STUDIO POSES: PHOTOGRAPHS BY CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI AND KIKI SMITH

Photographic explorations by two of the century's most innovative sculptors of the human form.

DAVID FRANKEL

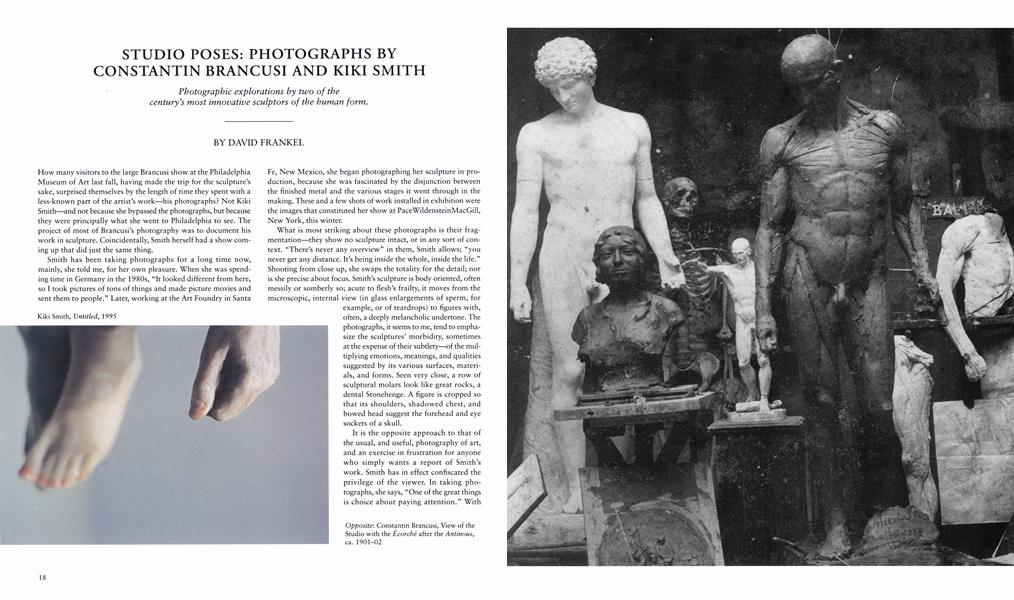

How many visitors to the large Brancusi show at the Philadelphia Museum of Art last fall, having made the trip for the sculpture's sake, surprised themselves by the length of time they spent with a less-known part of the artist's work—his photographs? Not Kiki Smith—and not because she bypassed the photographs, but because they were principally what she went to Philadelphia to see. The project of most of Brancusi’s photography was to document his work in sculpture. Coincidentally, Smith herself had a show coming up that did just the same thing.

Smith has been taking photographs for a long time now, mainly, she told me, for her own pleasure. When she was spending time in Germany in the 1980s, “It looked different from here, so I took pictures of tons of things and made picture movies and sent them to people.” Later, working at the Art Foundry in Santa Fe, New Mexico, she began photographing her sculpture in production, because she was fascinated by the disjunction between the finished metal and the various stages it went through in the making. These and a few shots of work installed in exhibition were the images that constituted her show at PaceWildensteinMacGill, New York, this winter.

What is most striking about these photographs is their fragmentation—they show no sculpture intact, or in any sort of context. “There’s never any overview” in them, Smith allows; “you never get any distance. It’s being inside the whole, inside the life.” Shooting from close up, she swaps the totality for the detail; nor is she precise about focus. Smith’s sculpture is body oriented, often messily or somberly so; acute to flesh’s frailty, it moves from the microscopic, internal view (in glass enlargements of sperm, for example, or of teardrops) to figures with, often, a deeply melancholic undertone. The photographs, it seems to me, tend to emphasize the sculptures’ morbidity, sometimes at the expense of their subtlety—of the multiplying emotions, meanings, and qualities suggested by its various surfaces, materials, and forms. Seen very close, a row of sculptural molars look like great rocks, a dental Stonehenge. A figure is cropped so that its shoulders, shadowed chest, and bowed head suggest the forehead and eye sockets of a skull.

It is the opposite approach to that of the usual, and useful, photography of art, and an exercise in frustration for anyone who simply wants a report of Smith’s work. Smith has in effect confiscated the privilege of the viewer. In taking photographs, she says, “One of the great things is choice about paying attention.” With sculpture, though, that choice usually belongs to the spectator, who can walk about the work and pick any number of angles and distances from which to look. By photographing her sculpture, Smith takes that luxury away; she wants it for herself.

On this level Smith’s and Brancusi’s photographs operate similarly. In a catalog essay for the Philadelphia show (which was co-organized by the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris), Friedrich Teja Bach firmly establishes the conceptual integrity of these images—the way Brancusi uses the photograph as a two-dimensional tool with which to analyze and explore his three-dimensional objects, and also to explain them, by framing them in controlled circumstances of context, position, and light that feed our understanding of the artist’s thought. Looking at Brancusi’s photographs, we may feel that we glimpse how he himself imagined the sculpture’s life— that we are to some degree seeing the work as he saw it. Like Smith, he is directing our perception and our response.

Overall, though, the idiosyncrasy of Smith’s approach is only underlined by the comparison with Brancusi, and this is in part because, absorbed though Brancusi clearly was with the camera’s aesthetic possibilities, the genesis of his photographs lay elsewhere: as Bach writes in the

Philadelphia catalog, “Brancusi’s photography began as a way of showing his work to interested persons who lived away from Paris.” Elizabeth A. Brown, in her book on the subject, spells out more plainly what Bach means: “Most often Brancusi’s reason for taking a photograph was market-driven: he needed a reproduction of a new piece for a potential buyer.” Indeed, Brown adds, several of Brancusi’s photographs “were printed on postcard stock, allowing the artist to send pictures to distant patrons with a minimum of fuss.” Brown also understands how Brancusi used photography to disseminate an image of himself as artist: he “took and released several photographs of himself relaxing, often with a cigarette positioned rakishly in the corner of his mouth, the image of the sexy bohemian. He presents himself as a dashing outsider, like a character from a Hemingway novel. . . . The intention is ... to influence the way an art audience would imagine his work and life.”

So, where Smith literally takes her sculptures apart in her pictures, Brancusi evokes an encompassing gestalt. Carefully placing and lighting a work, he will shoot it in its entirety, making an image that stands as a neat conceptual package. He will also take broader but equally careful shots of stretches of his studio, and of the array of objects that pose there; and these photographs eloquently phrase that place in the cadences of a romance, a Modernist-artist fable. They seem, in other words, to demand a Vanity

Fair-type caption about “Brancusi’s legendary studio in Montparnasse.” In one self-portrait showing Brancusi at work, he is brightly lit from below and to the side, so that tall shadows climb the walls, overtaking his upper body and the tops of the works clustered around him. The effect is dramatic, worthy of, say, the Josef von Sternberg of The Scarlet Empress. It’s undercut some, though, by the fact that it throws the surface Brancusi is working on into an improbably and impractically deep gloom; which reminds me of watching a pop group playing, or rather, lip-synching, on TV once, and noticing that the guitarist was accidentally strumming his tie.

Brancusi’s photographs are often convincingly grand, as when he shoots bronze and taller plaster versions of the Cock, all receding and reverberating with Himalayan distance and range, and all leaping in sheets of fine grays toward the light. His self-portraits, to their credit, can show a sly sense of humor: the famous one in which an Endless Column seems to grow out of his head is as funny as it is symbolic. There is, though, an element of calculation in these images—an alertness to commerce, and to the good opinion of Brancusi’s public, and of posterity. That current in the work hardly cancels its aesthetic strength and its arthistorical interest, but certainly coexists with them.

. . . [Smith’s] images, like Brancusi’s, are analytic, if in a reflective kind of way that seems to obscure as much as clarify, worrying at and denying the effect the sculpture might have by itself, or in a group.

Smith, on the other hand, had no audience in mind when she took her photographs, which she calls a “secret hobby.” Working, she says, by intuition, she photographs because “it’s so pleasurable to do. It’s nothing I think about that much.” Yet her images, like Brancusi’s, are analytic, if in a reflexive kind of way that seems to obscure as much as clarify, worrying at and denying the effect the sculpture might have by itself, or in a group. Photographing a pale wax figure, for example, Smith frames to crop the torso out completely; from the top of the picture, one hand and, more distantly, one foot hang down like stalactites. The method recalls the various surgeries of Surrealism, but where that work often has a streak of cruelty, this is more like commemorative or funerary art, and implies a sober sense of mortality. For Smith, images like this one “float between alive and dead, fake and natural.” Yet their mourning quality is qualified by the coolness of the abstracting impulse by which she cuts up her work, and a body, this way.

Smith traces her taste for “looking at the details to make the whole” to her father, the sculptor Tony Smith, who, she points out, combined small components into larger works. But there’s also an immediate charge: “There’s something really sexy about removing things from life’s space. It’s fetishlike. You get to control it.” Asked about her motive for taking photographs, Smith says she’s “probably just cannibalizing” one set of works to develop another. Applied to sculpture that has the sense of physicality that Smith’s does, the word has a certain resonance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

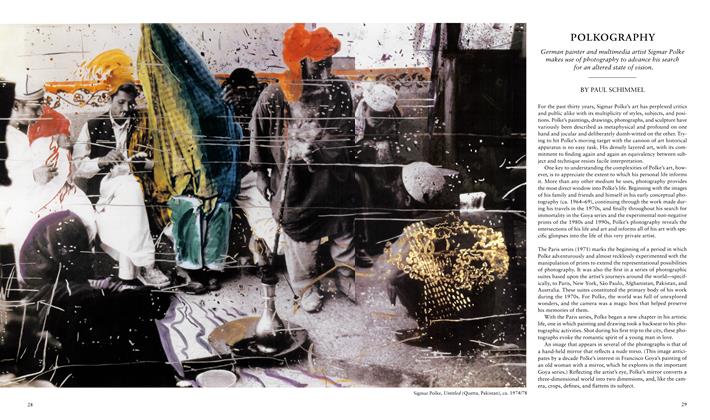

Polkography

Fall 1996 By Paul Schimmel -

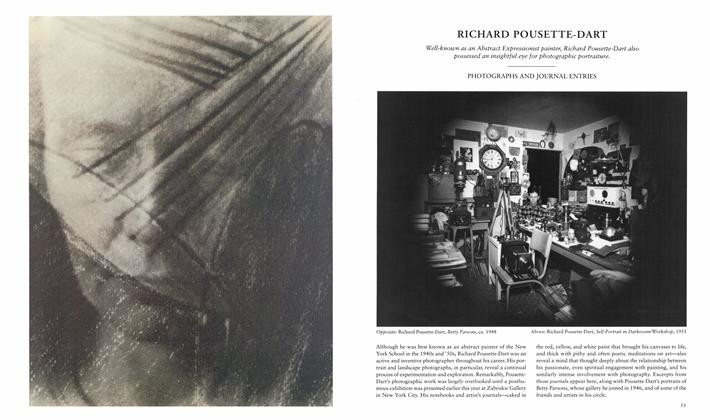

Richard Pousette-Dart

Fall 1996 -

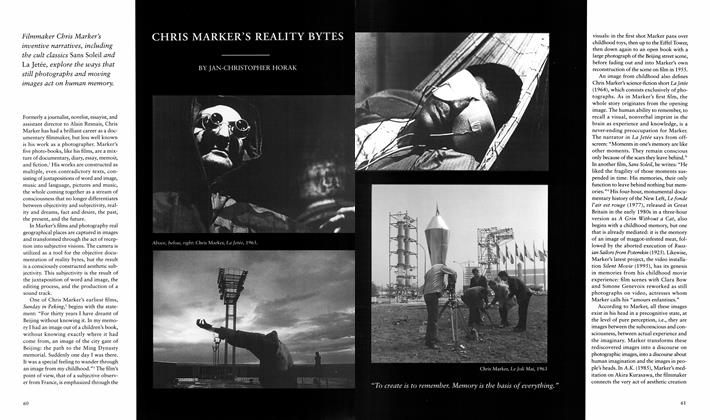

Chris Marker’s Reality Bytes

Fall 1996 By Jan-Christopher Horak -

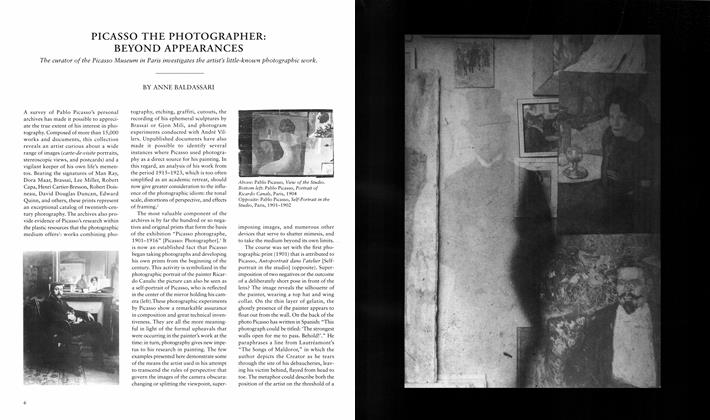

Picasso The Photographer: Beyond Appearances

Fall 1996 By Anne Baldassari -

Dark Mirror: The Photographs Of Edvard Munch

Fall 1996 By Charles Hagen -

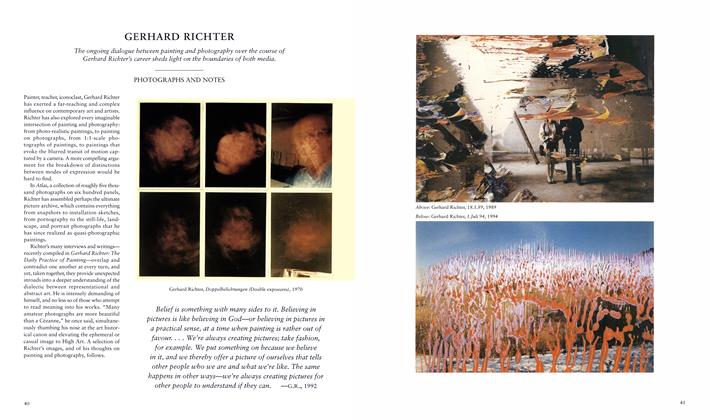

Gerhard Richter

Fall 1996

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

David Frankel

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasB's Make Honey

Fall 1990 By David Frankel -

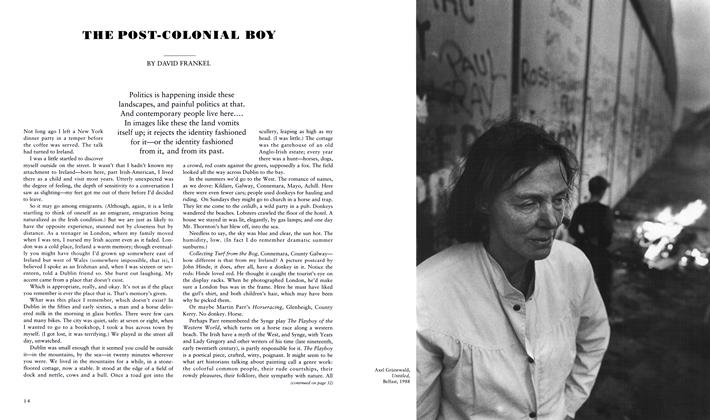

The Post-Colonial Boy

Winter 1994 By David Frankel -

Work And Process

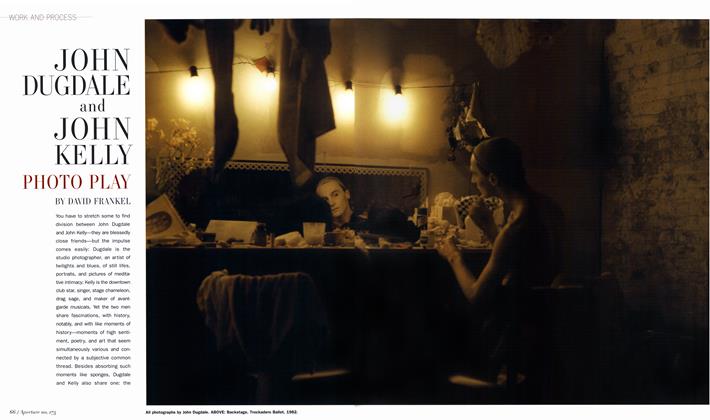

Work And ProcessJohn Dugdale And John Kelly

Winter 2003 By David Frankel -

Mixing The Media

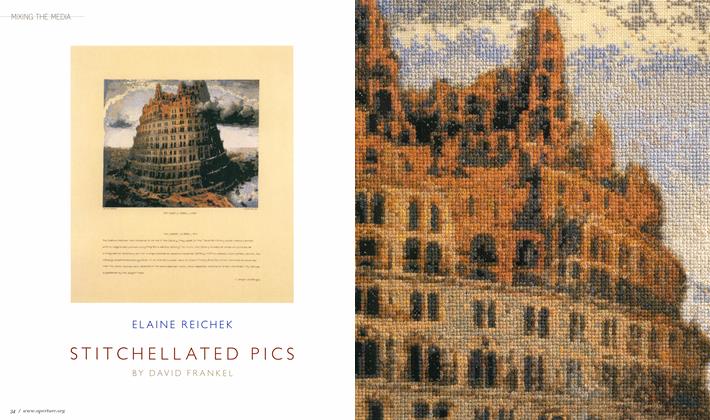

Mixing The MediaElaine Reichek Stitchellated Pics

Summer 2004 By David Frankel -

Mixing The Media

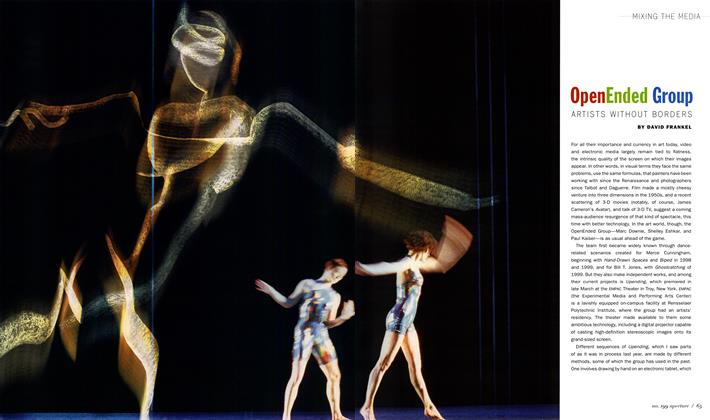

Mixing The MediaOpen Ended Group: Artists Without Borders

Summer 2010 By David Frankel