Hakuin & the Revival of Rinzai

“If you forget yourself, you become the universe.” – Hakuin

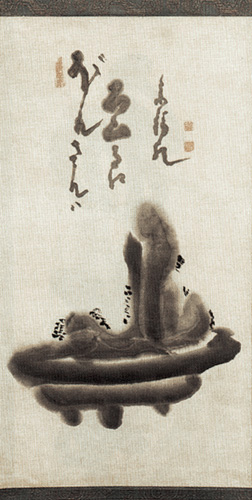

Hakuin Ekaku (1686 – 1769) is one of the two most important patriarchs of Japanese Zen, along with Dogen, the founder of the Soto school. Hakuin did not found the Rinzai school (the House of Linji) in Japan, coming along five hundred years after Eisai, who met Dogen but died the next year, firmly established Rinzai in Japan in 1187 after traveling to get teachings from China. Hakuin did however revitalize Rinzai so thoroughly that his koan system remains the core of Rinzai practice and today all schools of Rinzai Zen trace themselves back to him. He was also an accomplished artist, producing many classic paintings and works of calligraphy.

Rinzai received enthusiastic support from the rising samurai class of the Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333), as Eisai founded a new branch in Japan, parallel with the House of Linji’s earlier popularity with local warlords in China in the period between the Tang and Song empires. A warring states period once again produces support for new, irreverent and divergent points of view, which was not invisible to scholars of China and Japan of the time. Then in the following Muromachi period (1336 – 1573) Rinzai Zen was the favored sect and administered by the Shogun.

This was the time of Bassui (1327 – 1387), the Rinzai master who was obsessed with the idea of the ungraspable self as a young child, who refused to wear traditional robes or recite sutras, but rather spent all his time as a monk in meditation. Bassui taught that many monks are attached to permanence and stability who fall too far on the side of ritual and dogma, but there are also too many monks who are attached to impermanence and freedom who fall too far on the side of anarchy and irreverence. This is very similar to Nietzsche’s ideas of Apollonian and Dionysian sides of humanity and the tightrope walker, which we will cover in the final lecture. This was also the period of Ikkyu (1394 – 1481), who became enlightened while watching and listening to a troop of blind musicians after studying case 49 of the Gateless Gate. Ikkyu would drink excessively, behave in terrible ways, considered sex in brothels a sort of Zen practice, and had a long love affair with the blind geisha Mori, a renowned singer. He was one of the most innovative flute players of the time, and influenced calligraphy and the tea ceremony.

In the Tokugawa period (1600 – 1868) of Hakuin, Rinzai was in decline, which is why he traveled far and wide as a young monk seeking a teacher of authentic Zen as Dogen did, contemplating Zhaozhou’s “Nothing” and the dog, the first case of the Gateless Gate. Legend has it that while meditating in one temple there was an earthquake, and everyone ran outside in fear, but not Hakuin, who remained seated. After much fruitless searching, he turned up at the place of the hermit Dokyo, the Old Man of Shoju, who was famous for the his depth of his understanding as well as his practice of meditation in graveyards surrounded by hungry, howling wolves.

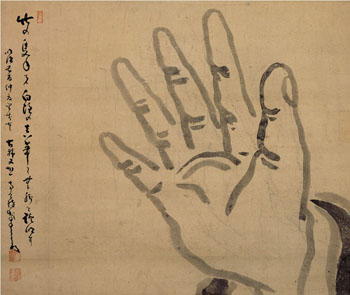

Hakuin wrote what he thought was a superb verse to demonstrate his own understanding, which Dokyo crumpled and tossed without reading, extended his hand to Hakuin, and asked him, “Learning aside, what have you seen?” Hakuin said, “If I’d seen anything I could present to you, I’d cough it up,” and he pretended to vomit into Dokyo’s open hand. Dokyo asked him, “How do you understand Zhaozhou’s Nothing?” Hakuin confidently stated, “In Zhaozhou’s Nothing there is nowhere to put your hands or feet.” Dokyo reached out, grabbed Hakuin by the nose and gave a twist, just as Mazu did to Baizhang, laughed and said, “I found somewhere to put my hands and feet!” Hakuin admitted defeat and Dokyo agreed to teach him, assigning him other koans to study. Asked why by Dokyo why he became a monk, Hakuin told him that when his devout Pure Land Buddhist mother took him to a sermon on the eight hot hells, he became terrified of hell as a child. Dokyo laughed and said, “You are such a self-centered little rascal!”

After eight months of studying several koans with Dokyo, one at a time, Hakuin considered himself to have received Dokyo’s dharma transmission and left to complete his understanding on his own. After many more years of study he experienced tremendous enlightenment, which he later taught came in the three stages of Great Doubt, Great Death, and Great Joy. First he experienced a period of anxiety, followed by a period of stillness, followed by a return to life with an abundance of happiness and strength. He sought a teacher to confirm he had attained a great awakening (kensho), but found no teachers who had experienced great enlightenment as he had himself, no one who could understand and confirm his understanding.

He returned to Shoinji temple where he had first been ordained a monk and was made head priest, adopting the name Hakuin, “concealed in white” like mountains in fog. Later he had another great awakening while reading the Lotus Sutra, a text he had rejected as false in his younger years, realizing that the true meaning of enlightenment is found in the bodhisattva path, in doing things for others rather than for the self. Hakuin lectured on the Blue Cliff Record 14 times in the period of 30 years he was head priest, and said he got something new out of it every time.

Unlike Dogen, who taught that the best way to enlightenment is seated meditation, Hakuin taught that the best way to enlightenment is contemplating one koan at a time, and over his years of teaching students he created a system that Rinzai still uses today. The pressure and tension of struggling with the confusion of a koan case is the “Great Doubt” that produces a powerful awakening. Hakuin classified koans into five types. First are koans that first introduce us to the fundamental awakened perspective. Second are koans that help us understand aspects of this awakened perspective. Third are koans that show how the old masters of the tradition understood things. Fourth are the difficult koans for cutting off attachment to how much awakening we have attained by this point. Fifth are the following five verses, which Hakuin taught was the final door to universal wisdom.

In the third watch of the night

Before the moon appears,

No wonder when we meet

There is no recognition!

Still cherished in my heart

Is the beauty of earlier days.

A sleepy-eyed grandma

Encounters herself in an old mirror.

Clearly she sees a face,

But it doesn’t resemble her at all.

Too bad, with a muddled head,

She tries to recognize her reflection!

Within nothingness there is a path

Leading away from the dusts of the world.

Even if you observe the taboo

On the present emperor’s name,

You will surpass that eloquent one of yore

Who silenced every tongue.

When two blades cross points,

There’s no need to withdraw.

The master swordsman

Is like the lotus blooming in the fire.

Such a man has in and of himself

A heaven-soaring spirit.

Who dares to equal him

Who falls into neither being nor non-being!

All men want to leave

The current of ordinary life,

But he, after all, comes back

To sit among the coals and ashes.