'This picture haunts Daddy': 9/11 generation finds its voice

- Rutgers students studied 9/11 and interviewed children who lost a parent

- Kids who had never told their stories opened up to someone close to their age

- They described paralyzing loss and a struggle to return to normal

- The stories appear in New Jersey media outlets on the 10th anniversary

New Brunswick, New Jersey (CNN) -- Megan Schuster grew up with September 11. Like others of her generation, particularly kids from the suburbs that surround New York City, she learned too soon about fear and loss.

At home and at school, where she was in the sixth grade, she saw adults sobbing and didn't know why she felt so scared. But 9/11 was a terrible event that happened around Schuster, not to her.

She would have to wait until she was nearly grown, a junior in college, to really understand how September 11 changed lives and tested the human spirit.

The lesson came through three sisters and a snapshot. Schuster still gets goose bumps when she tells their story.

Taken during the summer of 1982, the image of the wiry young man on the steps is fading now. He has curly brown hair, sparkling dark eyes and a mischievous smile. He was Timothy J. Hargrave -- T.J. to his brother and friends, "T" to Patty, the girl he'd been sweet on since grade school and later married.

Hargrave was 38 and a vice president at Cantor Fitzgerald when he died at the World Trade Center during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The company lost the most workers that day -- 658 -- and many of them left families behind in New Jersey.

Read a behind-the-scenes take on putting together this story

With her dark curls, Corinne, the oldest of his three girls, resembles the man in the picture. She was 10 when she found it in a box of family photos a couple of years after his death.

"This picture haunts Daddy," she told her mother.

"What do you mean?" Pat Hargrave asked.

Corinne pointed at the address spelled out in wrought iron on the top step: "Nine Eleven."

T.J. Hargrave was one of hundreds of New Jersey dads who went to work in the city on a gorgeous fall day 10 years ago and never came home. Their loss is a shared wound never far from the minds of the people who live in the bedroom communities of northern New Jersey.

The three Hargrave sisters -- Corinne, 18, Casey 16, and Amy, 14 -- had never shared their story with anyone outside their close circle of friends and the families they met at America's Camp, a Massachusetts retreat for kids who lost a close family member on 9/11. But they agreed to talk to Schuster, a Rutgers University student from their prosperous hometown of Readington Township, to keep the memories of their father from fading.

For the two oldest, Corinne and Casey, those memories come back in bits and pieces. Ten years later, it's hard to tell what's truly recalled and what's suggested by family stories, photos and home movies. Amy, who was just 4 when her father died, relies on her sisters for her memories.

Before she met the Hargraves, Schuster spent a semester learning everything she could about the terrorist attacks as one of 20 students enrolled in The Rutgers University 9/11 Project. She and her classmates were coached on how to question people who survive traumatic experiences. They read books about September 11 and listened to speakers, including former New Jersey Gov. Thomas Kean, who chaired the 9/11 Commission.

And then they were told to find someone's story to tell. It was harder than they'd imagined. Many of the children of 9/11 were reluctant to talk about it. Some dreaded the 10th anniversary and the repeated replays of the planes, the impacts, the fireballs and the collapsing towers.

"It was like ripping off a Band-Aid," recalls Sarah Morrison, a junior who talked to a young man whose dream of a college soccer scholarship in California vaporized when he lost his mother at 17.

Jennifer Lilonsky sensed the young man she interviewed was telling her what he thought she wanted to hear. She could feel the protective presence of his mother in the next room during their first interview at his house in Marlboro. Later, when she talked to him at his dorm room in Maryland, he was more animated, even if he seemed incredibly sad.

It was different at the Hargraves' house. Schuster arrived for lunch and stayed until dinner. Pat was engaged in the conversation, and the family's closeness and good humor was evident. Schuster told the sisters they could stop talking if they felt tired or emotionally upset. They never did.

"I got lucky," she says. Not only did the Hargrave sisters share their story without reservation, they taught her lessons in love, dignity and resilience.

"If I were have to have something terrible happen to me, I would want to live my life like the Hargraves did," she said. "You can pick up the pieces, and even though there are a couple of pieces missing, you can hold yourself together and not have something bad stop you from living your life. That doesn't mean you're going to forget. It's in your heart. It's not going to go away."

Untold stories

What was it like to lose a mother or father on 9/11? To grow up with a gaping hole in your heart? To be an emblem of one of the worst events in recent U.S. history?

Those are among the lingering questions of the tragedy because the stories of the children of September 11 have been so difficult to tell. Many resent the media for relentlessly bombarding them with the images of their parents' deaths. Kids who lose a parent to cancer or a car accident don't have to share it with the world, much less see it replayed over and over on television.

But would they open up to another member of the 9/11 generation? The current crop of college undergraduates was in middle school when the towers fell -- old enough to remember, young enough to relate as peers.

The Rutgers University 9/11 Project was born out of a brainstorming session by three members of the New Jersey Press Association. Why not use the association's charitable arm to fund a grant to train journalism students on narrative storytelling and compassionate interviewing techniques? They could get top journalism students at Rutgers to interview children from 9/11 families and create stories for New Jersey's media outlets to include in their anniversary coverage.

See one Rutgers student's video package about the 9/11 project

Rutgers, New Jersey's state university, seemed a natural fit. After all, the press association founded the university's journalism school in the 1920s.

With a $54,000 grant for cameras and other equipment, Rutgers professors Ron Miskoff and Liz Fuerst created a special course for the project. The reading list included texts on narrative storytelling and books on 9/11, including "The Ground Truth," by John Farmer, counsel to the 9/11 Commission, and "Your Father's Choice," by Daniel Zegart and Lyz Glick about the passengers on board United Flight 93, which crashed in a field in Pennsylvania. And of course, there was a field trip to ground zero.

To gain admission into the course, students wrote personal essays describing their experiences on September 11. Thirty students wrote essays, Miskoff said, and 20 of them made the cut, along with a handful of promising high school students.

Miskoff expected a dozen or so stories, based on his experiences with college students: "Two will have trouble with their boyfriends, one is going to get sick, one is going to drop out and decide college isn't for them."

He was pleasantly surprised: "Everybody came through."

Mary Fetchet, director of the family advocacy group Voices of September 11, coached the students to ask "open-ended questions" during the interviews and to just let their subjects talk. Some might cry, some might be angry, some might clam up, she cautioned.

For the Rutgers students, the project offered a chance to gain insight into the personal toll of the global and regional event that has dominated half their lives. For their subjects, it offered the opportunity to honor a loved one and share an intensely personal tragedy with a peer who also knows from witnessing the events of 9/11 how life can change in an instant.

For the rest of us, the 9/11 Project at Rutgers uncovered stories that have never before been fully told. They are being compiled on a website, and there is talk of a book. Already one or two have been picked up by hometown newspapers.

CNN talked with a dozen students and focused on five stories that capture different aspects of the 9/11 families' experiences. With the exception of the Hargraves, the other subjects were unavailable to talk, so their voices are shared through the students' work.

A paralyzing grief

For many of the Rutgers students and the 9/11 kids they interviewed, their stories began with a confusing morning in school. Adults suddenly seemed worried and scared, but they weren't talking. The children were left to speculate, and many concocted wild scenarios. They passed notes under their desks, trying to outdo each other. It was a time before smart phones and instant Internet access.

Whatever doomsday scenarios sprang from their childish imaginations, nothing could match the appalling truth, driven home for David Seamon when a fighter jet flew low overhead, shaking the building and setting off car alarms at his Catholic grade school in Somerset.

Seamon, now part of the Rutgers 9/11 project, went back to St. Matthias School to interview his former assistant principal before he talked to his subjects -- Marisa and Eddie Allegretto, a brother and sister from Colonia whose dad, Edward Sr., had worked as a bonds broker at Cantor Fitzgerald.

"I wanted to know what it was like to hold an umbrella over 800 kids," Seamon wrote in a class essay, "and why the school felt it was best to keep the kids in the dark about the tragedy. My questions painted a slightly accusatory picture, as I felt myself sticking up for my seventh-grade self. As if 10 years later, I still felt lied to."

Jean Patrick, now retired from her job as St. Matthias' assistant principal, told Seamon that teachers were under direct orders from the diocese not to tell younger students about the events unfolding that morning to avoid a panic. But the kids all knew something was up.

Eddie Allegretto was 11 and in sixth grade at another Catholic school, St. Cecilia's in Iselin. He was pulled out of class and sent home. All he'd been told was there'd been a plane crash. When he found the house filled with relatives in the middle of the afternoon on a weekday, he knew it was much more.

"At 11 years old, it doesn't process in your head that something bad happened," Eddie recalled. "But I walked in, I saw everyone here, I saw my mom. It just hit me."

His older sister Marisa watched the events unfold on TV in class at Bishop George Ahr High School in Edison. She was 14 and saw and heard enough to grasp the horror of what was happening. She caught a ride home with an older friend.

"Seeing the burning towers, the traumatized survivors, and the helpless jumpers was all too much," she told Seamon. "When I saw it on the TV, that's when I was not OK."

The loss of their father hit the Allegrettos so hard that they abandoned the pursuits they'd enjoyed with him. Marisa quit dancing, and Eddie quit sports, focusing instead on his grades. He felt the heavy burden of being the man of the family at 11.

"In the days, weeks and months that followed, grief acted as a glue that bound Eddie and Marisa to each other, their mother and their family," Seamon said. "Aspirations were put on hold, plans were canceled, and the family's faith was shaken."

Ten years later, they have returned to those passions of childhood. Marisa is teaching dance, and Eddie is studying to be a sportscaster. They are apprehensive about the anniversary, though, saying there's no cure for heartbreak. Time doesn't diminish the pain, they say. "It hits you more and more. It's always there," Marisa says.

"The most profound part about Eddie and Marisa's story is that despite the tragedy, the decade-long grieving process, and the prospect of a future without a father, they are OK," Seamon told CNN in an e-mail. "They smile, laugh and joke with each other. They finish each other's sentences. They have goals again, and the strength to achieve them."

He finds their strength daunting: "I could reach into the depths of my heart for solidarity and still come up short of the Allegrettos."

Read David Seamon's essay on the death of Osama bin Laden

Searching for a memory

No one softened the news for Sarah Morrison and her classmates when the towers fell.

"It was told to us straight," she recalls. The principal at Shalom Torah Academy, a small Jewish day school in Jamesburg, burst into her classroom and announced that planes operated by terrorists from the Middle East had hit the twin towers of the World Trade Center.

"We were 12, 13, and (the principal) looks at us and says, 'I just got off the phone with my mother, and my mother said she never thought she'd live through another Holocaust.' "

It is embedded in Jewish culture to confront terrorism and other atrocities, says Morrison, now a senior at Rutgers. You don't remain silent, and you don't hide the truth. It's a lesson learned through hard experience.

"The mentality is: If we don't stand up for ourselves, who is going to be there for us? When Jewish people need help, people don't sit idly by. We were instantly told, 'This is as serious as a Holocaust.' That's a pretty serious parallel to draw. I think it was appropriate at the time," Morrison says.

The young man she interviewed was 17 when his mother died.

Jean Depalma was a partner at Marsh & McLennan, which lost 295 employees on September 11. She and her husband had divorced the year before, and her oldest child, Drew, was exerting his independence and spending lots of time with his friends. As a result, he can't point to a final conversation or special day with his mother. She was just there one day, and gone the next. Her remains were never recovered, so there's no gravesite to visit, and he gets no sense of her presence at ground zero.

Her death plunged him into shock and depression. It took him a year to cry. People told him he was brave and stoic, but inside he was numb. He was an accomplished soccer player, and he and his mom were looking at colleges, particularly in California and South Carolina. The idea of going to college out of state appealed to him.

But then it all stopped.

"I got a lot of scholarships," he told Morrison. "I pretty much got a free ride. And I chose to go to Hoboken."

He studied engineering at Stevens College, staying in New Jersey because he couldn't tear himself away from his family after his mother died.

He deeply feels the void of not being able to recall those last memories or visit a place where he can feel connected to her. He looked into the sky one night, chose a star and gave it her name. He gazes at it often. A friend gave him an iron cross pried from a metal beam from the World Trade Center. He keeps it in a drawer.

"With people with cancer, you know they're dying, you spend more time with them," he told Morrison. "I'm not sure which is better: there are good days and randomly they're gone, or there's a bunch of bad days and you just hang out with them a little longer."

After struggling for years, Depalma is in a good place.

"Right after, I kind of just didn't do much. I was a big lump on a log," he told Morrison. "As time passed and I started to heal a little bit, I kind of felt that I had to make a good life for myself, because obviously, she wouldn't want me to sit around and mourn for her forever. I still think of her every day. I kind of tried to move on while keeping her in my heart."

He married his college sweetheart last year, and they are building a life together. He's working as an engineer and making plans for the future, not just "living paycheck to paycheck" like some of his friends.

He is training for a marathon, which he plans to run in his mother's honor in October.

The World Trade Center also was special place for his Rutgers interviewer, even if she didn't lose anyone there. Morrison's parents met at the top of one of the towers, broke up and reunited there before they were married. When the towers fell, it felt personal, but "we didn't see it as the end of our dreams," she said.

"This was a national tragedy, but people forget that something personal was lost there," she added. "There was a 17-year-old whose life was ripped out from underneath him because of September 11. I think that's lost on people."

The final score

Marlboro is the quintessential New Jersey bedroom community, and it lost 14 people on September 11. Jennifer Lilonsky grew up wondering about them, and she asked to interview Corbin Mayo because she wanted to get to know a 9/11 child from her hometown.

She is saddened by his struggle, by how he received so much public attention in the beginning but seemed so lost afterward.

Mayo doesn't remember much of sixth grade, or seventh grade for that matter. He went into a tailspin after his father, Robert Mayo, a deputy fire safety director for the World Trade Center, died on September 11. At first, he wouldn't believe it: He called his father's cell phone for weeks. And then Mayo's remains were found, and reality sank in.

His mother told Corbin she spoke with his dad after the first plane flew into the north tower and begged him to come home on the ferry. "I'll talk to you later," he told her before going back to help with the rescue effort. He was one of six fire safety directors who died that day.

The previous night, Corbin had been watching "Monday Night Football" with his dad. The New York Giants were in Denver playing the Broncos, and the first half was a seesaw battle. The Giants had fallen behind before coming back, but Corbin had to go to bed before the game ended. His dad left him a note on the kitchen table with the final score: "GIANTS = 20" and "BRONCOS = 31."

It was just a final score, but that last note written in his father's hand holds special significance now.

Mayo keeps it in a heart-shaped box along with other mementos of his dad. Because Robert Mayo died a hero, his son received plenty of media attention -- unlike the other 9/11 children interviewed by the Rutgers students. He was interviewed by Katie Couric on NBC's "Today" show, and when he said he dreamed of meeting Michael Jordan, the wish came true the next day.

The owner of the New York Giants saw his story in the local paper, and Mayo was invited to a game. He visited the luxury box and the locker room, posing for photos with his gridiron heroes -- Tiki Barber, Michael Strahan and others.

Corbin also visited the White House to receive his father's Medal of Valor.

But after the cameras went away, he struggled in school. He was angry and rebellious. He was prescribed anti-depressants in high school, he told Lilonsky. His mother battled breast cancer and remarried, but he didn't get along with his stepfather.

And then one day, he just decided to grow up. He went off the meds and struck up a civil relationship with his stepfather. He hunkered down with his studies and got into Towson University in Maryland. He joined a fraternity and finally feels more at ease. He's studying sports management, hoping to make a career out of a shared passion with his father.

"I know he's looking down on me, and I'm trying to make him proud as can be," he told Lilonsky. "I have an internship in the fall. I know he would be proud of me."

Lilonsky knows its only natural for people to want to help immediately after a tragedy. But Corbin Mayo's story taught her that the time to step up is in the long lonely days that follow that first outpouring of kindness.

When she interviewed him in Marlboro, the family's house was silent and felt empty, as if no one lived there. An uncollected package sat on the steps and a vacuum cleaner had been left in the center of the room. She says Mayo never really opened up to her.

"I just wanted to shake him," Lilonsky said. "Everybody expected sad stories with happy endings."

Still, the 9/11 project had a profound effect on her. It was a game changer. A former Manhattan chef, she took journalism classes in the hopes of becoming a food writer. Instead, she's chasing breaking news for the city's cable news channel.

"If it wasn't for this class," she said, "I'd be an intern for Martha Stewart and not NY 1."

Read Jennifer Lilonsky's story

A Walk for Dads

Travis Fedschun's 9/11 journey began on the afternoon of the attacks, when he accompanied his parents to the highest hilltop in his New Jersey hometown, Cedar Knolls, and stared at the black plume of smoke rising over the trees.

Ten years later, it would take him to Westfield, a posh suburb where the Walk for Dads, a train station memorial, pays tribute to 12 commuters who died on September 11.

He knelt before a concrete impression of footprints -- a woman's and two children's -- and wondered if they belonged to his interview subject, Kaila Starita, and her mother and brother.

Fedschun says he wanted to interview someone who hadn't told their story before to better understand 9/11 from a family's perspective.

"They are more than just numbers in stone, many were just average people just going about their day when they wound up in this situation," he says.

Kaila was just 6 when her father, Anthony Starita, died. He was 35, a senior partner at Cantor Fitzgerald, and worked on the 104th floor of the north tower.

"I thought this was only a time thing and that he would be back in only a week or so," she told Fedschun. "Since I was so little, I didn't understand what was going on."

The final leg of his journey took Fedschun to the backyard memorial the family built for Starita behind a massive white frame house on a tree-lined street not far from the center of town.

But 16-year-old Kaila Starita says she feels closest to her dad at ground zero. This year, she hopes to be among the 9/11 family members called on to read the names of the dead at the annual ceremony there. She says she won't watch the television footage of planes flying into the towers and that she'll never feel any closure.

During the last summer of his life, Anthony Starita was trying to spend less time at the place where his daughter now feels his presence most strongly. He was working on balancing his life, scaling back his work hours a bit and cutting back on the golf. The family had taken a vacation in Wildwood on the Jersey Shore that last summer.

On the night of September 10, he got to spend some extra time with Kaila and her brother, who was 3. Their mother had gone to a long PTA meeting, and they spent the evening watching television. Kaila smiles as she remembers how he tucked her into bed that night -- one of her last memories of her father.

She's grateful for that last summer together at the beach. Many of the pictures used on his missing person flyer in the days after 9/11 were taken during that vacation. This summer, the family ventured back to Wildwood for the first time as they prepared for the 10th anniversary of his death.

Fedschun was startled recently as he watched a film clip about 9/11 at the Newseum in Washington. It featured a makeshift clearing house of missing persons that sprung up at ground zero in the tense days following the attacks.

His heart jumped when the camera focused on a crying woman holding up one of the posters. It was Anthony Starita's.

Because of the project, Fedschun said, "I now know he was an avid golfer, could probably fill an entire room with his tie collection and would spend extra time out in the yard watching his kids play. I think that's a much better understanding than simply reading (about 9/11) from a textbook."

'You are going to grow up to be good people'

"That's for me!" Megan Schuster thought the minute she saw a journalism class on September 11 being offered. She immediately got to work on the essay that would win her admission into the course.

Surrounded by chaos in her sixth grade class, she'd taken comfort in her routine. After all, her peanut butter sandwich that day still tasted like any other, even if her teachers were whispering in clusters and looked worried.

"I remember crying and seeing other students around me crying," she wrote about the dark days immediately after the attacks. Her mother, Geri, says she didn't notice any change in Megan's behavior but recalls constantly crying and watching television with her children.

"It probably left an impression in her mind that something was seriously wrong," Geri Schuster said of the oldest of her four children. "It's almost as if 9/11 made the children lose their innocence. ... They saw then that not everything was good in the world."

The tragedy hit home when they learned about T.J. Hargrave's death.

"I remember going home and learning that the husband of one of my mom's friends had died in the attack," Megan Schuster said. "She had three children and now was unexpectedly a single mother."

She thought about the Hargraves often over the years and decided to interview them for her project. Pat Hargrave agreed, saying it would be good for her girls to share memories of their father on the 10th anniversary of his death.

The Hargraves met with Schuster and CNN in Pickell Park in Readington, where a small memorial stands in remembrance of T.J. Hargrave and the township's other 9/11 victim.

Pat Hargrave wasn't thinking about fate or foreshadowing when she took the picture Corinne would later find, the one she said haunts her father. But Pat remembers the day vividly. She and T were dating back then. They weren't a family yet, and their whole lives lay ahead of them.

They'd gone to Wildwood, but it was a lousy beach day at the Jersey Shore so they headed to nearby Cape May. He was frozen in time as he sat down on the steps of one of the rambling Victorians, the "painted ladies" that make Cape May a popular honeymoon destination. She kept the photo because she thought he was so good looking.

Hargrave was an actor as a child, appearing in commercials for Sealtest ice cream. He was the boy in the yellow rain coat in Morton salt commercials that promised, "When it rains, it pours." His speaking line was, "It really works!" Later he had a role in a TV movie, "The Prince of Central Park," and a recurring role on the soap "The Guiding Light." When he left the show, his role of T.J. Werner went to an up-and-coming young actor named Kevin Bacon.

His friends compared him to a walking Zagat's guide; he always knew when a hot new restaurant was opening. Although he never finished college, Hargrave rose through the ranks at Cantor Fitzgerald. One of his projects was eSpeed, the online bond-trading program that helped the company stay afloat in the dark days after September 11.

"There are so many 'what ifs' in this story," Schuster said. "T.J. had a desk mate, and ever since the 1993 bombing (at the World Trade Center), Cantor Fitzgerald required employees to personally greet visitors in the lobby. T.J. and his desk mate worked on the 105th floor and took turns. On 9/11, it was the desk mate's turn to greet the visitor and T.J. stayed behind. He died. The desk mate survived."

When he called home for the last time, he told Pat something terrible has happened, and they were running out of air. He said he loved them. When Pat frantically tried for the next 24 hours to call him back on cell phone, she couldn't get through.

He lived a big life full of family, and even now there are photographs of him all over the house, Schuster says. Adds Pat, "I wouldn't say it's a sad house. It's a loud house."

Although Pat Hargrave was devastated, she held herself together for the sake of her daughters, who were 4, 6, and 8 when their father died. She tells them losing him on 9/11 is just a part of their story, not all of it.

"Here's the deal," she told them. "You are going to grow up to be good people, and that's all there is to it."

Corinne, now 18, remembers coming home from school after the attacks to find the house filled with relatives and food. So many people brought hams and cakes and lasagna they had to invest in a second freezer.

"When people don't know what to do, they make food," she told Schuster.

Every Wednesday night, an uncle came over and read them a story and tucked them into bed. It gave their mother time to cope with her own grief.

First responders form 'cancer club'

First responders form 'cancer club'

How has your life been since 9/11?

How has your life been since 9/11?

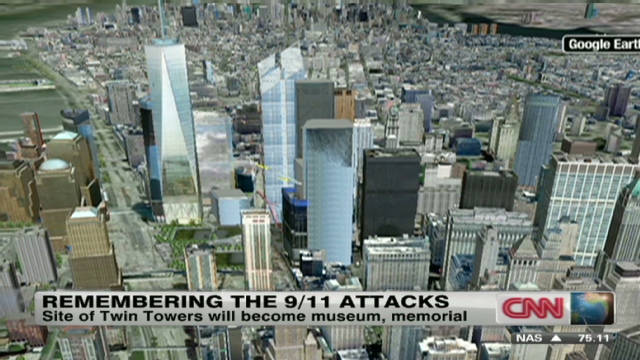

New York's changing skyline

New York's changing skyline

Believing in rebuilding ground zero

Believing in rebuilding ground zero

Casey, now 16, remembers seeing her mother cry just once -- at their father's memorial service. Until then, Casey kept expecting him to walk through the door at any time.

Amy, now 14, remembers spending a lot of time alone in her room, not quite sure what was going on. She believes her father watches down on her from heaven.

If that's the case, her mother asks, "Then why do you do some of the things you do?" Amy smiles and says she hopes he's looking at one of her sisters during her less-than-stellar moments.

The girls just want to blend in. When she was in the fourth grade, Corinne came home in tears, her mother recalled. Somebody introducing a new student around school announced, "That's Cori, and her father was killed on September 11."

Her mother advised her then, as she often does: "That's not who you are. You're a piano player. You're a soccer player. You're a good student, and your father died on 9/11."

They don't like when the topic of 9/11 comes up in history class, and they don't like explaining themselves to strangers. For Cori and Casey, the transition to high school was difficult because everybody wanted to know their story. Their friends knew, and that was enough. They didn't want to be the 9/11 poster children.

Corinne begins college this month at New York University, just over a mile from where her father died. She feels comfortable in her father's favorite city. Casey already has been to England on a school trip and wants to see Spain and Greece next. Amy says she's still figuring it out.

They want to lead lives that would make their father proud. Like Kaila Starita, Amy is thinking about reading from the list of the dead during this year's 9/11 remembrance.

Schuster says she plans to keep in touch with the Hargraves. They inspire her.

"When I was 11, I didn't think there was a worry in the world," she wrote. "Yes, I knew there were things like cancer and diseases that could take the ones I love. I knew that there were murders and crazy people out there. I learned about Hitler and Pearl Harbor and all the things of the past that negatively affected our country. But that's it -- they were in the past and they were far away from me."

The Hargraves taught her how to hold her head up and cope with tragedy, see the big picture and not let a single, horrific event define her life, Schuster says.

Theirs may be just one story among nearly 3,000 lives lost, but it's one that now feels like her story, too.