It’s easy to think of things in black and white, and to paint things with a broad brush of imperialism, colonialism, racism, militarism (take your pick). But dig just a tiny bit under the surface, and you’ll find that reality is rarely that simple. Is the solution really so obvious, simple to achieve, and definitively the right thing to do? Is it truly the case that the only obstacles to that solution are bad people, villains? Or are the obstacles at least partially logistical, practical, and due to the complexity of the situation? Are there really only two sides?

It’s easy to think of things in black and white, and to paint things with a broad brush of imperialism, colonialism, racism, militarism (take your pick). But dig just a tiny bit under the surface, and you’ll find that reality is rarely that simple. Is the solution really so obvious, simple to achieve, and definitively the right thing to do? Is it truly the case that the only obstacles to that solution are bad people, villains? Or are the obstacles at least partially logistical, practical, and due to the complexity of the situation? Are there really only two sides?

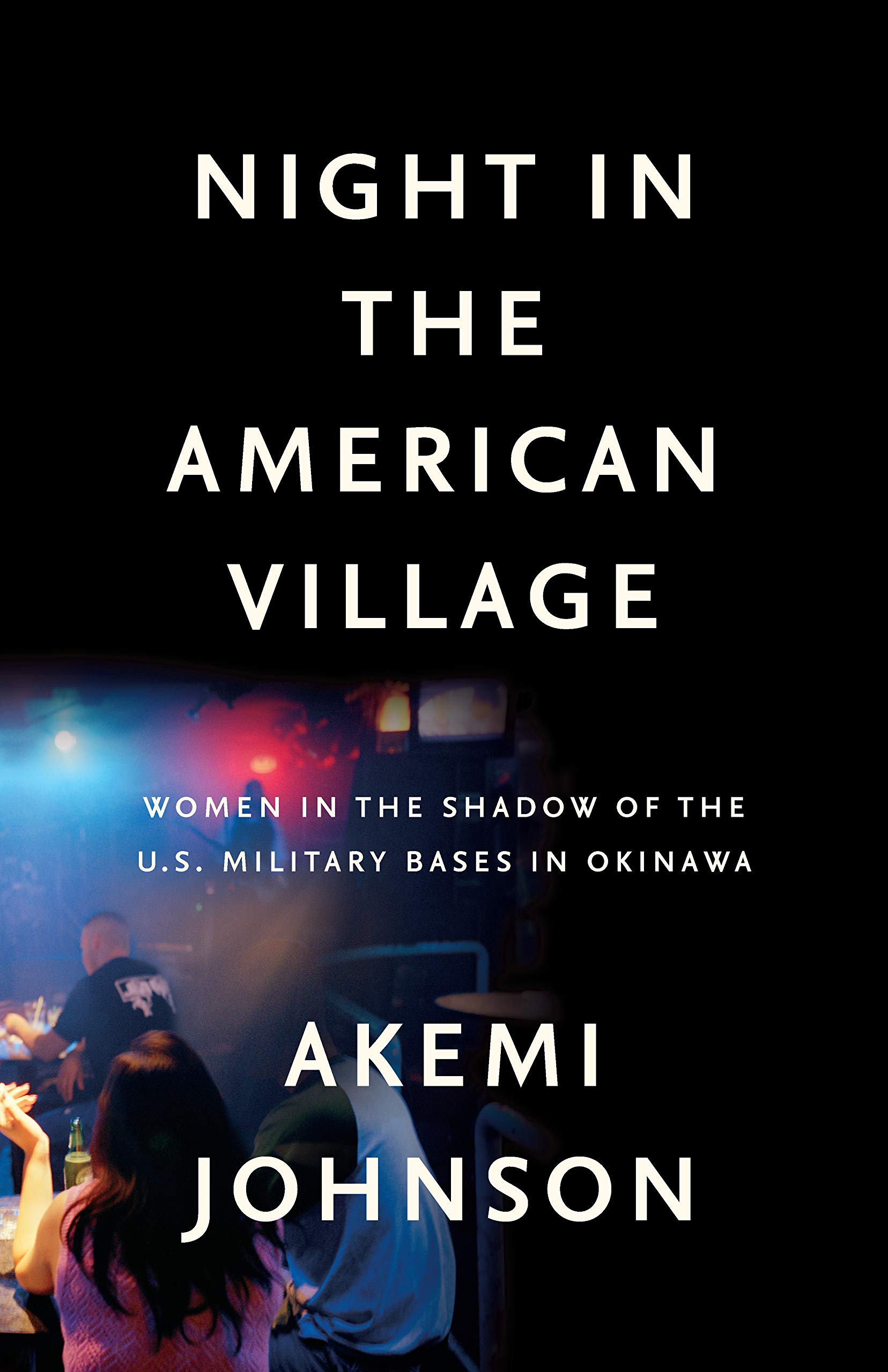

Sometimes it takes far more courage than it should have to, to simply be willing and able to say that things are more complicated than a simple full-throated defense of one side (and an equally full-throated condemnation of the other) would have you believe. And it is precisely that courageous stance that Akemi Johnson takes in her book Night in the American Village (The New Press, 2019). As she writes:

I was tired of hearing these crude dichotomies, wielded for political use. The pure, innocent victim and the slut who asked for it. The faultless activist and the rabid protestor. The demonic American soldier and his savior counterpart. They’re all caricatures, and if we’re using them to understand the larger political, sociohistorical situation – the U.S. military in Okinawa, and by extension the U.S.-Japan security alliance and America’s system of overseas basing – we’re not getting anywhere. Dichotomies like these disempower and silence the real people involved with the bases, the full cast of characters who often inhabit ambiguous spaces. (13-14)

I had the pleasure of meeting Akemi in 2017, while I was in Okinawa for my dissertation research, and she, I presume, finishing up work for this book. I waited eagerly for the book, and as soon as it came out, I dove right in; Johnson’s narrative style makes it, for sure, a page-turner, though due entirely to my own distractions and faults, my hopes and intentions of devoting myself to it and finishing it quickly did not pan out. Still, better late than never to draft and post a few thoughts, I figure.

A road construction sign along the highway in Nago. Photo my own, Dec 2016.

A road construction sign along the highway in Nago. Photo my own, Dec 2016.

Over the course of years of fieldwork, Johnson spoke with, and lived among, Okinawan women with a wide range of relationships with the US military bases, and she relates their stories in a way that brings to life the complex, nuanced, realities of life in Okinawa. Each chapter focuses on a different woman, in most cases given by a pseudonym, using their experience as a window into, or jumping-off point for, discussing a different aspect or different side of life in Okinawa. The women range from military wives, on-base workers, and young Okinawan “amejo” girls at clubs + bars disparaged for seeking relationships with American men to devoted anti-base protesters; from exotic dancers, English teachers, and foreign workers to multiracial students. Relating all of these stories through a focus on women brings, of course, a feminist perspective to the entire subject, and we do see discussion of issues of sexual assault, the intersections between military culture and toxic masculinity, interracial & international marriages, sex work, and other issues one might expect in a “feminist” or “gendered” approach. But centering women also serves to de-Other them, implicitly showing that by virtue of women being people (imagine that) all issues, by virtue of being issues that involve and affect people, are thus issues that involve and affect women. Johnson masterfully weaves these themes together in a way that makes the entire book read not like a Women’s Studies / Feminist book that happens to be about Okinawa, but rather an Okinawa book – a book about politics and society – that happens to relate its stories and arguments through a focus on some people (women) much more so than others (men), naturalizing and centering women’s experiences and concerns as human experiences and concerns.

The book is thoroughly researched and extensively footnoted (well, endnotes, but “footnoted” sounds better), but at the same time reads engagingly, at times narratively, less like much academic writing (including my own) and more like, well, exactly the sort of non-fiction “trade” book that it is. Sections of artfully phrased, compelling writing about the situation in a grand scope are interspersed with ones relating elements of the life of an individual woman living on Okinawa.

For foreign host communities, American bases provide jobs but also eat up land and spew American soldiers, American families, and American culture; they fill the air with jets, the roads with tanks, and the ground with toxic waste. The United States is the only country in the world to have this worldwide network of bases, and yet they remain largely outside the American consciousness. Americans unconnected to the military don’t often think of them. (6)

Arisa had grown up to marry one of the men behind the fence. She was in her early thirties now, a beautiful woman with bright eyes and freckles. Her husband Brian had retired from the military and worked as an on-base contractor, granting the family SOFA status and access to the base. That day, she was headed with their one-year-old son to an international festival, where Brian was performing with his dojo. The festival was off base on Gate 2 Street, but Arisa was using the base as a shortcut. Driving around it would have taken much longer. (91)

Night in the American Village provides us with the kind of personal, emotional, human sense of the situation that is so often missing from academic writing and thus so refreshing to find in literature and art. But Johnson does not skimp on hard-hitting, important, and interesting facts. I learned more about the US Occupation of Okinawa, and the facts and figures of the situation today, than I think I ever have elsewhere. Though the themes and information are scattered throughout the book, making it difficult to think of assigning students (or friends, or relatives) any one chapter, the volume as a whole is probably the best introduction to the complexities and realities of race, nation, economy, and the US base situation in Okinawa today that I have read.

A restaurant/bar directly across the street from the fences of Camp Foster Marine Corps base. Photo my own, Nov 2016.

A restaurant/bar directly across the street from the fences of Camp Foster Marine Corps base. Photo my own, Nov 2016.

One theme I found particularly compelling, which pops up here and there throughout the book but particularly in Chapter Eight (“Miyo”), is that of biracial or multiracial (or, as is commonly said in Japanese, “hafu“) identity, the place of multiracial people within Okinawa, and the character of Okinawa (not unlike Hawaiʻi) as a place where cultural & ethnic identities mix enough that Johnson (someone of mixed Japanese/white background) should write that she felt more comfortable in Okinawa than in mainland Japan. I found particularly compelling the way that Johnson illustrates the complexity here as well – tensions and issues of “race,” “ethnicity,” or “identity” are not so simply a matter of Black and White, American and Okinawan, Okinawan and Japanese, “half” and “full.” It’s also the multiracial folks who speak English and those who don’t; those who by virtue of their family members’ jobs have access to base (and the experience of that very different cultural space) and those who don’t; the influences of mainland/mainstream American and Japanese discourses upon multiracial kids’ ideas about what sort of appearances or features are beautiful, or normal, or desirable; American and Japanese notions of Blackness; and so on and so forth. The complexities of the pros and cons to special schools for mixed-race kids that provide a conducive environment among other kids with whom they share the experience of being mixed-race (and mixed culture, and so forth), shielding them from the bullying or harassment they might suffer in mainstream public schools, plus the opportunity to have American-style, partial American content, and/or English-language instruction, but then also the question of whether separating students out in this way makes it more difficult both for them and for their mainstream public school counterparts (who are mostly of “full” for lack of a better word Okinawan or Japanese ethnic background) to engage with one another and get along once the mixed-race students are forced into mainstream public high schools, and of course after they graduate and go out into society as adults.

Johnson’s line that “to me, Miyo [a young woman of mixed Okinawan/African-American background] belonged here, to this whole island” (180) stood out particularly strongly for me. I am not mixed-race myself, but after living in Hawaiʻi and Okinawa for some time, I think I have some sense of what she is talking about. She goes on to talk about how being of mixed-race on Okinawa isn’t entirely different from being Okinawan more generally, insofar as all Okinawans – those of mixed-race and those not – all struggle with being seen as Japanese enough, and with the various ways in which their “Japanese but not Japanese [enough]” status or identity manifests itself. While the conversation around mixed-race people so often centers on belonging to multiple communities, and/or feelings of insufficient belonging or insufficient “fitting in” with any of those communities, and while that is of course very much true for mixed-race people on Okinawa as well, I think it also rings very true that being mixed-race is so typical in Okinawa (as it is in Hawaiʻi) that it results in an identity that in some ways perhaps helps one feel like they belong fully to that place, perhaps even more fully than someone of solely Okinawan or, especially, Japanese background. When mixed-race, or (Japanese but not Japanese) Okinawan, people are the majority, then being mixed-race doesn’t make you stand out, different, an outcast, only partially or imperfectly belonging – your mixed identity is fully matching with the mixed identity of the society you live in. Indeed, while white privilege certainly rears its head in Okinawa as it does almost everywhere in the world, at the same time, Johnson writes that in Okinawa, many White kids feel it’s the half-Okinawan kids who are the cool ones, for their ability to feel comfortable and fit in both on- and off-base, and their ability to navigate both worlds. One hafu woman said that she used to wear brown contacts to hide her blue eyes, so she could look more Okinawan (182). There is a privilege to being Okinawan, as well; and we can see a similar phenomenon in Hawaiʻi, too, where the White (haole) majority may on average be more wealthy, more well-placed and influential in local politics and business, and “privileged” otherwise in many of the typical meanings of the word, but where they will at the same time always be outsiders amongst the Asian/Pacific Islander (most of whom are mixed-race) majority.

Barbed wire blocking access to Umungusuku, the historical site of the kingdom’s chief storehouse. Base fences block many Okinawans from accessing their ancestral graves, the former sites of their ancestral villages and the associated sacred spaces, and indeed land their family once owned or still does. Photo my own, Aug 9, 2013.

Barbed wire blocking access to Umungusuku, the historical site of the kingdom’s chief storehouse. Base fences block many Okinawans from accessing their ancestral graves, the former sites of their ancestral villages and the associated sacred spaces, and indeed land their family once owned or still does. Photo my own, Aug 9, 2013.

The imperialist and colonialist treatment of Okinawa, and the negative impacts of the ongoing US military presence there, are real, and the impacts are profound, serious, severe. From the wide-ranging assimilation efforts following the unilateral annexation of the islands by the Empire of Japan in 1879; to the willful neglect of Okinawa’s economic development in the decades following; to Tokyo allowing, or even encouraging, extensive death and destruction to be visited upon Okinawa and its people in 1945 in the hopes that in sacrificing Okinawa in this manner, mainland Japan, the “real” “Japan,” might be spared the same; to 27 years of US occupation; to nearly 50 years now since the end of the Occupation, years filled with plane crashes, sexual assaults, murders, environmental damage, noise pollution, and in 2020, the spread of Covid-19 by American servicemembers into an Okinawan civilian population that had had zero known positive test cases for weeks on end. And on top of all of this, the utter falsehoods which too many in the military believe, and teach to one another, about anti-base protesters being shills paid by the Chinese Communist Party; or that they’re allied with mainland Japanese right-wing ultra-nationalists; the kinds of lies that, through denying the validity and seriousness of the protest, makes it even more difficult to ever reach a solution. All of these problems are real, and profoundly seriously impactful, and I am now and expect I will always remain deeply sympathetic towards the Okinawan people in their fight for justice and equality, for cultural revival and pride, and for reconciling with an extremely difficult past and attempting to build a brighter future.

But that alone is not the end of the story. When I visited Okinawa for the first time, way back in 2008, I didn’t know what to expect in terms of anti-American sentiment. I had certainly experienced plenty of it at SOAS, which is a story for another time, and I had never yet been to Hawaiʻi; had no experience yet with navigating that somewhat similar situation. Anxious about being associated with any sort of stereotype of the bad American, whenever people asked me outright where I come from, or if I’m American, I answered that “I am American, but I’m opposed to the bases.” To my surprise, though, people very often responded with something along the lines of, “oh, it’s not that simple. You can’t just be ‘opposed to the bases.’ They cause a lot of problems, yes, but a lot of us work on base. We rely on the bases for jobs, and for the economy. You can’t just say ‘get rid of the bases.’ And, besides, after so many decades, we’re a little Americanized. It’s part of what Okinawa is today. So, it’s more complicated than that.” Now, granted, there are all kinds of factors – this was said to me most often by older men, so perhaps it’s not perfectly reflective of what most Okinawans, old and young, men and women, would all have to say.

Driving past the gates to, I’m guessing, Camp Schwab, near Henoko Bay. I’ve never been inside any of the bases on the island. Photo my own, Dec 2016.

Driving past the gates to, I’m guessing, Camp Schwab, near Henoko Bay. I’ve never been inside any of the bases on the island. Photo my own, Dec 2016.

It’s exactly that complexity, that nuance, that diversity of opinions, experiences, and perspectives, that Akemi Johnson so adeptly and engagingly brings to life in Night in the American Village – far more masterfully than I can in my summary of it. Johnson devotes multiple chapters to the perspectives of, and issues pertaining to, activists. The book begins and nearly ends (but for a few pages) with discussion of the horrific rape and murder of a young Okinawan woman by a former Marine in 2016, just months before I arrived in Okinawa for my dissertation research, and explores at length the dangers of the US bases, the damage and problems they continue to cause, and the uphill battle to convince Tokyo and Washington to finally give up on building a new, way-over-budget and devastatingly environmentally destructive base in Henoko Bay.

But then she also presents stories and perspectives of women who find working or socializing with Americans a way of escaping gender inequalities or patriarchal or sexist attitudes in “regular” Okinawan or Japanese society, or simply as a practical choice for a good-paying, stable job with flexible vacation time and so forth. American women who never really asked to be involved in any of this, but have simply been deployed – or have followed along with a spouse who was deployed – to somewhere new and different, where they don’t speak the language and where they’re just trying to get by best as they can; I’m not sure if Johnson provides the numbers, but I get the impression that a very considerable portion of the US servicemembers in Okinawa have never lived outside the US before. Many may not have ever left their home state before. She presents a complicated story in which there is, to be sure, much to the idea that the fundamental culture of the military “breeds violence both at work and at home,” that military culture breeds toxic masculinity and thus domestic and sexual violence, and that the military presence is just, overall, across the board, dangerous and damaging; but, then, at the same time, marking the bases as “pollution” means that everyone associated with them is also polluted, stigmatizing everyone who works on base or has relationships on base, which both prevents them from feeling welcome in the protest movement, hardening people’s attitudes and exacerbating social/political divisions, and creates further problems among friends, families, and so forth. I very much felt when I was living in Hawaiʻi, and I can easily imagine in Okinawa too, that local community can be very tight-knit, or interconnected. Everyone knows one another. Everyone, even if they are strongly anti-base in their political attitudes, knows people who work on base or who are married to someone who does.

We are introduced too to women like the artist Ishikawa Mao who are strongly proud of being Okinawan and opposed to the bases (one of her art books is entitled 「フェンスにFuck You!」or “Fences, Fuck You!”) but who found themselves in working and socializing with Black men, and Black Panthers in particular, forming a bond with these men over their shared racial/ethnic struggles (155). And women who fight for women’s rights and women’s issues (e.g. protesting against sexual violence) as their contribution to the anti-base fight, but who are then criticized for focusing “too narrowly on women’s issues,” something many activists wrongly see as “non-political,” or the wrong kind of fight (139). Women who have set up English-language conversation groups or other activities in an effort to build bridges: not ignoring or denying the problems of the bases but trying to address them and seek solutions in a different way. And women who are simply apolitical regarding the bases because, at least as some older activists see it, they just don’t know any better; they grew up around the bases as an everyday element of what was normal, were raised by general Japanese popular attitudes to think of activism or protest as radical, extremist, and were educated in a public school curriculum set on the national (Japanese) level, with little instruction on Okinawan history.

And in the process, with these women’s experiences and perspectives as the jumping-off point, we learn so much that I had never known before about the history of the bases and of protest in Japan; the history of the bar/club/entertainment districts (and the associated world of sex work) in Okinawa; issues and complexities related to what happens when base land is “returned” to Okinawan control (most often, it’s made into strip malls and the like); complexities of Japanese attitudes and laws surrounding race, gender, sex, and sexual violence; people’s conceptions and misconceptions about media bias, the true intentions (and identities) of protesters; and a variety of other topics.

While, as I’ve said above, I remain deeply sympathetic to the suffering and struggles of the Okinawan people, to the anti-base movement, anti-colonial discourses, and efforts to raise awareness of – and reduce instances of – sexual violence, at the same time we come to appreciate that nothing is black and white. There is both good and bad on-base, and off-base; good and bad within activism and protest; good and bad within sex work. Taking people as individuals, few fully match any stereotype; we are complex beings, multi-faceted. Perhaps we should not take everyone to be wholly guilty or innocent solely based on which side of the fence they stand on. I think that reading this at this time, given what’s going on in our world right now (and most especially back home in the United States, something which of course bleeds over onto the military bases, and out of them, as well as bleeding over into civilian life here in Tokyo and throughout the world in other ways), the lesson is perhaps all the more important. If we want to solve any problem in the world – if we want to heal divisions, bring people together, find compromises and solutions – we have to first understand the true complexities and nuances of the reality of the situation, and not the strawman version painted by rhetoric within one echo chamber or another. I think this goes for problems in our own country and communities, but I think that, despite not being particularly overtly a book about (anti-)Orientalism or indigenous perspectives or the like, Night in the American Village is also a powerful read for helping us to appreciate the profound importance of not going into another community’s situation, another culture’s problems, and thinking you already know the right side to be on, or the right way to understand the entirety of the situation. “I’m an American but I’m opposed to the bases” doesn’t cut it.

The “American Village” of the book’s title. A shopping center in Chatan, just outside Camp Lester and south of the massive Kadena Air Base, that doesn’t resemble a theme park nor any sort of reproduction of American townscapes like I might have expected, but is truly just a place to shop during the day, and get drunk at night. Even if it wasn’t way too far from Naha or University of the Ryukyus for my convenience, I still wouldn’t want to spend much time there; I generally try to avoid the military folks as much as possible. Photo my own, Dec 2016.

The “American Village” of the book’s title. A shopping center in Chatan, just outside Camp Lester and south of the massive Kadena Air Base, that doesn’t resemble a theme park nor any sort of reproduction of American townscapes like I might have expected, but is truly just a place to shop during the day, and get drunk at night. Even if it wasn’t way too far from Naha or University of the Ryukyus for my convenience, I still wouldn’t want to spend much time there; I generally try to avoid the military folks as much as possible. Photo my own, Dec 2016.

Night in the American Village is going immediately into any syllabus (reading list) for courses I might hopefully get to teach in future on Okinawan or Japanese Studies. Maybe even for World History, if I can squeeze it in. The one difficulty, though, is that if I were to assign Night in the American Village to students, it would be difficult to select which chapter to assign. Johnson weaves such a wonderfully intricate, complex, nuanced – and yet every easy-to-read, engaging, page-turning – picture of life in Okinawa today, it is difficult to pick out any one chapter to represent the whole. I may decide to have students all read different chapters, and then present on them so as to give one another an impression of the content, without having to burden non-native English speakers with reading an entire book.

I think it is so important for students – and, indeed, for all Americans (and Japanese) – to learn about Okinawa, to learn about this place that is so rich and vibrant and fascinating, and that also continues to struggle under burdens placed there by both Washington and Tokyo and yet which so few Americans (or Japanese) know almost anything about. I think it is so important for people to learn about the effects of imperialism and militarism, what it looks like on the ground, how it affects people’s lives, their culture, their peoplehood and sense of identity, and the path of their collective history. But beyond anything specific to Okinawa alone, I think it is also so important for people to understand and appreciate complexity and nuance, and this is something I think this book shows, teaches, in such a compelling and brilliant way.

I hope that many people interested in issues of militarism and its effects on civilian communities; colonialism and post-colonialism; women’s rights; history of protest; and so forth, far beyond those with a particular interest in or connection to Japan or Okinawa, will come to read this book. It sorely belongs on more undergrad + graduate reading lists, and on more “recommended reads” displays in local and big-box bookstores.

Futenma airbase, and a section of the city of Ginowan, the Okinawan, Japanese, American, and other civilians who live just outside its gates. Photo my own, Aug 5, 2013.

Futenma airbase, and a section of the city of Ginowan, the Okinawan, Japanese, American, and other civilians who live just outside its gates. Photo my own, Aug 5, 2013.

Read Full Post »