The growth of modern streaming platforms and alternative media has ushered in a golden age for documentary films, series, and short-form projects. Editors working on scripted versus unscripted projects find similarities, but also major differences between these two film genres.

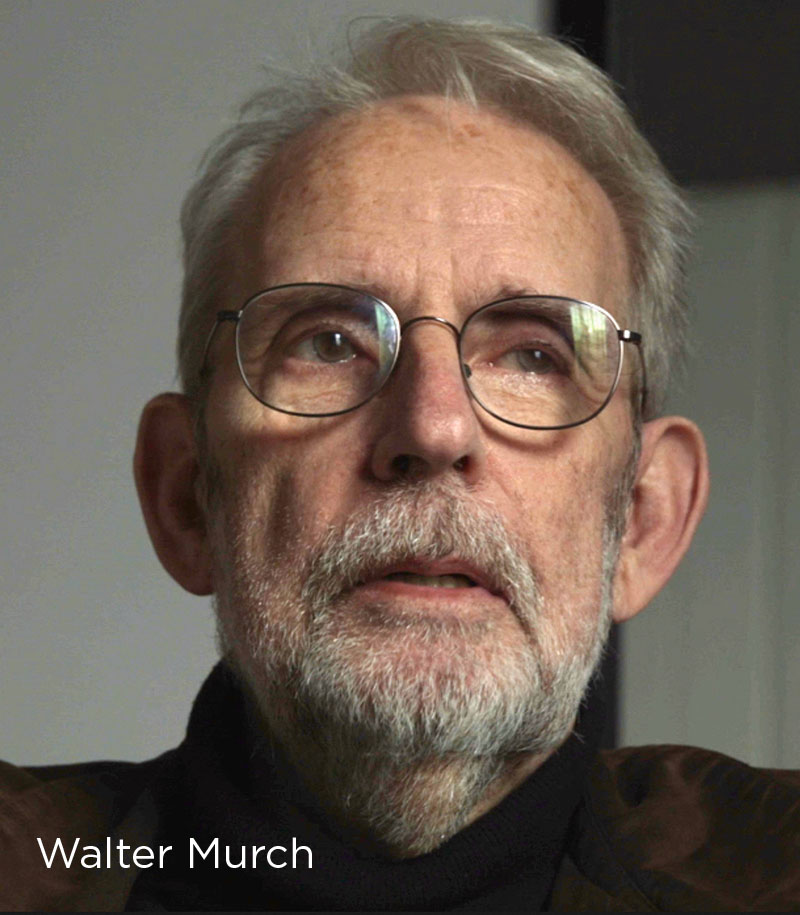

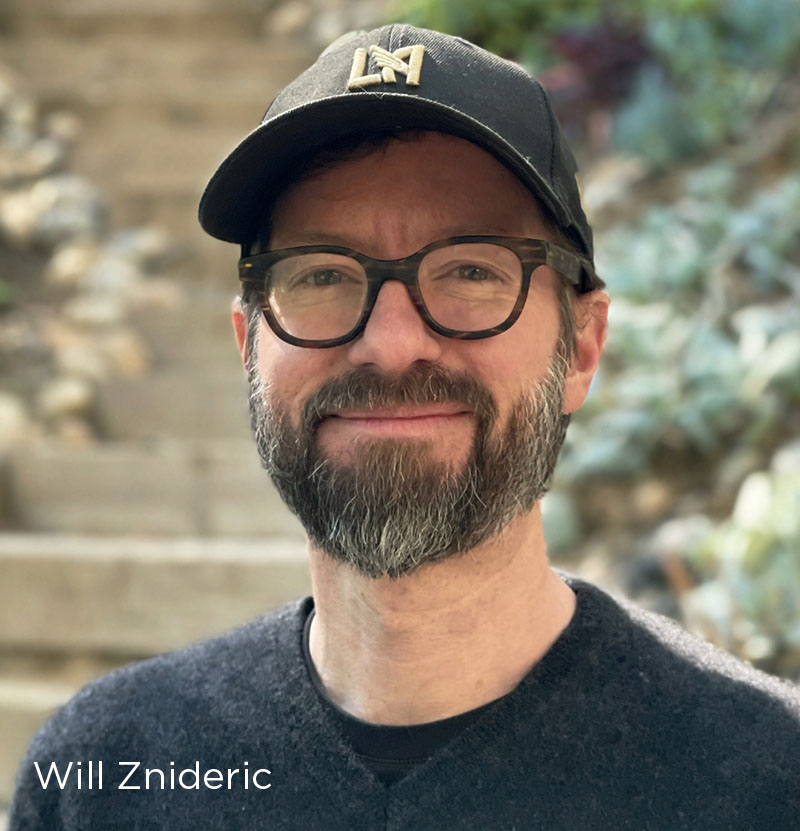

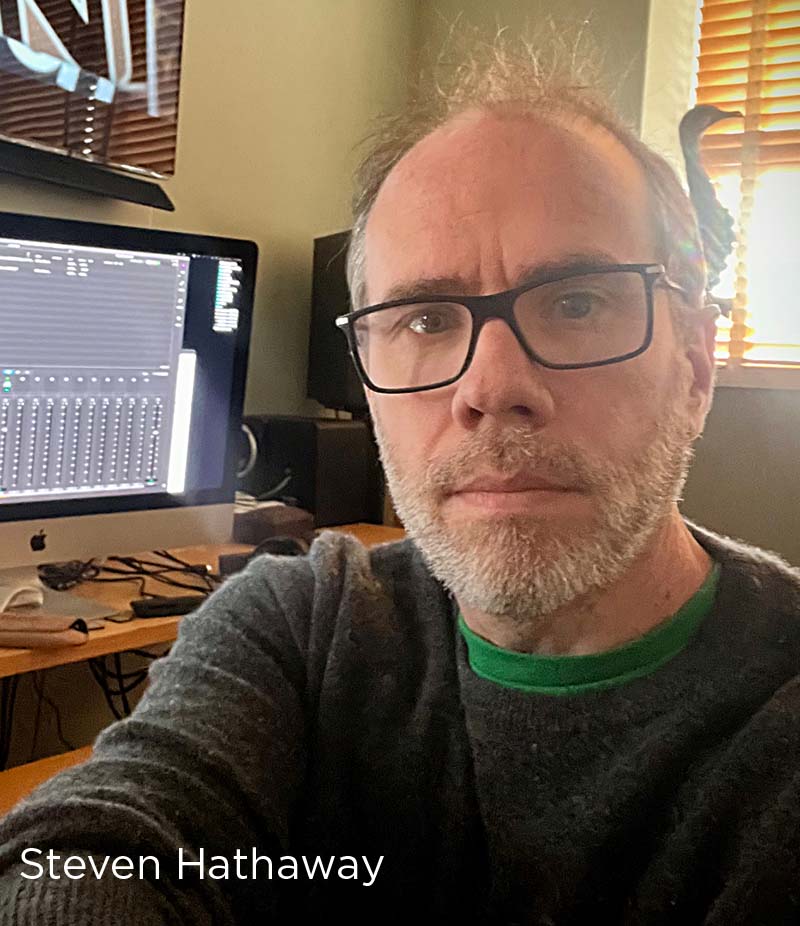

I surveyed a small, diverse cross-section of documentary film editors for their thoughts on the genre. These editors cover a range of experience working with award-winning directors. This editors’ roundtable includes Steven Hathaway (The Pigeon Tunnel, American Dharma), Neil Meiklejohn (Wild Wild Country, Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell), Walter Murch (Coup 53, Particle Fever), Kayla Sklar (Rams, Rise Again: Tulsa and the Red Summer), and Will Znidaric (Five Camera Back, Freedom on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom).

What is the difference between editing a documentary film or series and dramatic/fictional films?

Walter Murch: The real question: Is there a script before the start of production? If there is a script, it doesn’t matter if it is fiction or doc, the editor’s job is fairly clear: to interpret the script in cinematic terms given the material. If unscripted, then the editor’s job is different: to help build/discover the storyline and structure.

In unscripted, there is an abundance of events, but a paucity of interpretation. In scripted films it is the opposite: an abundance of interpretation, but a paucity of events. What do I mean by that?

In a scripted film, the editor may have 44 different readings of one line of dialogue. Four printed takes from eleven different camera angles and lenses. The decision becomes: which line reading and camera angle is best for this moment in the film. As for the events: there are only the events (the scenes) that are in the script. This choice is restricted relative to the profusion of interpretation of line readings.

In an unscripted film, the editor has only one line reading and one camera angle for each moment in the film. But, there will be many events (potential scenes) shot for the film, which may or may not be included in the final structure. It is the editor’s job to help decide which are the best scenes and in what order to put them, and then to make the best use of and framing for each single moment. Particle Fever and Coup 53 were both unscripted documentaries, and had, respectively, 400 and 530 hours of material to choose from.

You can compare scripted and unscripted to two types of science: Copernican and Darwinian. Copernicus had an idea (a sun-centered universe) and mined existing data to prove it. He did not make more than a few token astronomical observations himself. He had a pre-conceived idea to begin with and put that idea to the test. This is like having a script (a pre-conceived idea) and then putting it to the test of actually shooting it. Will the thing hang together? Will the weather co-operate? Will the actors deliver the goods? Etc. Etc.

Darwin on the other hand spent five years on an around-the-world voyage of discovery, making observations and collecting specimens, and then returned to home base and sifted through his “dailies” (so to speak) to find the underlying and animating story (evolution through natural selection). The idea emerged out of the evidence. This is like an unscripted documentary, where you shoot a lot of material and hope that a story will emerge from a careful selection of everything you have gathered.

Will Znidaric: When you start the process of editing a documentary, there is no pre-written script. It’s much more free form, and the job of a doc editor is one of discovery. The process is unique, a wholly different type of editing. Whether it is a cinéma vérité style of production, or one that leans on interview, or archive, or some combination of the above – you are going through all of it with an open mind. You are pulling material that not only helps to achieve the pre-stated concept or thesis, but also material that expands upon, and in some cases, even changes the thesis along the way. In that sense, the thing you are working to help create is almost alive. It breathes and evolves and grows and begins to even communicate with you on its own frequency more and more as you get closer and closer to it.

Kayla Sklar: Based on my experience (and this is definitely a generalization), a narrative editor shapes how the story is told, but a doc editor shapes what story is told. Most documentaries aren’t scripted, unless you’re working on something like a Ken Burns/PBS biography project. The director may have a thesis, but what story is the footage actually telling? It’s the doc editor’s job to help figure that out and to problem-solve when those don’t align.

Neil Meiklejohn: In documentary films and series, the editor is constantly writing and rewriting “the script” of the film. Most documentaries usually don’t have a clear story, so you are constantly trying to sort out what the best story is from the material you have. The words people say tend to be the driving force of that narrative. Careful arrangement of these sound bites gives you the strongest story. So, as an editor you’re essentially coming up with what the story is, along with the visuals being seen and sounds being heard to establish the tone of the film as a whole and throughout individual scenes.

Narrative is fun, because the script is written for you and most of the storytelling is sorted out in pre-production. You can really just focus on the tone of the piece sonically and visually. In documentaries, especially “talking head” docs, the writing is not done until post-production. Each day in the edit is different for an editor. Sometimes you are more creative with sound design or working on the visuals and some days are hard in terms of building out the film and “writing” new scenes. There are many moments where you think the story can take different directions and sometimes you have to try a few different options.

Many times on a documentary I suffer from “writer’s block,” where I need to jump into a new scene or rework an old one to push on. So, docs require a lot of “research and development.” In narrative, you may scrap a scene or two from the finished film, but for the most part you will see most of the script in the final film. In documentaries, you will spend weeks on scenes and multiple chunks of the film that will never see the light of day. Therefore, documentaries can take significantly more time, because of this trial-and-error period.

Even after the first rough assembly of, say, a true crime doc, you may realize that you need to work much more on the intrigue and mystery of an investigation, or clarification of things that are too vague. You are constantly adjusting how much and how little information (words or sound bites) the audience receives.

Different types of documentaries require different “writing tools.” For example, I have worked on a few documentaries that were very comedic. Even if your “talking head” subject is very funny, as an editor you spend a lot of time working on the timing and the wording of a gag or joke. In documentaries, it is significantly more difficult to edit something funny than in a narrative piece. In narrative, the writer, the script, and the actor have sorted it out for you before the camera even rolls.

On many bio-documentaries, peoples’ lives are not necessarily lived in a three act structure. Many times you have to sort out how to create a script of this person’s life or a moment in time that will be entertaining and understandable to an audience. It is no easy task. However. this is also what makes documentary editing fun. You really have an opportunity to tell a story how you as the editor see it and have the freedom to try lots of different things. The world is your oyster.

Steven Hathaway: The idea is the same: how to craft the best narrative out of the source material. For me a documentary starts with an interview. That interview is cut down to an essential state. You leave what is needed to tell the story. And maybe a few punctuating details. The same can be said for a scripted scene. You want to enter late and leave early. Build suspense and mystery, but also leave enough to follow the story. It is the basic editorial question: when is enough not too much?

In drama, there is more coverage, but less overall material. It is more about finding the right takes. In documentary, one is usually cutting a 90 minute movie from maybe 100 hours of footage. So it less about the best version and more about cutting it down while keeping the best moments.

Many documentary editors view what they do as a form of writing. Should they be credited as co-writers?

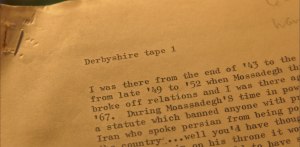

Walter Murch: If the doc is an unscripted one, then they should be credited as co-authors of the film. I think the editor should request that credit. This is what I did on Coup 53, and was granted that co-writing credit. I did not request that for Particle Fever, but perhaps I should have. I did proportionately the same amount of “writing” on Particle Fever as I did on Coup 53. In the end, no one received a writing credit for Particle Fever.

Will Znidaric: I used to believe very strongly that a doc editor should also be credited as a writer; but now I take a more nuanced perspective. The art of documentary editing is truly its own art form – very much like writing in so many ways. But, it’s also akin to sculpture, design, architecture, and even music composition. As anyone in the editing community knows – doc or narrative – what we do is considered an “invisible art,” which makes it challenging for people to appreciate its own unique subtleties.

Yet, if a young doc editor asks me for points of inspiration to better hone their craft, I point to the same types of material that any screenwriter would go to: “The Power Of Myth” series about Joseph Campbell, books about storytelling, books about screenwriting. Ultimately, the material you are sculpting as a doc editor is all in service of telling a compelling and engaging story.

Kayla Sklar: If no one else (director, story producer, etc) is getting credit for writing on a doc, then I don’t think it’s a necessary additional line. It’s within the scope of our duties. But I do think doc editing is definitely a form of writing. If someone can get a writing credit for punching up a script (as they should), then that’s similar to what a doc editor does to shape the director’s vision. A co-writing credit would be fair if there are other people on the doc getting a writing credit already.

Neil Meiklejohn: Most documentaries I have worked on have not had a writer, although a few have. Usually the writer credit is given to someone that is either writing the voice-over or sitting in with the editor and honing the story. I think each film or series should be taken on a case-by-case basis, as there are different ways of creating a documentary. But, I do believe if a writer credit is given to someone, filmmakers should also not ignore the contributions of the editor.

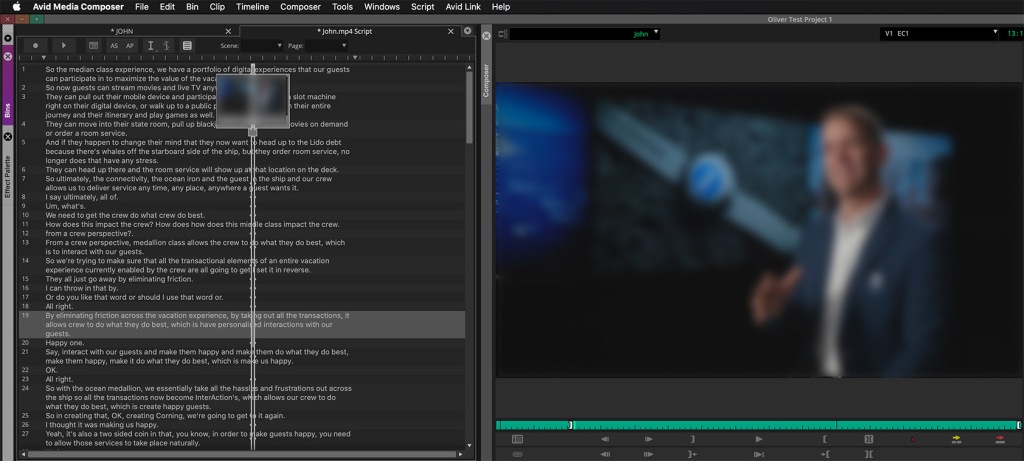

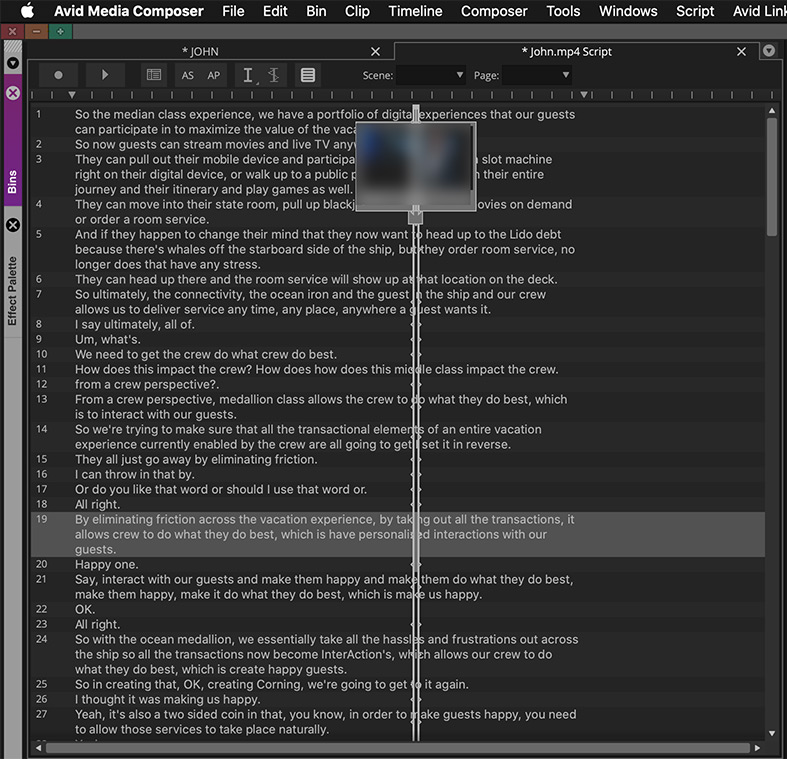

Steven Hathaway: I do not think of what I do in Avid as writing. I think it is closer to Tetris. If editors are writing the voice-over for a documentary and not getting credited, that is crazy. But I think story structure is part of the editor’s role whether it is scripted or documentary.

How have modern media platforms (Netflix, Apple TV+, Amazon Prime, YouTube, etc) impacted documentary films and series?

Walter Murch: As Chairman Mao said when asked about the impact of the French Revolution: “It is too soon to tell.”

Will Znidaric: On the whole, the growth of streaming services and platforms has fueled a complete boom time for the doc medium. It would not be hyperbole to say the last decade has been nothing short of transformative, as far as the doc medium is concerned.

There are many factors that come into play, including the accessibility and quality of production and post production equipment. But, also because there are now more entities that are hungry for doc projects. That means more documentaries get funding and find distribution than would have been imagined even 20 years ago. With that, naturally comes a wider spectrum of material that gets made – from more commercially viable, higher budget projects – to smaller, more idiosyncratic films/series. Ideally, there is room for an ecosystem that flourishes with a diversity of artistic voices. I am optimistic that can only grow in the future.

Neil Meiklejohn: For the most part, modern media has been wonderful for documentaries. Docs are no longer this boring genre of film. I think now we are seeing some of the most entertaining documentaries ever. People talk about docs around the water cooler. Documentary films and series are actually cool and popular, which is great, because there are so many great projects to work on as an editor.

On the other hand, I do think their popularity has also impacted streamers and studios, because now there is a sense of urgency to get the doc films out the door and into people’s homes. The schedules are now crazy fast. In the past, filmmakers would spend years making a documentary. These days films are supposed to be produced in months. These expedited schedules can hurt the creative and not allow you to make the best film possible.

Steven Hathaway: For me, it’s been very good. They enable me to be a part of telling more stories and reaching wider audiences.

Kayla Sklar: I think that there’s never been a better time to work in docs! So many doc series have entered the zeitgeist in the past ten years and especially since the early days of covid-19. Who would have thought that a series about a wild cat rescuer or cult leader would be weekly appointment television? And yes, maybe those aren’t as “serious” as the doc genre usually tries to be. But, I think it’s good for everyone when the mainstream public is open to the idea of non-fiction programming as a worthwhile way to spend an evening.

This roundtable discussion was originally published by postPerspective.

©2024 Oliver Peters