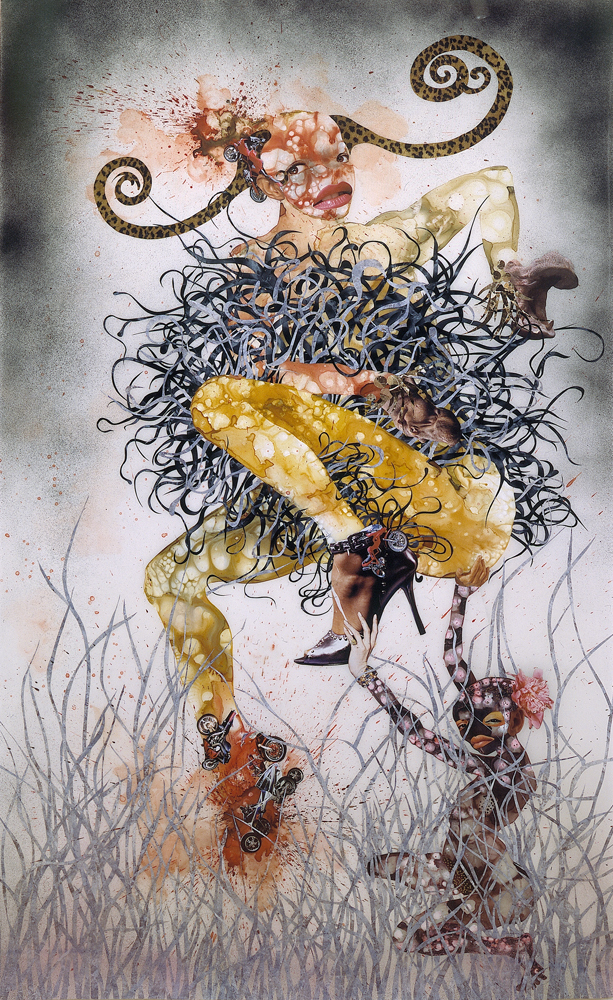

Riding Death in My Sleep, 2002, ink collage on paper, 60 x 44 inches. Collection of Peter Norton, New York.

Riding Death in My Sleep, 2002, ink collage on paper, 60 x 44 inches. Collection of Peter Norton, New York.

ORAL HISTORY PROJECT

An Oral History with Wangechi Mutu by Deborah Willis

by Deborah WillisFebruary 28, 2014

The Oral History Project is dedicated to collecting, developing, and preserving the stories of distinguished visual artists of the African Diaspora. The Oral History Project has organized interviews including: Wangechi Mutu by Deborah Willis, Kara Walker & Larry Walker, Edward Clark by Jack Whitten, Adger Cowans by Carrie Mae Weems, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe by Kalia Brooks, Melvin Edwards by Michael Brenson, Terry Adkins by Calvin Reid, Stanley Whitney by Alteronce Gumby, Gerald Jackson by Stanley Whitney, Eldzier Cortor by Terry Carbone, Peter Bradley by Steve Cannon, Quincy Troupe & Cannon Hersey, James Little by LeRonn P. Brooks, William T. Williams by Mona Hadler, Maren Hassinger by Lowery Stokes Sims, Linda Goode Bryant by Rujeko Hockley, Janet Olivia Henry & Sana Musasama, Willie Cole by Nancy Princenthal, Dindga McCannon by Phillip Glahn, and Odili Donald Odita by Ugochukwu C. Smooth Nzewi. Donate now to support our future oral histories.

9/24, Bed Stuy, Brooklyn at Mutu’s studio.

Wangechi Mutu was born in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1972. She received a BFA at the Cooper Union and later received an MFA from Yale University in 2000. Her work has been featured in solo exhibitions at institutions including the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin; the Wiels Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels; the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. She has participated in group exhibitions at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Bronx Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and numerous others—including the Tate Liverpool, the Vancouver Art Gallery, and the Palais de Tokyo. Mutu’s work explores the interplay between “the real” and fiction, combining ideas found in literature, history, and fables to examine female identity and women’s roles throughout history. She has made sketches and created collages and video about the female body since her days at Cooper Union. In my view, allegory is central to her work and is made apparent through the use of collage, and fragmented or constructed imagery. The complexity of her layering of objects, mark-making, and collage is achieved through her use of translucent materials, photography, and drawing. She also works with performance, a central component of her video installations. For some 15 years now, I have had the distinct pleasure of seeing Mutu pose for the camera for other artists. As I’ve followed Mutu over the years, I have had opportunities to see her work in museums here in New York City, in Toronto, and in galleries in cites both large and small. I love watching people engage and question as they view her work. My own writing and artwork also focuses on the black female body, and I am intrigued by the way Mutu manages to successfully focus her vision on sexuality, desire, and colonialism—while also incorporating girl culture, as well as popular and art historical references. She keeps her viewers engaged as she delves into and visually illuminates universal stories about ritual and myth. In this oral history, I hope to introduce new readings of how her work is viewed, consumed, collected, appreciated, and critiqued.

Deborah Willis Tuesday, September 24, and we are here in Brooklyn at Wangechi Mutu’s studio in Bedford Stuyvestant. Wangechi Mutu has been a special person in my life since 1994, and I really appreciate the opportunity to work with and learn more about Wangechi.

So, the first question: Where were you born?

Wangechi Mutu I have to say that I’ve been a massive admirer of your work, so this is a little nerve-wracking and wonderful. It’s everything that I dreamed would happen eventually, that we’d have this conversation. I was born in Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, in Nairobi Hospital, the second born in a family of four, and I was raised in Kenya. I went to nursery, primary, and secondary school in Nairobi at Loreto Convent Msongari, and then I left when I was 17 to go to the United World College of the Atlantic in Wales. But I feel like my brain, my consciousness, was built and formed in Kenya, and I’m Kenyan in heart.

DW Your parents, what are their names?

WM My mother’s name is Tabitha Wambura Mutu and she is married to my father, Gethoi Gichuru Mutu. They are both from this highland area in Kenya where our people are from, Nyeri. My grandparents are also from that area, and so we are Kikuyu, essentially. The Kikuyu are one of the original, precolonial nations of Kenya. The Kikuyu live in various parts of the country today, but before Christianity was introduced to central Kenya, we lived mostly on the slopes around Mount Kenya or Kirinyaga (Place of Brightness) where we farmed the hilly slopes. My parents got married in 1969, had my sister in ‘70, and had me in ‘72, and had my two brothers after that.

DW The Kikuyu are special to the Willis family too because Songha Thomas Willis, my nephew’s father, was a Kikuyu. And I recall when Songha met you in the mid-‘90s and how exciting it was to have that connection with you.

WM I remember that.

DW So, as a second-born, what’s the distance in terms of age among your siblings?

WM My brother after me is four years younger, and my other brother is eight years younger. My sister is two years older than I, so we’re much closer in age. And, yeah, three of us are here; my two brothers are in the States. Irungu, my youngest brother, is an actor. He lives here in Brooklyn actually, and Kamweti is in Washington, DC with his two children and wife. I’m not sure what he does, to be quite honest! So there’s a little family of us here, but everyone else is back home in Nairobi.

DW So, why Wales to study after living in Kenya?

WM In fact, I had no interest in going to Wales, until I realized that the best of the schools I interviewed for was in Wales. But I was not interested in going because the United World College actually has another school in Swaziland, and several others all over the world, in Singapore, Italy, America, and Canada. What happened was that I was one of these kids who did really well in academics, but I did a lot of other things. And when I was fifteen, I was in a play and had the lead role in a girls-only school; the lead role was a guy. I was this male character. A mentor of mine, Richard Leakey, came to see the show. He didn’t really have an interest in theater or the arts as such, but somehow, when he saw me, it occurred to him to suggest that I apply to this school in Wales. I have no idea what, exactly, he saw in me. In fact, I’ve never asked him why he suggested it. I remember him telling me, “I don’t leave the house in the evening”—they lived kind of far from Nairobi—“but I’m coming to see you in this play.” And then, literally in the next couple of weeks after that, he suggested this school for me.

DW What is the name of the school?

WM It’s one of the United World Colleges. They’re international schools. Their philosophy is to educate kids from all over the world together at a specific time in their lives because that promotes multicultural understanding, diplomacy, and intercultural development. It’s the kind of thing that’s happening a lot more in many schools now. They were way ahead of the curve then, and at the time I couldn’t have dreamt of anything better than to be in an international school environment. So I applied to the school thinking, “I may go to Swaziland.” And then, when I got in, my mentor said, “Why don’t you go to the best—the original school, the one in Wales?” And I was like, “Why would I want to go that far away from my family?” But, ironically, I did want to get away from home—like many teenagers do at that age in life. I didn’t feel like I fit in my family; I didn’t feel like I was getting along with my dad. I felt at odds with many things. Now I realize that that feeling at odds with things was probably the feeling that I was an artist. I was inquisitive in a particular way and creative, and I didn’t see things quite the way everyone else did. But I remember feeling, specifically at home—I didn’t feel like I fit. So I was very excited about the opportunity to leave, but I still had to get used to the idea that I would be leaving my family to go abroad to school. And that’s when this journey away from home started, because I never went back to live in my parents’ house.

DW What was your house like?

WM Growing up?

DW Is it two stories, one floor?

WM I love that question because our house is no longer there, but we actually live on the same plot where I grew up. It felt like it was on the outskirts of Nairobi at that time. Now it’s not, because Nairobi has grown so much it’s been subsumed, and it’s actually more central. But we lived in a bungalow, a one-floor layout, with maybe four bedrooms and two bathrooms. I think it was three, originally, and my parents extended it. We had a lot of space around to play. It was a very suburban life too, in the sense that everyone had their house, with a little compound and a gate, a very African metropolitan kind of existence, in the sense that you have safety issues. If you have a middle class lifestyle, it means that you probably have more money than many other people around you, and, therefore, one puts up security around your house.

DW What did your parents do? What kind of work?

WM My dad was a teacher for secondary school and later, for university students. He did radio work at some point, as a radio DJ, you know, on his own radio show. He worked as a civil servant. He didn’t enjoy it though, and I think there were political aspirations that he realized he wasn’t going to accomplish. He eventually went into business, and, soon after, in the mid-‘80s, the economy shifted, and his business didn’t do very well. So he started reading a lot, studying, and looking at his life and examining what he wanted to do. He had a midlife crisis like no other. (laughter) And he started writing a lot of poetry and making us read it. I remember that very clearly. And he started this obsession with indigenous trees. It gave us this love-hate feeling about what that meant, indigenous trees. He would preach to us about learning their names, what they do, how they grow. He’d pull over the car, get us out, and make us look at a little shrub, and go, “This tree…da-da-da…” Now that I’m the same age as my father when he was going through this—40, 41—I realize that it was part of his self-discovery. He now is a researcher, more of an academic in Kenyan history. He went through that whole entire journey, ending up in something that I think suits him very much; he researches, he writes. He writes biographies, ghostwrites biographies for people, and he still lectures a lot. My dad still talks about the things he’s learning quite a bit, which, growing up, was the bane of my existence. I hated my dad’s lectures. I used to make this joke, “I wish he would just smack us around a bit more, because I really don’t want to hear this!” (laughter) But my dad is very knowledgeable, very interesting, and that’s what he does with his life now. My mom was trained as a nurse-midwife; a very nurturing person, very, very caring, very maternal mother. She is still a healer in that way. She still is able to nurture, care for, and heal the individuals around her.

DW That’s beautiful. Does she deliver?

WM No. My mother delivered for only a couple of years. Then she changed her nursing schedule because of the kids, because of us. She said it was so hard for the girls, for my sister and me, when she had to go for night duty, and eventually she knew that that’s not what she wanted to do. Interestingly enough, though—I always ask her questions, bizarre questions about nursing—and I didn’t know this, but she’s also very queasy about surgeries and wounds. As am I. So she wasn’t as fond of that part of the work. She of course had to work in surgical theaters, for all that invasive kind of work that they have to do as nurses. And she said she didn’t enjoy it at all, that she had a hard time watching operations. It came up because we were talking about people who kill or slaughter animals, and she was like, “Oh no, I can’t handle that!” And I was like, “But, Mom, you were a nurse.” And she said, “That is the worst part of the job.”

DW But what’s funny, listening to this story, is that it connects to your artwork today—from storytelling, to the trees that you grew up with, to the aspects of dissection that your mom told you about. It’s fascinating. Your work is nonlinear in film, on paper, and on canvas, but a strong narrative is often “read” throughout the work, whether with the use of original photography, glossy magazine papers, erotic postcards, fabric, audio, installation

WM Oh my goodness. Oh yeah. And I’m also coming to terms with how much all of these things have influenced my choices and my interests. Also, my interest in things that I can’t stomach, stems from being surrounded by these types of things. My mom had a lot of medical books on tropical diseases.

Pretty Double-Headed, 2010, Mixed media, ink, collage, spray paint on Mylar, 34 × 41.75 inches. Private collection, Los Angeles.

DW Yeah, there is a lot of texture in your works, particularly on the figuration of your subjects.

WM There is nothing more insanely visually interesting and repulsive than a body infected with tropical disease; these are diseases that grow and fester and become larger than the being that they have infected, almost. It’s different from temperate diseases, which seem to happen inside of the body. Tropical diseases—elephantiasis, polio, and worms that grow in people—create new worlds and universes on your body. That’s what has always fascinated me. And of course, when you have these books on tropical diseases, you don’t find the most moderate example. They give the most extreme patient, that’s who’s in there, with the goiter hanging down to their knees; it’s craziness. But I used to look at these things, and as much as I was disgusted by them, I was like, “Oh, oh, turn the page, next one, all of them!”

DW Trapped in your memory. But what about school, when you went to Wales? Did you live in the dorm?

WM Yeah, it was a very progressive kind of school.

DW In terms of international students, were they from Africa and…?

WM From all over Africa. That was it. It wasn’t an expatriate school, or for ambassadors’ and diplomats’ kids. There was a very big diversity, even kids who were…

DW And from Wales?

WM The rule in Britain is, I think, that 25 percent of the student body has to be British, if it’s in the UK. So they would actually try to keep that number.

DW Black British kids as well?

WM There weren’t that many black British but there were poor white kids, and of course wealthy ones. There were Indian Brit kids, but I don’t remember black British children. It was funny; the US kids were like that too. The US would send mostly white kids, and it would be like, “Where are all the other ethnicities?” But what I liked about at least the African kids was that we were from everywhere. And that doesn’t happen often. So there were tons of Southern African kids, Zimbabwean, South African, Botswanian, Namibian. There were a couple of Egyptian kids, us, the Kenyans, Nigerians, Ghanaians. There were gender things, certain countries sent more boys than not. But there was a Libyan kid. I say that because this was around the time when Gaddafi bombed the Pan Am plane, and Mandela was being released, and apartheid was finally being broken down, and so all of these events created discussions among the young people that were so important for my development, and for my memories. We were that age when you didn’t avoid the issues. There was no reason to. A political incident would happen, and we would have a debate. We would stand there and talk—you’re young, and you don’t know not to say things, so you say what you have to say, you hear things, you discuss things. And you get to the core of the issue faster than adults do. Not that we could do anything about it, but we actually were able to break down the reasoning, “Oh, this war is about oil. This is not about this religion or that history. But the fight is for oil.” It was profound; it was amazing. It took me years to shake off those two years.

DW And to have that broad range of discussion, where you could imagine. I grew up in Philadelphia and remember a lot of poets in the Philadelphia area. I used to just listen to people, how they created ideas, and I was younger, but I was always interested in that arena. But one of my dreams also was to become an artist.

WM Oh, I didn’t know that.

DW And apply to Cooper Union, which was impossible to get into, as most people who I know have experienced.

WM It’s hard to get into!

DW So with Wales, did you study art?

WM That was actually the turning point for me, in terms of art. I knew that I had this ability, this gift for art, but it hadn’t been fleshed out or developed in Kenya because we had a very rigorous, academic, monotonous class/lesson setup. We did still lifes for years. And when I say for years, I remember four years of sitting in front of a pot, a gourd, a cup, “Draw this!” And I remember thinking, “Why would anyone want to be an artist? This is the most boring thing.”

DW So it was part of the curriculum?

WM It was part of the curriculum. My teacher just thought that the most important thing was to learn rendering and technique, and there was no conceptual or experimental aspect to it. Maybe it’s not even his fault, maybe it’s just the way that he was taught.

DW Yeah, he was trained in that way. But there was that mixture of art and performance, the aspect that your mentor saw you comfortable with—the world stage.

WM I think that’s what it was.

DW I was thinking, imagining looking at you as a young woman, and then seeing that you could be broader than that time, that you could actually survive in a place like Wales.

WM But you know, interestingly enough, the school didn’t want geniuses, per se. Or if you were this physics nerd, doing adult theories or things beyond your age, you weren’t necessarily the right person for this school. First of all, everyone had to leave home, so socially it was very much about: Can you adapt? Can you get through the homesickness? Can you be around other kids and use your understanding of family and readjust it to this new group? They wanted this versatile kid who would contribute because they had so many other abilities and activities. They wanted someone to do journalism, and environmental science, and all these things. So maybe that is what my mentor saw, and it was clearer to him then than I even understood—but as I said, I haven’t asked him since.

DW Did you do sports?

WM Yes, I did a lot of sports. I mean, at Catholic school we had everything that you’re supposed to have at a private school. We had field hockey, swimming, tennis. We had long distance running, track. We didn’t have basketball, we had this other, British, female-ish—I say that because there’s no other way to say it. Boys don’t play netball. It’s called netball, and it’s a colonial, British, basketball derivative. No one but other ex-British colonies seems to know what the hell netball is.

DW But the goal was to put the ball in the net?

WM In the net, yeah. But you don’t dribble. The ball can only touch the ground once. It’s a lot more throwing, and even when you’re shooting, you have to have your feet on the ground, which is interesting. With basketball, there’s a lot more flying. Netball, you have to aim; it’s strange. We loved it because it’s a fast game, the way basketball is, and it’s an athletic—it’s a cool game, but I can’t really play basketball, as a result.

The bride who married a camel's head, 2009, Mixed media collage on Mylar, 42 × 30 inches. Deutsche Bank Collection, Frankfurt, Germany.

DW What about dancing? Did you dance?

WM We did a lot of East African dances. I love that we did it; we did it for Mass.

DW For Mass?

WM For chapel. (laughter) I know.

DW So talk about that. You grew up Catholic?

WM I grew up Catholic in school. My family is Protestant. My school was a Catholic convent, girls-only school. Catholic Mass into the late 20th century seems to be way more adaptable to inflections of various cultures. Like now I understand why Haitians use Catholicism and mold it around their culture: The Africanisms are inside Catholicism, Candomblé and all of these…But I realized that that was what was happening at our school in spite of how rigid the Catholic Irish nuns were. They seemed very happy to have African music, Kenyan songs, Kenyan dances, in the chapel. They encouraged us to do these things. So while we were bringing the host up to the altar, we were also encouraged to create these incredible dances.

DW Fantastic.

WM It was amazing.

DW Did the nuns dance also?

WM Oh, no. No. (laughter)

DW It would have been fascinating if you had gotten them to.

WM I’m sure they enjoyed watching us, because it was beautiful. Actually, when I was fifteen, my class took a trip to France and Switzerland. Forty girls. It was incredible! To sing in various convents in Europe and travel around, singing as a choir, but also visiting all of these old, gorgeous cathedrals that were quite empty, because Christianity is in a different place in Europe than it is in Africa. So then we amped up, we brought even more songs. There’s a lot of beautiful African liturgical music because, of course, Christianity has translated everything into various native languages in Africa.

DW Also the aspect of pageantry and color.

WM Oh, yes. Absolutely. Actually, it was one of the most fun things about being in school.

DW You rarely hear any fun things about Catholic school.

WM I know!

DW I always heard that Catholic schoolgirls would hike up their skirts after school because...

WM Oh, roll them, that is what we did.

DW Yes, because they were below the knee, and waiting for the bus home they rolled them up.

WM Yes, trying to be a little bit more funky than they were obviously allowed to be. Then, there was no nail polish, no hair braiding. Tons of rules. But they did allow for creativity in Mass. We used traditional percussion instruments, drums, maracas, all these things that were Kenyan-derived. And it was a blast. We had a great time. And we also had the more Western kind of instruments. I played the flute, for example. We had violin, flute players, saxophone, all of them. And so we took those instruments to do the more traditional songs. My family is Presbyterian, however, and I would literally fall asleep at our church. It just wasn’t as interesting, and there wasn’t the same kind of creative investment. No asking, “We are here, now, in Kenya, so how do we make this suit who we are as a people?” Protestants are notoriously puritanical. They’re practical, sometimes to a fault. They’re allergic to embellishment, flourishes, emoting, and ostentation. So these values were forcefully “adopted” in the new African Presbyterian communities. The first Scottish Presbyterian mission is a few miles from where my grandmother lives. So being sent to a girls’ Catholic school was an extension of this religiosity and Westernized living.

Exhuming Gluttony (Another Requiem), 2006-2011, Mixed media installation, animal pelts, wood, bottles, wine, packing tape, and blankets, dimensions variable. Daskalapoulus Collection, Athens, Greece. ©FMGB Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa, 2011. Image courtesy of the Artist. Photo by Erika Barahona-Ede.

DW So after Wales you decided to apply for art school in New York?

WM Yes. The international school I went to opened up this box in me. It really addressed the fact that I was born an artist, and art was what I wanted to do. “Art is not just this little thing that I’ve been doing all these years, it’s actually a universe, a world of opportunity and I can approach it however I want.” And that’s when I decided to apply to art school, because that’s when I realized, not only do I feel like I have an ability in this field, but I knew that I could do it for a long time. So if it didn’t work out, I knew that I could just keep pushing it—because it wasn’t the sort of thing where I felt, if I didn’t like it, if I didn’t make enough money, I couldn’t stick with it.

DW It wasn’t a back-up plan.

WM No. It didn’t feel like it.

DW It comes from your heart.

WM My dad was also going through such a hard time because of his own professional, personal decisions, and I remember thinking, I don’t want to be his age and be saying, “Oh, I wish I had tried that thing and maybe I should start now.” It means relearning, or unlearning, or starting again. I didn’t want to be at that point where I was regretting. And I understand, he came from a very different generation. He wasn’t able to pursue his art. It would have been intolerable, insane, and impractical. So I was hedging: Okay, let me see, I’m going to have time; I’m 18, I can take risks. I can push this thing and see how far it can go. And so I applied to school in the States, because I couldn’t really apply to a university in Kenya, the UK, or Europe—the schools were way too expensive. The States allowed me the chance to get some financial aid. There are more international applications coming to art schools here; they had an office in Nairobi for American universities, so you could go talk to someone. And I decided on four schools: Pratt University, Cal Arts, Philadelphia School of Art, and Parsons. I got into three of them and chose Parsons because it was in New York. And because it seemed the most appropriate (on paper). When I got to Parsons, of course, I realized it was more of a design school, and that was a little bit disappointing because it’s a very good design school, but I didn’t feel like I was getting what I wanted academically or from the fine art side of it.

Foxy Lady, 2008, Mixed media installation, 93 × 104 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

I had applied to other art schools when I was doing a stint on this very remote island in Kenya. I was working as a muralist and museum painter. Several other young artists and I were hired to help work on this very odd idea to try and turn this fort into an environmental museum. I was 18, living on my own in a remote part of the island with five dogs and the farm handlers. It was such a magical, remarkable time in my life. And it gave me time to think and to draw, and to put together a home test that I felt proved that I belonged in an art school. And I got in and didn’t have the money; in fact my father, my family didn’t have the money either. So I went to my mentor, this man who had decided that I should go to international school. I said, “You know what? I’ve gotten this far, and now I’ve gotten into the Parsons School of Design, and I don’t have the money. I need this much. Can you help me? You just need to help me for one year.” Foolishly thinking, once I got here, I would figure it out, I could make $30,000 a year, while I was going to school full time. I had no idea what I was going to do, but I thought that I could improvise or approach the issue once I was in New York City. Of course I got here and the tuition proved to be too much. That was the other reason why I couldn’t stay at Parsons. So I left. I had the option to go back home, which was, from the perspective of a young immigrant, a failure. Something is really wrong when you have to go back home and you haven’t quite made something of yourself over there. But I wanted to stay and complete my degree. And that’s when I discovered—believe it or not, I didn’t even know about Cooper—I discovered Cooper Union in that time that I was looking for another school. It just blew my mind that there was this tuition-free school around the corner from Parsons. Like six, seven blocks away from my previous school. When you don’t have any other choices, you just funnel everything into it—I mean, I worked on drawing their home test like my life depended on it!

DW There’s the importance of that still life drawing class that you had. (laughter)

WM Exactly. And I thought about my teacher in Kenya—Oh God, it comes back to drawing. It all comes back to drawing. So yeah…and I thought that was amazing too, because it leveled everything out. Drawing is the basis. So, I got into Cooper, and I got in as a transfer student, meaning I didn’t have to start from the first year, and that was even harder. Actually Cooper, the way they work is, if people leave, or if somehow there’s a dropout, then they make a couple of spots available for transfer students. That made my accomplishment real. I knew: I’m supposed to be doing this thing, because there’s this door that has opened up for me that I could never have imagined. Also, you can’t apply to Cooper from outside of the US.

DW So you had to be here?

WM You had to be here. You had to be a resident. As an immigrant, after one year of living in a city, you’re basically a resident of that city. Then other things have to fall into place, but that allows you to do certain things like apply for permanent residency. So it was bizarre.

DW Did you meet a lot of artists, your first year here in New York? Or, how did you create a community, or an extended family?

WM That is actually an amazingly perfect question, because at that point, moving to Cooper opened up the art world for me. At Parsons, I was in New York City, I went to galleries and museums, but I met amazing people through Cooper Union. Fred Wilson, Hans Haacke were there. As a result of Fred Wilson, I met people like Thelma Golden and Glenn Ligon early on, because that was the time of The Whitney’s watershed 1993 Biennial and Black Male show in 1994. [Black Male: Representations of Masculinity in Contemporary American Art].

DW A really significant period.

WM Oh my goodness. I thought this was how it was all the time, by the way, because I’d just kind of dropped into this moment.

DW And Thelma had such a time with the Black Male show.

WM Absolutely. Even the Biennial that Thelma co-curated, there was all of this incredible critical energy that was alive, and political, and conscious.

DW And that’s what made it happen, I think, that the energy, that the concept of black males, and the Biennial, and then you as a student, coming into this flowering of emotions. The mid-‘'90s was an important moment in the arts. There were a lot of artists holding MFAs and BFAs and showing works all over the city and the country. In my view, the mid-90s were an exciting time for the arts and witnessing new works at the Whitney, the Studio Museum in Harlem and the New Museum—just to point out the larger institutions—but the galleries were also opening up and hosting powerful shows.

WM Absolutely. I couldn’t have asked for a more amazing moment to enter art school and the discourse on art, race, feminism, etcetera. I feel like I had started understanding the questions of race that I had never had to address as a black African. To walk into this conversation, dialogue, these queries and critiques, was so powerful. The books we were reading: bell hooks, Michele Wallace, Huey P. Newton’s Revolutionary Suicide, Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. The films I was introduced to: Paris is Burning, Maya Deren’s Divine Horsemen, Black Is…Black Ain’t by Marlon Riggs. All the material that we were getting exposure to was giving back to us. It’s like you were learning as you absorbed and listened and went to talks. And even at openings—you just looked at the work, that was the other thing. And having someone like Fred Wilson as a teacher was so important. So that’s what was happening when I was at Cooper Union, and that also made a lot of impressions on me. I think things have shifted from that moment, and we’re now in post-9/11, post-Bush, post-Black President time!

DW So, you thought this moment in the mid-‘90s with its provocative art exhibitions and gatherings in SoHo, was normal?

WM I thought it was normal! And then before I could tell, Thelma wasn’t even at the Whitney Museum anymore. And then I was off to Yale, and it was a whole other kind of discussion. Yale was like getting thrown back in time. Discussions about race and gender and institutional critique were certainly not as developed or tolerated. Up until then, my environment was exceptionally diverse and multicultural.

DW So, back to Cooper—what kind of work did you create? Because I notice that the body, when you talk about race and the figure, was important in your understanding the energy of this time period. Did you have ideas about looking at the body in a different way as a result of this political and cultural energy, or was it rooted in your earlier experiences in Kenya?

WM I think that I was witnessing how the body is politicized in art. I was always interested in the power of the body, both as an image and as an actual mechanism through which we exist and find out who we are. I was interested in what goes on inside, but also what people see you as. I was also looking at the history of the body, questioning issues of representation and perception. The body became the mechanism with which I was able to move my mind around all of these issues of otherness, of transplanted-ness as a young woman, my blackness as an African-raised black woman in New York City. It became crucial to me to use it as a pivot, you know? But then I realized that it’s also a trap. There’s something about the body that confines us, that disables us, and that prevents us from being immaterial, being invisible, being all of these things that maybe you want to be, because maybe you don’t want to stand out. I don’t stand out in Kenya. I’m just another Kenyan woman. But here, depending on where I am, I’m that girl, that Kenyan, black…whatever. So I realized what this body meant, at that moment, and that the discussion around the institutional critique of work by Fred Wilson, like “Mining the Museum,” or around the powerful, explosive, radical silhouettes of Kara Walker that I was involved in and witness to, was so important.

Black Lips from the Family Tree series. One of 13 mixed-media collages on paper, 19.25 × 15.25 inches. Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC. © Wangechi Mutu. Photo by Robert Wedemeyer.

But I also am obsessed with the body. It wasn’t given to me; it was something I came with by being athletic and having a fascination with dress/costume as a way to mutate. I think about the relationship between the femaleness of my body and society’s perception and expectation with me. I get how the body can be dressed up or masked. One can masquerade, and the body is a structure, an infrastructure—kind of like a shell that can move around and create different reactions, for whatever reason, to empower yourself, or, as I said, to disappear or transform.

DW But what about the freedom you have? I find it a really nice connection that, as a young woman you had freedom of movement, which is normally unusual for women coming as immigrants to this country. They usually stay strictly within certain roles, such as student, sister, wife and mother. So, it feels as if you felt—from my observation—that art school gave you certain privileges that most people don’t experience. Did you know it at the time?

WM I did, and at the same time I didn’t want to focus on it too much. The way I chose to come to the States was calculated and impulsive all at the same time. I didn’t give my parents a chance to think it through to the degree where they could say, “Actually, you’re absurd for trying to do this.” I basically got into school, found the funding, went through the motions. And I was like, “I’ve found the school, I have the funding, just please help me with the ticket.” They looked at me like I was nuts. And of course I’d been away in Wales for two years. I remember at the time, my older sister was trying to do certain things to further her education and she was getting a lot of, “Hmm, no, you shouldn’t do this and that.” I asked my mom, “Why won’t you just let her do this? You’re letting me go to New York.” My mother and I have a wonderful relationship where we’re able to talk about personal things big and small. We have a great dialogue. I said, “Why do you let me do it and not her?” And she said, “Oh, because you’ll be fine.” So without her realizing what she was saying about my sister, maybe, I got my answer there. My sister was a very good student, a very lady-like, studious girl who may have felt she couldn’t jump into the abyss or do the crazy things she wanted to do. I on the other hand didn’t really care what they thought and instead decided to do what my heart was drawn to with no map, no manual. So they were freaked out about my coming to New York—and in fact, I was too—because all I knew about New York was what I saw in films. But they somehow thought I would be okay.

DW In movies, right?

WM And newspaper articles. It’s not good news that makes news. I knew that I had “released” myself from my home in a way that made me very vulnerable. It exposed me, and I had to be careful, I had to be aware. But I was also raised in Nairobi and was thinking, “Okay, this is kind of like Nairobi.” You look where you’re going, you figure out where you want to live, how you’re going to deal with people, and those instincts did help me tremendously. I guess I was like that already. So that opportunity came and I took it and went with it. It was not unusual that I was in that situation, because I had been asking for this for a long time.

DW What’s your birthday?

WM June 22. I’m a Cancer.

DW It’s this ‘70s way of reading personalities, but that crab, that Cancer, is really moving all over…

WM I think so too.

DW I’m curious; you were born during the “Blacksploitation” period of filmmaking, so you didn’t grow up with those movies. What types of New York movies did you see? Did New York intrigue you? I know fashion intrigued you.

WM Yes, fashion intrigued me. But the Blacksploitation films weren’t available to me. The movies that were very New York to me were the break dancing movies—for example, that whole Beat Street, The Last Dragon, The Karate Kid, martial artsy sort of thing. New York looked rough and dirty and sinister, but also a lot of fun from our perspective in Kenya. But it was much bigger than us. We emulated things about New York, but we were like, “That’s too much.” Fame was another big show. I was obsessed with Fame.

DW What kind of music did you listen to? Who were your icons?

WM Oh my gosh, R&B and country music. Very Kenyan.

DW R&B and country?

WM Would you believe it?

DW They’re connected. It’s all about yearning and love.

WM Now, people are beginning to admit that. The entire world listens to country music without considering the racial, historical aspects of where and what it comes from. All that stuff? No, we didn’t think about that. James Ingram and Dolly Parton would be listened to by the same person.

DW What about Otis Redding? Was that popular too?

WM A little bit. But you had to be a bit more of a soul music buff.

DW Okay, so soul was different from R&B, as a connection.

WM Absolutely. The R&B then was more like Luther Vandross, Anita Baker, and a little bit of Patti LaBelle, but even she was a little funky, soul. There was a reggae hour on Saturdays in Nairobi; I remember listening to a lot of reggae music.

DW To Bob Marley?

WM See, as middle-class Africans, there’s a whole set of issues and things around contemporary black music, what’s hip right now, and what’s appropriate, that goes with religiosity and propriety. Persnicketyness, properness. I always say that and Fela was played on the radio but Fela wasn’t the kind of music you should have been listening to. My mom would mention that about Fela, “Oh, that Fela. That dirty music.”

DW (laughter)

WM Because he was this total rebel. He was like us; he was a middle-class African young man, gone—

DW —Very sexualized.

WM He went to school in the UK for a stint, came back, and turned crazy radical and self-aware, and then decided to do his own thing. Decided to be polygamous, to be against/critical of Christianity, which is not the way middle-class Africa behaves. Unfortunately.

DW (laughter)

WM That’s what made him radical. He became very politicized too, because his mother was very political. Which is actually why, I think, he understood what his role was. Anyway, we listened to Fela but it was not encouraged.

DW This whole fusion of the US and the Caribbean, and then Fela, that experience, I can see, also shaped your move to New York, not only your political but your cultural moves. Aesthetically, in terms of local artists, did you spend a lot of time with artists in Kenya? Was there an art movement there?

WM No, I wasn’t connected to any of the visual artists. A lot of the artists who were well known were older, male artists, mostly making paintings or two-dimensional work, very much attached to their folklore, and traditional Kenyan life, which was not anything that my generation was necessarily interested in or connected to as such. A lot of them were not raised in Nairobi. They had incredible knowledge of African traditions and mythology and stories, which we weren’t raised around. Which is a regret that I have.

A Shady Promise, 2006, Mixed media on Mylar, 87.5 × 108.75 inches. Private collection, New York.

DW When you say traditional life, what do you see as traditional life? Because we think hunter-gatherers. (laughter) Working and farming, and things like that. Also, curator Trevor Schoonmaker once remarked about your work, “trees have been used as indicators of location for specific events or spiritual forces, symbolically marking a space and a time for a particular type of storytelling…”

WM These are men mostly/only, who probably are in their 50s to 70s—Kivuthi Mbuno, Sane Wadu, Jak Katarikawe, Joel Osweggo—who basically had been taught by their grandparents, their elders—about their world mythology, folktales, stories, sayings, and parables. All this knowledge that is pre-European, pre-Christian, had been passed on to them. Very rich in lessons and the kind of allegory that brings out what people like to call authentic African imagery. And their paintings are amazing; they’re fascinating—but I wasn’t raised with that. I was raised with this almost futuristic type of upbringing. My grandmother knew these things but my grandmother in fact was Christian. My grandmother didn’t encourage this sort of teaching. Now she does a little bit because she’s seeing where this attempt to modernize and Westernize has gotten us.

DW How old is she now?

WM Ninety-three.

DW How about that. Fantastic.

WM I know, amazing. I just went to visit her, so I’m obsessed with and in full adoration of who she is. She’s a powerful woman, a little old lady, but very powerful. So these are the artists I was seeing because we’d go to galleries, Gallery Watatu, Payapa. In the contemporary Nairobi galleries you saw this kind of folkloric painting. I thought it was beautiful, and I got it, I saw why they painted the way they did. I understood the non-perspective flatness and the fusions of humans and animals and creatures, mashetani, spirits, deities—and how these things all existed together. Because in old tradition, in Kenyan tradition, the world is divided into different worlds that live separately. They are like the living dead, the living, the dead, the spirits who come to visit us, who are ancestors who are still around. All that stuff was real in their work, and you could see it. But the way my sisters and brothers and our friends were raised, this old-world tradition was not the world vision that we were exposed to by our parents. I didn’t see myself in these paintings. I didn’t identify as an artist when I saw that type of work because it didn’t seem like something that I could do. But leaving Kenya and looking back at Kenya from a distance, I realized—I can do something else because I am now of the present, and I’m of a different time from the painters I had seen. Also, I have a different set of images and historical references and experiences that are actually both relevant to this moment and a mixture of the past. Because there’s a whole lot of us, from this generation, that are broken off from our heritage in some way, that actually have a story to tell about what Kenya can be and how a present-day, contemporary African can actually exist.

DW So you create the new parables and oracles for it.

WM We have to.

DW Which is important because the decision to study at Yale—was that your decision, or did you study there because Robert Farris Thompson and Kellie Jones were teaching there?

WM My decision to study at Yale was based on a kind of pragmatic understanding of myself as a person who would have to exist outside of the small New York art community. People don’t know what Cooper Union School of Art and Advancement of Science is outside of the US. So I realized, if I didn’t live in the US, I would need a school with a name and one that provided an experience that could transcended that. So, very pragmatic in that way.

DW And bold, too.

WM Oh, gosh. (laughter) Crazy, more like it.

DW Just, “Yeah, I’m going to apply to Yale!”

WM Yes. I have to say, though, that at the time, there were a few black students at Yale that made that connection real for me. Sol Sax was there, and Edward Steinhauer. This Haitian young man was there, and my friend, Rina Banerjee, an Indian woman from New York. So there were students of color that were in communication with undergrads and younger art students here in the city. That actually shocked us. We were surprised, “Oh, you guys are there!” Of course they all told us the horror stories and how hard it was for them—but in our minds it wasn’t as foreign because of them and we weren’t as crazy as, maybe, they were, because we would be applying knowing that they had survived it. They made a Yale MFA palpable for us.

DW What kind of portfolio did you put together for your application?

WM Whoo. I had to jump and go even further than my Cooper Union one, for Yale, of course. I put together a portfolio that was mostly sculpture, because I was applying to the sculpture department. During my Cooper Union years, I realized I wanted to focus on sculpture. I wasn’t as impressed by or interested in how painting was being taught. And I didn’t feel like I could justify myself as a painter because I didn’t believe in painting as a form for what I wanted to do. I decided to focus on sculpture—it was not so much even that I wanted to make objects, but sculpture allowed me to discuss these other histories and languages that were not part of Western art history. Contemporary sculpture was a space where I could talk about contemporary and past cultural trends of Kenyan origin. I could discuss post-colonialism, syncretic languages, pre-colonial spiritual aesthetics, and the development of new ways of looking at things historically, artistically, culturally, in a way that painting didn’t allow. I felt like painting was about painting—and painting always came back to the history of painting, which was Western painting.

Red Armed Tree from the Family Tree series. One of 13 mixed-media collages on paper, 19.25 × 15.25 inches. Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC. © Wangechi Mutu. Photo by Robert Wedemeyer.

DW What type of materials did you work with at that time?

WM I basically picked up things I found around the art department, anything that I could find around me. I was really broke for years, as an art student, and so I almost had no choice. It’s not even that I was trying to be hip or whatever. I literally would find something in the street, appropriate it, and be like, Let’s extract meaning out of this somehow. There was a moment when I was trying very much to use materials and objects and items from Kenya, but I found it tremendously difficult to work with those because the translation of objects is different from the translation of an image. And so I would find myself having to explain why this particular object was relevant, where it sits in the cosmology of our existence, as a people, and why people should value it or think about it. That’s not what I wanted. I didn’t want to dictate to the viewer how they should see my work.

DW Were you stereotyped as the “African artist” and as a result did you have to create work from that?

WM Maybe. Yes. You know, I’d love to hear more from my colleagues, as to what I was seen as. Because people didn’t know—one of the things about being in the States throughout my twenties and thirties was that there weren’t that many Africans around in these institutions. So I don’t think people knew what to expect. And they never thought, Oh there’s an African. What an African is, in the mind of Americans, is very different from what Africans are. So that wasn’t the issue. Also, I had, at the time, more of a British Nairobi accent. Now I realize that I speak many different Englishes and I adjust them quite a bit, but that’s another issue, an interesting problem. But I was worried about stereotype, and I’ve obsessed about stereotype for that reason because it’s there, and it’s followed me. It follows people and things, and if you’re doing interesting things and find yourself in circles or surrounded by people who are not like you, you’re always running up against stereotypes, dealing with them ten steps ahead, watching people stereotype you and trying to figure out how you can either move away from them, or draw them closer, or just get out of the situation. Or actually just transcend it, somehow. So that has always been a fascination, problem-slash-subject matter of mine. I decided to turn stereotyping into subject matter of my work.

DW I’m glad we’re talking about that. We’re going to move to that next, but—influences. Who were your early influences, here in the States, and then internationally?

WM In the States, I remember moments where things blew my mind. When I first learned about Ana Mendieta, that was just like, wow. Mendieta fascinated me, that there was this legacy of who she was and when she came and this power in her work. At the same time there is very little evidence of her anymore. And then I loved Frida Kahlo from the beginning and somehow identified with her.

DW And here you are. Roots. Trees. You have both, and then, going back to your dad.

WM Yeah. Absolutely.

DW What about [the] work with photography because I know you posed as a model. Did you pose also for painters?

WM No, not for painters or people who were drawing. But I remember the first time I saw a Claude Cahun show—I think it was at NYU, believe it or not.

DW It was.

WM I loved that exhibition. And the first time I was introduced to Coco Fusco’s work, the Two Undiscovered Amerindians piece was another moment. I was like, Now this is it. I studied with the Afro-jazz musician, Michael Veal; I took his music class at Yale. That was incredible. We were studying rhythm as a way of understanding cultures in his ethnomusicology class. So we were looking at these Indian rhythms and then breaking down Thai Gamelan rhythms, and how these rhythms have so much to do with architecture, with their understanding of math, with their type of existentialism, all the way from the deities to the mortals. It was incredible. I remember my assignments were all visual. You were told: You can write, you can record things, or you can do whatever. I did these visual assignments. I created diagrams in the form of a fractal to explain the rhythms and patterns and relevance. John Schwed, also, was one of my teachers at Yale. One thing I studied with him was the origin of English. I bring that up because it was at that moment when I realized the fact that so many cultures and so many things that seem whole and intact have actually been created from all of these bits and pieces and parts and are essentially Creoles. In fact their wholeness is held together by people’s consensus and ability to understand and add to it, and English is that. English is this language that everybody has added to and created over the years, including those who were colonized by it.

DW That also happens with the creation of your art.

WM And that’s exactly—I remember that moment, thinking, I love this idea.

DW It’s a new thought for me, this understanding of different cultures through rhythm. I want to think more about that as we talk about your work.

WM Sure, sure.

DW In terms of your workspaces, you are based in Brooklyn, correct?

WM Where we are right now, in Bed-Stuy in Brooklyn, and I’ve been working in this studio for close to eight years.

DW Why this historic neighborhood? How did you discover this beautiful brownstone, at that moment of time (2005) when most people ...?

WM —Were not necessarily running to live out here?

DW Mmm-hmm.

WM I have a friend who lives here and he had bought a brownstone. I went to school with him at Cooper Union. His name is True. It used to be David Riggins. True bought a brownstone here years before I did. He’s very conscious, sort of black nationality kind of thinker. I had lived in Brooklyn already in Clinton Hill and Williamsburg. I always lived in neighborhoods before they were gentrified, not because I was trying to but because that’s what I could afford.

DW And then you change the neighborhood when you move in. (laughter)

WM Actually, no. It would change after I left. (laughter) “She’s gone, now let’s—”

DW But you left an influence.

WM Yeah, there we go. I shared a living space next to Biggie Smalls’s apartment, where his mom lived too actually, in Clinton Hill. When that funeral happened, it was right outside of our apartment, in the brick house next door. Fast-forward, I’m living in Clinton Hill, renting an apartment, working in a large one-bedroom. My work is getting bigger and more work is coming out of me than I even imagined, and I got another space in the same building. I’m sitting there thinking, I’m paying this incredible rent, and I could afford a mortgage with this. I don’t know anything about buying a property, but in theory, I realized, it was a mortgage price. So I said, “Why don’t I just try to get a place?” Also, at the time, and compounding that, I was addressing the fact that my immigration position, my case was getting more knotted up. I was running further into my visa issues and I think my deeper mind was saying, “You need to find home. You need to buy. You need to make home.” My more practical mind was saying, “You need to get yourself a place here so you can be responsible financially, so you can condense your time.” I was also going to residencies that were far away from where I lived at the time. So even though I had a little studio at home, and I worked there, I was at Jamaica Center for the Arts and then I applied to the residency at Studio Museum. I was often so far away from my studio and my house; I would be getting taxis or trains at the most absurdly late times. I needed to find one place where I could do everything: work until 4 AM, go upstairs, go to bed. And the idea of getting a brownstone to do that had always been appealing to me; I’d seen people who live and work in the same space, like two floors where they live and work. So I went out on a limb; I asked my friend True to help me, and he found a couple people who were selling and he trusted them and we looked at places, for a little while. And none of them made any sense. I was like, “I’m going to stay where I am.” And then one day I get this call, out of the blue, and this woman says, “I have a place for you.” I told her, “I don’t care about the subway so much, because I’m not going to be going in and out of the city. I’m going to work, work, work, and then when I have to go to the city, I’ll take a car, but don’t worry about vicinity.” Certain things I wanted, like grocery stores. So she showed me this building, and I said, “What is wrong with it? There’s nothing wrong with it?” And she said, “That’s what I think. If you don’t get it, I’m going to get it.” I don’t know if she was just being the best salesperson I’ve ever met in my life. Then I had a friend come in and look, then an engineer and an architect, and they all said it was fine. There was one little structural problem under the stairs that could be dealt with very easily; that was it. They said, “Everything is fine.” And I was saying, “What’s wrong with it?” because also, at that point, the price just seemed totally reasonable. Now it’s actually obscenely low; I know you can’t find a building for that price. But at that time it was reasonable. So I got a place.

DW Was it a family selling it?

WM It was, one family who lived here, but they rented to a friend too. So it wasn’t broken up, too much. Obviously, Mr. Uncle So-and-so had fixed this and that, so it was all hodge-podgy but that wasn’t too bad.

DW We love those uncles in our family.

WM (laughter) Oh, my goodness. You open those walls and you’re like, Oh my God. He said he knew what he was doing. And they believed him! (laughter) But it functioned. It was good. I didn’t have to do a ton of work to live here. I think I renovated for two months and that was it.

DW How were you able to afford it? You left Yale, did you have a gallery? Were you able to sell work?

WM Yes, I had a gallery before I got it. My LA gallery was representing me.

DW How did they find you?

WM Susanne Vielmetter found me through a friend who came to see my work at the Africaineshow at Studio Museum. She actually didn’t see the work live, she went by word of mouth. This collector, Rebecca Stuart, who was very, very enamored with my work, and had already bought something, told her about me. So then Suzanne came to see me and we started our conversation. She flew me to LA and I saw her space, because we were planning to do a small show. She realized that I was creating a lot of work, and was ready for more than she was offering. So she said, “You know what, instead of giving you a portion of the gallery, let’s do one, big, solo show.” This was in, I think, 2004. I’d been out of grad school for four years, which at that time felt like a lot of time, but I couldn’t find a New York gallery that was interested in me. It took my LA show, which had these incredible reviews and sold very, very well, for New York to wake up and be interested. I remember the buzz that happened, right afterwards. There was this connection among certain people who really respect the Studio Museum, and obviously collectors and galleries, back and forth. And all of a sudden it was like voom! They descended upon me and I was in this bizarre position of having to translate all the attention.

DW Mutu! (laughter)

WM Yeah, it was actually a very unhealthy situation to be in. It throws you off-kilter. You’re in this position where everyone is pursuing you but you’re not sure how exactly to address that. You don’t know who wants what and why. In fact, you don’t have the tools because the last thing they teach you at art school is how to understand which gallery is best for you and what the art market really is.

DW And you were able to save money from that period to buy this place?

WM From that period, I saved a lot of money. I was way more frugal than I am now. (laughter)

DW What type of work were people looking at? You said that you were robust, or making a lot of work.

WM Around 2002, I began making a lot of work on Mylar—collage works, always focused on these subjects that were female, somehow transforming into or from cyborgs or chimeras of animal, plant, and human mixtures. These sort of mythological creatures: in poses, in action, in dance, caught in motion in their worlds. During that period, there was a lot of use of fashion magazines and fashion poses in my work, but they were tweaked and distorted just enough that you understood where these imagined figures came from. These creatures as I’d created them obviously were not something that would ever be found in their publications of origin. I’ve since moved into other ways of representing the body, but at that time it was a lot of taking these posed, very fictional females and extracting meaning out of them and squeezing a new discussion into them.

A'gave You, 2008, Mixed media collage on Mylar, 93 × 54 inches. Private collection, New York.

DW So what kind of research do you conduct on these references, these female subjects? Do you use Vogue, or fashion magazines, or National Geographic?

WM I do use Vogue a little bit, as a place to find the material. I absorb the information in there pretty quickly; it’s not that deep, and it’s all seasonal. But I do love using those magazines: the type of paper, the type of photography, the scale of bits and pieces in there, the jewelry, the eyes, the animals are perfectly photographed and printed.

When I am tackling a new project, I research things deeply. For example, let’s talk about the present project I’m working on, a video work called Nguva. Nguvas—water women—as they're called, in Kenya. Nguvas are female, fish-like creatures. Sirens, essentially, that have both a terrestrial and an aquatic existence. I don’t know the mythologies of what sirens or mermaids do elsewhere, but in our part of the world, Nguvas live in the ocean, but also come out and pretend not to be sea creatures. They trick people. They are able to find human weakness and utilize their power to drown people, to drag men into the ocean. They’re frightening and powerful because sometimes you are unable to distinguish them from real women. In fact, that’s where their power comes from, because a weak character might be convinced by this woman, by her face, her features. And then, before you know it, you’re walking out into the watery wilderness and into the water with her.

I’m obsessed with them because I love the ocean, I love swimming, but I’m also very, very interested in the fact that where I come from, they are considered to be real. I tested this when I lived on the coast on the island of Lamu, and the residents would tell me these stories, and I would sit there, like, I have to go home alone, why are they talking about this stuff? And then, after I left Kenya, it was years before I went back to hear these things again. This time my family and I went to the coast, and I was asking the lady who was helping to look after the babies, about the ocean women. And she’s like, “Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, I saw one the other day.” And she just got into this story, as if she’d just encountered this celebrity sea character. This is how it is.

DW So is it hyper-real, is it dream-like?

WM You know what, Deborah, we have these agricultural shows in Kenya. They’re like harvest fairs and people bring the biggest cow and the most plump cabbage, and they display it all day. But these fairs also have the circus freak side to them. That’s where you can see something like a double-headed calf or a bearded woman, that kind of thing. So the babysitter said to me, “Oh, they’re going to bring her for the show. You should go see her.” And I said, “What do you mean?” She said, “Oh, she’s there, with her tail. And the thing about this one is that she talks to people.” So I’m asking her, “So you’ve seen her?” She’s like, “Yeah. She’s scary. I wouldn’t take the kids there.” This is the power they hold and why I’m fascinated by Nguvas and fascinated by this kind of creature. For me it represents something even more significant, which is a belief system that actually works and is intact, and is held together by the people who understand that language, and who live within those parameters and those worlds. And that is, for me, so key, because I think we’re so immersed in this world of one-way of thinking, which is often based on Western scientific rationality, which I think has incredible importance and has its place. But I don’t think it is the be-all-end-all knowledge base for everything. I don’t think it’s a way of understanding everything that exists around us. There are other things. I’m not saying that this thing is real but I am saying that there are other ways of understanding our universe, and our world, and our humanity. And we’ve discounted those things. We’ve—often for modernity’s sake, as a race, as humans, as a colonized people, as colonizers, however you want to say it—we have disrupted those ways of thinking because it doesn’t jive with the new logic, with the Enlightenment, with scientific development. But there are ways of thinking that actually promote another way of being conscious, and being empathetic, and being human, and being intellectual that I actually think are worth looking at. Nguvas are actual animals, believe it or not. The word is also used to describe this manatee-like creature, which is called a dugong. Dugongs are close to extinction in our part of the world because their meat is of the sea. Manatees too are vegetarian sea creatures. So they have a cow-like, beef-like taste but because of the sea, I think, they’re even tastier. With Nguvas, when they’ve been found, and a fisherman catches them, they know they’re not supposed to kill them, but sometimes they do because their meat is apparently so delicious. There’s also a sexual aspect because they’re considered to be these sea nymphs. I could go on forever, but men who catch a Nguva—this is a very Muslim area, the coast of Kenya—are advised to go to the mosque, to purify themselves and to swear that they didn’t have any sexual relation with this creature. So there’s this unbelievable, amazing language behind what these creatures mean.

DW That’s what’s so exciting about your research, though. Your visuals are seductive; the research seduces you, and then the storytelling.

WM And it’s still driving me a little bananas. I’m trying to wrap my head around it, sitting here in New York City. So anyway, the Nguva also represents to me this almost extinct creature in an almost extinct culture.

Yellow Bird Head from the Family Tree series, 2012. One of 13 mixed-media collages on paper, 19.25 × 15.25 inches. Collection of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC. © Wangechi Mutu. Photo by Robert Wedemeyer.

DW Was scale or the size important to you? You have a lot of large pieces and pieces that we walk into and around, and then sometimes you have really small pieces that you want us to penetrate, to look through. So these Nguva, are they large? Is it “Nguva”?

WM Yes, N-G-U-V-A. The collage works are going to be life-size. My work increased in scale when I realized that I wanted people to enter the worlds or to see them almost like dioramas— these places that they could be immersed into, with their own social structures and their eco-systems. So that’s why I work relatively large, and I think about that. But I also have these smaller works that tend to be very much about the source material. So if I’m working with postcards, I keep it postcard-sized, because I’m trying to discuss the idea of postcards and photography and the history of postcards. Especially as a Kenyan whose country is over- exoticized, over-visited, in fact discussed through postcards, through travel, through the idea of—let’s go for a safari and look at these people, this is who is in Kenya. But that is very important for me, my postcard series is an ongoing investigation. There’s also work on printed illustrations of medical diseases that I’ve done, especially diseases of the female genitalia. That’s a bit of an ongoing series; I still have prints that I’m working on. And I also keep things in scale to the magazines that they come from. So there’s certain work that you’ll see that’s about the size of the large glossies, the small magazines, the pornographic magazines. It’s about thinking about that format and what that format means and our expectations when we open these magazines. What we think about ourselves and other people as a result of the obsessive pawing-through, these disposable forms or versions of our culture, as it is, because they’re very fast interpretations of who we are. Which I actually think is why they’re so honest. You see, these magazines aren’t meaningless but, in actual fact, they very accurately record what we are looking out for at this moment in time. This is what we want to represent ourselves as, and this is who we care about, or that’s how we want women to look. So that format is important to me for that reason.

DW I wanted to know how you want us to be transformed by your work. But it’s not that you necessarily want us to be transformed. You really want us to experience different points of entry with the world. You stated in an interview with curator and professor, Isolde Brielmaier, that “the body in your work is a point of departure.” Do you still see the body as a shared “space and landscape”?

WM Yes.

DW I love the point that you made about the postcard and the safari. They’re journeys throughout that experience of looking at your work. And then it also ties into your own journey, as you left, and then as you’re revisiting and going back. Here, also, with the aspect of models, and then your Portrait of the Artist. Love that piece! I want to see it large, I want to walk into it. I love the choice of symbolic objects used in the photograph—like the gourds, and then the fresh fruit, and they are all consuming. I think of Fellini’s films, you know what I mean? And I think of Monet, and the older references that we have, and then going into work of contemporary artists like Carrie Mae Weems.

WM I just thought about Carrie, just this second, before you said that.

DW Right, who is also referencing art history through her artwork.

WM I remember seeing her work for the first time, and thinking, Oh my goodness, this is just slightly off of reality, and so poignant. And so cinematic. I find her work to be like cinema stills, but all about an investigation of the self, and in that way allowing all of us to discover and discuss who we are, and how we’re seeing. I love her series. Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried. I think I actually cried.

DW Talk about how you constructed the self-portrait, Portrait of the Artist. It looks like you worked on this idea for a long time to build this ideal figure of an artist. Has it been collected by anyone?

WM No. Because I didn’t ever position it that way. I was trying to make fun of people who love to exoticize and fantasize about me as this creature from another world.

DW No? I have not seen it other than as a document in a publication and I’m curious why.

WM I had this distinct feeling at that time—and I still do—but then I was so, so bothered and obsessed with the fact that people didn’t quite know how to read me, and place me, and kept confusing me for one or two other black female artists, and when they didn’t, it was this other reading. So I said, “You know what? I’m going to take people on a little ride here.” But I never do that in this cocky way, where I’m planning to lose anyone. Because I’m in it with them, you know? Let me have fun with this. So I wanted to create a very, very exotic (and, at the same time a bit erotic, without being too stereotypical) image of myself, as this thing, this person. And I wanted to put myself in this world. So I was projecting this tropical environment that actually was in my back yard. It started drizzling. We were using a huge, large-format 8x10 camera, and it was frightening, because this is an incredibly expensive piece of equipment and the drops start coming down, but the rain helped moisten everything, which was perfect. I had a rope across the garden, where I’d hung all of these tapestries and curtain fabrics, even these silks that implied Orientalism, and then I had these fruits. I really wanted to push this idea of the succulent tropical fruit. The eroticism of that was interesting and important to me, but also the indulging of it, the eating, the consumption. This was a stinky fruit by the way, it was this disgusting smell of dirty drawers.

DW It didn’t look like it. (laughter)

WM It was a Chinese fruit, the size of a human head. It tastes good, apparently. I didn’t taste it, but it really smells horrible. Of course I love that idea. And then I had these calabashes, and horns, and bones and things. And with that I was also playing with other art historical references. I thought about O’Keeffe, and Frida Kahlo—but then I was also thinking about things that people think of when they think of tribal, authentic, shamanistic ideas. They think of the bone. I love and hate Eddie Murphy’s depiction of Africans in Raw, the reality of where he’s going with that. And I do this weird thing, I don’t know if it works. It’s like I make gumbos. I put everything in and make sure it simmers just right, and then I try to see if it tastes right, because it’s hard to push a lot of things into one thing and still taste distinct flavors.

Root of All Eves, 2010, Mixed media, ink, paint, collage on Mylar. 96.75 × 58 × 2.5 inches. Private collection, Toronto, Canada.

DW Well, it’s successful, because I feel like I’m panning across and looking through. In the next few minutes, let’s talk about words: icon, beauty, the experience of beauty. I see a sense of empowerment. I thought about Sarah Baartman who was displayed around 19th-century Europe like an exhibit. Sarah Baartman, who was also known as the “Hottentot Venus” was one of the early women to come out of Africa; in Europe her genitalia were documented and photographed [as if she were a specimen]. She is still mythologized in many ways. We can imagine imagery from your work connected to that. I’d like to hear you talk about this discussion about that wounded body, the wounded beautiful body of Sarah Baartman that you also reengage us with in the women of the sea—that mermaid, that moment of sheer existence. These two extremes—the imaginary and the real—and then your place in that, for us to imagine that becoming real and three-dimensional.

WM The black female body has been violated and revered in very specific ways by the outsider—Europeans, especially. The issues that pertain to race: pathologizing the black mind, exoticizing and fearing of the black body, objectifying the body as a specimen, or a sexual machine, or a work animal, or relating the black body to non-human species as a way to justify cruelty… All these are practices that are placed excessively upon the black female body. My personal belief is that deep inside all humans know that our ancestors were black Africans. The connection to Africa is obvious, even if it is an instinctual, intuitive awareness. Those who reject Africa do so out of ignorance, learned and acquired, but also because of how far away they’ve moved from the core, “original” traditions and languages of their ancient ancestors. The destruction and colonizing of pre-Christian traditions in all societies is one of the last, most frightening denials of Africanism and the beginning of the worst denials of the black female body as a body of grace, power, and ancient genes. Racism, deep inside, is a killing of the original mother; a murdering of the people who begot all mankind. It’s a perverse yet clear desire to destroy that female who you no longer desire or feel you require and value. In the meantime, the body is put to work, devoured, tortured, broken, mutilated, and then prepared for display as an artifact, a totem, a specimen. Even in this state of containment and capture, our body is valued and worshipped—yet feared and reviled.

One Hundred Lavish Months of Bushwhack, 2004, Cut-and-pasted printed paper with watercolor, synthetic polymer paint, and pressure-sensitive stickers on transparentized paper, 68.25 × 42 inches. Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

DW Black models and figures are almost absent in contemporary art and even in popular fashion magazines. I’d like to hear your thoughts about this and how you are re-inserting these images from pin-up girls to imaginary figures. You also insert white skin, blond hair, and red lips, and place these cut-out body parts and merge with black skin. I find your props essential, from stilettos to lace—provocative props to connect a myriad of experiences to explore gender-based stories. More on that process…

WM I’ll tell a little anecdote. I first saw Grace Jones, and I’ve mentioned this in other contexts, on a German TV show called Pop in Germany that we used to watch on Saturdays in Nairobi. This show was funny because it had very cheesy German house/pop music. We only had one channel, so we just watched whatever was on. But this time Grace Jones came on with a leopard-skin cat suit. That was the first time I’d seen her and the first time I’d seen that kind of costume. We used to watch Solid Gold and my parents would always complain about how raunchy the thong costumes were. But this was the first time I’d seen this kind of costume in active use and it blew me away. I couldn’t wrap my head around this woman because she was certainly performing, but there was something about Grace Jones acting out this leopard, feline creature with her butt in the air and her tail swishing around—because she had a tail connected to the costume—it was like they’d painted this thing on her. You could see everything and she’s obviously got this incredible body. But leopard skin is the one animal skin that denotes power, leadership, often masculine and male power. So people like Mobutu Sese Seko wear it.

DW Kenyatta, yeah.

WM Kenyatta wore a hat and cape with leopard. It’s one of the most elusive of the big cats that we have, and seen as very powerful because it kills these big animals and drags them up into the trees. You can’t find a leopard; it’s always up in the trees or hiding. So there’s an understanding of what leopard skin means. And I knew then too that it’s got this contemporary, hip fashion, super-sexy reading. I wasn’t aware of how much leopard skin was utilized in the ‘60s and ‘70s, for fashion.

DW I grew up with my aunts wearing that print.

WM I didn’t know that.

DW My aunts still wear it. They’re in their eighties.