ArtSeen

Günther Uecker: Notations

New York City

Lévy GorvyNovember 7, 2019 – January 25, 2020

The title of German artist Günther Uecker’s fascinating show at Lévy Gorvy, Notations invokes many meanings of the term, from a system of symbols representing information, to the noting of and keeping track of ideas, to the staking out of intervals in time. The works on display here create a visible beat.

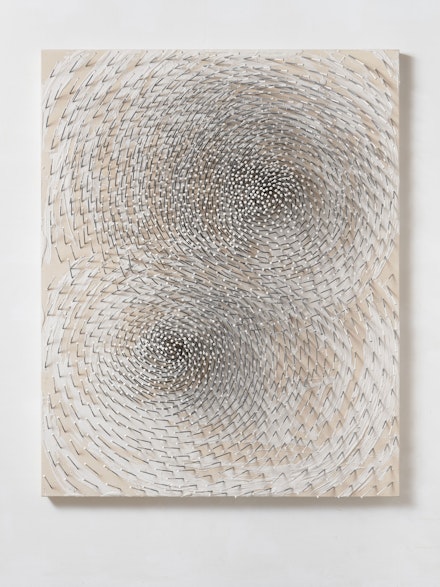

Uecker plays this cadence in seven new nail paintings, featuring long white-painted carpenter’s nails hammered into canvas-covered wood panels. In their accumulation, the nails form patterns like wind-blown trees or wheat stalks bending and flying, leaving shadows in their wake. Beneath the nails is an undercurrent of unexpected lyricism: Uecker’s paint handling creates surprisingly subtle and warm tonal shadings. The often excited motion suggested by these nail pictures—such as Weisser Schrei (White Scream) (2019), with its dense center, and Wind (2019), with its absorbing, angry darkness—combines Abstract Expressionist gesture with minimalist stasis and elegance, staging both against a basically neutral palette.

The nails are Uecker’s signature. He hammers into what surrounds him, appropriating everything from furniture to the natural world. In 1986, Uecker made a striking video with German filmmaker Hubert Neuerburg (Matricide in the Diamond Desert), in which he relentlessly plunges a spike into the sand while crawling naked across a desert, a large rock dragging behind him. He’s a wanderer and an excavator, punctuating his experience of time, place, and anything he finds along the way. Not least, there are the obvious sexual connotations, as he literally seizes territory, forcing the viewer to penetrate the surface with him.

Uecker also captures the feel and sensibility of sites across the globe in the language of light, color, and, motion. In Lévy Gorvy’s two-part show, he counters the nail constructions installed downstairs with the fluidity of watercolor in 15 works on paper. These sketches were executed from train windows, and most remarkably, each is quite different from the others in style—if not in coloring. The shades are warm, soft watercolor pastels, They aim to convey a fleeting sense of place, from Australia to Brazil, Egypt, Japan, and the United States, among many other locations.

Like his colleagues in the Dusseldorf artists group, known as ZERO, which included Otto Piene, Heinz Mack, and Yves Klein, Uecker uses largely unrefined materials—hardware, house paint, and glue—yet he allows for a distinct spontaneity and a surprising animation and assertiveness. ZERO rebelled against painting, yet I see Uecker’s work as painting by other means. As Uecker told Hans Ulrich Obrist in in 2011, “when Twombly exhibited his drawings in Wilhelm in 1960, which I think were done with feces on paper, it was unbelievably moving, spiritually; it was about the ability to give oneself visual expression that is not oriented towards history.” Uecker and the other ZERO artists were rebelling against the strictures of the war years and the artistic activities of the time, looking for new approaches to art that would enable them to essentially begin from scratch—hence the name ZERO. Uecker’s solution was to fix himself in the present, to seize the territory he traversed one watercolor image at a time, one hammered nail after another.

And yet, Uecker’s work—ritualistic and meditative, but nonetheless turbulent and unsettling—has an emotional and physical complexity that inevitably conjures both history and memory. The act of hammering nails into wood, for example, recalls barricading the windows of the family home during World War II. “This is what the nails represent in my work,” he told Obrist, “on the one hand a defense, like ruffled hair, like a hedgehog curling up into a ball, but on the other hand tenderness.” Even dreams of historical tabula rasa cannot fully escape the weight of the past.