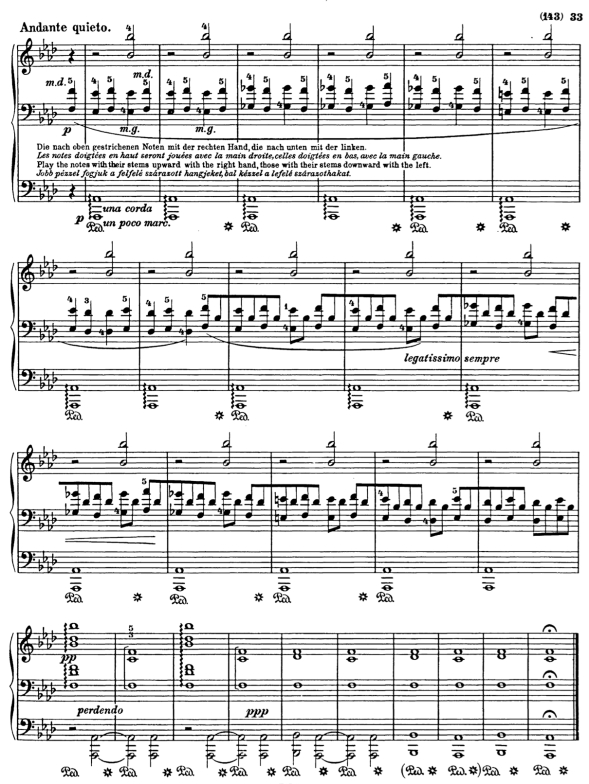

Liszt’s “Evening Bells” from his late suite Christmas Tree ends with an impressive foreshadowing of impressionism:

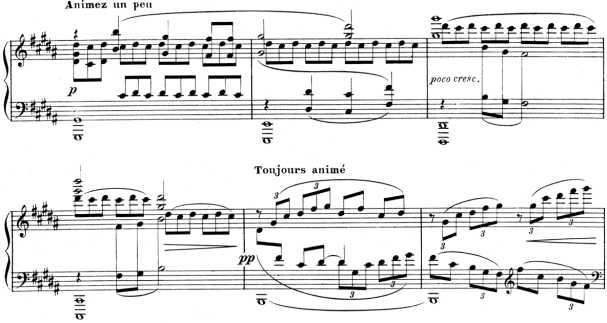

Debussy was deeply inspired by the gamelan, the Eastern orchestra comprised of tuned bells. “Pagodes” is a direct tribute:

Rachmaninoff loved his liturgical bells, for example in the climax of this Op. 39 Etude Tableaux:

Good public bells are specially tuned to bring out the sweet spots of their natural harmonic resonance. As Rachmaninoff makes clear, high register fourths and fifths at the piano are a natural approximation of bells.

—-

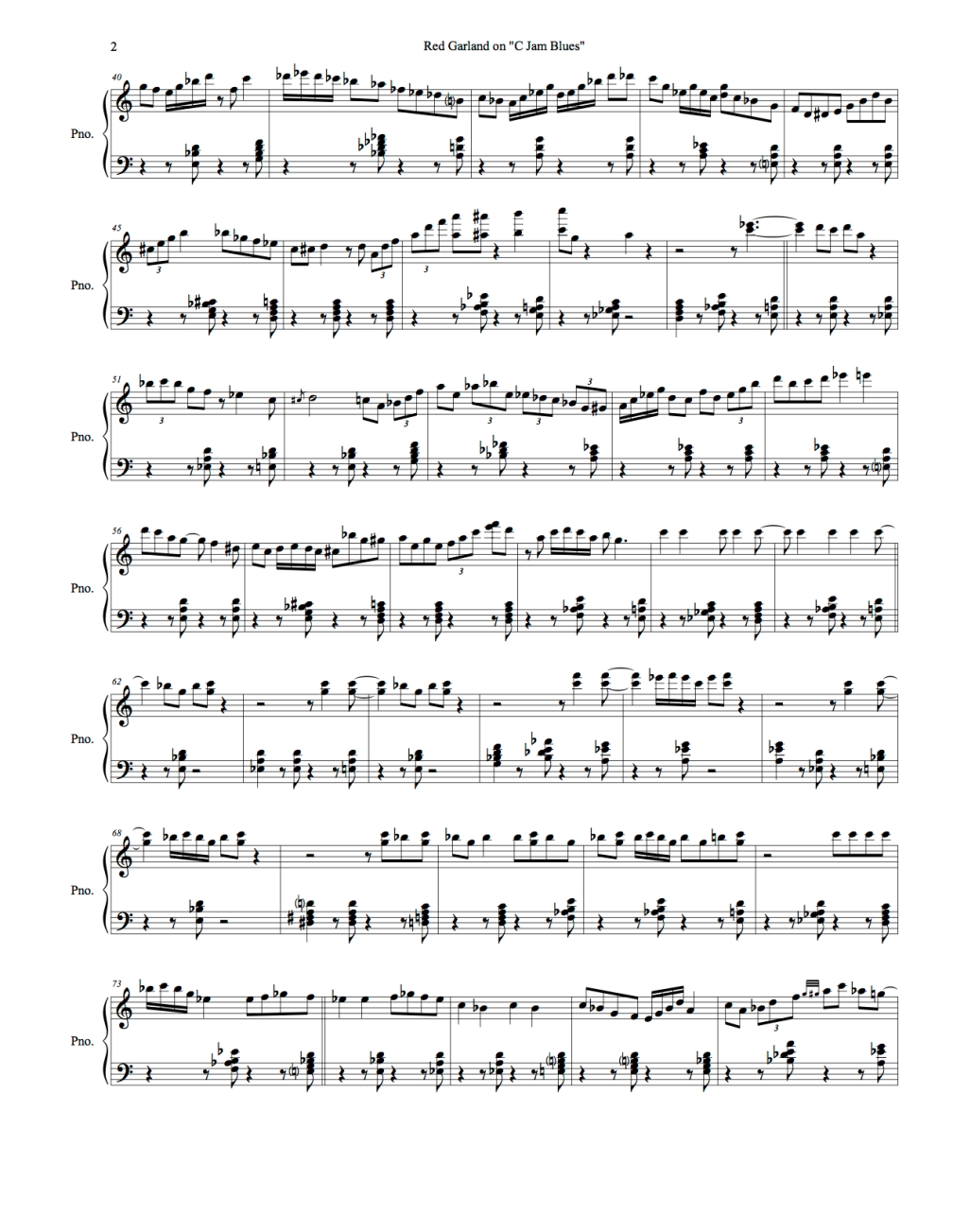

Red Garland was famous for his block chords. The right hand of Red’s block chords are usually a repetitive structure, an octave with a fifth in between. He uses the same structure when comping as well.

“If I Were a Bell” from Guys and Dolls is associated with Red Garland, and his orchestration of the concluding lyric from the 1956 trio recording demonstrates his classic sound:

To some, this harmonization lacks sophistication. Certainly the effect is unorthodox, with obviously “incorrect” pitches on top. However, Red’s left hand always accurately makes the changes — usually seventh and sixth chords, unmistakable as tension and release — thus ensuring that the essential harmonic function is never impaired. His high register bells simply thicken the sonority with agreeable dissonance.

It’s akin to the blues, but perhaps it is even older, more purely African in essence. There are small bells in African drum choirs: Indeed, the phrase “bell pattern” is important in modern academic assessments of classical African music.

When Red played with Miles Davis and John Coltrane, all the participants were merging African and European aesthetics. Although the harmonies are extremely sophisticated, harmony doesn’t drive the mechanism. Rhythm is in charge. With his bells in his right hand, Red intentionally sacrifices some harmony to the god of rhythm. After all, if Red were in a drum choir, he wouldn’t be able to play all those changes. Those vagrant bell overtones are a respectful gesture to percussive roots.

A European composer using bells at the piano wouldn’t be thinking of Africa, but they would be thinking of creating a theatrical effect. Indeed, denying the major-minor tonal system full authority is a subtle act of rebellion, which probably is part of why bells appealed to Alkan, Liszt, Debussy, and Rachmaninoff.

Admittedly, Red’s own comment in the liner notes to A Garland of Red is comparatively quotidian. Ira Gitler writes, “….Red also exhibits a locked hands chord style which he stumbled on one day while trying to phrase a certain idea. Becoming frustrated, he dropped his hands on the keyboard in despair and they fell into place to produce a sound he instantly liked.”

Speculation aside, Red Garland’s music is always dusky, always in the cracks, always a bit sad, always a bit cheerful. Always ringing the changes and always playing the blues.

—-

Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones created an immediate impact when they started playing with Miles Davis in 1955. Sonny Rollins got them right away for Tenor Madness; Art Pepper called his album simply Meets the Rhythm Section.

Bebop had been less about a dancing beat, so in a way the new group harked back to the swing era. Perhaps for the first time in small group jazz, Miles had a quintet that swung as hard as a big band.

The unit didn’t last that long but they played a lot of gigs and made a lot of records. 1956 was really their year: To fill out Miles’s Prestige contract the band tracked thirteen casually impeccable pieces on May 11 and thirteen even better pieces on October 26.

In between these marathons was the magnificent and highly organized Columbia debut ‘Round About Midnight. The recorded sound is better than the Prestige dates, and every note played by every musician has weight.

The Peacock Alley radio broadcasts from July are also well worth chasing down, showing the quintet burning bright in front of a black audience in Miles’s home town. Interestingly, while Miles never had Red solo on everything in a set, there usually was trio feature: at Peacock “A Foggy Day” and “Billy Boy” are without horns.

Although he was active on the scene with a variety of important mentors, there’s very little of Red captured on tape before the classic Miles quintet. On a 1952 live date with Charlie Parker at Storyville, Red shows he’s a perfect bebop pianist. Just before the classic quintet, The Musings of Miles has Red and Philly Joe with Oscar Pettiford. Musings is solid but not quite there yet: Paul Chambers was required and Red was still absorbing lessons from the leader.

Red himself said that he learned a tremendous amount from Miles. Unquestionably they worked closely together when crafting the band sound. There’s a famous Dennis Stock photo of Miles’s hands on top of Red’s in the studio during Milestones.

Miles taught two academies in particular: the Dizzy Gillespie academy and the Ahmad Jamal academy.

In the liner notes to The Musings of Miles, Davis says, “You can always learn something from Dizzy Gillespie.” Gillespie’s arrangements are all over the Miles Davis repertoire of the 1950’s: “Two Bass Hit,” “Salt Peanuts,” “Woody’n You,” “Tadd’s Delight.”

When Red and Philly Joe make hits together behind Miles or John Coltrane, they are Gillespie big band-derived.

Coltrane played with Gillespie as well, and several of the tracks from the albums All Mornin’ Long and Soul Junction (a day’s work for Red and Trane with Donald Byrd, George Joyner and Art Taylor on November 15, 1957) are Gillespie big band repertoire staples: “Birk’s Works,” “Our Delight,” and “Woody’n You.” The later two pieces have even more of the Gillespie band material than versions recorded with Miles.

Red’s album Manteca features Gillespie’s latin anthem with the help of Ray Barretto. Early on in his solo, Red plays Diz’s familiar repeated note triplet riff exactly.

Ahmad Jamal was the other source of mood and repertoire. For Jamal, space was key: letting the rhythm section breathe, leaving stuff out. Emphasizing the song, not the bebop.

The 1958 trio “Billy Boy” from Milestones is directly inspired by Jamal’s arrangement. (Naturally, Jamal’s version of “Billy Boy” doesn’t have bells in the right hand, Jamal’s intervals are “normal.”)

It’s easy to hear the Garland/P.C./Philly Joe “Billy Boy” as Jamal + Gillespie big band. Coolness and fire together, a meeting of the the best from both traditions. Even those who don’t consider Red Garland their favorite pianist admire “Billy Boy,” a landmark performance featuring a spectacular drum clinic from Philly Joe Jones.

Jamal’s pedaled, on the beat, luminous harmony for ballads was also important to Miles and Red. On the studio tape of “You’re My Everything,” Red begins the intro with some runs. Miles stops the take and rasps, “Block chords, Red.” The pianist then sets up a more song-oriented atmosphere, the kind of atmosphere found on any Jamal record.

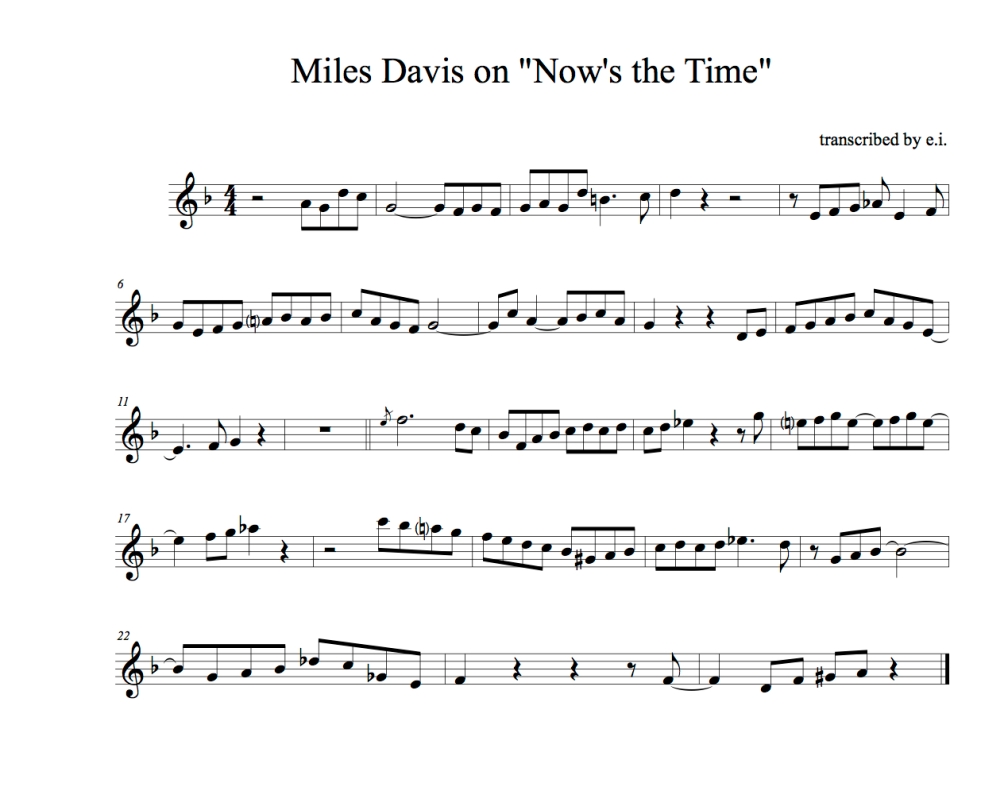

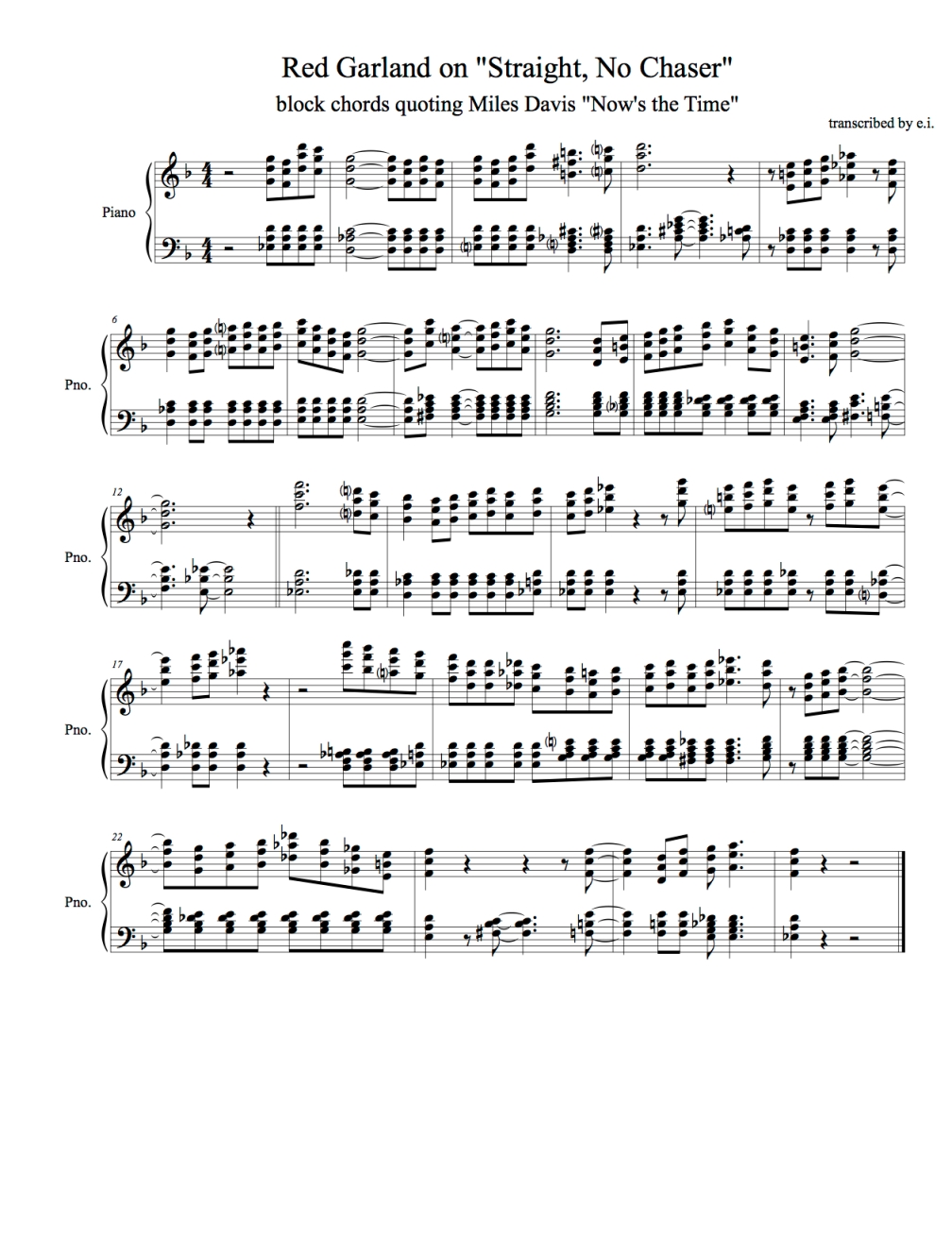

Red appreciated the school of Miles Davis. In an innovative tribute, Red plays his employer’s “Now’s the Time” improvisation (recorded with Charlie Parker when Miles was 19) on “Straight No Chaser” from Milestones. Miles’s solo is tailor-made for Red because the original improvisation is melodic and diatonic: Red’s bells are foreshadowed by Miles’s “wrong” major sevenths.

—

Several harmonic cross-relationships are authenticated by Red’s bells. The most obvious are the major seventh on the dominant and the natural fifth on the diminished.

Those cross-relationships are perfect for soloists who liked access to the whole complement of all twelve pitches: Miles through patient improvised melodic discovery, Coltrane through speed and chord substitution.

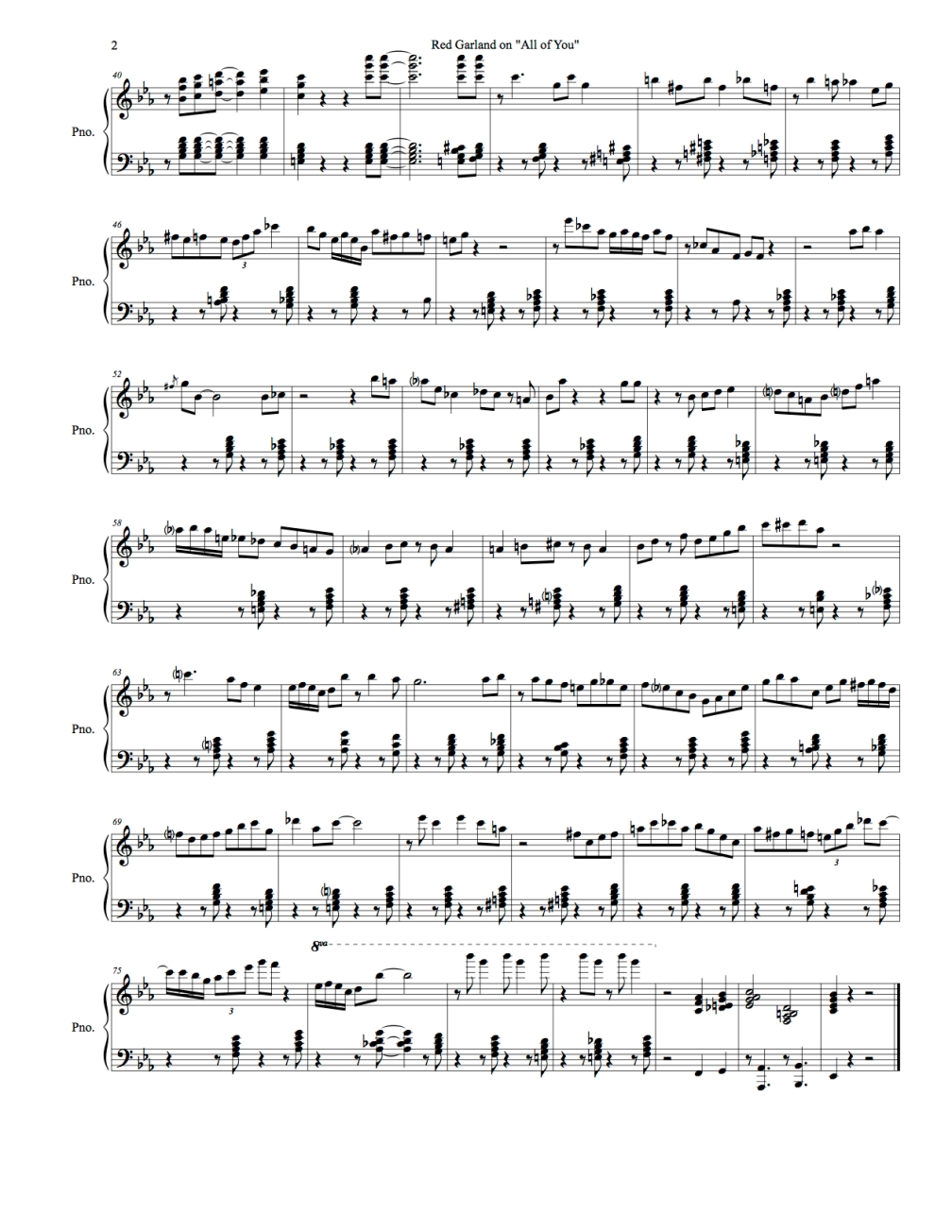

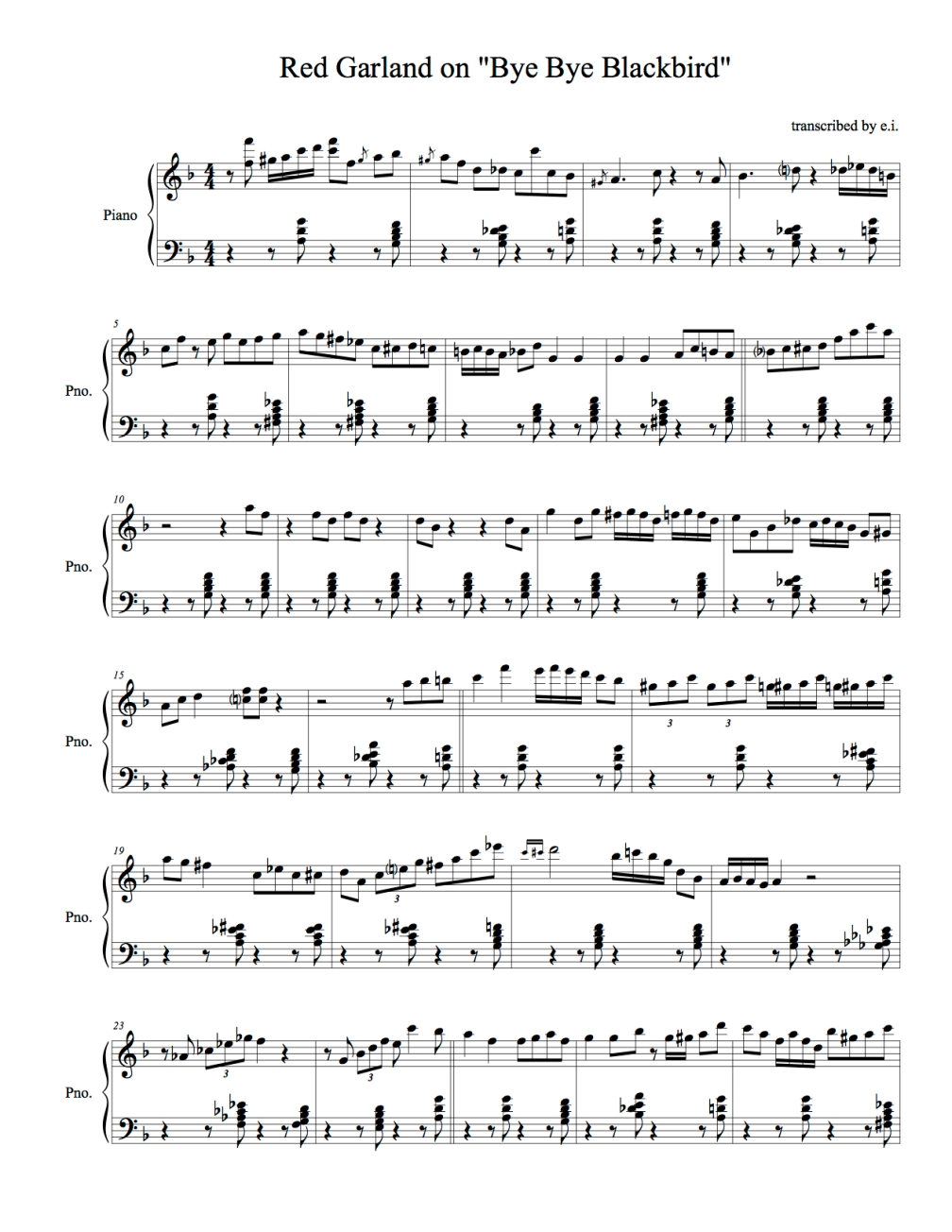

Those different approaches are displayed on “All of You” and “Bye, Bye Blackbird” from ‘Round About Midnight. Both tunes are now familiar standards thanks to this album, yet there’s no certain agreement on exactly what the changes are when at a jam session today. That obscurity is at least partially due to Red Garland’s mysterious performance. While comping, Red refuses to lock anything down, offering half-diminished, minor seventh, and dominant sonorities in simultaneous fashion. Whatever happens is fine, as long as it is swinging.

Red’s bells give not just space for the soloists, but space for the bass. Paul Chambers is free to make up his own patterns, follow independent motives and give any inversion of the spontaneous harmony.

Red comps for himself just like for the soloists. Red played alto saxophone first, which must be part of why his bluesy bebop lines in the right do not need to interact with the harmony in the left. It’s not obvious at all — blink and you’ll miss it — but my god, are the right and left ever in different spheres in terms of pitch collections. Those unlikely cross relationships are an essential part of that Red Garland sound.

Again, the defining element is rhythm. Frequently Red’s left hand pattern is mostly upbeats of 1 and 3. It’s like he’s part of a drum choir that requires those upbeats for the clave “sentence” to work. The swing generated by Red, P.C., and Philly Joe together is thanks to the subtle, accurate, yet still casual combination of phrases that answer and complete each other.

That repetitive left hand helps Red focus on spinning the bop and blues in the right, just like the left hand of a stride or boogie-woogie pianist. Once the lower mechanism is in gear, the higher elaboration can be threaded with care and heat.

Before Red was a musician, he was a boxer: He had 35 professional fights and opposed Sugar Ray Robinson for an exhibition match in the Army. Those upbeats in his left could easily be called “jabs.” He also really “hits” with his right on those bebop improvisations, ducking and weaving with perfect accentuation. Red has a pretty touch — a gorgeous touch, really — but the fact that he was a boxer before settling on a career in music makes a lot of sense.

—-

As noted above, Jamal’s song choices were important for Miles, but Red himself was also an important source of repertoire. Red knew all the tunes, bringing several pieces to Miles Davis’s or John Coltrane’s attention, including “If I Was a Bell.” In his autobiography, Miles declares, “Red Garland used to tell me what ballads he wanted to play, not the other way around.”

From 1956 to 1962 Red turned out almost 20 albums as a leader, mostly trio, stocked with all manner of standards. Serious, corny, sentimental, chirpy, bluesy, whatever! A tune was a tune was a tune.

It must have been so easy for him, in a way: Grab a melody from the radio or a songbook, add swing and blues, decorate with bells, and roll tape.

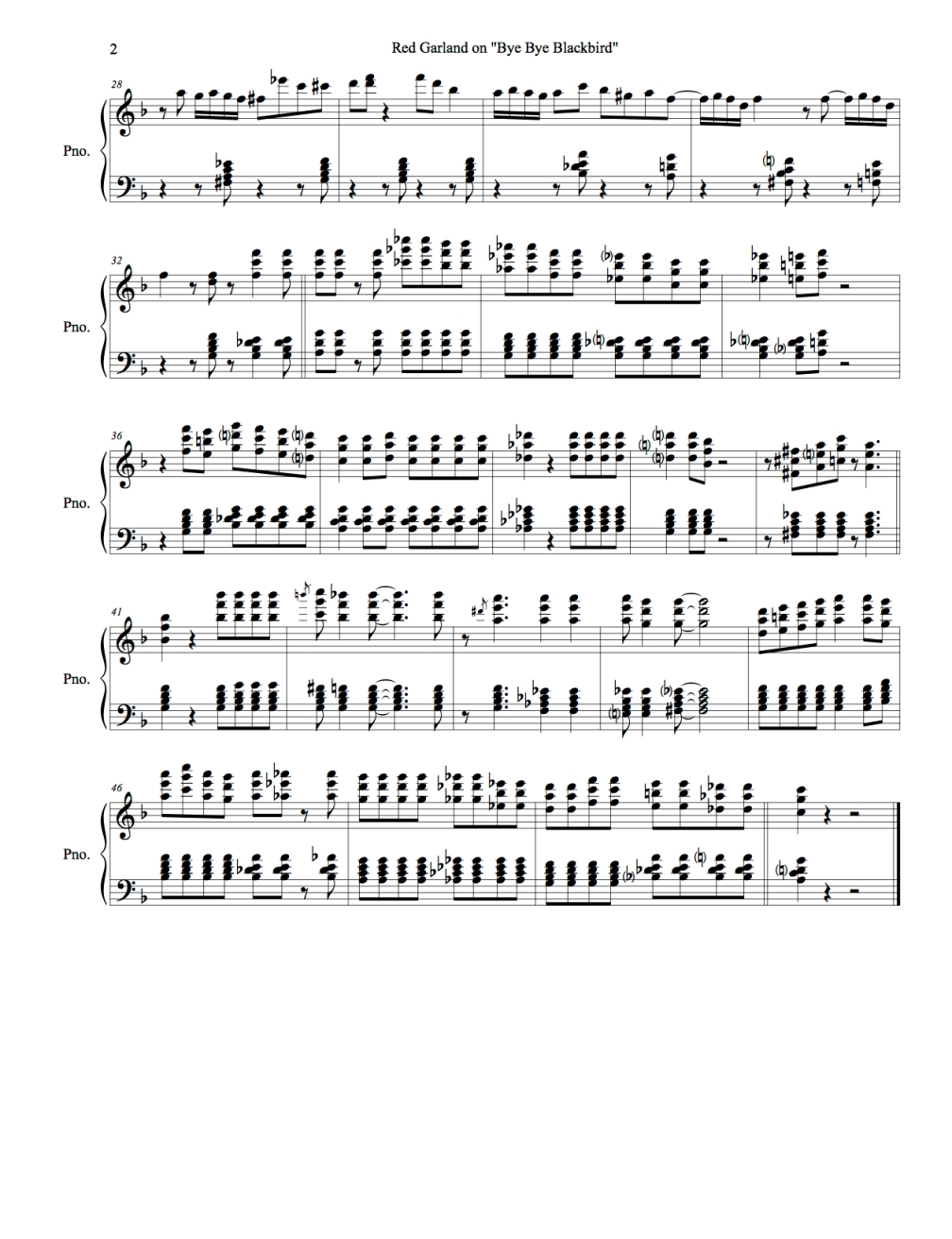

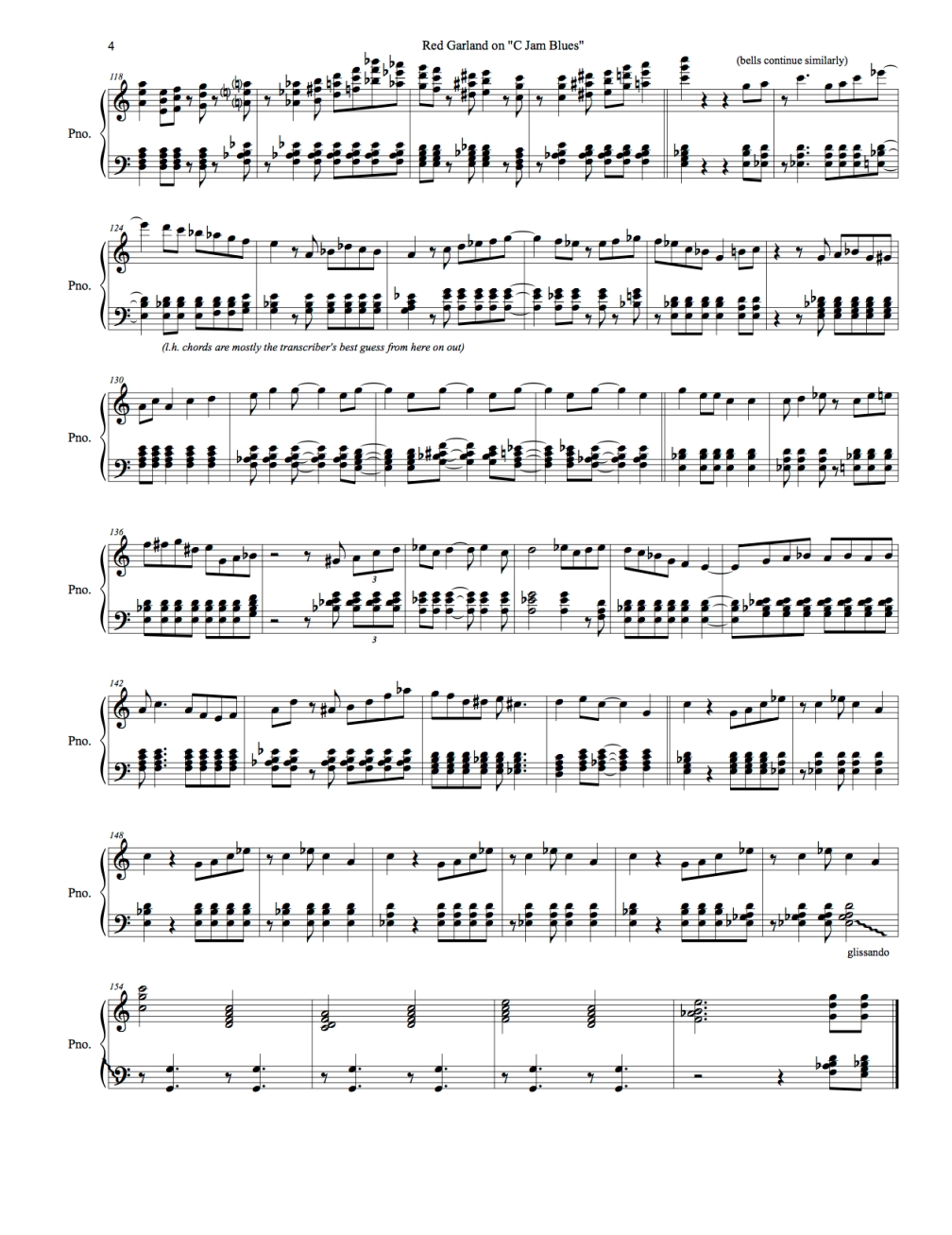

If you aren’t Duke Ellington, programming “C Jam Blues” is not usually a good idea. For the opening track of Groovy, Red shows true mastery, orchestrating the tune perfectly before spinning out a long blues effusion. Damn, this is so swinging! Paul Chambers is on fire. Art Taylor is the security guard, giving a nice centered beat for PC to work against.

Coltrane liked this trio as well: he made three albums with them and counted Soultrane as a personal favorite LP. In fact, with the exception of three tracks with Mal Waldron, Red is the only pianist Trane used for any of the saxophonist’s many sessions for Prestige as a leader.

Trane was really getting his velocity together and Red’s comping is bright and unfazed during the fastest tempos of “Lover” and “Russian Lullaby” (Trane joked to Bob Weinstock that it was called “Rushin’ Lullaby”), not to mention the truly absurd prolonged double-time frenzy of “Sweet Sapphire Blues.” (The tenor solo is mostly sixteenth notes at slightly faster than quarter note = 200 for over four solid minutes.)

However, when Coltrane branched out to recording complex originals for Blue Note or Atlantic he hired Kenny Drew or Tommy Flanagan. This may be just because of the producer: Red is not on a single Blue Note LP, perhaps because Prestige was pushing Red so hard as a leader. It is also possible that Coltrane thought that the very hard changes of “Moment’s Notice” or “Giant Steps” needed something that Red couldn’t give. (In a related topic, there’s also a strong possibility Coltrane didn’t record many originals for Prestige because Weinstock and company insisted on keeping the publishing for their artists’s original compositions.)

The music wasn’t just getting faster and more complicated with Coltrane’s changes; it was simultaneously slowing down and staying on the same chord. Red comps perfectly on the first well-known modal tune “Milestones,” but that piece is fairly contained and the comping stays close to the melody. It’s hard to imagine Red playing the comparatively wide open “So What.” Indeed, as far as I know, there’s not a single recorded example of Red taking a modal solo.

“Invitation” with Wilbur Harden is the Prestige track that comes closest to something Trane might have played in the future modal-meets-standard style of “Out of This World.” While Paul Chambers foreshadows Jimmy Garrison, Red is comparatively uncomfortable with the vast expanses of unbudging minor. As with “Milestones,” there’s no piano solo.

In The Great Jazz Pianists, there’s an interesting exchange with Len Lyons:

Len Lyons: What do you think of jazz/rock or fusion music? Do you like it?

Red Garland: Sometimes, except that it always sounds like it was played on one chord. It doesn’t move around enough for me harmonically.

LL: Coltrane used to play on one chord too.

RG: I know, and I got down on him about it.

—-

After the time with Miles, Coltrane, and Paul Chambers, the best of Red’s albums is arguably Red Garland at the Prelude with what could have been a hell of working trio featuring Philadelphians Jimmy Rowser and Specs Wright. They are swinging hard in a supper club in Harlem in 1959 and it’s kind of a perfect document overall.

For whatever reasons there was no momentum towards a serious career as a leader. A couple years later Red went back home to Texas, leaving behind some of the most soulful bells ever heard on some of the most canonical jazz records ever made.

Red Garland’s chord at the top of John Coltrane’s “By the Numbers”:

—-

Bonus bells:

Ding: On Milestones, the trumpeter himself plays piano on “Sid’s Ahead.” The legend has it that Red was angry at not getting enough solo space on the album and left the studio.

Maybe that’s true, but the balance of solos on the album seems ideal, with Red’s bebop fury on “Billy Boy” and theatrical bells on “Straight No Chaser” compensating for no solo action on side A. I mean, with three of the greatest horn soloists playing their best, do you really need a lot of piano solos? Indeed, Miles himself doesn’t blow on “Two Bass Hit,” sensibly leaving the turf to Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley.

On the original “Now’s the Time,” Dizzy Gillespie sits in on piano and offers some terrific comping. Could this be another reason Miles plays on “Sid’s Ahead,” a second reference to Miles’s first great recorded solo?

Or perhaps there weren’t any extramusical factors: For an album of mostly blues, the leader might have just really wanted something different on one tune. The final effect is similar to Wynton Kelly sitting in on “Freddie Freeloader” on Kind of Blue.

Ding: What I’ve heard of Red’s return albums from the 1970’s are solid, he still has the magic, but in general he’s a bit slower and the rhythm sections are less of a perfect fit. Philly Joe was in a similar place: The recent issue of Red and Philly Joe live at the Keystone Korner with Leroy Vinnegar is a compelling enough listen for serious jazz fans but no one could argue it is what it was in 1956. However, the packaging from Resonance Records is just wonderful, with inspiring interviews and loving notes by Ira Gitler, Benny Green, and Kenny Washington, plus a reprint of Doug Ramsey’s important interview/profile from the 1970’s.

Ding: “All of You” turned out to be a particularly interesting afternoon’s exploration. From 1954, it is the last Cole Porter song to be taken up by jazz musicians. In Eb, Cole wrote the first chord as Ab major over the tonic, a chord generally ignored by jazz musicians who play Ab minor or F half-diminished. Ahmad Jamal got to it before Miles, but played it in C with the first chord hinting at Db, a move expanded upon by Bill Evans in his impressionistic version also in C. (Scott LaFaro seems like a likely collaborator for the creation of unusual pedal points in Bill’s remarkable reharmonization.) The many live Miles Davis versions with either Wynton Kelly and Herbie Hancock show how the greatest rhythm sections evolve from gig to gig. Each crew has their own post-Dizzy collection of hits and riffs.

McCoy Tyner did a 1963 jam on “All of You” with Bob Cranshaw and Mickey Roker that naturally points up McCoy’s deep study of Red Garland.

Ding: Indeed, the legacy of Red’s vital comping for Coltrane lived on in McCoy Tyner, whose quartal harmony and percussive interlocking comping is a kind of like an updated set of bells.

Ding: “All of You” in any Miles Davis version has an extended turnback section of “III VI II V” for every soloist. The same event occurs in “If I Were a Bell.” Perhaps the turnback works so well because the songs are ABAC, not AABA?

Both arrangements also conclude at the very end with a surprise minor chord, a special effect that seems connected to bebop. I suspect these are Miles Davis touches, but it’s true that Red plays the same arrangement of “If I Were a Bell” with his trio, albeit recorded after the quintet version. (Strangely, the trio version doesn’t end the first half of the melody in A major, to me a terrific detail.)

There’s something very Afro-African about both the turnback and the minor ending, elements that help curb any corny or overly Caucasian associations inherent in these frankly rather goofy standards.

Ding: One reason I’ve spent so much time in the recent decade contemplating Red’s importance is Billy Hart, as Red Garland is a cornerstone of Billy’s teaching. On a related topic, Billy likes to quote something Bob Brookmeyer told him: “The more experienced a drummer is, the more upbeats he plays.”

Billy also repeatedly makes the point about the influences of Dizzy Gillespie and Ahmad Jamal on Miles Davis. (This is not Billy’s original idea, of course, Miles himself talked about it.)

Anyway, Billy is the undeniable godfather to this essay, although that shouldn’t suggest that he would sign off on all my speculations.

Ben Street talks a lot about Red as well.

Ding: The topic of “rootless voicings” in jazz academia tends to focus on Bill Evans. (Just one example: Andy Laverne’s essay in Keyboard Magazine.)

Bill was a master of this style, but before Bill released any significant records, Red consecrated the approach of rootless voicings on all those important and widely-listened albums with Miles and Coltrane.

It’s wildly different than Bud Powell, Thelonious Monk, or Horace Silver, giving much more space and responsibility to the bass. It very quickly became the way to play jazz piano.

Not just Bill, but also Wynton Kelly and Herbie Hancock seemingly had to use that approach following Red in the Miles Davis piano chair. (In a way, McCoy Tyner’s more bass-heavy approach was a throwback to Bud and Monk, although of course McCoy played plenty of rootless voicings also.)

However, Hal Galper (among others) would argue that Ahmad Jamal should really get the main credit for “rootless voicings.” There’s a relevant page at Galper’s website. I’ve just spent some time listening to Ahmad’s fabulous 1952 music (the tracks that impressed Miles so much) and there’s no doubt rootless voicings are there. However, Ahmad plays in a lot of ways, even within a single chorus, and rarely features rootless voicings for a long stretch. Obviously Ahmad wasn’t a band pianist like Red, either: There’s no example of Ahmad comping for anybody in the 1950’s with rootless voicings like Red did for Miles and Coltrane.

Bill highlights rootless voicings more than Ahmad by constantly playing them, and highlights them more than Red by playing them in a more sustained fashion. He was also fairly consistent in his organization, which makes his harmony easy to teach. A table of Bill Evans voicings almost writes itself.

Red is harder to analyze, water down, and hand to a student, especially since Red’s hands don’t play from the same scale. (Bill’s hands usually do play in the same scale, except for rarities like the avant-garde “Peace Piece” or places where he is most indebted to Lennie Tristano.)

Added-note harmony in jazz goes back at least to Duke Ellington and Art Tatum, and presumably all significant pianists of the early 50’s were considering how to play more freely with the bass before the concept was permanently brought to the forefront by Ahmad, Red and Bill. Billy Taylor was a name once mentioned to me as important in this transition. Al Haig also could be relevant.

The point of all this is simply that when “rootless voicings” are mentioned in a basic jazz text the names of Ahmad Jamal and Red Garland should be cited as often as Bill Evans. While I’m trying to challenge conventional wisdom, let me also note the harmonic and rhythmic interplay of Red Garland and Paul Chambers is worthy of as much interest as Bill Evans and Scott LaFaro.

Ding: When Red doesn’t play the upbeat rootless voicings with bass and drums, it is usually growling sustained sevenths and fifths like his important mentor Bud Powell. This can be heard throughout Bird at Storyville. (Which is an argument for Jamal doing it first and influencing Red.)

On the pretty solo discs Red Alone and Alone With the Blues the left hand connects to stride, Nat Cole, Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, and various blues pianists. Both hands play the same harmony, with the bells generally less in evidence.

The piano improvisation on “Oleo” at Peacock Alley has rather bizarre and uncomfortable low single-note upbeats in Red’s left. Perhaps that’s why Red omits his left entirely in the slightly later studio version of “Oleo.”

On the other hand, maybe Miles Davis told him to leave it out? We know that Miles told Herbie to leave out his left for the uptempo solos on Miles Smiles…

Whoever thought of it, leaving out the left encourages both Red and Herbie to play lower in the right, giving their lines an intriguing Tristano-ish cast.

Ding: I’ve brought up Red to several musicians on DTM interviews, often asking them to compare Red to Wynton Kelly. There’s no right answer, both pianists are wonderful, but it does seem like everyone has an opinion.

CW: When I first got here, I met Red Garland: I introduced myself to him because he was from Dallas. His father lived two blocks from me. So I said, “Hi, Red, I’m Cedar from Dallas. I know your father.” And Red was an instant buddy. He was standing next to Miles Davis at the bar of the Cafe Bohemia. He said, “Oh man, Miles, this is my man – what’s your name – Cedar? – from Dallas.” And Miles said, “You know J.K. Miller?” Now that just floored me – that Miles Davis knew my band director. I almost fainted. I had to count to ten. So I said, “Wow, I must’ve come to the right city. They know my band director here.” Then Fathead explained to me that he probably passed through East Saint Louis – or wherever Miles lived – with one of these bands. And Miles was hungry like I was, I guess, to hear trumpet sections and things like that.

EI: Did Red show you anything at the piano?

CW: No, he was not that type. His chords were totally…non-institutional, if I might coin a phrase. Like “Billy Boy.” You know how rich those chords are. That’s him – that’s just unanalyzable. To me, anyway.

EI: Well, it’s true they have a lot of non-normal notes in them.

CW: Yeah, they sounded right to me. They started sounding normal to me.

EI: Those beautiful fifths – stuff like bell tones in there to give them an extra ring.

CW: Oh, I see, well I never looked at it like that. Philly Joe told me when they played one week at a place here, the first night or two he was figuring out how to play the tunes – maybe with some really wrong notes in the chords – and by the end it was all together.

EI: Interesting – because on the records he always sounds perfect.

CW: Oh yeah – he’s not gonna let himself sound less than perfect on a record. I just meant in a live situation.

He wasn’t that intrigued with New York after he left Miles, and went back to Texas. You would have to send for him. If the gig started on Tuesday, though, he would come in on a Monday, because he would always go down to the Vanguard and listen to that orchestra. He knew all those arrangements. He could sing them all, which gives you insight into his style of musicality. Miles used to love to give him at least one feature on the set, you know, as a trio.

EI: Well, let’s go back to some word association: Red Garland.

FH: Laid back. I mean, I always think of him—whether he was or not—I think of him as one of the ultimate junkie pianists. Everything’s so laid back. When I listen back now, the block chords, they don’t really sound very good to me. They did back when I was first learning, and of course, I have I don’t know how many dozens of Miles albums, so Red Garland is on all of those Prestige albums.

EI: Contrast Wynton Kelly and Red Garland.

FH: I always liked Wynton more. I mean, I think Wynton had what I call happy time, you know, just made me feel good. It had a little “pop” to it. Not that Red didn’t really play great. I mean, look at “Billiy Boy.” There are a lot of great Red Garland tracks. But Wynton, there was a directness – not easy, but kind of an ease, a simplicity. And I think, you know, certainly Herbie Hancock, as far as his time, owes a lot to Red Garland, as he does to Bill Evans.

GC: ….And then I fell in love with Wynton Kelly’s playing… I never got to see him play, but I was certainly strongly affected by his music.

EI: Contrast him with Red Garland.

GC: Oh, ok. Well Red… I didn’t get the same feeling from Red. I mean, Red, I don’t know how to describe him, I didn’t listen to him on his own a whole lot, but I listened to him with Miles a lot. I just thought Wynton swung to death. Red, what I remember about Red was his left hand, that left an impression on me, that insistent thing, you know. But I thought for me, Wynton was the guy.

Red seems to be the guy… I keep trying to say something, but then I think of an exception, thinking “No, that can’t be it!” [laughs] Red would make it swing, and somehow, Wynton would let it swing. I think, but I’m sure I’m wrong, Red sometimes would attack the piano more than Wynton, although Wynton played hard. Although there’s an exception because of how Red plays “My Funny Valentine,” I really love that, it was really tender.

I just got the feeling that Wynton had a sense of freedom. I spent more time listening to Wynton, definitely.

EI: Contrast Wynton Kelly and Red Garland for me.

JM: Well, first of all, they both swung. Wynton Kelly is one of the hardest swinging guys; I mean he would play an eighth note line and the hair on the back of my neck stood up. It’s just killing. And they both had a rhythmic thing they did in their comping behind Miles. I think I dug Wynton a little more, he might have had a little harder touch, although you never know, a lot of Red’s recordings were done at Rudy’s studio, and it’s almost like everyone almost sounded the same on that piano. I was a fan of Rudy’s sound until the first time I ever recorded out there and then I realized, “Man, I was screaming on the upper register,” and it just comes out like [Jim sings tik-i-tik-i-tik-i], he’d take all the highs off the sound.

Anyway, Red Garland seemed to have a little bit of a lighter touch. And of course, what he called the block chord thing, the octave with the 5th and the left hand stuff that was his signature sound.

I got to know Red a little bit in the later 70’s. Dexter Gordon was kind of the poster guy for bringing back some of the older players wherever they had gone, and Red Garland played the Vanguard. By that time I think Red was playing 5 nights a week in a club in Dallas and lived in a one-room apartment. And so he came up to the Vanguard and this guy who had been a neighbor of mine knew Red from the Dallas days so we hung out with him one night in his hotel room and talked with him, and he was telling all kinds of stories. And I’d go to hear Red at the Vanguard. His closing theme was “Going Home” from the Dvorak symphony. He’d play it in the key of F so the melody has a D at the end [Jim sings “dum dum dum DEE”] but in the left hand he’s playing the flat-9, the D-flat [dum dum dum duh]. And I’d sit there and think, “Wait a minute, you’re not supposed to do that.” Then realized, “But that sounds like Red Garland.” That tension in there, you know?

This is stuff I’ve learned from seeing some of Thad’s scores and other things of people from that time. There were rules that had been developed in Jazz education, but these guys didn’t have these rules when they were making their music. There were just certain tensions they used, and not only did they work, but they became part of what made them sound that way.

So Red had those little things, but I think it’s because of hearing Wynton comp with Jimmy Cobb and Paul Chambers that I was just attracted to that a little more, plus he swung so hard.

Wynton Marsalis didn’t appreciate Red’s comping on “Blues by Five.” “H’mm: again, piano players are always playing like the snare drum, though,” was his dismissive comment. I can’t agree with this, although it explains something about how Marsalis looks for greater varieties of texture from his pianists (something I do agree with).

The last word comes from Masabumi Kikuchi:

EI: Who else did you check out when young? Red Garland and Wynton Kelly?

MK: Yeah. Most people kind of liked Wynton Kelly a bit more than Red Garland. As for me, I liked Red Garland. It’s impossible or almost impossible to play the piano like him, if you don’t know the piano well. His playing taught me a lot about how to play the piano. Things like phrasing among other things. He was a boxer, I think that influenced his approach.

EI: He’s got those notes in the middle, those dissonant notes in his chords, right?

MK: Yeah. Everything in his playing shows how every note has some kind of meaning…a very special meaning, you know? So Red Garland had a big influence on my piano playing. A touch of being more beautiful, not to just be stronger. I understand why Miles hired him.

EI: Coltrane loved him too. He was on a lot of Coltrane’s records.

MK: I think he’s a master of playing the background for melody players. He has a special gift I think.

EI: I think so too. I also prefer Red over Wynton Kelly although a lot of people like Wynton Kelly more.

MK: Yeah…Wynton Kelly is very catchy right?

EI: Yeah, very slick.

MK: Slick! I like him. But Red Garland is more like a piano master, right?

EI: I agree, yeah.